Strategic Stone Study: a Building Stone Atlas of the Isle of Wight

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 24 Autumn 2019

Quarr Abbey Issue 24 NEWSLETTER Autumn 2019 Unity of Life The man had just parked his bicycle and was taking off his helmet when, seeing me, he sort of abruptly asked: “Tell me, Father: What should I do so that Friends of Quarr what I do when I am praying in this amazing church and what I do outside The Friends are pleased to report that become one thing?” – “Good question”, I replied “How can our life be ‘one’?” the retiring collection from the Concert This question concerns all, but in a sense, it lies at the heart of monastic of Sacred Music, performed in the identity. The monk strives for unity. The Latin word monachus, which gave Abbey Church by the Orpheus Singers the English ‘monk’, comes from the Greek ‘monos’: ‘one’. The monks’ life in aid of our Accessible Paths Project, tends towards unity. They pursue it and already manifest it: a community at amounted to £712. The Gift Aid of £118 prayer is a sign of unity. will go to the abbey. It is not always easy, though. On the one hand, one has to consent to positive I would like to thank the Orpheus Singers on behalf of the Friends for tensions such as prayer and work; solitude and community; retreat and performing the concert and helping us hospitality. At first, they may be seen as tearing us apart. Well managed, they with our fundraising efforts in aid of this actually create a dynamic. The different poles of our lives begin to enrich one project. another. -

Planning and Infrastructure Services

PLANNING AND INFRASTRUCTURE SERVICES The following planning applications and appeals have been submitted to the Isle of Wight Council and can be viewed online https://www.iow.gov.uk/Residents/Environment-Planning-and-Waste/Planning/Planning-Development/Applic ation-search-view-and-comment using the link labelled ‘planning register’. Comments on the applications must be received within 21 days from the date of this press list, and comments for agricultural prior notification applications must be received within 7 days to ensure they be taken into account within the officer report. Comments on planning appeals must be received by the Planning Inspectorate within 5 weeks of the appeal start date (or 6 weeks in the case of an Enforcement Notice appeal). Details of how to comment on an appeal can be found (under the relevant LPA reference number) at https://www.iow.gov.uk/Residents/Environment-Planning-and-Waste/Planning/Planning-Development/Applic ation-search-view-and-comment For householder, advertisement consent or minor commercial (shop) applications, in the event of an appeal against a refusal of planning permission, representations made about the application will be sent to Planning Inspectorate, and there will be no further opportunity to comment at appeal stage. Should you wish to withdraw a representation made during such an application, it will be necessary to do so in writing within 4 weeks of the start of an appeal. All written representations relating to applications will be made available to view online. PLEASE NOTE THAT APPLICATIONS -

STENBURY FEDERATION Interim Executive Headteacher: Mr M Snow Chair of Governors: Mrs D Barker [email protected]

STENBURY FEDERATION Interim Executive Headteacher: Mr M Snow Chair of Governors: Mrs D Barker [email protected] Chillerton & Rookley Primary Godshill Primary Main Road, Chillerton School Road, Godshill Isle of Wight, PO30 3EP Isle of Wight, PO38 3HJ Tel. 01983 721207 Tel. 01983 840246 [email protected] [email protected] Wednesday 14th July 2021 Re: Godshill Class Structure for September 2021 Dear Parents and Carers, We are really looking forward to the end of term and a well-earned rest. Many of you will be wanting to know which classes and teachers your children will be having. The class structure for September will be: Class Class Name Teacher / Lead Support Staff Entrance to School Nursery Bembridge Windmill Marie Seaman Jim Palmer Nursery Gate Kate McKenzie Alana Monroe Reception Calbourne Mill Mrs Polly Smith Dawn Sargent Reception Gate – Lizzie Burden Car park Year 1/2 Osbourne House Miss Kirsty Hart Wendy Whitewood Main Entrance Year 2/3 The Needles Mr Conner Knight Lisa Young Main Entrance Brogan Bodman Year 4/5 Carisbrooke Castle Mrs Westhorpe and Jodie Wendes Car park side Mrs Tombleson entrance Year 5 Yarmouth Castle Mr Tim Smith Chantelle De’ath Steps side of school Lauren Shaw-Yates Year 6 St Catherine’s Mrs Boakes Danny Chapman Steps side of school Oratory Any pupils that are in the mixed class of Year 1/2 or 4/5 that are in Year 2 or 5 will be contacted individually by the school. School will start at 8:45am for all pupils. School finishes for all pupils at 3:00pm, except for Reception, who will finish at 2:55pm. -

I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE I provided by NERC Open Research Archive I BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY I MARINE REPORT SERIES TECHNICAL REPORT WB/95/35 I I I I I I BGS TECHNICAL REPORT WB/95/35 The Wight 1:250 OOO-scale Solid Geology sheet I (2nd Edition) by I I J Andrews I' I Geographical index Wight, English Channel I Subject index: Solid Geology I Production of report was funded by: Science budget I Bibliographic reference: Andrews, U. 1995. The Wight 1:250 OOO-scale Solid Geology sheet (2nd Edition) I British Geological Survey Technical Report WB/95/35 British Geological Survey Tel: 0131 667 1000 I Marine Geology & Operations Group Fax: 0131 6684140 Murchison House Tlx: 727343 West Mains Road I Edinburgh EH93LA I NERC Copyright 1995 I This report has been generated from a scanned image of the document with any blank pages removed at the scanning stage. Please be aware that the pagination and scales of diagrams or maps in the resulting report may not appear as in the original I I CONTENTS Page I' 1. INTRODUCTION 1 I 2. DATASET 2 'II 2.1 Onshore 2 2.2 Offshore 4 I 3. MAP REVISION 9 I 3.1 Amendments 9 3.2 Additional features 10 I 4. GEOLOGY 13 4.1 Structural history of the Wessex-Channel Basin 13 I 4.2 Stratigraphy 14 I 5. HYDROCARBONS 23 I 6. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 24 'I 7. REFERENCES AND SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY 25 I FIGURES I Figure 1 Location of the GSI deep-seismic survey used during map production I Permo-Triassic isopach map Figure 2 I I I I I I I I I 1. -

Selfbuild Register Extract

Address 4 When Ready Adults Children Individual Property Size Parishes Date Added Beds 1 - 2 years 2 0 3 bedroom property Bembridge | East Cowes | Nettlestone and Seaview 22/02/2018 Dorset within 1 year 2 0 2 bedroom property Sandown | Shanklin | Ventnor 13/04/2016 1 - 2 years 2 0 2 bedroom property Nettlestone and Seaview | Ryde | St Helens 21/04/2016 Isle of Wight 3 - 5 years 0 0 3 bedroom property Freshwater | Gurnard | Totland 22/04/2016 within 1 year 2 0 3 bedroom property Brighstone | Freshwater | Niton and Whitwell 08/04/2016 Isle Of Wight within 1 year 3 0 2 bedroom property Ryde | Sandown | St Helens 21/04/2016 Leicestershire 1 - 2 years 2 0 2 bedroom property Bembridge | Freshwater | St Helens 20/03/2017 Leics within 1 year 2 0 3 bedroom property Brighstone | Totland | Yarmouth 20/03/2017 1 - 2 years 5 0 4 bedroom property Cowes | Gurnard 15/08/2016 London within 1 year 2 0 3 bedroom property Bembridge | Ryde | St Helens 07/08/2018 London within 1 year 2 0 4 bedroom property Ryde | Shanklin | Ventnor 13/03/2017 Isle Of Wight 1 - 2 years 2 0 2 bedroom property Chale | Freshwater | Totland 08/04/2016 Isle Of Wight within 1 year 2 0 3 bedroom property East Cowes | Newport | Wroxall 22/04/2016 Isle Of Wight 1 - 2 years 2 0 2 bedroom property Freshwater | Shalfleet | Yarmouth 10/02/2017 Isle Of Wight within 1 year 2 0 3 bedroom property Gurnard | Newport | Northwood 11/04/2016 Isle of Wight within 1 year 2 0 3 bedroom property Fishbourne | Havenstreet and Ashey | Wootton 22/04/2016 Isle Of Wight within 1 year 3 0 3 bedroom property -

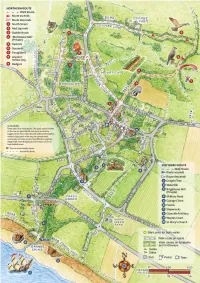

Brighstone Map Leaflet Update Layout 1

the countryside with respect. with countryside the treat please and footwear and © Paul Bradley © Paul clothing protective suitably Wear slippery. become can details given. Please take care when walking as footpaths footpaths as walking when care take Please given. details the in changes for or omissions, or errors for responsibility Whilst every care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of this information, we cannot accept accept cannot we information, this of accuracy the ensure to taken been has care every Whilst Disclaimer: about current times and routes. and times current about for up-to-date information up-to-date for www.islandbuses.info Please check the Southern Vectis timetable at timetable Vectis Southern the check Please Brighstone - Freshwater - Totland. - Freshwater - Brighstone from Bus Station in Newport - Shorwell - Shorwell - Newport in Station Bus from Route 12 Route Bus Route Bus amenities please go to to go please amenities www.brighstoneparish.org For more information about local accommodation and accommodation local about information more For 01983 740844 01983 Dinosaur Expeditions. March - Oct - March Expeditions. Dinosaur 01983 740291 01983 Thorncross Fishing Lake Fishing Thorncross 01983 741302 01983 Mottistone Manor Gardens & NT Shop NT & Gardens Manor Mottistone 01983 741484 01983 High Adventure Paragliding Adventure High 01983 740941 01983 Island Fish Farm & Fishing Lakes Fishing & Farm Fish Island 01983 740352 01983 Isle of Wight Pearl Wight of Isle 01983 741560 01983 Mottistone Farm Shop Farm Mottistone -

Schedule 2019 24/06/19 2 23/12/19 OFF

Mobile Library Service Weeks 2019 Mobile Mobile Let the Library come Library Library w / b Week w / b Week Jan 01/01/19 HLS July 01/07/19 HLS to you! 07/01/19 HLS 08/07/19 HLS 14/01/9 1 15/07/19 1 21/01/19 2 22/07/19 2 28/01/19 HLS 29/07/19 HLS Feb 04/02/19 HLS Aug 05/08/19 HLS 11/02/19 1 12/08/19 1 18/02/19 2 19/08/19 2 25/02/19 HLS 26/08/19* HLS Mar 04/03/19 HLS Sept 02/09/19 HLS 11/03/19 1 09/09/19 1 18/03/19 2 16/09/19 2 25/03/19 HLS 23/09/19 OFF April 01/04/19 HLS 30/09/19 HLS 08/04/19 1 Oct 07/10/19 15/04/19 2 14/10/19 22/04/19 OFF 21/10/19 29/04/19 HLS 28/10/19 May 06/05/19* HLS Nov 04/11/19 13/05/19 1 11/11/19 20/05/19 2 18/11/19 OFF 27/05/19* OFF 25/11/19 June 03/06/19 HLS Dec 02/12/19 10/06/19 1 09/12/19 17/06/19 HLS 16/12/19 Schedule 2019 24/06/19 2 23/12/19 OFF 06/05/19—May Day Bank Holiday 27/05/19—Whitsun Bank Holiday 26/08/19—August Bank Holiday The Home Library Service (HLS) operates on weeks when the Mobile Library is not on the road. -

Little Budbridge, Budbridge Lane, Merstone, Isle Of

m LITTLE BUDBRIDGE, BUDBRIDGE LANE, MERSTONE, ISLE OF WIGHT PO30 3DH GUIDE PRICE £1,545,000 A beautifully restored, 5 bedroom period country house, occupying grounds about 7.5 acres in a quiet yet accessible rural location. Restored to an exceptional standard, this small manor house is constructed largely of local stone elevations beneath hand-made clay peg tiled roofs. It is Grade II listed with origins in the 13th Century, and with a date stone from 1731. Included are the neighbouring barns and outbuildings which have consent for several holiday letting units. After a period of gentle decline the property was virtually derelict in 2013 and in 2013-15 it underwent a programme of complete renovation, extension, improvement and under the supervision of the conservation team of the Local Authority. Modern high-quality kitchen and bathroom fittings by 'Porcelanosa' have been installed to sympathetically compliment the many original period features. The finest original materials and craftsman techniques have been used and finished to a high standard. The house enjoys an elevated position within about 7.5 acres of grounds with extensive vistas across the beautiful surrounding countryside of the Arreton Valley to downland beyond. The gardens have been terraced, landscaped and enclosed in new traditional wrought-iron parkland fencing, with matching entrance gates, beyond which are lakes and a grass tennis court. The property is set beside a quiet "no through" lane within a picturesque rural location, yet is easily accessible to Newport, (4 miles) with mainland ferry links to Portsmouth 6.5 miles away at Fishbourne. Ryde School is also easily accessible about 8 miles away. -

Bonchurch to Ventnor: Going in Hard!

THE COASTAL TRAIL - VENTNOR & BONCHURCH - KS5 Bonchurch to Ventnor: Going in hard! Welcome to Ventnor! In this location, you will study: ü The Shoreline Management Plan for this location ü The coastal management strategies in place in this location. Introducing the SMP A SMP is a document which is produced for all areas along the coastline in England and Wales. Each of the 11 sediment cells around this coastline are divided into sub-cells (based on knowledge of local processes) and, for each of these, an SMP is written. It examines the risks associated with coastal processes (erosion/fooding) and presents a policy detailing an approach to managing those risks. There are four possible options: ‘hold the line’, ‘advance the line’, ‘managed retreat/realignment’, or ‘do nothing’. Discuss with a partner, and your teacher, what each of these policies mean. The policy between Bonchurch and Ventnor, on the south coast of the Isle of Wight, is to ‘hold the line’. This involves a multi-engineered approach using a variety of hard engineering strategies to retain the existing coastline. There are many reasons for this strategy in this location. Why the need? The area lies within a stretch known as the ‘Undercliff’; an area of complicated and ununiformed geology that is prone to landslides. There are a range of landslide features including rotational slumping, mudslides and rockfalls (pictured). Heavy rainfall and storms exacerbate the unstable conditions in the area. This stretch of coast is also vulnerable to wave attack due to a variety of reasons: » its large fetch across the Channel/Atlantic, its exposure to the south-west prevailing winds and resulting high energy waves and storm surges (over 1m above predicted levels); » sediment supply is limited and beaches are non-existent or very narrow, providing little natural protection at the base of the cliffs; » high energy destructive storm waves abrade the base of the cliffs and sea defences with gravel. -

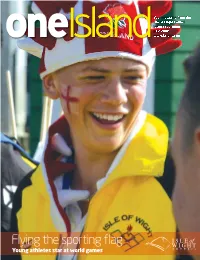

Flying the Sporting Flag

Your magazine from the Isle of Wight Council Issue seventeen July 2008 LKB'PI>KAwww.iwight.com Flying the sporting fl ag Young athletes star at world games Your magazine from the Isle of Wight Council Issue seventeen LKB July 2008 One Island is published each month, except for September and January – 'PI>KAwww.iwight.com 5BI@LJB these editions are combined with those of the previous month. If you have community news to share with other readers or would like to advertise in One Island, we would like to hear from you. We also welcome your letters – you can contact us by post, email or telephone. Post One Island, Communications, County Hall, Newport PO30 1UD Email [email protected] Telephone 823105 Flying the sporting flag Young athletes star at world games J>HFKD@LKQ>@Q @LRK@FIJBBQFKDP USEFUL CONTACTS Isle of Wight Council, County Hall, Unless otherwise stated, all meetings Newport PO30 1UD are in public at County Hall. Call Fax 823333 823200 24-hours before a meeting to Email [email protected] ensure it is going ahead and to check if Welcome to the July issue of Website www.iwight.com any items are likely to be held in private the council’s magazine, which session. this month celebrates the TELEPHONE SERVICES achievements of our young Council Call centre 821000 sportsmen and women at the FACE TO (council chamber) Mon to Fri: 8am to 6pm recent Youth World Island Saturday: 9am to 1pm FACE SERVICES 16 July (6pm) Games in Guadeloupe. For telephone assistance we Newport Help Centre Cabinet recommend you contact the call 29 July (6pm) Wroxall Community Centre Th ey proudly fl ew the Island’s centre directly where we aim to Tel 821000 19 August (6pm) venue to be confi rmed sporting fl ag at the games and answer as many enquiries as possible County Hall, Newport PO30 1UD many, no doubt, will be playing at this fi rst point of contact. -

Scheme of Polling Districts As of June 2019

Isle of Wight Council – Scheme of Polling Districts as of June 2019 Polling Polling District Polling Station District(s) Name A1 Arreton Arreton Community Centre, Main Road, Arreton A2 Newchurch All Saints Church Hall, High Street, Newchurch A3 Apse Heath All Saints Church Hall, High Street, Newchurch AA Ryde North West All Saints Church Hall, West Street, Ryde B1 Binstead Binstead Methodist Schoolroom, Chapel Road, Binstead B2 Fishbourne Royal Victoria Yacht Club, 91 Fishbourne Lane BB1 Ryde South #1 5th Ryde Scout Hall, St Johns Annexe, St Johns Road, Ryde BB2 Ryde South #2 Ryde Fire Station, Nicholson Road C1 Brading Brading Town Hall, The Bull Ring, High Street C2 St. Helens St Helens Community Centre, Guildford Road, St. Helens C3 Bembridge North Bembridge Village Hall, High Street, Bembridge C4 Bembridge South Bembridge Methodist Church Hall, Foreland Road, Bembridge CC1 Ryde West#1 The Sherbourne Centre, Sherbourne Avenue CC2 Ryde West#2 Ryde Heritage Centre, Ryde Cemetery, West Street D1 Carisbrooke Carisbrooke Church Hall, Carisbrooke High Street, Carisbrooke Carisbrooke and Gunville Methodist Schoolroom, Gunville Road, D2 Gunville Gunville DD1 Sandown North #1 The Annexe, St Johns Church, St. Johns Road Sandown North #2 - DD2 Yaverland Sailing & Boating Club, Yaverland Road, Sandown Yaverland E1 Brighstone Wilberforce Hall, North Street, Brighstone E2, E3 Brook & Mottistone Seely Hall, Brook E4 Shorwell Shorwell Parish Hall, Russell Road, Shorwell E5 Gatcombe Chillerton Village Hall, Chillerton, Newport E6 Rookley Rookley Village -

WALKING EXPERIENCES: TOP of the WIGHT Experience Sustainable Transport

BE A WALKING EXPERIENCES: TOP OF THE WIGHT Experience sustainable transport Portsmouth To Southampton s y s rr Southsea Fe y Cowe rr Cowe Fe East on - ssenger on - Pa / e assenger l ampt P c h hi Southampt Ve out S THE EGYPT POINT OLD CASTLE POINT e ft SOLENT yd R GURNARD BAY Cowes e 5 East Cowes y Gurnard 3 3 2 rr tsmouth - B OSBORNE BAY ishbournFe de r Lymington F enger Hovercra Ry y s nger Po rr as sse Fe P rtsmouth/Pa - Po e hicl Ve rtsmouth - ssenger Po Rew Street Pa T THORNESS AS BAY CO RIVE E RYDE AG K R E PIER HEAD ERIT M E Whippingham E H RYDE DINA N C R Ve L Northwood O ESPLANADE A 3 0 2 1 ymington - TT PUCKPOOL hic NEWTOWN BAY OO POINT W Fishbourne l Marks A 3 e /P Corner T 0 DODNOR a 2 0 A 3 0 5 4 Ryde ssenger AS CREEK & DICKSONS Binstead Ya CO Quarr Hill RYDE COPSE ST JOHN’S ROAD rmouth Wootton Spring Vale G E R CLA ME RK I N Bridge TA IVE HERSEY RESERVE, Fe R Seaview LAKE WOOTTON SEAVIEW DUVER rr ERI Porcheld FIRESTONE y H SEAGR OVE BAY OWN Wootton COPSE Hamstead PARKHURST Common WT FOREST NE Newtown Parkhurst Nettlestone P SMALLBROOK B 4 3 3 JUNCTION PRIORY BAY NINGWOOD 0 SCONCE BRIDDLESFORD Havenstreet COMMON P COPSES POINT SWANPOND N ODE’S POINT BOULDNOR Cranmore Newtown deserted HAVENSTREET COPSE P COPSE Medieval village P P A 3 0 5 4 Norton Bouldnor Ashey A St Helens P Yarmouth Shaleet 3 BEMBRIDGE Cli End 0 Ningwood Newport IL 5 A 5 POINT R TR LL B 3 3 3 0 YA ASHEY E A 3 0 5 4Norton W Thorley Thorley Street Carisbrooke SHIDE N Green MILL COPSE NU CHALK PIT B 3 3 9 COL WELL BAY FRES R Bembridge B 3 4 0 R I V E R 0 1