A Quiver Full of Mommy Blogs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

One and Only

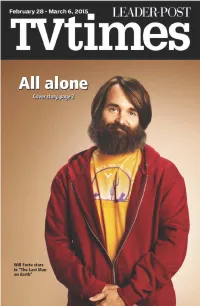

Cover Story One and only Fox tackles the loneliest number in ‘The Last Man on Earth’ By Cassie Dresch people after a virus takes out him get into a lot of really silly TV Media all of Earth’s population. His shenanigans. family is gone, his coworkers “It’s all just kind of stupid ello? Hi? Anybody out are gone, the president is gone. stuff that I go around and do,” Hthere? Of course there is, Everyone. Gone. he said in an interview with otherwise life would be very, So what does he do? He “Entertainment Weekly.” very, very lonely. Fox is taking a travels the United States doing “That’s been one of the most stab at the ultimate life of lone- things he never would have fun parts of the job. About once liness in the new half-hour been able to do otherwise — a week I get to do something comedy “The Last Man on sing the national anthem at that seems like it’d be amaz- Earth,” premiering Sunday, Dodger Stadium, smear gooey ingly fun to do: shoot a flame March 1. peanut butter all over a price- thrower at a bunch of wigs, The premise around “Last less piece of art ... then walk have a steamroller steamroll Man” is a simple one, albeit a away with it, break things. The over a case of beer. Just dumb little strange. An average, un- show, according to creator and stuff like that, which pretty assuming man is on the hunt star Will Forte (“Saturday Night much is all it takes to make me for any signs of other living Live,” “Nebraska,” 2013), sees happy.” Registration $25.00 online: www.skseniorsmechanism.ca or phone 306-359-9956 2 Cover Story Flame throwers and steam- ally proud of what has come rollers? Again, it’s a strange out of it so far.” concept, but Fox is really be- Of course, you have to won- Index hind the show. -

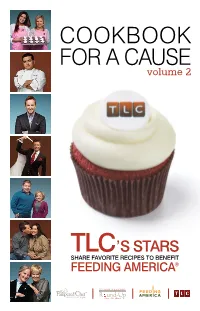

COOKBOOK for a CAUSE Volume 2

COOKBOOK FOR A CAUSE volume 2 TLC’S STARS SHARE FAVORITE RECIPES TO BENEFIT FEEDING AMERICA® FIGHTING HUNGER IN AMERICA ONE COOKBOOK at A TIME. The Pampered Chef® Cookbook for a Cause, Volume 2 benefits Feeding America®, the nation’s largest domestic hunger-relief organization. This year, the popular television network TLC® joined our mission to help fight hunger. TLC® stars from Cake Boss, Say Yes to the Dress, DC Cupcakes, The Little Couple, 19 Kids and Counting, What Not To Wear, and more, generously contributed their favorite recipes, in their own words. For each cookbook sold, we’ll donate $1 to Feeding America® to help provide eight meals to those in need.* We hope you’ll enjoy these recipes from the TLC® stars and the helpful tips and techniques from the experts in The Pampered Chef® Test Kitchens. As you gather around the table with family and friends, you can feel good that you’re helping another family in need to do the same. The Pampered Chef® The Pampered Chef® is the largest direct seller of everything you need to cook and entertain at home. At in-home Cooking Shows, guests see and try products, prepare and sample recipes, and learn quick and easy food preparation techniques and tips on how to entertain with style and ease — transforming the everyday into the extraordinary. TLC® is all about real-life reality, transporting the viewers into the lives of real-life extraordinary people with character. TLC® programs are entertaining, unfiltered and always reveal something worthwhile. TLC® is curious about people and finding the extraordinary in the everyday. -

Quackenbushfamil00andr.Pdf

i -X-' ^^. ,. •-'° *^ A^ »' ,'V' *'^l^^ • . s /> <r^ "-^^0^ 1/. ^>* <*D' ^^-V ^. ^0^ ° o . » * ,G o 'o ^ ^^ . .G^ ^^ • • • . ^ v* , ^_ ri> \.T The Quackenbush Family N HOLLAND AND AMERICA Compiled by Adriana Suydam Ouackexbush (1 1 50) Published by yuaekenbush & Co. Palerson, N. J. 190» ^.•?'" CONTENTS. Preface 5 The Family in Holland 7 The Village of Oestgeest 16 The Coat of Arms 19 The Family in America 20 First Generation 23 Second Generation 27 Third Generation 37 Fourth Generation 48 Fifth Generation 71 Sixth Generation 98 Seventh Generation 119 Eighth Generation 163 Ninth Generation 184 Tenth Generation 193 Eleventh Generation 194 Appendix 195 Index 201 l^vtfntt. N compiling the present history, two brief works on the same subject, viz : the Quackenbush chapter in " Talcott's New York and New England Families," ** and Richard Wynkoop's Genealogical Notes on the Quacken- bos Family," have been taken as a basis, subject to such cor- rections as were deemed necessary in the light of recent re- search. The lineages as traced by these Vv^riters have been considerably developed, how^ever, by the addition of everything obtainable concerning individual members of the Quackenbush or Quackenbos family, and in almost every case the baptismal and marriage records have been verified by comparison with accurate transcriptions of the several church registers. Mili- tary and naval records, obtained from official sources, have been inserted in the text, as well as numerous traditions, taken from local histories or communicated by descendants of the principals, but there has been no attempt at systematic bio- graphical notices except in the cases of professional men. -

06 4-15-14 TV Guide.Indd

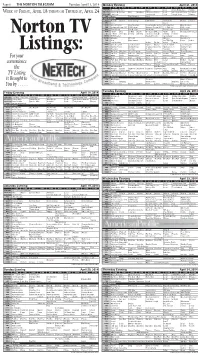

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, April 15, 2014 Monday Evening April 21, 2014 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Dancing With Stars Castle Local Jimmy Kimmel Live Nightline WEEK OF FRIDAY, APRIL 18 THROUGH THURSDAY, APRIL 24 KBSH/CBS 2 Broke G Friends Mike Big Bang NCIS: Los Angeles Local Late Show Letterman Ferguson KSNK/NBC The Voice The Blacklist Local Tonight Show Meyers FOX Bones The Following Local Cable Channels A&E Duck D. Duck D. Duck Dynasty Bates Motel Bates Motel Duck D. Duck D. AMC Jaws Jaws 2 ANIM River Monsters River Monsters Rocky Bounty Hunters River Monsters River Monsters CNN Anderson Cooper 360 CNN Tonight Anderson Cooper 360 E. B. OutFront CNN Tonight DISC Fast N' Loud Fast N' Loud Car Hoards Fast N' Loud Car Hoards DISN I Didn't Dog Liv-Mad. Austin Good Luck Win, Lose Austin Dog Good Luck Good Luck E! E! News The Fabul Chrisley Chrisley Secret Societies Of Chelsea E! News Norton TV ESPN MLB Baseball Baseball Tonight SportsCenter Olbermann ESPN2 NFL Live 30 for 30 NFL Live SportsCenter FAM Hop Who Framed The 700 Club Prince Prince FX Step Brothers Archer Archer Archer Tomcats HGTV Love It or List It Love It or List It Hunters Hunters Love It or List It Love It or List It HIST Swamp People Swamp People Down East Dickering America's Book Swamp People LIFE Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Listings: MTV Girl Code Girl Code 16 and Pregnant 16 and Pregnant House of Food 16 and Pregnant NICK Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Friends Friends Friends SCI Metal Metal Warehouse 13 Warehouse 13 Warehouse 13 Metal Metal For your SPIKE Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Jail Jail TBS Fam. -

By Jennifer M. Fogel a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

A MODERN FAMILY: THE PERFORMANCE OF “FAMILY” AND FAMILIALISM IN CONTEMPORARY TELEVISION SERIES by Jennifer M. Fogel A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Amanda D. Lotz, Chair Professor Susan J. Douglas Professor Regina Morantz-Sanchez Associate Professor Bambi L. Haggins, Arizona State University © Jennifer M. Fogel 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe my deepest gratitude to the members of my dissertation committee – Dr. Susan J. Douglas, Dr. Bambi L. Haggins, and Dr. Regina Morantz-Sanchez, who each contributed their time, expertise, encouragement, and comments throughout this entire process. These women who have mentored and guided me for a number of years have my utmost respect for the work they continue to contribute to our field. I owe my deepest gratitude to my advisor Dr. Amanda D. Lotz, who patiently refused to accept anything but my best work, motivated me to be a better teacher and academic, praised my successes, and will forever remain a friend and mentor. Without her constructive criticism, brainstorming sessions, and matching appreciation for good television, I would have been lost to the wolves of academia. One does not make a journey like this alone, and it would be remiss of me not to express my humble thanks to my parents and sister, without whom seven long and lonely years would not have passed by so quickly. They were both my inspiration and staunchest supporters. Without their tireless encouragement, laughter, and nurturing this dissertation would not have been possible. -

CHRISTIAN PATRIARCHY and the LIBERATION of EVE a Thesis

CHRISTIAN PATRIARCHY AND THE LIBERATION OF EVE A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of The School of Continuing Studies and of The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Studies By Jennifer Emily Sims, B.A. Georgetown University Washington, D.C. April 1, 2016 CHRISTIAN PATRIARCHY AND THE LIBERATION OF EVE Jennifer Emily Sims, B.A. MALS Mentor: Theresa Sanders, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Christian Patriarchy is a set of beliefs held by many conservative Christians that outlines gender roles based on a literal interpretation of scripture. These gender roles, also referred to as biblical manhood and biblical womanhood, dictate the hierarchy of authority where Christ is the head of the household, the husband is the head of the wife. Children are primed at a very young age to demonstrate the tenets of biblical manhood and biblical womanhood, but for young girls, their paths are strictly laid out for them to marry, birth many Godly children, and serve their husbands. The fundamentalist reading of Genesis 2-3 is used to justify female submission via Eve’s creation and subsequent role in the Fall of Humanity. This evangelical interpretation uses Genesis 2-3 as the foundational text to first justify women as subordinate based on creation order, and secondly justify women’s submission on Eve’s role in the Fall of Humanity. By using biblical interpretations to subordinate the woman’s position vis-à-vis her husband, women in these conservative Christian homes are locked into this role with little chance to follow a different path, and are often dependent on a dominant male figure for survival. -

The Quackenbush Family in Holland and America

i -X-' ^^. ,. •-'° *^ A^ »' ,'V' *'^l^^ • . s /> <r^ "-^^0^ 1/. ^>* <*D' ^^-V ^. ^0^ ° o . » * ,G o 'o ^ ^^ . .G^ ^^ • • • . ^ v* , ^_ ri> \.T The Quackenbush Family N HOLLAND AND AMERICA Compiled by Adriana Suydam Ouackexbush (1 1 50) Published by yuaekenbush & Co. Palerson, N. J. 190» ^.•?'" CONTENTS. Preface 5 The Family in Holland 7 The Village of Oestgeest 16 The Coat of Arms 19 The Family in America 20 First Generation 23 Second Generation 27 Third Generation 37 Fourth Generation 48 Fifth Generation 71 Sixth Generation 98 Seventh Generation 119 Eighth Generation 163 Ninth Generation 184 Tenth Generation 193 Eleventh Generation 194 Appendix 195 Index 201 l^vtfntt. N compiling the present history, two brief works on the same subject, viz : the Quackenbush chapter in " Talcott's New York and New England Families," ** and Richard Wynkoop's Genealogical Notes on the Quacken- bos Family," have been taken as a basis, subject to such cor- rections as were deemed necessary in the light of recent re- search. The lineages as traced by these Vv^riters have been considerably developed, how^ever, by the addition of everything obtainable concerning individual members of the Quackenbush or Quackenbos family, and in almost every case the baptismal and marriage records have been verified by comparison with accurate transcriptions of the several church registers. Mili- tary and naval records, obtained from official sources, have been inserted in the text, as well as numerous traditions, taken from local histories or communicated by descendants of the principals, but there has been no attempt at systematic bio- graphical notices except in the cases of professional men. -

P32 Layout 1

TUESDAY, JUNE 2, 2015 TV PROGRAMS 06:00 Lolirock 16:30 Home Fires 14:00 Perception 06:25 Hank Zipzer 17:25 The Widower 15:00 Glee 06:50 Girl Meets World 18:20 The Chase: Celebrity Special 16:00 Emmerdale 07:15 H2O: Just Add Water 19:10 Coronation Street 16:30 Coronation Street 07:40 Jessie 19:35 The Chase 17:00 The Ellen DeGeneres Show 00:20 Come Dine With Me 08:05 Wizards Of Waverly Place 20:30 Home Fires 18:00 Perception 01:10 MasterChef 08:30 Wizards Of Waverly Place 21:25 The Widower 19:00 Criminal Minds 02:00 Antiques Roadshow 08:55 Sabrina: Secrets Of A 22:20 Coronation Street 20:00 Bones 02:55 Come Dine With Me Teenage Witch 22:50 Emmerdale 21:00 Chicago Fire 03:20 Lorraine’s Fast, Fresh And 09:20 Sabrina: Secrets Of A 23:15 The Chase: Celebrity Special 22:00 The Americans Easy Food Teenage Witch 23:00 Mistresses 03:45 New Scandinavian Cooking 09:45 Austin & Ally 04:10 Antiques Roadshow 10:10 Austin & Ally 05:05 Masterchef: The 10:35 Wizards Of Waverly Place Professionals 11:00 Wizards Of Waverly Place 05:30 New Scandinavian Cooking 11:25 Jessie 00:20 Deadly Super Cat 05:55 Lorraine’s Fast, Fresh And 11:50 Jessie 01:10 The Living Edens Easy Food 12:15 Sabrina: Secrets Of A 02:00 Speed Kills 06:25 Come Dine With Me 02:50 Dangerous Encounters Teenage Witch 01:00 Good Morning America 06:50 Antiques Roadshow 12:40 Sabrina: Secrets Of A 03:45 Monster Fish 07:40 Come Dine With Me 04:40 How Big Can It Get 03:00 Better Call Saul Teenage Witch 04:00 Salem 08:05 Antiques Roadshow 13:05 Good Luck Charlie 05:35 Speed Kills 09:00 Ty Pennington’s Homes For 06:30 Dangerous Encounters 05:00 Good Morning America 13:30 Good Luck Charlie 07:00 Emmerdale The Brave 13:55 Dog With A Blog 07:25 Monster Fish 09:45 Come Dine With Me 08:20 The Lion Ranger 07:30 Coronation Street 14:20 H2O: Just Add Water 09:00 Suits 10:35 MasterChef 14:55 Lolirock 09:15 Unlikely Animal Friends 11:25 Antiques Roadshow 10:10 Dr. -

Lehigh Preserve Institutional Repository

Lehigh Preserve Institutional Repository Embracing Islam in the Age of Terror: Post 9/11 Representations of Islam and Muslims in the United States and Personal Stories of American Converts Brunet, Clemence 2013 Find more at https://preserve.lib.lehigh.edu/ This document is brought to you for free and open access by Lehigh Preserve. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of Lehigh Preserve. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Embracing Islam in the Age of Terror: Post 9/11 Representations of Islam and Muslims in the United States and Personal Stories of American Converts by Clemence Brunet A Thesis Presented to the Graduate and Research Committee of Lehigh University in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts in American Studies Lehigh University May 2013 i © 2013 Copyright Clemence Brunet ii Thesis is accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts in American Studies. Embracing Islam in the Age of Terror: Post 9/11 Representations of Islam and Muslims in the United States and Personal Stories of American Converts Clemence Brunet Date Approved Thesis Director Dr. Saladin Ambar Co-Director Dr. Bruce Whitehouse Department Chair Dr. Edward Whitley iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract 1 Introduction 2 Chapter One: Perceptions and Representations of Islam and Muslims after 9/11: language, media, hate groups and public opinion 8 Chapter Two: Muslim terrorists in the Entertainment Media and American Jihadists in the Media 49 Chapter Three: Personal Stories and Experiences of White American converts to Islam 85 Conclusion 133 Works Cited 138 Vita 155 iv ABSTRACT The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 were one of the most traumatic events experienced by the American people on their soil. -

The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015

The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015 Source: Nielsen, Live+7 data provided by FX Networks Research. 12/29/14-12/27/15. Original telecasts only. Excludes repeats, specials, movies, news, sports, programs with only one telecast, and Spanish language nets. Cable: Mon-Sun, 8-11P. Broadcast: Mon-Sat, 8-11P; Sun 7-11P. "<<" denotes below Nielsen minimum reporting standards based on P2+ Total U.S. Rating to the tenth (0.0). Important to Note: This list utilizes the TV Guide listing service to denote original telecasts (and exclude repeats and specials), and also line-items original series by the internal coding/titling provided to Nielsen by each network. Thus, if a network creates different "line items" to denote different seasons or different day/time periods of the same series within the calendar year, both entries are listed separately. The following provides examples of separate line items that we counted as one show: %(7 V%HLQJ0DU\-DQH%(,1*0$5<-$1(6DQG%(,1*0$5<-$1(6 1%& V7KH9RLFH92,&(DQG92,&(78( 1%& V7KH&DUPLFKDHO6KRZ&$50,&+$(/6+2:3DQG&$50,&+$(/6+2: Again, this is a function of how each network chooses to manage their schedule. Hence, we reference this as a list as opposed to a ranker. Based on our estimated manual count, the number of unique series are: 2015³1,415 primetime series (1,524 line items listed in the file). 2014³1,517 primetime series (1,729 line items). The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015 Source: Nielsen, Live+7 data provided by FX Networks Research. -

To Cover Our Daughters: a Modern Chastity Ritual in Evangelical America

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Religious Studies Theses Department of Religious Studies 2009 To Cover Our Daughters: A Modern Chastity Ritual in Evangelical America Holly Adams Phillips Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/rs_theses Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Phillips, Holly Adams, "To Cover Our Daughters: A Modern Chastity Ritual in Evangelical America." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2009. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/rs_theses/28 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Religious Studies at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religious Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TO COVER OUR DAUGHTERS: A MODERN CHASTITY RITUAL IN EVANGELICAL AMERICA by HOLLY ADAMS PHILLIPS Under the Direction of Kathryn McClymond ABSTRACT Over the last ten years, a newly created ritual called a Purity Ball has become increasingly popular in American evangelical communities. In much of the present literature, Purity Balls are assumed solely to address a daughter’s emerging sexuality in a ritual designed to counteract evolving American norms on sexuality; however, the ritual may carry additional latent sociological functions. While experienced explicitly by the individual participants as a celebration of father/daughter relationships and a means to address evolutionary -

Should Christians Use Birth Control?

STATEMENT DE-194 SHOULD CHRISTIANS USE BIRTH CONTROL? by H. Wayne House Summary Christian couples are pulled in different directions by people, movements, and circumstances on the issue of whether to have children. Some believe that no birth control should be used, whereas others maintain that a couple may properly choose never to have children at all. Most stand somewhere in the middle. The secular birth control movement glorifies small families while many Christians decry all use of conception-control devices or procedures. The Bible provides a balance. It exalts the bearing of children while recognizing that one’s duties in the world may limit the number of children borne or delay childbearing as husband and wife seek to fulfill the mandate of bei ng stewards over creation. The matter of birth control has been a concern of married couples for hundreds, if not thousands, of years. In recent times, with modern technology developing easier and more sophisticated methods of birth control, it has become commonplace in most Western nations for couples to use birth control (which includes conception control and abortion) to limit the size of their families. 1 Christians in all ages have generally practiced some form of birth control, whether through medica l devices or by more natural means, such as restricting intercourse to certain periods of the month or through coitus interruptus. Though the Roman Catholic church declared birth control a violation of natural law in the papal encyclical Humanae Vitae (1965), most Protestants have considered some forms of birth control morally acceptable. Recently, however, Mary Pride and other evangelical Christians have denounced such procedures as sinful.