Pennsylvania Bituminous Coal Production 1977-1997

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sublevel Retreat Mining in the Subarctic: a Case Study of the Diavik Diamond Mine

Caving 2018 – Y Potvin and J Jakubec (eds) © 2018 Australian Centre for Geomechanics, Perth, ISBN 978-0-9924810-9-4 doi:10.36487/ACG_rep/1815_02_Lewis Sublevel retreat mining in the subarctic: a case study of the Diavik Diamond Mine PA Lewis Rio Tinto, Canada LM Clark Rio Tinto, Canada SJ Rowles Rio Tinto, Canada CP Auld Rio Tinto, Canada CM Petryshen Rio Tinto, Canada AP Elderkin Rio Tinto, Canada Abstract Diavik Diamond Mine is located on the subarctic tundra of the Northwest Territories, Canada, 300 km northeast of Yellowknife. When its first two open pits were exhausted in 2012, it completed the full transition to underground mining. Three orebodies are currently being mined underground using two mining methods: blasthole open stoping and sublevel retreat (SLR). SLR was not an original method as described in the feasibility study. As the pits were mined, the underground project developed, and additional information became available. Over time, it became apparent that SLR would be the optimal method for two of the orebodies. A great deal has been learnt throughout development and operation of the SLR method at Diavik. This paper examines considerations for ventilation, production drilling and blasting, geotechnical concerns, and operational constraints for SLR mining in the subarctic. It also describes the process for method selection and the overall lessons learned. Keywords: sublevel retreat, SLR, arctic, underground 1 Introduction to Diavik The kimberlite orebodies of Diavik Diamond Mine were discovered in the early 1990s below Lac de Gras in the Northwest Territories of Canada. The mine is situated on the tundra of the Canadian subarctic on what is locally known as East Island. -

Douglas Simpson Archive

Douglas Simpson Archive Papers donated by Angela Simpson Papers dated December 1942 - September 1983 NEIMME/DS/1- NEIMME/ DS/81 NEIMME/DS/1 Creation Date: 1982/1983 Extent and Form: 1 A4 page-double sided-printed Scope and Content: Frontpiece Nos: 250-260- Black & White photograph of Douglas N Simpson BSc, CEng, FIMinE. President of the Institution of Mining Engineers 1983-1984 + a short biography of his career up un till 1967. NCB Papers/Reports NEIMME/DS/1/1a-e Creation Date: 11 August 1954 Extent and Form: 5 foolscap pages-typed Scope and Content: Coal Mines Act, 1911. The ministry of Fuel and Power in pursuance of Clause 14(3) of the Coal Mines (Explosives) Order, 1951, Hereby approves the type of ELECTRIC SHOT FIRING APPARATUS known as THE BEETHOVEN DYNAMO-CONDENSER TYPE MARK II 100 SHOT EXPLODER manufactured by THE WILKES BERGER ENGINEERING COMPANY LIMITED of High Wycombe, Bucks. And submitted by MARSTON EXCELSIOR LIMITED of Fordhouses, Wolverhampton designed, constructed and marked in accordance with the Schedule annexed hereto as an electrical shot-firing apparatus for use in sinking operations or in a part of a mine where permitted explosives are not required to be used. NEIMME/DS/1/2a-e Creation Date: [no date] Extent and Form: 5 foolscap pages-typed Scope and Content: CONTROL OF CAPITAL AND MAJOR REVENUE EXPENDITURE. (Incorporating discontinuance of Activities and disposal of assets) NEIMME/DS/1/3 Creation Date: [no date] Extent and Form: spreadsheet-typed Scope and Content: ITEMS AS SUPPLIED BY BOARD COMMON TO ALL CONTRACTS. 1. Temporary access roads etc. -

Technical Report for the Kensington Gold Mine, Juneau, Southeast Alaska, U.S.A

TECHNICAL REPORT FOR THE KENSINGTON GOLD MINE, JUNEAU, SOUTHEAST ALASKA, U.S.A. Prepared for Coeur Mining, Inc. NI 43-101 TECHNICAL REPORT – UPDATED PROJECT STUDY Effective Date: December 31, 2017 Report Date: April 25, 2018 Prepared by: Kyle Beebe, P.E., Coeur Alaska, Inc. Isaac Oduro, RM SME, MAusIMM (CP), Coeur Alaska, Inc. Raul Mondragon, RM SME, Coeur Mining, Inc. Kensington Mine Southeast Alaska, U.S.A. NI 43-101 Technical Report April 25, 2018 CAUTIONARY STATEMENT ON FORWARD-LOOKING INFORMATION This technical report (Report) contains forward-looking statements within the meaning of the United States (U.S.) Securities Act of 1933 and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 and the equivalent under Canadian securities laws that are intended to be covered by the safe harbor created by such sections. Such forward-looking statements include, without limitation, statements regarding Coeur Mining, Inc.’s (Coeur’s) expectations for the Kensington Gold Mine and its expansions, including estimated capital requirements, expected production, cash costs and rates of return; Mineral Reserve and Resource Estimates; estimates of gold grades; expected financial returns and costs; and other statements that are not historical facts. We have tried to identify these forward-looking statements by using words such as “may,” “might”, “will,” “expect,” “anticipate,” “believe,” “could,” “intend,” “plan,” “estimate”, and similar expressions. Forward- looking statements address activities, events, or developments that Coeur expects or anticipates will or may occur in the future, and are based on currently available information. Although Coeur believes that its expectations are based on reasonable assumptions, it can give no assurance that these expectations will prove correct. -

Mining Method Evaluation and Dilution Control in Kittilä Mine

Aalto University School of Engineering Degree Programme in Civil and Structural Engineering Eero Tommila Mining method evaluation and dilution control in Kittilä mine Master’s Thesis Espoo, May 5, 2014 Supervisor: Prof. Mikael Rinne Thesis advisor: M.Sc. André van Wageningen Aalto University, P.O. BOX 11000, 00076 AALTO www.aalto.fi Abstract of master's thesis Author Eero Tommila Title of thesis Mining method evaluation and dilution control in Kittilä mine Degree programme Structural and building technology Major/minor European mining course Code of professorship Rak-32 Thesis supervisor Prof. Mikael Rinne Thesis advisor M.Sc. André van Wageningen Date 05.05.2014 Number of pages 63 Language English Abstract Kittilä mine is a gold mine located in the Northern Finland. It began producing as an open pit mine but nowdays all the production comes from underground mine. The underground mining method was defined during the feasibility study with limited information. With the experience from the underground mining and more rock mechanical and geological data, this thesis was conducted to study if there could be more cost effective method for mining the ore and how to reduce the dilution. The study is divided into two parts: dilution control and mining method selection. Dilution control was done by identifying the reasons for dilution and examining their impact on Kittilä mine. After this, measures could be developed to decrease dilution and improve predictability. Mining method selection was performed by doing preliminary method selection with traditional mining method selection tools. This yielded several methods, which applicability for Kittilä mine was assessed by terms of safety, suitability, production, dilution & recovery and flexibility. -

Niosh Mining Program Review

NIOSH MINING PROGRAM REVIEW Table of Contents Panel Members/Affiliations .......................................................................................................................... 2 Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Background for the Review Process ............................................................................................................. 5 Scoring Model and Process ........................................................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................ 6 Panel Findings ............................................................................................................................................... 7 Disaster Prevention and Response ......................................................................................................... 7 Overview and Findings: ..................................................................................................................... 7 Panel responses to questions from NIOSH: ...................................................................................... 9 Ground Control ..................................................................................................................................... 10 Overview and Findings: .................................................................................................................. -

Bureau of Mines Publications and Articles, 1992-1993

Special Publication SP 13-94 BUREAU OF MINES PUBLICATIONS AND ARTICLES, 1992-1993 (with Subject and Author Index) u.s. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR The Library of Congress has catalogued this serial publication as follows: Z6736 .U759 U.S. Bureau of Mines List of Bureau of Mines publications and articles, with subject and author index. 1960- Washington, U.S. Govt. Print. Off. v.28cm. (Its Special publication) Supersedes the Bureau's List of publications, Bureau of Mines and List of journal articles by Bureau of Mines authors. 1. Mineral industries-Bibl. 2. U.S. Bureau of Mines-Bibl. (Series) Z6736.U759 61-64978 For sale by the U.S. Government Printing Office Superintendent of Documents, Mail Stop: SSOP, Washington, DC 20402-9328 ISBN 0-16-045065-9 ii CONTENTS Page Introduction ................................................................ 1 Sources for USBM publications . 2 Abandoned mine reports . 3 Bulletins . 3 Computer products. 3 Information circulars .......................................................... 4 Mineral commodity summaries ................................................... 15 Mineral industry surveys ....................................................... 16 Mineral institute reports ........................................................ 16 Mineral issues . .. 21 Mineral land assessment reports .................................................. 22 Mineral perspectives .......................................................... 24 Minerals yearbooks ........................................................... 25 Patents -

Mining Methods and Unit Operation

MINING METHODS AND UNIT OPERATION STUDY MATERIAL Mr. Rakesh Behera Assistant Professor Department of Mineral Engineering Government College Of Engineering Keonjhar, Odisha SYLLABUS Module I Surface Mining : Deposits amenable to surface mining ; Box Cut ; Objectives types parameters and methods, production benches- Objectives ,formation and benches parameters ,Unit Operation and associated equipments ,Classification of surface mining systems. Module II Underground Coal Mining: Deposits amenable to underground coal mining Classification of underground coal mining methods, Board and Pillar Methods –general description and applications and merits and demerits, selection of panel size operation involved and associated equipment. Module III Long Wall Methods –Type and their general description ,applicability ,merits and demerits ,Selection of face length and panel length ,operation involved and associated equipments, Methods for mining steeply inclined seam and thick seams hydraulic mining. Module IV Underground Metal Mining: Deposits amenable to underground metal mining shape, size &position of drifts and cross cut, Raises and Winzes, classification of underground metal mining methods. Module V Stoping Methods - General description, applicability, Oprations involved and associated equipments for room pillar mining, Stope and pillar mining, stope and piellar mining, shrinkage, stoping, sub level stoping ,cut and fill stoping, VCR methods, Sub level caving and caving . Surface Mining ▪ Surface mining is a form of mining in which the soil and the rock covering the mineral deposits are removed. It is the other way of underground mining, in which the overlying rock is left behind, and the required mineral deposits are removed through shafts or tunnels. ▪ The traditional cone-shaped excavation (although it can be any shape, depending on the size and shape of the ore body) that is used when the ore body is typically pipe-shaped, vein-type, steeply dipping stratified or irregular. -

Estimates of Electricity Requirements for the Recovery of Mineral Commodities, with Examples Applied to Sub-Saharan Africa

Estimates of Electricity Requirements for the Recovery of Mineral Commodities, with Examples Applied to Sub-Saharan Africa Open-File Report 2011–1253 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover. High voltage power lines over the San Andreas Fault at Cajon Pass, California. Photograph by Don Becker, U.S. Geological Survey. Estimates of Electricity Requirements for the Recovery of Mineral Commodities, with Examples Applied to Sub-Saharan Africa By Donald I. Bleiwas Open-File Report 2011–1253 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2011 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK– USGS For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Any use of trade, product, or names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Bleiwas, D.I., 2011, Estimates of electricity requirements for the recovery of mineral commodities, with examples applied to sub-Saharan Africa: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2011–1253, 100 p. ii Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Analytical Applications of Electricity Consumption Estimates ........................................................................................ 1 Limitations on Use of Estimates ................................................................................................................................... -

Coal Mining Methods

Coal Mining Methods Underground Mining In the extraction process, numerous pillars of coal are left untouched in certain parts of the Longwall & Room and Pillar Mining mine in order to support the overlying strata. The mined-out area is allowed to collapse, Longwall mining and room-and-pillar mining generally causing some surface subsidence. are the two basic methods of mining coal underground, with room-and-pillar being the traditional method in the United States. Both Extraction by longwall mining is an almost methods are well suited to extracting the continuous operation involving the use of self- relatively flat coalbeds (or coal seams) typical of advancing hydraulic roof supports, a the United States. Although widely used in sophisticated coal-shearing machine, and an other countries, longwall mining has only armored conveyor paralleling the coal face. recently become important in the United States, Working under the movable roof supports, the its share of total underground coal production shearing machine rides on the conveyor as it having grown from less than 5 percent before cuts and spills coal onto the conveyor for 1980 to about half in 2007. More than 85 transport out of the mine. When the shearer has longwalls operate in the United States, most of traversed the full length of the coal face, it them in the Appalachian region. reverses direction and travels back along the face taking the next cut. As the shearer passes In principle, longwall mining is quite simple each roof support, the support is moved closer to (Fig. 1). A coalbed is blocked out into a panel the newly cut face. -

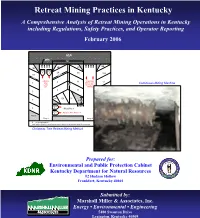

Retreat Mining Practices in Kentucky

Retreat Mining Practices in Kentucky A Comprehensive Analysis of Retreat Mining Operations in Kentucky including Regulations, Safety Practices, and Operator Reporting February 2006 GOB Posts 50' 9B 10B 1B 2B MRS MRS 1 2 2A 9A 0' 10A 1A '-4 20 25 '-5 0' Advance 4 11 Reposition 12 3 After MRS 1 and 2 Continuous Mining Machine Each 65' After Entry 1 Lift Mining 6 13 14 5 15B 15A 16 23B 23A 7 8' Min. MRS 8' Min. 8 3 Block No.1 Block No.2 MRS Advance After Each Lift 4 Barrier Entry 1 Entry 2 8 Lift mining sequence Install additional double rows of breaker posts in entries before and after certain lifts as required. Christmas Tree Retreat Mining Method Prepared for: Environmental and Public Protection Cabinet Kentucky Department for Natural Resources #2 Hudson Hollow Frankfort, Kentucky 40601 Submitted by: Marshall Miller & Associates, Inc. Energy • Environmental • Engineering 5480 Swanton Drive Lexington, Kentucky 40509 Retreat Mining Practices in Kentucky A Comprehensive Analysis of Retreat Mining Operations in Kentucky including Regulations, Safety Practices, and Operator Reporting February 2006 Prepared by: MMMAAARRRSSSHHHAAALLLLLL MMMIIILLLLLLEEERRR &&& AAASSSSSSOOOCCCIIIAAATTTEEESSS,,, IIINNNCCC... Energy • Environmental • Engineering 5480 Swanton Drive Lexington, Kentucky 40509 (859) 263-2855 • FAX (859) 263-2839 Bluefield, VA / Lexington, KY / Ashland, VA / Raleigh, NC / Camp Hill, PA / Kingsport, TN / Charleston, WV Copyright Notice The Contents of this document are protected by Copyright © to Marshall Miller & Associates, Inc. (MM&A). This report was prepared for the use of Kentucky Department for Natural Resources (KYDNR). KYDNR may freely distribute this publication to the regulated community and to the general public by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise. -

4Es L3Q3 'It Is Questionable If All the Mechanical Inventions Yet Made Have Lightened the Day's Toil of Any Human Being'

University of Newcastle upon Tyne TECHNICAL CHANGE AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF WORK: THE CASE OF THE BRITISH COAL INDUSTRY John Tomaney Submitted In fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Urban and Regional Development Studies Department of Geography University of Newcastle upon Tyne Newcastle upon Tyne 1991 1.j\l •t. 1 I........ iF I:; t :?j. :L•Ii X 4es L3Q3 'It is questionable if all the mechanical inventions yet made have lightened the day's toil of any human being' - John Stuart Mill, Principles of Political Economy, 1888. 'What', asked the French lecturer on the Science of Metals and Mining, 'is the most important thing to come out of a coal-mine?' 'Coal', replied the students. 'No', said the lecturer, Frederic Le Play, 'the most important thing is the coal-miner'. - F.D. Gould 'Le Play', Sociological Review, (1927) 1 ABSTRACT This thesis examines the suggestion that dramatic changes are occurring in the organisation of work and production, and that these amount to the emergence of a new 'post-Fordist' industrial paradigm. In particular, the claim that introduction of new forms of microelectronic-based technologies is leading to the emergence of new forms of skilled work, and that, as a result, old forms of industrial conflict are ameliorated, is analysed. The value of this conceptualisation of contemporary workplace change is questioned. A critique of the 'post-Fordist' argument is offered. This stresses: that new tendencies in the organisation of work can be discerned but that generally these are occurring alongside enduring forms of hierarchy and control; that the new forms of work and production represent a reformulation of traditional capitalist concerns of efficiency and control through the extension of 'flow principles'; and that the pattern of change in reality is highly uneven and spatially differentiated. -

Mechanized Longwall Mining, a Review Emphasizing Foreign Technology / by James J

re 874° Bureau of Mines Information Circular/1977 4 -SEP2 1 COPY .1 19/7 Mechanized Longwall Mining A Review Emphasizing Foreign Technology UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Information Circular, 8740 Mechanized Longwall Mining A Review Emphasizing Foreign Technology By James J. Olson and Sathit Tandanand UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Cecil D. Andrus, Secretary BUREAU OF MINES , As the Nation's principal conservation agency, the Department of the Interior has responsibility for most of our nationally owned public lands and natural resources. This includes fostering the wisest use of our land and water re- sources, protecting our fish and wildlife, preserving the environmental and cultural values of our national parks and historical places, and providing for the enjoyment of life through outdoor recreation. The Department assesses our energy and mineral resources and works to assure that their development is in the best interests of all our people. The Department also has a major re- sponsibility for American Indian reservation communities and for people who live in Island Territories under U.S. administration. This publication has been cataloged as follows: Olson, James J Mechanized longwall mining, a review emphasizing foreign technology / by James J. Olson and Sathit Tandanand. [Wash- ington] : Bureau of Mines, 1977. 201 p. : ill. ; 26 cm. (Information circular - Bureau of Mines ; 8740) Bibliography: p. 73*198. 1. Mining engineering. 2. Coal mining machinery. 3- Mining engi- neering - Bibliography. I. Tandanand, Sathit, joint author. II United States. Bureau of Mines. III. Title. IV. Title: Longwall mining. V. Series: United States. Bureau of Mines. Information circular - Bureau of Mines ; 8740.