Stark Widths of Ar II Spectral Lines in the Atmospheres of Subdwarf B Stars

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Search for Radio Pulsations from Neutron Star Companions of Four

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. 16098˙arxiv c ESO 2018 November 15, 2018 A search for radio pulsations from neutron star companions of four subdwarf B stars Thijs Coenen1, Joeri van Leeuwen2,1, and Ingrid H. Stairs3 1 Astronomical Institute ”Anton Pannekoek,” University of Amsterdam, P.O. Box 94249, 1090 GE, Amsterdam, The Netherlands 2 Stichting ASTRON, PO Box 2, 7990 AA Dwingeloo, The Netherlands 3 Dept. of Physics and Astronomy, University of British Columbia, 6224 Agricultural Road, Vancouver, B.C., V6T 1Z1 Canada ABSTRACT We searched for radio pulsations from the potential neutron star binary companions to subdwarf B stars HE 0532-4503, HE 0929- 0424, TON S 183 and PG 1232-136. Optical spectroscopy of these subdwarfs has indicated they orbit a companion in the neutron star mass range. These companions are thought to play an important role in the poorly understood formation of subdwarf B stars. Using the Green Bank Telescope we searched down to mean flux densities as low as 0.2 mJy, but no pulsed emission was found. We discuss the implications for each system. 1. Introduction Several such binary formation channels have been hypoth- esized. For an sdB to form, a light star must lose most of its The study of millisecond pulsars (MSPs) enables several types hydrogen envelope and ignite helium in its core. In these binary of research in astrophysics, ranging from binary evolution (e.g. systems, sdB stars can be formed through phases of Common Edwards & Bailes, 2001), to the potential detection of back- Envelope evolution where the envelope is ejected, or through ground gravitational radiation using a large set of pulsars with stable Roche Lobe overflow stripping the donor star of its hydro- stable timing properties (Jaffe & Backer, 2003). -

A Stripped Helium Star in the Potential Black Hole Binary LB-1 A

A&A 633, L5 (2020) Astronomy https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201937343 & c ESO 2020 Astrophysics LETTER TO THE EDITOR A stripped helium star in the potential black hole binary LB-1 A. Irrgang1, S. Geier2, S. Kreuzer1, I. Pelisoli2, and U. Heber1 1 Dr. Karl Remeis-Observatory & ECAP, Astronomical Institute, Friedrich-Alexander University Erlangen-Nuremberg (FAU), Sternwartstr. 7, 96049 Bamberg, Germany e-mail: [email protected] 2 Institut für Physik und Astronomie, Universität Potsdam, Karl-Liebknecht-Str. 24/25, 14476 Potsdam, Germany Received 18 December 2019 / Accepted 1 January 2020 ABSTRACT +11 Context. The recently claimed discovery of a massive (MBH = 68−13 M ) black hole in the Galactic solar neighborhood has led to controversial discussions because it severely challenges our current view of stellar evolution. Aims. A crucial aspect for the determination of the mass of the unseen black hole is the precise nature of its visible companion, the B-type star LS V+22 25. Because stars of different mass can exhibit B-type spectra during the course of their evolution, it is essential to obtain a comprehensive picture of the star to unravel its nature and, thus, its mass. Methods. To this end, we study the spectral energy distribution of LS V+22 25 and perform a quantitative spectroscopic analysis that includes the determination of chemical abundances for He, C, N, O, Ne, Mg, Al, Si, S, Ar, and Fe. Results. Our analysis clearly shows that LS V+22 25 is not an ordinary main sequence B-type star. The derived abundance pattern exhibits heavy imprints of the CNO bi-cycle of hydrogen burning, that is, He and N are strongly enriched at the expense of C and O. -

Evolution of Helium Star Plus Carbon-Oxygen White Dwarf Binary Systems and Implications for Diverse Stellar Transients and Hypervelocity Stars

A&A 627, A14 (2019) https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201935322 Astronomy c ESO 2019 & Astrophysics Evolution of helium star plus carbon-oxygen white dwarf binary systems and implications for diverse stellar transients and hypervelocity stars P. Neunteufel1, S.-C. Yoon2, and N. Langer1 1 Argelander Institut für Astronomy (AIfA), University of Bonn, Auf dem Hügel 71, 53121 Bonn, Germany e-mail: [email protected] 2 Department of Physics and Astronomy, Seoul National University, 599 Gwanak-ro, Gwanak-gu, Seoul 151-742, Korea Received 20 February 2019 / Accepted 28 April 2019 ABSTRACT Context. Helium accretion induced explosions in CO white dwarfs (WDs) are considered promising candidates for a number of observed types of stellar transients, including supernovae (SNe) of Type Ia and Type Iax. However, a clear favorite outcome has not yet emerged. Aims. We explore the conditions of helium ignition in the WD and the final fates of helium star-WD binaries as functions of their initial orbital periods and component masses. Methods. We computed 274 model binary systems with the Binary Evolution Code, in which both components are fully resolved. Both stellar and orbital evolution were computed including mass and angular momentum transfer, tides, gravitational wave emission, differential rotation, and internal hydrodynamic and magnetic angular momentum transport. We worked out the parts of the parameter space leading to detonations of the accreted helium layer on the WD, likely resulting in the complete disruption of the WD to deflagrations, where the CO core of the WD may remain intact and where helium ignition in the WD is avoided. -

White Dwarf and Hot Subdwarf Binaries As Possible Progenitors of Type I A

White dwarf and hot sub dwarf binaries as p ossible progenitors of type I a Sup ernovae Christian Karl July White dwarf and hot sub dwarf binaries as p ossible progenitors of type I a Sup ernovae Den Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultaten der FriedrichAlexanderUniversitatErlangenN urnberg zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades vorgelegt von Christian Karl aus Bamberg Als Dissertation genehmigt von den Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultaten der UniversitatErlangenN urnberg Tag der m undlichen Pr ufung Aug Vositzender der Promotionskommission Prof Dr L Dahlenburg Erstb erichterstatter Prof Dr U Heb er Zweitberichterstatter Prof Dr K Werner Contents The SPY pro ject Selection of DB white dwarfs Color criteria Absorption line criteria Summary of the DB selection The UV Visual Echelle Sp ectrograph Instrumental setup UVES data reduction ESO pip elin e vs semiautomated pip eline Derivation of system parameters Denition of samples Radial velocity curves Followup observations Radial velocity measurements Power sp ectra and RV curves Gravitational redshift Quantitative sp ectroscopic analysis Stellar parameters of singleline d systems -

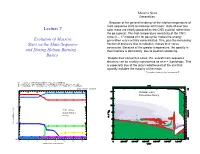

Lecture 7 Evolution of Massive Stars on the Main Sequence and During

Massive Stars Generalities: Because of the general tendency of the interior temperature of main sequence stars to increase with mass*, stars of over two Lecture 7 solar mass are chiefly powered by the CNO cycle(s) rather than the pp cycle(s). The high temperature sensitivity of the CNO cycle (n = 17 instead of 4 for pp-cycle) makes the energy Evolution of Massive generation very centrally concentrated. This, plus the increasing Stars on the Main Sequence fraction of pressure due to radiation, makes their cores convective. Because of the greater temperature, the opacity in and During Helium Burning - their interiors is dominantly due to electron scattering. Basics Despite their convective cores, the overall main sequence structure can be crudely represented as an n = 3 polytrope. This is especially true of the outer radiative part of the star that typically includes the majority of the mass. * To provide a luminosity that increases as M3 s15 3233 2.19951015502790E+14 c12( 1)= 7.5000E+10 R = 4.3561E+11 Teff = 2.9729E+04 L = 1.0560E+38 Iter = 37 Zb = 61 inv = 66 Dc = 5.9847E+00 Tc = 3.5466E+07 Ln = 6.9735E+36 Jm = 1048 Etot = -9.741E+49 B star 10,000 – 30,000 K 1 HHHHH 15 Solar mass He He HeH Convective history HH He He He He He .1 15 M half way ⊙ through hydrogen burning Elemental Mass Fraction .01 N N N O OOOO N C C N C Fe Fe Fe Fe Fe Fe Fe Fe IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIINeIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII NeIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII!,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,, Ne,,I,,,,,,,,,,Ii,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,I,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,, Ne,,,,,,,,,,,,........................................................................................................... -

EC 10246-2707: a New Eclipsing Sdb+ M Dwarf Binary

Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 000, 000–000 (0000) Printed 10 September 2018 (MN LATEX style file v2.2) EC 10246-2707: a new eclipsing sdB + M dwarf binary⋆ B.N. Barlow1,2†, D. Kilkenny3, H. Drechsel4, B.H. Dunlap2, D. O’Donoghue5,6, S. Geier4, R.G. O’Steen2, J.C. Clemens2, A.P. LaCluyze7, D.E. Reichart2,7, J.B. Haislip7, M.C. Nysewander7, K.M. Ivarsen7 1Department of Astronomy & Astrophysics, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16801, USA 2Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3255, USA 3Department of Physics, University of the Western Cape, Private Bag X17, Bellville 7535, South Africa 4Dr. Karl Remeis-Observatory & ECAP, Astronomical Institute, Friedrich-Alexander University Erlangen-Nuremberg, Sternwartstr. 7, D 96049 Bamberg, Germany 5South African Astronomical Observatory, PO Box 9, 7935 Observatory, Cape Town, South Africa 6Southern African Large Telescope Foundation, PO Box 9, 7935 Observatory, Cape Town, South Africa 7Skynet Robotic Telescope Network, Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3255, USA 10 September 2018 ABSTRACT We announce the discovery of a new eclipsing hot subdwarf B + M dwarf binary, EC 10246-2707, and present multi-colour photometric and spectroscopic observations of this system. Similar to other HW Vir-type binaries, the light curve shows both primary and secondary eclipses, along with a strong reflection effect from the M dwarf; no intrinsic light contribution is detected from the cool companion. The orbital period is 0.118 507 993 6 ± 0.0000000009 days, or about three hours. -

A Search for Radio Pulsations from Neutron Star Companions of Four Subdwarf B Stars

A&A 531, A125 (2011) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201016098 & c ESO 2011 Astrophysics A search for radio pulsations from neutron star companions of four subdwarf B stars T. Coenen1, J. van Leeuwen2,1, and I. H. Stairs3 1 Astronomical Institute “Anton Pannekoek”, University of Amsterdam, PO Box 94249, 1090 GE Amsterdam, The Netherlands e-mail: [email protected] 2 Stichting ASTRON, PO Box 2, 7990 AA Dwingeloo, The Netherlands 3 Dept. of Physics and Astronomy, University of British Columbia, 6224 Agricultural Road, Vancouver, B.C., V6T 1Z1, Canada Received 8 November 2010 / Accepted 29 May 2011 ABSTRACT We searched for radio pulsations from the potential neutron star binary companions to subdwarf B stars HE 0532-4503, HE 0929- 0424, TON S 183 and PG 1232-136. Optical spectroscopy of these subdwarfs has indicated they orbit a companion in the neutron star mass range. These companions are thought to play an important role in the poorly understood formation of subdwarf B stars. Using the Green Bank Telescope we searched down to mean flux densities as low as 0.2 mJy, but no pulsed emission was found. We discuss the implications for each system. Key words. stars: neutron – pulsars: general – subdwarfs 1. Introduction insensitivity of their survey to longer-period binaries, Maxted et al. (2001) conclude that binary star evolution is fundamental The study of millisecond pulsars (MSPs) enables several types to the formation of sdB stars. of research in astrophysics, ranging from binary evolution (e.g. Several such binary formation channels have been hypoth- Edwards & Bailes 2001), to the potential detection of back- esized. -

Variable Star

Variable star A variable star is a star whose brightness as seen from Earth (its apparent magnitude) fluctuates. This variation may be caused by a change in emitted light or by something partly blocking the light, so variable stars are classified as either: Intrinsic variables, whose luminosity actually changes; for example, because the star periodically swells and shrinks. Extrinsic variables, whose apparent changes in brightness are due to changes in the amount of their light that can reach Earth; for example, because the star has an orbiting companion that sometimes Trifid Nebula contains Cepheid variable stars eclipses it. Many, possibly most, stars have at least some variation in luminosity: the energy output of our Sun, for example, varies by about 0.1% over an 11-year solar cycle.[1] Contents Discovery Detecting variability Variable star observations Interpretation of observations Nomenclature Classification Intrinsic variable stars Pulsating variable stars Eruptive variable stars Cataclysmic or explosive variable stars Extrinsic variable stars Rotating variable stars Eclipsing binaries Planetary transits See also References External links Discovery An ancient Egyptian calendar of lucky and unlucky days composed some 3,200 years ago may be the oldest preserved historical document of the discovery of a variable star, the eclipsing binary Algol.[2][3][4] Of the modern astronomers, the first variable star was identified in 1638 when Johannes Holwarda noticed that Omicron Ceti (later named Mira) pulsated in a cycle taking 11 months; the star had previously been described as a nova by David Fabricius in 1596. This discovery, combined with supernovae observed in 1572 and 1604, proved that the starry sky was not eternally invariable as Aristotle and other ancient philosophers had taught. -

Gamma-Ray Burst Progenitors

Space Sci Rev (2016) 202:33–78 DOI 10.1007/s11214-016-0312-x Gamma-Ray Burst Progenitors Andrew Levan1 · Paul Crowther2 · Richard de Grijs3,4 · Norbert Langer5 · Dong Xu6,7,8 · Sung-Chul Yoon9 Received: 26 August 2016 / Accepted: 8 November 2016 / Published online: 21 November 2016 © The Author(s) 2016. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract We review our current understanding of the progenitors of both long and short duration gamma-ray bursts (GRBs). Constraints can be derived from multiple directions, and we use three distinct strands; (i) direct observations of GRBs and their host galaxies, (ii) parameters derived from modelling, both via population synthesis and direct numerical simulation and (iii) our understanding of plausible analog progenitor systems observed in the local Universe. From these joint constraints, we describe the likely routes that can drive B A. Levan [email protected] P. Crowther Paul.crowther@sheffield.ac.uk R. de Grijs [email protected] N. Langer [email protected] D. Xu [email protected] S.-C. Yoon [email protected] 1 Department of Physics, University of Warwick, Coventry, CV4 7AL, UK 2 Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Sheffield, Sheffield S3 7RH, UK 3 Kavli Institute for Astronomy & Astrophysics and Department of Astronomy, Peking University, Yi He Yuan Lu 5, Hai Dian District, Beijing 100871, China 4 International Space Science Institute–Beijing, 1 Nanertiao, Zhongguancun, Hai Dian District, Beijing 100190, China 5 Argelander-Institut für Astronomie der Universität Bonn, Auf dem Hügel 71, 53121, Bonn, Germany 6 Dark Cosmology Centre, Niels-Bohr-Institute, University of Copenhagen, Juliane Maries Vej 30, 2100 Copenhagen, Denmark 7 National Astronomical Observatories, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100012, China 34 A. -

Super-AGB Stars and Their Role As Electron Capture Supernova

Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia (PASA) c Astronomical Society of Australia 2017; published by Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/pas.2017.xxx. Super-AGB Stars and their role as Electron Capture Supernova progenitors Carolyn L. Doherty1,2, Pilar Gil-Pons3,4 Lionel Siess5, and John C. Lattanzio2 1Konkoly Observatory, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, 1121 Budapest 2Monash Centre for Astrophysics, School of Physics and Astronomy, Monash University, Australia 3Polytechnical University of Catalonia, Barcelona, Spain 4Institut d’Estudis Espacials de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain 5Institut d’Astronomie et d’Astrophysique, Universit´eLibre de Bruxelles, ULB, Belgium Abstract We review the lives, deaths and nucleosynthetic signatures of intermediate mass stars in the range ≈ 6.5–12 M⊙, which form super-AGB stars near the end of their lives. We examine the critical mass boundaries both between different types of massive white dwarfs (CO, CO-Ne, ONe) and between white dwarfs and supernovae and discuss the relative fraction of super-AGB stars that end life as either an ONe white dwarf or as a neutron star (or an ONeFe white dwarf), af- ter undergoing an electron capture supernova. We also discuss the contribution of the other potential single-star channels to electron-capture supernovae, that of the failed massive stars. We describe the factors that influence these different final fates and mass limits, such as composition, the efficiency of convection, rotation, nuclear reaction rates, mass loss rates, and third dredge-up efficiency. We stress the importance of the binary evolution channels for producing electron-capture supernovae. We discuss recent nucleosynthesis calculations and elemental yield results and present a new set of s-process heavy element yield predictions. -

Pre-Supernova Evolution of Massive Stars

Chapter 12 Pre-supernova evolution of massive stars We have seen that low- and intermediate-mass stars (with masses up to ≈ 8 M⊙) develop carbon- oxygen cores that become degenerate after central He burning. As a consequence the maximum core temperature reached in these stars is smaller than the temperature required for carbon fusion. During the latest stages of evolution on the AGB these stars undergo strong mass loss which removes the remaining envelope, so that their final remnants are C-O white dwarfs. The evolution of massive stars is different in two important ways: • They reach a sufficiently high temperature in their cores (> 5×108 K) to undergo non-degenerate carbon ignition (see Fig. 12.1). This requires a certain minimum mass for the CO core after central He burning, which detailed evolution models put at MCO−core > 1.06 M⊙. Only stars with initial masses above a certain limit, often denoted as Mup in the literature, reach this criti- cal core mass. The value of Mup is somewhat uncertain, mainly due to uncertainties related to mixing (e.g. convective overshooting), but is approximately 8 M⊙. Stars with masses above the limit Mec ≈ 11 M⊙ also ignite and burn fuels heavier than carbon until an Fe core is formed which collapses and causes a supernova explosion. We will explore the evolution of the cores of massive stars through carbon burning, up to the formation of an iron core, in the second part of this chapter. • For masses M >∼ 15 M⊙, mass loss by stellar winds becomes important during all evolution phases, including the main sequence. -

Variability of Hot Subdwarf Stars from the Palomar-Green Catalog of Ultraviolet Excess Stellar Objects

ABSTRACT VARIABILITY OF HOT SUBDWARF STARS FROM THE PALOMAR-GREEN CATALOG OF ULTRAVIOLET EXCESS STELLAR OBJECTS This thesis presents a survey for variability in 985 objects identified as hot subdwarf stars by the Palomar-Green Catalog of Ultraviolet Excess Stellar Objects. Catalina Real-Time Transient Survey (CRTS) light curves are used to find the variability. Landolt standard stars that are also hot subdwarf stars in the Palomar-Green Catalog are used to calibrate CRTS photometry in the visual (V) band, and show it is accurate to within ΔV = 0.1 magnitudes between V = 12.0 and V = 16.0. Eleven objects are found to have variability that exceeds four standard deviations above the means of their CRTS light curves. Two are objects already known to be variable. They are PG 1101+385 (Mrk 421), a BL Lac object, and PG 1419+081, a short-period, pulsating sdB star. The other nine are new discoveries of variability: PG 0901+309, PG 0923+329, PG 0934+554, PG 1201+258, PG 1025+244, PG 1411+219, PG 1640+645, PG 1700+315, and PG 2217+059. PG 0934+554 is a spectrophotometric standard of Massey et al. (1988): this discovery of its variability shows that it should not be used as a standard. PG 0934+554 is identified as a BL Lac object. More tentative identifications include PG 1411+219 as an AM CVn star, PG 1640+645 and PG 2217+059 as dwarf novae, and PG 1700+315 as an eclipsing binary star system. Detailed follow-up observations are needed for the other variables, although they may be pulsating hot subdwarf stars.