The Ethos of Slam Poetry James W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Tuscan Child

PRAISE FOR RHYS BOWEN’S IN FARLEIGH FIELD “Well-crafted, thoroughly entertaining.” —Publishers Weekly “The skills Bowen brings . inform the plotting in this character-rich tale, which will be welcomed by her fans as well as by readers who enjoy fiction about the British home front.” —Booklist “In what could easily become a PBS show of its own, Bowen’s novel winningly details a World War II spy game.” —Library Journal “This novel will keep readers deeply involved until the end.” —Portland Book Review “In Farleigh Field delivers the same entertainment mixed with intellectual intrigue and realistic setting for which Bowen has earned awards and loyal fans.” —New York Journal of Books “Well-plotted and thoroughly entertaining . With characters who are so fully fleshed out, you can imagine meeting them on the street.” —Historical Novel Society “Through the character’s eyes, readers will be drawn into the era and begin to understand the sacrifices and hardships placed on English society.” —Crimespree Magazine “A thrill a minute . highly recommend.” —Night Owl Reviews, Top Pick “Riveting.” —Military Press “Instantly absorbing, suspenseful, romantic and stylish—like binge- watching a great British drama on Masterpiece Theatre.” —Lee Child, New York Times bestselling author “In Farleigh Field is brilliant. The plotting is razor sharp and ingenious, the setting in World War Two Britain is so tangible it’s eerie. The depth and breadth of character is astonishing. They’re likeable and repulsive and warm and stand-offish. And oh, so human. And so relatable. This is magnificently written and a must read.” —Louise Penny, New York Times bestselling author “Irresistible, charming and heartbreakingly authentic. -

SLAM AS METHODOLOGY: THEORY, PERFORMANCE, PRACTICE by Nishalini Michelle Patmanathan a Thesis Submitted in Conformity with the R

SLAM AS METHODOLOGY: THEORY, PERFORMANCE, PRACTICE by Nishalini Michelle Patmanathan A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Department of Curriculum, Teaching and Learning Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto © Copyright by Nishalini Michelle Patmanathan (2014) SLAM AS METHODOLOGY: THEORY, PERFORMANCE, PRACTICE Nishalini Michelle Patmanathan Master of Arts Department of Curriculum, Teaching and Learning Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto 2014 ABSTRACT This thesis study theorizes slam as a research methodology in order to examine issues of access and representation in arts-based educational research (ABER). I explain how I understand and materialize slam as a research methodology that borrows concepts and frameworks from other methodologies such as, ABER, participatory action research (PAR) and theoretical underpinnings of indigenous theory, feminist theory and anti- oppressive research. I argue that ABER and slam, as a particular form of ABER, needs to ‘unart’ each other to avoid trying to situate slam within the Western canon of ‘high arts’. I apply PAR methodology to discuss participant involvement in the research process and use anti-oppressive research to speak about power and race in slam. Finally, I argue that a slam research methodology has the ability to enable critically conscious communities. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am overflowing with gratitude. A great deal of this is due to the loving, inspiring and wise community of family, friends, and professors, with whom I have been blessed with. Most importantly, I would like to thank my parents, whose passion for learning and pursuit of university education despite impossibly difficult conditions were sources of inspiration and strength throughout my studies. -

Performance Poetry New Languages and New Literary Circuits?

Performance Poetry New Languages and New Literary Circuits? Cornelia Gräbner erformance poetry in the Western world festival hall. A poem will be performed differently is a complex field—a diverse art form that if, for example, the poet knows the audience or has developed out of many different tradi- is familiar with their context. Finally, the use of Ptions. Even the term performance poetry can easily public spaces for the poetry performance makes a become misleading and, to some extent, creates strong case for poetry being a public affair. confusion. Anther term that is often applied to A third characteristic is the use of vernacu- such poetic practices is spoken-word poetry. At lars, dialects, and accents. Usually speech that is times, they are included in categories that have marked by any of the three situates the poet within a much wider scope: oral poetry, for example, or, a particular community. Oftentimes, these are in the Spanish-speaking world, polipoesía. In the marginalized communities. By using the accent in following pages, I shall stick with the term perfor- the performance, the poet reaffirms and encour- mance poetry and briefly outline some of its major ages the use of this accent and therefore, of the characteristics. group that uses it. One of the most obvious features of perfor- Finally, performance poems use elements that mance poetry is the poet’s presence on the site of appeal to the oral and the aural, and not exclu- the performance. It is controversial because the sively to the visual. This includes music, rhythm, poet, by enunciating his poem before the very recordings or imitations of nonverbal sounds, eyes of his audience, claims authorship and takes smells, and other perceptions of the senses, often- responsibility for it. -

Hip Hop, Memes, and the Internet

BY ALL MEMES NECESSARY: HIP HOP, MEMES, AND THE INTERNET MAX TRETTER FRIEDRICH-ALEXANDER-UNIVERSITY ERLANGEN-NUREMBERG INTRODUCTION: HIP HOP ON THE INTERNET The internet influences hip hop in various ways. First and foremost, the internet is a medium that opens up a new space and stage in which hip hop can be performed. This stage is no longer local, but global, which represents both opportunity and challenge. On the one hand, each hip hop artist must assert themselves against countless compet- itors from all over the world; on the other hand, their breakthrough online, if it suc- ceeds, can be monumental in comparison to an analog breakthrough, which is usually confined to a limited area. Therefore, for hip hop artists it is increasingly important to attract attention – as only those who get the attention succeed in this new medium (Prior 2018, Jenkins et al. 2013). The internet’s central influence on hip hop is the inten- sification of the battle for attention – which results in hip hop artists trying new ap- proaches and strategies to gain that attention. One of them is producing their content with an eye to making it as meme-able as possible and capitalizing on meme dynamics on the internet. In this study, I approach memes as a concept, following the definition of Dawkins (2006) who originally defined the concept of memes in his work The Selfish Gene. Memes are small units of information that are usually very simple and catchy (ges- tures, styles, melodies, or phrases). They are transmitted from person to person by imitation or adaption, replicate and spread very quickly, and contribute to the dissem- ination and formation of common behaviors and cultures (Dawkins 2006). -

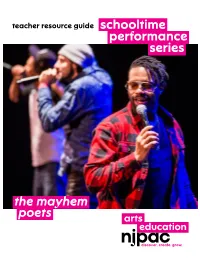

The Mayhem Poets Resource Guide

teacher resource guide schooltime performance series the mayhem poets about the who are in the performance the mayhem poets spotlight Poetry may seem like a rarefied art form to those who Scott Raven An Interview with Mayhem Poets How does your professional training and experience associate it with old books and long dead poets, but this is inform your performances? Raven is a poet, writer, performer, teacher and co-founder Tell us more about your company’s history. far from the truth. Today, there are many artists who are Experience has definitely been our most valuable training. of Mayhem Poets. He has a dual degree in acting and What prompted you to bring Mayhem Poets to the stage? creating poems that are propulsive, energetic, and reflective Having toured and performed as The Mayhem Poets since journalism from Rutgers University and is a member of the Mayhem Poets the touring group spun out of a poetry of current events and issues that are driving discourse. The Screen Actors Guild. He has acted in commercials, plays 2004, we’ve pretty much seen it all at this point. Just as with open mic at Rutgers University in the early-2000s called Mayhem Poets are injecting juice, vibe and jaw-dropping and films, and performed for Fiat, Purina, CNN and anything, with experience and success comes confidence, Verbal Mayhem, started by Scott Raven and Kyle Rapps. rhymes into poetry through their creatively staged The Today Show. He has been published in The New York and with confidence comes comfort and the ability to be They teamed up with two other Verbal Mayhem regulars performances. -

A Teacher's Resource Guide for the Mayhem Poets

A Teacher’s Resource Guide for The Mayhem Poets Slam in the Schools Thursday, January 28 10 a.m. Schwab Auditorium Presented by The Center for the Performing Arts at Penn State The school-time matinees are supported, in part, by McQuaide Blasko Busing Subsidy in part by the Honey & Bill Jaffe Endowment for Audience Development The Pennsylvania Council on the Arts provides season support 1 Table of Contents Welcome to the Center for the Performing Arts presentation of The Mayhem Poets ................................ 3 Pre-performance Activity: Role of the Audience .......................................................................................... 4 Best Practices for Audience Members ...................................................................................................... 4 About the Mayhem Poets ............................................................................................................................. 5 Slam poetry--the competitive art of performance poetry ............................................................................ 7 Slam Poetry--Frequently Asked Questions ............................................................................................... 8 Slam Poetry Philosophies ........................................................................................................................ 16 Taken from the website http://www.slampapi.com/new_site/background/philosophies.htm. .......... 16 Suggested Activity: Poetic Perspective ...................................................................................................... -

The Digital Deli Online - List of Known Available Shows As of 01-01-2003

The Digital Deli Online - List of Known Available Shows as of 01-01-2003 $64,000 Question, The 10-2-4 Ranch 10-2-4 Time 1340 Club 150th Anniversary Of The Inauguration Of George Washington, The 176 Keys, 20 Fingers 1812 Overture, The 1929 Wishing You A Merry Christmas 1933 Musical Revue 1936 In Review 1937 In Review 1937 Shakespeare Festival 1939 In Review 1940 In Review 1941 In Review 1942 In Revue 1943 In Review 1944 In Review 1944 March Of Dimes Campaign, The 1945 Christmas Seal Campaign 1945 In Review 1946 In Review 1946 March Of Dimes, The 1947 March Of Dimes Campaign 1947 March Of Dimes, The 1948 Christmas Seal Party 1948 March Of Dimes Show, The 1948 March Of Dimes, The 1949 March Of Dimes, The 1949 Savings Bond Show 1950 March Of Dimes 1950 March Of Dimes, The 1951 March Of Dimes 1951 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1951 March Of Dimes On The Air, The 1951 Packard Radio Spots 1952 Heart Fund, The 1953 Heart Fund, The 1953 March Of Dimes On The Air 1954 Heart Fund, The 1954 March Of Dimes 1954 March Of Dimes Is On The Air With The Fabulous Dorseys, The 1954 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1954 March Of Dimes On The Air 1955 March Of Dimes 1955 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1955 March Of Dimes, The 1955 Pennsylvania Cancer Crusade, The 1956 Easter Seal Parade Of Stars 1956 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1957 Heart Fund, The 1957 March Of Dimes Galaxy Of Stars, The 1957 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1957 March Of Dimes Presents The One and Only Judy, The 1958 March Of Dimes Carousel, The 1958 March Of Dimes Star Carousel, The 1959 Cancer Crusade Musical Interludes 1960 Cancer Crusade 1960: Jiminy Cricket! 1962 Cancer Crusade 1962: A TV Album 1963: A TV Album 1968: Up Against The Establishment 1969 Ford...It's The Going Thing 1969...A Record Of The Year 1973: A Television Album 1974: A Television Album 1975: The World Turned Upside Down 1976-1977. -

Introduction M Priorities

Mose_0771065043_xp_01_r1.qxd 9/25/06 3:40 PM Page 1 We Contain Multitudes: Our Many Roles, Many Selves introduction anager, professional, mentor, mother, wife, volunteer, artist, friend, athlete. Never before M have there been so many demands on women to excel in so many domains of life, so many opportuni- ties for self-expression and success, for disappointment and frustration. Our sense of self is nuanced, intricate, and rich. We derive our feelings of satisfaction from multi- ple roles. Freud famously said: “Love and work are the corner- stone of our humanness.” If we augment “love” to include our friends and our passions and “work” to include paid and unpaid activity, this is all that matters. These are the issues we are particularly likely to reflect on at midlife, a time of significant opportunities and chal- lenges when we take stock and ask, “What next?” and “How can I feel better about my life?” and reevaluate our priorities. 1 Mose_0771065043_xp_01_r1.qxd 9/25/06 3:40 PM Page 2 2 Women Confidential We have so many needs and desires. In my career/life-planning workshops with managers and professionals, I am always aware of the different ways in which men and women identify and rank their values. The most striking difference is not in the values themselves or how they are ranked, although there are differences, but in how the lists are completed. The men finish the exercise in a few minutes and move on to the next question. The women write the list. Then they erase it. Then they do it again. -

Calderon, Nicholas Interview 2 Calderon, Nicholas

Fordham University Masthead Logo DigitalResearch@Fordham Oral Histories Bronx African American History Project 5-27-2010 Calderon, Nicholas Interview 2 Calderon, Nicholas. Bronx African American History Project Fordham University Follow this and additional works at: https://fordham.bepress.com/baahp_oralhist Part of the African American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Calderon, Nicholas. May 27, 2010. Interview with the Bronx African American History Project. BAAHP Digital Archive at Fordham University. This Interview is brought to you for free and open access by the Bronx African American History Project at DigitalResearch@Fordham. It has been accepted for inclusion in Oral Histories by an authorized administrator of DigitalResearch@Fordham. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Interviewee: Nicholas Calderon Interviewer: Mark Naison Date: May 27, 2010 Mark Naison (MN): Hello. Today is Thursday May 27th, 2010. This is the Bronx African American History Project and we’re dealing with the second interview with Nicholas Calderon aka Young Buggs. Leader Interviewer is Noel Wolfe, assisting is Mark Naison and our videographer is Dawn Russell. So Noel, take it away. Noel Wolfe (NW): So we last left off when we were talking about how you were shifting into music in a way from drug dealing and I wanted to start there. What did music provide you at that stage? You were 17 years old? Nicholas Calderon (NC): Yes mam. Basically my comfort because it wasn’t my home, so music was a way out to get away from that temporarily though. MN: Now we’re talking about music, were you thinking about being a leader assist like writing rhymes and telling stories? NC: That’s what mainly it was about. -

High Fidelity

HIGH FIDELITY A MUSICAL COMEDY BY Amanda Green, Tom Kitt, and David Lindsay-Abaire BASED ON THE NOVEL BY NICK HORNBY AND THE TOUCHSTONE PICTURES FILM HIGH SCHOOL EDITION SHOW PERUSAL 11/07/19 High Fidelity - 1st ed. – 10.21.13 – highfidelity_conductor1cf Copyright © 2013 Amanda Green, Tom Kitt, and David Linsday Abaire ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Copyright Protection. This play (the “Play”) is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America and all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations, whether through bilateral or multilateral treaties or otherwise, and including, but not limited to, all countries covered by the Pan- American Copyright Convention, the Universal Copyright Convention, and the Berne Convention. Reservation of Rights. All rights to this Play are strictly reserved, including, without limitation, professional and amateur stage performance rights; motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video, and sound recording rights; rights to all other forms of mechanical or electronic reproduction now known or yet to be invented, such as CD-ROM, CD-I, DVD, photocopying, and information storage and retrieval systems; and the rights of translation into non-English languages. Performance Licensing and Royalty Payments. Amateur and stock performance rights to this Play are controlled exclusively by Broadway Licensing. No amateur or stock production groups or individuals may perform this Play without obtaining advance written permission from Broadway Licensing. Such royalty fees may be subject to change without notice. Although this book may have been obtained for a particular licensed performance, such performance rights, if any, are not transferable. -

Good Chemistry James J

Columbia College Fall 2012 TODAY Good Chemistry James J. Valentini Transitions from Longtime Professor to Dean of the College your Contents columbia connection. COVER STORY FEATURES The perfect midtown location: 40 The Home • Network with Columbia alumni Front • Attend exciting events and programs Ai-jen Poo ’96 gives domes- • Dine with a client tic workers a voice. • Conduct business meetings BY NATHALIE ALONSO ’08 • Take advantage of overnight rooms and so much more. 28 Stand and Deliver Joel Klein ’67’s extraordi- nary career as an attorney, educator and reformer. BY CHRIS BURRELL 18 Good Chemistry James J. Valentini transitions from longtime professor of chemistry to Dean of the College. Meet him in this Q&A with CCT Editor Alex Sachare ’71. 34 The Open Mind of Richard Heffner ’46 APPLY FOR The venerable PBS host MEMBERSHIP TODAY! provides a forum for guests 15 WEST 43 STREET to examine, question and NEW YORK, NY 10036 disagree. TEL: 212.719.0380 BY THOMAS VIncIGUERRA ’85, in residence at The Princeton Club ’86J, ’90 GSAS of New York www.columbiaclub.org COVER: LESLIE JEAN-BART ’76, ’77J; BACK COVER: COLIN SULLIVAN ’11 WITHIN THE FAMILY DEPARTMENTS ALUMNI NEWS Déjà Vu All Over Again or 49 Message from the CCAA President The Start of Something New? Kyra Tirana Barry ’87 on the successful inaugural summer of alumni- ete Mangurian is the 10th head football coach since there, the methods to achieve that goal. The goal will happen if sponsored internships. I came to Columbia as a freshman in 1967. (Yes, we you do the other things along the way.” were “freshmen” then, not “first-years,” and we even Still, there’s no substitute for the goal, what Mangurian calls 50 Bookshelf wore beanies during Orientation — but that’s a story the “W word.” for another time.) Since then, Columbia has compiled “The bottom line is winning,” he said. -

Silent Universe: Mission 256 1

SILENT UNIVERSE: MISSION 256 1. SILENT UNIVERSE Episode #1:“Mission 256” An original dramatic podcast by Julius Harper Edited by Kevin Rosenberg, Charity Tran, Jonathan Brent Bryce Chu, Will Anderegg, Kevin Lau PRODUCTION SCRIPT [DRAFT 7.0] StarKnight Productions & Planet Fandom www.planetfandom.com © 2005 Julius Harper [email protected] All Rights Reserved. StarKnight Productions. [email protected] SILENT UNIVERSE: MISSION 256 2. About the Silent Universe … The Silent Universe purposely breaks many of the molds of popular SciFi series, like Star Trek, turning the concept of a utopian future on it's ear. In the world of the Silent Universe , war and apathy have continued far into the future, leaving humanity shattered and still fighting against itself, even in space. In this dystopian vision, the modern specters of genocide, racism, xenophobia and chaos still exist. Amidst such a dim world, there are still heroes and people who believe that humanity can aspire to something better, but it is a bitter and difficult battle for those who fight for good ideals . StarKnight Productions. [email protected] SILENT UNIVERSE: MISSION 256 3. SILENT UNIVERSE Episode #1:“Mission 256” Prod. #6 CAST (in order of appearance. BolBoldddd denotes main cast) Announcer DB Cooper? Narrator Ross Douglas Female Voice Kelly West News Reporter Judith Knowles Emmeline Kaley Hilary Blair Jack Smyth Mark Oliver Seung Bogs ( J) Dait Abuchi Dave Carol Phillip Sacramento Army Officer 1 Stephen Murray Army NCOIC ( JA ) Takatsuna Mukai Call Girl 1 Melissa Hoffman Army Officer 2 Chris Dell Army Officer 3 Lance Allan Army Officer 5 Army Captain Evan Yeoman Isaac Walker James Higuchi Ritsu Kobayashi Debbie Munro Ben HernandHernandezezezez Esteban Silva May Kobayashi Kristi Stewart Garet Arrowny Phillip Sacramento Gordon Marcus George Washington III Gill Frye Nick DeLillo Computer Jodi Paige Radio Guy #1 Carl Magnuson Administrator DC Goode Japanese VA #1 Takatsuna Mukai StarKnight Productions.