What Notice Did

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monthly Review of the World Intellectual Property Organization

Published monthly Annual subscription : 145 Swiss francs Each monthly issue: 15 Swiss francs Copyright - ' year - No. 6 Monthly Review of the June 1988 World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) Contents NOTIFICATIONS CONCERNING TREATIES WIPO Convention. Accessions: Swaziland, Trinidad and Tobago 261 Madrid Convention. Accession: Peru 261 WIPO MEETINGS Photographic Works. Preparatory Document for and Report of the WIPO/Uncsco Committee of Governmental Experts ( Paris. April 18 to 22. 1988) 262 Third International Congress on the Protection of Intellectual Property (of Authors. Artists and Producers) (Lima. April 21 to 23. 1988) 282 STUDIES The Copyright Aspects of Parodies and Similar Works, by Andre Françon 283 CORRESPONDENCE Letter from Norway, by Fiirger Stuevold Lassen 288 ACTIVITIES OF OTHER ORGANIZATIONS International Copyright Society (INTERGU). Xlth Congress (Locamo. March 21 to 25. 1988) ' 300 BOOKS AND ARTICLES 301 CALENDAR OF MEETINGS 302 COPYRIGHT AND NEIGHBORING RIGHTS LAWS AND TREATIES (INSERT) Editor's Note SPAIN Law on Intellectual Property (No. 22. of November 11. 1987) {Articles 101 to 148 and Additional. Transitional and Repealed Provisions) Text 1-01 © WIPO 1988 Any reproduction of official notes or reports, articles and translations of laws or agreements, published ISSN 0010-8626 in this review, is authorized only with the prior consent of WIPO. NOTIFICATIONS CONCERNING TREATIES 261 Notifications Concerning Treaties WIPO Convention Accessions SWAZILAND The Government of Swaziland deposited, on of establishing its contribution towards the budget May 18, 1988, its instrument of accession to the of the WIPO Conference. Convention Establishing the World Intellectual The said Convention, as amended on October 2, Property Organization (WIPO), signed at Stock- 1979, will enter into force, with respect to Swazi- holm on July 14, 1967. -

The 2019 Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market: Some Progress, a Few Bad Choices, and an Overall Failed Ambition Séverine Dusollier

The 2019 Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market: Some progress, a few bad choices, and an overall failed ambition Séverine Dusollier To cite this version: Séverine Dusollier. The 2019 Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market: Some progress, a few bad choices, and an overall failed ambition. Common Market Law Review, Kluwer Law International, 2020, 57 (4), pp.979 - 1030. hal-03230170 HAL Id: hal-03230170 https://hal-sciencespo.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03230170 Submitted on 19 May 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. COMMON MARKET LAW REVIEW CONTENTS Vol. 57 No. 4 August 2020 Editorial comments: Not mastering the Treaties: The German Federal Constitutional Court’s PSPP judgment 965-978 Articles S. Dusollier, The 2019 Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market: Some progress, a few bad choices, and an overall failed ambition 979-1030 G. Marín Durán, Sustainable development chapters in EU free trade agreements: Emerging compliance issues 1031-1068 M. Penades Fons, The effectiveness of EU law and private arbitration 1069-1106 Case law A. Court of Justice EU judicial independence decentralized: A.K., M. -

Toward a Definition of Striking Similarity in Infringement Actions for Copyrighted Musical Works John R

Journal of Intellectual Property Law Volume 10 | Issue 1 Article 5 October 2002 Toward a Definition of Striking Similarity in Infringement Actions for Copyrighted Musical Works John R. Autry Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.uga.edu/jipl Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation John R. Autry, Toward a Definition of Striking Similarity in Infringement Actions for Copyrighted Musical Works, 10 J. Intell. Prop. L. 113 (2002). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.uga.edu/jipl/vol10/iss1/5 This Notes is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Georgia Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Intellectual Property Law by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Georgia Law. Please share how you have benefited from this access For more information, please contact [email protected]. Autry: Toward a Definition of Striking Similarity in Infringement Action NOTES TOWARD A DEFINITION OF STRIKING SIMILARITY IN INFRINGEMENT ACTIONS FOR COPYRIGHTED MUSICAL WORKS Federal jurists in the United States have had great difficulty formulating the appropriate standard by which to adjudicate an alleged infringement of a copyrighted musicalwork.' A plaintiff alleging copyright infringement must show ownership of a valid copyright and misappropriation of original elements of the at-issue work.' Proof of a valid copyright is easily met;3 however, establishing that a defendant copied the original elements of one's musical work can be onerous and time-consuming. Courts have searched (often, in vain) for a straightforward "test" that allows plaintiffs to introduce evidence appropriate to copyright causes of action but also acknowledges the unique nature of music among the subject matter covered by copyright law.5 Courts have defined two methods for proving substantive copying of an original work. -

Comparative Analysis of National Approaches on Voluntary Copyright Relinquishment

Comparative analysis of national approaches on voluntary copyright relinquishment Article (Published Version) Guadamuz, Andres (2014) Comparative analysis of national approaches on voluntary copyright relinquishment. Committee on Development and Intellectual Property (CDIP): Thirteenth Session. This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/49154/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk E CDIP/13/INF/10 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH DATE: APRIL 14, 2014 Committee on Development and Intellectual Property (CDIP) Thirteenth Session Geneva, May 19 to 23, 2014 COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF NATIONAL APPROACHES ON VOLUNTARY COPYRIGHT RELINQUISHMENT prepared by Dr. -

1076 (1909), Codified at 17 U.S.C

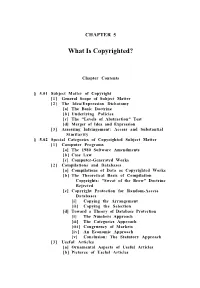

CHAPTER 5 What Is Copyrighted? Chapter Contents § 5.01 Subject Matter of Copyright [1] General Scope of Subject Matter [2] The Idea/Expression Dichotomy [a] The Basic Doctrine [b] Underlying Policies [c] The "Levels of Abstraction" Test [d] Merger of Idea and Expression [3] Assessing Infringement: Access and Substantial Similarity § 5.02 Special Categories of Copyrighted Subject Matter [1] Computer Programs [a] The 1980 Software Amendments [b] Case Law [c] Computer-Generated Works [2] Compilations and Databases [a] Compilations of Data as Copyrighted Works [b] The Theoretical Basis of Compilation Copyrights: "Sweat of the Brow" Doctrine Rejected [c] Copyright Protection for Random-Access Databases [i] Copying the Arrangement [ii] Copying the Selection [d] Toward a Theory of Database Protection [i] The Numbers Approach [ii] The Categories Approach [iii] Congruency of Markets [iv] An Economic Approach [v] Conclusion: The Statutory Approach [3] Useful Articles [a] Ornamental Aspects of Useful Articles [b] Pictures of Useful Articles [c] Plans, Drawings, and Models for Useful Articles [i] Eligibility of Plans, Drawings, and Models for Copyright Protection [ii] Limits on Protection [4] Architecture [a] The Separate Legal Regime for Building De- signs [b] Subject Matter Covered: Building Designs [c] Limitations on Copyright Protection for Building Designs [d] Prospectivity of Protection § 5.03 Prerequisites for Copyright Protection: Fixation, Originality, and Creativity [1] Fixation [a] New Technology [b] Communicative Function [c] What "Fixation" Means [i] Author's Authorization [ii] Tangible Medium and Permanence [d] Fixation and Interactive Systems [e] Fixation and Copyright Preemption [2] Originality [3] Creativity [4] What Copyright Does Not Require [a] The Difference Between Copyright and Patent Standards [b] Content and Copyright Protection § 5.01 Subject Matter of Copyright Patents and trade secrets may protect concepts in the broad sense. -

26Th Year - No

Copyright 26th year - No. 9 Monthly Review of the September 1990 World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) NOTIFICATIONS CONCERNING TREATIES Satellites Convention. Accession: Australia 239 Treaty on the International Registration of Audiovisual Works Ratifications: Austria. Burkina Faso 239 Approval: France 239 Treaty on Intellectual Property in Respect of Integrated Circuits. Ratification: Egypt .... 240 WIPO MEETINGS Committee of Experts on Model Provisions for Legislation in the Field of Copyright. Third Session (Geneva. July 2 to 13. 1990) 241 STUDIES Some Questions Underlying the Draft Model Provisions for Legislation in the Field of Copyright—A Pragmatic Approach, by Miguel Angel Emery1 302 CALENDAR OF MEETINGS 317 COPYRIGHT AND NEIGHBORING RIGHTS LAWS AND TREATIES (INSERT) Editor's Note GABON Law Instituting Protection for Copyright and Neighboring Rights (No. 1/87. of July 29. 1987) .' Text I —01 WIPO 1990 Any reproduction of official notes or reports, articles and translations of laws or agreements, published in this review, is authorized only with the prior consent of WIPO. NOTIFICATIONS CONCERNING TREATIES 239 Notifications Concerning Treaties Satellites Convention Accession AUSTRALIA The Secretary-General of the United Nations Transmitted by Satellite, adopted at Brussels on notified the Director General of the World Intellec- May 21. 1974. tual Property Organization that the Government of The said Convention will enter into force, for Australia deposited, on July 26, 1990, its instru- Australia, three months after the date of deposit of ment of accession to the Convention Relating to its instrument of accession, that is on October 26. the Distribution of Programme-Carrying Signals 1990. Treat}' on the International Registration of Audiovisual Works Ratifications AUSTRIA The Government of the Republic of Austria de- will be notified when the required number of ratifi- posited, on August 6, 1990. -

3. Interface Between Copyright and Human Rights

DELHI JOURNAL OF CONTEMPORARY LAW (VOL.I) INTERFACE BETWEEN COPYRIGHT AND HUMAN RIGHTS Archa Vashishtha* I. INTRODUCTION The hefty expansion of subject matters of IPRs led academicians likes James Boyle to define it as “second enclosure movement”. This time having subjects not lands but the result of the human intellect like copyright, patents etc. Different links have evolved over the time between various kinds of Intellectual Property and Human Rights. The roles of private property in human rights have always been controversial and this is so in the case of Intellectual property law and Human Rights interface as well. If we talk specifically about Copyright, copyright and Human Rights are two subjects that developed in absolute isolation of each other but from past few decades their intersections became common owing to development of various national and international instruments dealing with both human rights and copyright. The two are trying hard to reconcile and deal with the conflicting issues. As far as human rights are concerned every individual has his/her own conception of human rights. Simply put human rights are something that exists by virtue of humanity and nothing else. We don’t possess human rights because they are written somewhere but because they are the foundation of any independent society. Though, it is a different matter altogether that human rights have gained formal legal recognition and can be effectively enforced under various national and international instruments. Human rights approaches bring back values to the system. Human rights protect not only civil and political rights but also social, economic and cultural rights of the people. -

The Structure of Copyright Systems of France, Germany and Russia

ВЕСТНИК ПЕРМСКОГО УНИВЕРСИТЕТА. ЮРИДИЧЕСКИЕ НАУКИ 2016 PERM UNIVERSITY HERALD. JURIDICAL SCIENCES Выпуск 33 Information for citation: Matveev A. G. The Structure of Copyright Systems of France, Germany and Russia. Vestnik Permskogo univer- sita. Juridicheskie nauki – Perm University Herald. Juridical Sciences. 2016. Issue 33. Pp. 348–353. (In Eng.). DOI: 10.17072/1995-4190-2016-33-348-353. UDC 347.78 DOI: 10.17072/1995-4190-2016-33-348-353 THE STRUCTURE OF COPYRIGHT SYSTEMS OF FRANCE, GERMANY AND RUSSIA The author acknowledges the support of the Russian Foundation for Humanities (grant 15-03-00456) A. G. Matveev Perm State University 15, Bukireva st., Perm, 614990, Russia ORCID: 0000-0002-5808-939X ResearcherID: F-1946-2016 e-mail: [email protected] Introduction: as is known, there are two key copyright law traditions: Anglo-American and Romano-Germanic copyright laws. At the same time, copyright law of the main representatives of Romano-Germanic tradition is not homogeneous, as it may seem at first glance. French and German copyright law is in the vanguard of the continental copyright law, with the copyright law of Russia being among the others in this copyright law system. However, Russian copyright law has some specific characteristics. The purpose of the present article is to define the struc- ture of copyright systems of France, Germany and Russia. Methods: comparative legal, histor- ic, system structural and formal dogmatic methods are used in the analysis. Results: the article considers the influence of philosophical law theories on copyright systems in France, Germany and Russia. These systems are characterized in terms of correlation between the author’s eco- nomic and moral rights. -

Protecting Authors' Rights in a Digital Age

Maurer School of Law: Indiana University Digital Repository @ Maurer Law Articles by Maurer Faculty Faculty Scholarship 1995 Protecting Authors' Rights in a Digital Age Marshall A. Leaffer Indiana University Maurer School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/facpub Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Leaffer, Marshall A., "Protecting Authors' Rights in a Digital Age" (1995). Articles by Maurer Faculty. 611. https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/facpub/611 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by Maurer Faculty by an authorized administrator of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DOERMANN DISTINGUISHED LECTURER PROTECTING AUTHORS' RIGHTS IN A DIGITAL AGE Marshall Leaffer" Doermann DistinguishedLecturer" I FROM GUTENBERG TO ELECTRONIC NETWORKS The Background F OR the past twenty-five years I have been involved, in one way or another, in the Law of Copyright, and since 1978, I have taught a course on copyright law at the University of Toledo College of Law I am grateful to have this forum provided by the Doermann Distinguished Lecture Program, to talk about my subject with a group of people in and outside the legal profession In so doing, I do not plan to delve into the intricacies of copyright law, but to talk about the importance of this law that protects works -

Download This PDF File

ISSN 1712-8056[Print] Canadian Social Science ISSN 1923-6697[Online] Vol. 9, No. 1, 2013, pp. 1-8 www.cscanada.net DOI:10.3968/j.css.1923669720130901.1092 www.cscanada.org Terms of Use the Private Version of Protected Works Comparative Study Saleem Isaaf Alazab[a]; Ahmed Adnan Al-Nuemat[a],* [a] Assistant Professor of Law, AL-Balqa Applied University, Amman, the use if it is not targeted for purposes like commercial 11821 Jordan. purposes, making profit from it and to compete for * Corresponding author. economic purposes. Received 7 December 2012; accepted 29 January 2013 Key words: Copyright; Private version; Protected works; Copyright law of Egypt; Copyright law of France Abstract The authorities deem that for the author to make his/ Saleem Isaaf Alazab, Ahmed Adnan Al-Nuemat (2013). Terms of Use the Private Version of Protected Works Comparative Study. her work exclusive and yield full benefit from it the Canadian Social Science, 9(1), 1-8. Available from: http://www. following terms used in the version must be complied; the cscanada.net/index.php/css/article/view/j.css.1923669720130901.1092 scope of the works must be permitted by the law and the DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3968/j.css.1923669720130901.1092. works should not be banned because of being criminal. These terms imply that other people will require author’s permission for compiling the work or for making a copy of his work. INTRODUCTION When it comes to the personal use of the work As it has been mandatory to mention the request of the or by the domestic-user version of the workbook author about his permission regarding reproduction of that is contained by the framework these conditions his work owing to prevent indictment traditions, and was are applicable only. -

A Proposal for Determining Substantial Similarity in Pop Music

DePaul Journal of Art, Technology & Intellectual Property Law Volume 16 Issue 2 Spring 2006 Article 3 No Justice for Johnson? A Proposal for Determining Substantial Similarity in Pop Music Jaime Walsh Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jatip Recommended Citation Jaime Walsh, No Justice for Johnson? A Proposal for Determining Substantial Similarity in Pop Music, 16 DePaul J. Art, Tech. & Intell. Prop. L. 261 (2006) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jatip/vol16/iss2/3 This Case Notes and Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Journal of Art, Technology & Intellectual Property Law by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walsh: No Justice for Johnson? A Proposal for Determining Substantial Si NO JUSTICE FOR JOHNSON? A PROPOSAL FOR DETERMINING SUBSTANTIAL SIMILARITY IN POP MUSIC I. INTRODUCTION Popular ("pop") music is one of the most recognizable and lucrative musical styles today, which makes it more likely to be the subject of infringement claims. Typically, an unknown songwriter claims infringement by alleging "that a popular, financially successful piece has been copied from his work" and that clearly "the defendant has stolen his masterpiece."' The accused infringer, however, "will allege that he has never heard the [songwriter's] composition and has independently composed his piece."2 Often composers believe their work has been copied due to the wide availability of pop music that gives the accused infringer easy access to the songwriter's work and because of the natural similarities that arise in this musical style. -

Penn Law: Legal Scholarship Repository Originality

University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School Penn Law: Legal Scholarship Repository Faculty Scholarship at Penn Law 3-5-2009 Originality Gideon Parchomovsky University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School Alex Stein Cardozo Law School & Yale Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Arts Management Commons, Economic Theory Commons, Intellectual Property Law Commons, Law and Economics Commons, Property Law and Real Estate Commons, Public Economics Commons, Social and Philosophical Foundations of Education Commons, and the Social Policy Commons Repository Citation Parchomovsky, Gideon and Stein, Alex, "Originality" (2009). Faculty Scholarship at Penn Law. 258. https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/faculty_scholarship/258 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Penn Law: Legal Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship at Penn Law by an authorized administrator of Penn Law: Legal Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PARCHOMOVSKY&STEIN_BOOK 9/17/2009 5:37 PM ORIGINALITY Gideon Parchomovsky* and Alex Stein** N this Article we introduce a model of copyright law that calibrates I authors’ rights and liabilities to the level of originality in their works. We advocate this model as a substitute for the extant regime that un- justly and inefficiently grants equal protection to all works satisfying the “modicum of creativity” standard. Under our model, highly original works will receive enhanced protection and their authors will also be sheltered from suits by owners of preexisting works. Conversely, au- thors of less original works will receive diminished protection and incur greater exposure to copyright liability.