The Renaissance of Sikh Devotional Music Memory, Identity, Orthopraxy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Note Staff Symbol Carnatic Name Hindustani Name Chakra Sa C

The Indian Scale & Comparison with Western Staff Notations: The vowel 'a' is pronounced as 'a' in 'father', the vowel 'i' as 'ee' in 'feet', in the Sa-Ri-Ga Scale In this scale, a high note (swara) will be indicated by a dot over it and a note in the lower octave will be indicated by a dot under it. Hindustani Chakra Note Staff Symbol Carnatic Name Name MulAadhar Sa C - Natural Shadaj Shadaj (Base of spine) Shuddha Swadhishthan ri D - flat Komal ri Rishabh (Genitals) Chatushruti Ri D - Natural Shudhh Ri Rishabh Sadharana Manipur ga E - Flat Komal ga Gandhara (Navel & Solar Antara Plexus) Ga E - Natural Shudhh Ga Gandhara Shudhh Shudhh Anahat Ma F - Natural Madhyam Madhyam (Heart) Tivra ma F - Sharp Prati Madhyam Madhyam Vishudhh Pa G - Natural Panchama Panchama (Throat) Shuddha Ajna dha A - Flat Komal Dhaivat Dhaivata (Third eye) Chatushruti Shudhh Dha A - Natural Dhaivata Dhaivat ni B - Flat Kaisiki Nishada Komal Nishad Sahsaar Ni B - Natural Kakali Nishada Shudhh Nishad (Crown of head) Så C - Natural Shadaja Shadaj Property of www.SarodSitar.com Copyright © 2010 Not to be copied or shared without permission. Short description of Few Popular Raags :: Sanskrut (Sanskrit) pronunciation is Raag and NOT Raga (Alphabetical) Aroha Timing Name of Raag (Karnataki Details Avroha Resemblance) Mood Vadi, Samvadi (Main Swaras) It is a old raag obtained by the combination of two raags, Ahiri Sa ri Ga Ma Pa Ga Ma Dha ni Så Ahir Bhairav Morning & Bhairav. It belongs to the Bhairav Thaat. Its first part (poorvang) has the Bhairav ang and the second part has kafi or Så ni Dha Pa Ma Ga ri Sa (Chakravaka) serious, devotional harpriya ang. -

MRIDANGA SYLLABUS for MA (CBCS) Effective from 2014-15

BANGALORE UNIVERSITY P.G. DEPARTMENT OF PERFORMING ARTS JNANABHARATHI, BANGALORE-560056 MRIDANGA SYLLABUS FOR M.A (CBCS) Effective from 2014-15 Dr. B.M. Jayashree. Professor of Music Chairperson, BOS (PG) M.A. MRIDANGA Semester scheme syllabus CBCS Scheme of Examination, continuous Evaluation and other Requirements: 1. ELIGIBILITY: A Degree music with Mridanga as one of the optional subject with at least 50% in the concerned optional subject an merit internal among these applicant Of A Graduate with minimum of 50% marks secured in the senior grade examination of Mridanga conducted by secondary education board of Karnataka OR a graduate with a minimum of 50% marks secured in PG Diploma or 2 years diploma or 4 year certificate course in Mridanga conducted either by any recognized Universities of any state out side Karnataka or central institution/Universities Any degree with: a) Any certificate course in Mridanga b) All India Radio/Doordarshan gradation c) Any diploma in Mridanga or five years of learning certificate by any veteran musician d) Entrance test (practical) is compulsory for admission. 2. M.A. Mridanga course consists of four semesters. 3. First semester will have three theory paper (core), three practical papers (core) and one practical paper (soft core). 4. Second semester will have three theory papers (core), three practical papers (core), one is project work/Dissertation practical paper and one is practical paper (soft core) 5. Third semester will have two theory papers (core), three practical papers (core) and one is open Elective Practical paper 6. Fourth semester will have two theory Papers (core) two practical papers (core), one project work and one is Elective paper. -

Presently Published Dasam Granth and British Connection; Guru Granth Sahib As the Only Sikh Canon

Presently Published Dasam Granth and British Connection; Guru Granth Sahib as the only sikh canon (From www.GlobalSikhStudies.net) Jasbir Singh Mann M.D., California. The lineage of Personal Guruship was terminated ( Canon Closed) on October, 6th Wednesday1708 A.D. by the 10th Guru, Guru Gobind Singh Ji, after finalizing the sanctification of Guru Nanak’s Mission and passing the succession to Guru Granth Sahib as future Guru of the Sikhs. This was the final culmination of the Sikh concept of Guruship, capable of resisting the temptation of continuation of the lineage of human Gurus. The Tenth Guru while maintaining the concept of ‘Shabad Guru’ also made the Panth distinctive by introducing corporate Guruship. The concept of Guruship continued and the role of human gurus was transferred to the Guru Panth and that of the revealed word to Guru Granth Sahib making Sikhism a unique modern religion. This historical fact is well documented in Indian, Persian and Western Sikh sources of 18th century. Indian sources: Sainapat (1711), Bhai Nand Lal, Bhai Prahlad, and Chaupa Singh, Koer Singh (1751), Kesar Singh Chhibber (1769-1779Ad), Mehama Prakash (1776), Munshi Sant Singh ( on account of Bedi family of the Ulna, Unpublished records), Bhatt Vahi’s. Persian sources: Mirza Muhammad (1705-1719 AD), Sayad Muhammad Qasim (1722 AD), Hussain Lahauri(1731), Royal Court News of Mughals, Akhbarat-i-Darbar-i-Mualla (1708). Western sources: Father Wendel, Charles Wilkins, Crauford, James Browne, George Forester, and John Griffith. These sources clearly emphasize the tenets of Nanak as enshrined in Guru Granth Sahib as the only promulgated scripture of the Sikhs. -

The Rich Heritage of Dhrupad Sangeet in Pushtimarg On

Copyright © 2006 www.vallabhkankroli.org - All Rights Reserved by Shree Vakpati Foundation - Baroda ||Shree DwaDwarrrrkeshokesho Jayati|| || Shree Vallabhadhish Vijayate || The Rich Heritage Of Dhrupad Sangeet in Pushtimarg on www.vallabhkankroli.org Reference : 8th Year Text Book of Pushtimargiya Patrachaar by Shree Vakpati Foundation - Baroda Inspiration: PPG 108 Shree Vrajeshkumar Maharajshri - Kankroli PPG 108 Shree Vagishkumar Bawashri - Kankroli Copyright © 2006 www.vallabhkankroli.org - All Rights Reserved by Shree Vakpati Foundation - Baroda Contents Meaning of Sangeet ........................................................................................................................... 4 Naad, Shruti and Swar ....................................................................................................................... 4 Definition of Raga.............................................................................................................................. 5 Rules for Defining Ragas................................................................................................................... 6 The Defining Elements in the Raga................................................................................................... 7 Vadi, Samvadi, Anuvadi, Vivadi [ Sonant, Consonant, Assonant, Dissonant] ................................ 8 Aroha, avaroha [Ascending, Descending] ......................................................................................... 8 Twelve Swaras of the Octave ........................................................................................................... -

India – Dera Sucha Sauda – Sikh – Congress

Country Advice India Dera Sucha Sauda – Sikh – Congress – 2007 clashes 8 December 2009 1 Please provide background information on Sikhs and the Dera Sacha Sauda sect. Is this a Sikh organization? The Dera Sacha Sauda (DSS) website provides information on the organisation stating that “Sacha Sauda is not a new religion, cult, sect or wave” instead is a “spiritual activity by which God is worshipped under the guidance of Satguru”: Sacha Sauda is not a new religion, cult, sect or wave. Sacha Sauda is that spiritual activity by which God is worshipped under the guidance of Satguru... Many saints and seers incarnated in this mortal world and inspired us to do this Sacha Sauda and became the guiding lights of spirtuality. These saints and seers were knowers of this supreme science and tried to make this mystical subject easy for the common man. One such torchbearer of spirituality was Beparwah Shah Mastana Ji Maharaj who did the most noble of services to mankind by establishing in1948 the spiritual college of Dera Sacha Sauda in order to save people from the complexities, malpractices and superficial rituals that had been afflicting religion and for the salvation of souls. 1 The website also outlines the organisation’s principles which indicate a progressive outlook respecting all religions equally and jettisoning certain orthodoxies and rituals. A former member of the sect is likely to have some knowledge of these principles: 1. In Dera Sacha Sauda all religions are equally honoured and welcomed. 2. Dera Sacha Sauda believes in humanity as the greatest religion and is involved in the true service of humanity. -

2020 03 19 O M.Pdf

file:///C:/Users/Admin/Desktop/HTML/2020_03_19_o_m.htm N O T E --------------------- The below mentioned cases will be listed in the Old Cases Cause list as per the dates so mentioned:- Sr. No. Case Details Party Details Advocate Name Listing Date 1. RSA-582-1989 (O&M) STATE OF PUNJAB AG PUNJAB, G.S DHILLON 19-MARCH-2020 V/S DASHMESH TRUCK BODY BUILDERS 2. RSA-1356-1989 (O&M) M/S RELIABLE AGRO K.K.MEHTA, O.P.HOSHIARPURI 19-MARCH-2020 ENGG. SERVICE PVT. LTD. V/S TARSEM SINGH 3. RSA-1600-1989 KEHAR SINGH V/S RAM ARUN JAIN,S S KAMBOJ,AVNISH 19-MARCH-2020 LUBHAYA MITTAL, DEEPAK ARORA,RAMAN WALIA, MAHESH GROVER 4. RSA-2334-1989 (O&M) KIRPAL KAUR V/S O.P.HOSHIARPURI, SARWAN SINGH 19-MARCH-2020 GURDIAL SINGH ETC. VIKAS WALIA, R.A. SHEORAN, , KARMINDER SINGH, RAJPAL, Y.K.SHARMA, , N S RAPRI 5. RSA-2440-1989 (O&M) BALWANT SINGH HEMANT KUMAR, A.K. AHLUWALIA 19-MARCH-2020 ETC. V/S DARSHOO @ K.L.MALHOTRA, VIPIN MAHAJAN, DARSHAN SINGH AMIT GUPTA. 6. RSA-904-1990 VINOD KUMAR AND OTHERS L.N. VERMA, S.P.LALLER, 19-MARCH-2020 V/S RAM PIARI AND B.S.CHAHAR, ASHOK VERMA, OTHERS 7. RSA-1060-1990 MUNSHI AND OTHERS JAI BHAGWAN TACORIA 19-MARCH-2020 V/S RAM SINGH B.R. MAHAJAN, K.S. KUNDU, RAJDEEP SINGH TACORIA ALL CONCERNED TO PLEASE NOTE. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- N O T E ----------------------- It is for the information of the all the Advocates/litigants that w.e.f.26.02.2020,in compliance of directions issued in RSA NO. -

Know Your Heritage Introductory Essays on Primary Sources of Sikhism

KNOW YOUR HERIGAGE INTRODUCTORY ESSAYS ON PRIMARY SOURCES OF SIKHISM INSTITUTE OF S IKH S TUDIES , C HANDIGARH KNOW YOUR HERITAGE INTRODUCTORY ESSAYS ON PRIMARY SOURCES OF SIKHISM Dr Dharam Singh Prof Kulwant Singh INSTITUTE OF S IKH S TUDIES CHANDIGARH Know Your Heritage – Introductory Essays on Primary Sikh Sources by Prof Dharam Singh & Prof Kulwant Singh ISBN: 81-85815-39-9 All rights are reserved First Edition: 2017 Copies: 1100 Price: Rs. 400/- Published by Institute of Sikh Studies Gurdwara Singh Sabha, Kanthala, Indl Area Phase II Chandigarh -160 002 (India). Printed at Adarsh Publication, Sector 92, Mohali Contents Foreword – Dr Kirpal Singh 7 Introduction 9 Sri Guru Granth Sahib – Dr Dharam Singh 33 Vars and Kabit Swiyyas of Bhai Gurdas – Prof Kulwant Singh 72 Janamsakhis Literature – Prof Kulwant Singh 109 Sri Gur Sobha – Prof Kulwant Singh 138 Gurbilas Literature – Dr Dharam Singh 173 Bansavalinama Dasan Patshahian Ka – Dr Dharam Singh 209 Mehma Prakash – Dr Dharam Singh 233 Sri Gur Panth Parkash – Prof Kulwant Singh 257 Sri Gur Partap Suraj Granth – Prof Kulwant Singh 288 Rehatnamas – Dr Dharam Singh 305 Know your Heritage 6 Know your Heritage FOREWORD Despite the widespread sweep of globalization making the entire world a global village, its different constituent countries and nations continue to retain, follow and promote their respective religious, cultural and civilizational heritage. Each one of them endeavours to preserve their distinctive identity and take pains to imbibe and inculcate its religio- cultural attributes in their younger generations, so that they continue to remain firmly attached to their roots even while assimilating the modern technology’s influence and peripheral lifestyle mannerisms of the new age. -

The Doctrinal Inconsistencies in Dasam Granth : in Relation to Avtarhood(Part I)

The Doctrinal inconsistencies in Dasam Granth : In relation to Avtarhood(Part I) Prof.Gurnam Kaur* (A) Introduction:- This paper is concerned with the authenticity of the compositions included in the Dasam Granth or we can say with the doctrinal inconsistencies in the Dasam Granth in relation to the idea of avtarhood,i.e. incarnation of God in different forms human or any, devi pooja (worship of goddess) shastar as Pir i.e. to worship weapons as the highest spiritual person, bias against unshorn hair, supporting the use of intoxicants and bias against woman. To judge all these things we have to take the help of Sikh tenants and adopt some basic criterion or methodology because these days animated discussions are going on about the Dasam Granth. The text has already been analyzed by known scholars from the historical, religious and theological points of view. Being the student of Sikh philosophy, with due regards to the analysis already done, I will try to analyze the text in the light of Sri Guru Granth Sahib. Sri Guru Granth Sahib is the basic and primary scripture of Sikh religion. No other scripture can be considered equal to it. This is the only Scripture in the history of the world religions which was compiled by its founder Gurus themselves. The fifth Guru Arjan Dev compiled the first recension and installed it at Harmander Sahib on Bhadon sudi. I, 1604 A.D. Bhai Gurdas was the first scribe and Baba Budha Ji was made the first Granthi. Guru Gobind Singh, the Tenth and last physical Guru, added the bani composed by Guru Teg Bahadur, the ninth Nanak Joti and bestowed 1 Guruship on the Granth before his final departure in samat 1765 from this mundane world. -

6. ADDITIONAL SUBJECTS (A) MUSIC Any One of the Following Can Be Offered: (Hindustani Or Carnatic)

6. ADDITIONAL SUBJECTS (A) MUSIC Any one of the following can be offered: (Hindustani or Carnatic) 1. Carnatic Music-Vocal 4. Hindustani Music-Vocal or or 2. Carnatic Music-Melodic Instruments 5. Hindustani Music Melodic Instruments or or 3. Carnatic Music-Percussion 6. Hindustani Music Percussion Instruments Instruments (i) CARNATIC MUSIC VOCAL THE WEIGHTAGE FOR FORMATIVE ASSESSMENT (F.A.) AND SUMMATIVE ASSESSMENT (S.A.) FOR TERM I & II SHALL BE AS FOLLOWS Term Type of Assessment Percentage of Termwise Total Weightage in Weightage Academic Session for both Terms First Term Summative 1 15% 15+35 50% (April - Theory Paper Sept.) Practicals 35% Second Summative 2 15% 15+35 50% Term Theory Paper (Oct.- Practicals 35% March) Total 100% Term-I Term-II Total Theory 15% + 15% = 30% Practical 35% + 35% = 70% Total 100% 163 Carnatic Music (Code No. 034) Any one of the following can be offered : (Hindustani or Carnatic) 1. Carnatic Music-Vocal 4. Hindustani Music-Vocal or or 2. Carnatic Music-Melodic Instruments 5. Hindustani Music Melodic Instruments or or 3. Carnatic Music-Percussion 6. Hindustani Music Percussion Instruments Instruments (i) CARNATIC MUSIC VOCAL THE WEIGHTAGE FOR FORMATIVE ASSESSMENT (F.A.) AND SUMMATIVE ASSESSMENT (S.A.) FOR TERM I & II SHALL BE AS FOLLOWS Term Type of Assessment Percentage of Termwise Total Weightage in Weightage Academic Session for both Terms First Term Summative 1 15% 15+35 50% (April - Theory Paper Sept.) Practicals 35% Second Summative 2 15% 15+35 50% Term Theory Paper (Oct.- Practicals 35% March) Total 100% Term-I Term-II Total Theory 15% + 15% = 30% Practical 35% + 35% = 70% Total 100% 164 SYLLABUS FOR SUMMATIVE ASSESSMENT FIRST TERM (APRIL 2016 - SEPTEMBER 2016) CARNATIC MUSIC (VOCAL) (CODE 031) CLASS IX TOPIC (A) Theory 15 Marks 1. -

![Life Story of Sant Attar Singh Ji [Of Mastuana Sahib]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9856/life-story-of-sant-attar-singh-ji-of-mastuana-sahib-679856.webp)

Life Story of Sant Attar Singh Ji [Of Mastuana Sahib]

By the same author : 1. Sacred Nitnem -Translation & Transliteration 2. Sacred Sukhmani - Translation & Transliteration 3. Sacred Asa di Var - Translation & Transliteration 4. Sacred Jap Ji - Translation & Transliteration 5. Life, Hymns and Teachings of Sri Guru Tegh Bahadur Ji 6. Stories of the Sikh Saints "'·· 7. Sacred Dialogues of Sri Guru Nanak Dev Ji 8. Philosophy of Sikh Religion (God, Maya and Death) 9. Life Story of Guru Gobind Singh Ji & His Hymns 10. Life Story of Guru Nanak Dev Ji & Bara-Maha 11. Life Story of Guru Amardas Ji ,, 12. Life Story of Bhagat Namdev Ji & His Hymns t' 13. How to See God ? 14. Divine Laws of Sikh Religion (2 Parts) L' LIFE STORY OF SANT ATTAR SINGH JI [OF MASTUANA SAHIB] HARBANS SINGH DOABIA SINGH BROS. AMRITSAR LIFE STORY OF SANT ATTAR SINGH JI by HARBANS SINGH OOABIA © Author ISBN 81-7205-072-0 First Edition July 1992 Second Edition September 1999 Price : Rs. 60-00 Publishers : SINGH BROTHERS, BAZAR MAI SEWAN, AMRITSAR. Printers: PRINTWELL, 146, INDUSTRIAL FOCAL POINT, AMRITSAR. CONTENTS -Preface 7 I The Birth and Childhood 11 II Joined Army-Left for Hazur Sahib without leave 12 III Visited Hardwar and other places 16 IV Discharge from Army-Then visited many places-Performed very long meditations 18 V Some True Stories of that pedod 24 VI Visited Rawalpindi and other places 33 VII Visited Lahore and Sindh and other places 51 VIII Stay at Delhi-Then went to Tam Tarm and Damdama Sahib 57 IX Visit to Peshawar, Kohat etc. and other stories 62 X Visit to Srinagar-Meeting with Bhai Kahan Singh of Nabha- -

Diploma in Gurmat Sangeet

DIPLOMA IN GURMAT SANGEET ACADEMIC POLICY/ORDINANCES Objectives of the Course : An Online initiative by Gurmat Sangeet Chair - Department of Gurmat Sangeet, Punjabi University, Patiala to disseminate the message of Sikh Gurus through Gurmukhi, Gurmat Studies and Gurmat Sangeet at global level. Duration of the Course : Two Semester Eligibility : The candidate must have passed Certificate Course in Gurmat Sangeet in the same stream Medium of Instruction : English & Punjabi Medium of Examination : English & Punjabi Fees for the Course : On admission in the course a candidate shall have to pay Admission fees (including Examination Fee) as given below Admission Fee : 300US$ (15,000/- INR) upto 30th June st With Late Fee 350US$ (17,500/- INR) upto 31 July With Late Fee 450US$ (22,500/- INR) and with the st special permission of Vice Chancellor upto 31 August SCHEME OF THE COURSE FOR SPRING SEMESTER Compulsory/ Papers Paper Code Title of the Papers Elective Compulsory Paper I DGS 301 Historical Study of Sikhism Papers Paper III DGS 302 Gurbani Santhya DGS 303 Musicology of Gurmat Sangeet Vocal Tradition Elective Paper II DGS 304 Musicology of Gurmat Sangeet String Instrumental Tradition Papers DGS 305 Musicology of Gurmat Sangeet Percussion Instrumental Tradition (Jorhi/Tabla) DGS 306 Stage Performance of Shabad Keertan Elective Paper IV DGS 307 Stage Performance of String Instruments Papers DGS 308 Stage Performance of Percussion Instrumental (Jorhi/Tabla) 1 HISTORICAL STUDY OF SIKHISM (Paper I - DGS 301) 1. Contribution of Ten Guru in Propagation of Sikhism 2. Contributors of Bhai Mardana ji, Baaba Budha ji, Bhai Gurdas ji, and Bhai Nand lal ji in Sikh History. -

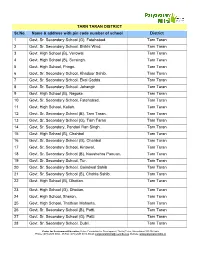

TARN TARAN DISTRICT Sr.No. Name & Address With

TARN TARAN DISTRICT Sr.No. Name & address with pin code number of school District 1 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Fatehabad. Tarn Taran 2 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Bhikhi Wind. Tarn Taran 3 Govt. High School (B), Verowal. Tarn Taran 4 Govt. High School (B), Sursingh. Tarn Taran 5 Govt. High School, Pringri. Tarn Taran 6 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Khadoor Sahib. Tarn Taran 7 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Ekal Gadda. Tarn Taran 8 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Jahangir Tarn Taran 9 Govt. High School (B), Nagoke. Tarn Taran 10 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Fatehabad. Tarn Taran 11 Govt. High School, Kallah. Tarn Taran 12 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Tarn Taran. Tarn Taran 13 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Tarn Taran Tarn Taran 14 Govt. Sr. Secondary, Pandori Ran Singh. Tarn Taran 15 Govt. High School (B), Chahbal Tarn Taran 16 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Chahbal Tarn Taran 17 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Kirtowal. Tarn Taran 18 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Naushehra Panuan. Tarn Taran 19 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Tur. Tarn Taran 20 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Goindwal Sahib Tarn Taran 21 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Chohla Sahib. Tarn Taran 22 Govt. High School (B), Dhotian. Tarn Taran 23 Govt. High School (G), Dhotian. Tarn Taran 24 Govt. High School, Sheron. Tarn Taran 25 Govt. High School, Thathian Mahanta. Tarn Taran 26 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Patti. Tarn Taran 27 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Patti. Tarn Taran 28 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Dubli. Tarn Taran Centre for Environment Education, Nehru Foundation for Development, Thaltej Tekra, Ahmedabad 380 054 India Phone: (079) 2685 8002 - 05 Fax: (079) 2685 8010, Email: [email protected], Website: www.paryavaranmitra.in 29 Govt.