The Myth of the Messenger Jules Cashford

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Greek Origin of Caduceum: Æsculapius

Colombia Médica Vol. 39 Nº 4, 2008 (Octubre-Diciembre) The Greek origin of caduceum: Æsculapius ARTURO G. RILLO, DR EN H* SUMMARY Introduction: Medicine history gives us the chance to reflect about the Caduceus as the synthesis of the dialectic of the sensible and spiritual life. This opens and horizon of comprehension and allow us to recover the legend of Asclepius and it’s cult with the different symbolic elements that structure it. The legend: The historic and mythological references about Asclepius’ existence gives structure to the legend in a real and not-real environment perduring in the occidental medicine tradition as a mystical reference to the deity for the medical practice. The cult: It’s based in the incubation and synthesizes healing rites and therapeutical practices, as medical as surgical; exercise, sleep cures and amusement activities. The symbol: The linguistic origin of Asclepius’ name, the symbolism of the legend protagonists and the iconographic representation of their attributes, converge in the Caduceus to represent the medical practices and ideas synthesis, all them related to the human life. Conclusion: Asclepius’ perception transcends the Olympic divinity and situates him as the healing archetype; that’s why Caduceus is consistent with the system-world representation that rules the actual medical practice. Keywords: Caduceum; Æsculapius; Æsclepius; History of medicine; Philosophy of medicine. El origen griego del caduceo: Esculapio RESUMEN Introducción: La historia de la medicina posibilita reflexionar sobre el caduceo como la síntesis de la dialéctica de la vida sensible y la espiritual. Esto abre un horizonte de comprensión y permite recuperar la leyenda de Esculapio y su culto con los diferentes elementos simbólicos que la componen. -

Greek Mythology

Greek mythology Mythical characters Gods and goddesses Zeus is the king of the gods, ruler of Mount Olympus and god of the sky. His name means ‘bright’ or ‘sky’. His royal animals are the eagle and bull. Zeus’s favourite weapon is a lightning bolt made for him by the Cyclops. Zeus can be a greedy and dishonest god. If he desires something, he is unlikely to let anything stop him from gaining it. Because of this, he often lies about his behaviour to Hera, his wife. Hera is the queen of the gods and wife of Zeus. She is the goddess of women, marriage, childbirth, heirs, kings and empires. She often carries a lotus- tipped staff. Hera never forgets an insult or injury and can be cruel or vengeful. Poseidon is the god of rivers, seas, floods, droughts and earthquakes. Brother to Zeus, he is the king of the sea and protector of all waters. Poseidon carries a trident: a spear with three points. His sacred animals are the dolphin and the horse. Athena is the goddess of wisdom, intelligence, skill, peace and warfare. According to legend, she was born out of Zeus’s forehead fully formed and fully armoured. She looks over heroes such as Odysseus and Hercules. Athena is often accompanied by a sacred owl. Her symbol is the olive tree. KS2 | Page 1 copyright 2019 Greek mythology Gods and goddesses Aphrodite is the goddess of love and beauty, who can cause gods or mortals to fall in love with whomever she chooses. Aphrodite’s sacred animals include doves and sparrows. -

FAVORITE GREEK MYTHS VARVAKEION STATUETTE Antique Copy of the Athena of Phidias National Museum, Athens FAVORITE GREEK MYTHS

FAVORITE GREEK MYTHS VARVAKEION STATUETTE Antique copy of the Athena of Phidias National Museum, Athens FAVORITE GREEK MYTHS BY LILIAN STOUGHTON HYDE YESTERDAY’S CLASSICS CHAPEL HILL, NORTH CAROLINA Cover and arrangement © 2008 Yesterday’s Classics, LLC. Th is edition, fi rst published in 2008 by Yesterday’s Classics, an imprint of Yesterday’s Classics, LLC, is an unabridged republication of the work originally published by D. C. Heath and Company in 1904. For the complete listing of the books that are published by Yesterday’s Classics, please visit www.yesterdaysclassics.com. Yesterday’s Classics is the publishing arm of the Baldwin Online Children’s Literature Project which presents the complete text of hundreds of classic books for children at www.mainlesson.com. ISBN-10: 1-59915-261-4 ISBN-13: 978-1-59915-261-5 Yesterday’s Classics, LLC PO Box 3418 Chapel Hill, NC 27515 PREFACE In the preparation of this book, the aim has been to present in a manner suited to young readers the Greek myths that have been world favorites through the centuries, and that have in some measure exercised a formative infl uence on literature and the fi ne arts in many countries. While a knowledge of these myths is undoubtedly necessary to a clear understanding of much in literature and the arts, yet it is not for this reason alone that they have been selected; the myths that have appealed to the poets, the painters, and the sculptors for so many ages are the very ones that have the greatest depth of meaning, and that are the most beautiful and the best worth telling. -

Venus Anadyomene: the Mythological Symbolism from Antiquity to the 19Th Century

VENUS ANADYOMENE: THE MYTHOLOGICAL SYMBOLISM FROM ANTIQUITY TO THE 19TH CENTURY By Jenna Marie Newberry A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN ART HISTORY University of Wisconsin – Superior December 2011 2 3 Title: Venus Anadyomene: The Mythological Symbolism from Antiquity to the 19th Century Author: Newberry, Jenna Marie Advisors: Famule, Olawole and Morgan, William Abstract: This thesis includes reading the chosen artworks as a visual interpretation of the written mythological birth of Venus by the sea. Reading the selected painting as visual novels, the pictorial symbolism helps prove or disprove the true theme of the Venus. The writer bases her theory on the inclusion of mythological symbols that represent the Venus Anadyomene; scallop shell, dolphins, Aros, dove, sparrow, girdle, mirror, myrtle, and roses. The comparison of various artists‟ interpretations of this theme and the symbols they use to recognize the Venus as such is a substantial part of the research. The writer concludes in this thesis that the chosen art pieces are or are not a Venus Anadyomene, and in fact just a female nude entitled and themed fallaciously for an allure or ambiance. Through extensive research in the mythological symbolism of the Goddess of Love, the above-mentioned symbols used by various artists across several eras prove the Venus a true character of mythological history. Description: Thesis (M.A.) – University of Wisconsin, Superior, 2011. 30 leaves. 4 CONTENTS TITLE -

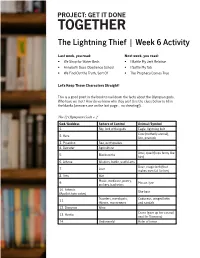

The Lightning Thief | Week 6 Activity

The Lightning Thief | Week 6 Activity Last week, you read: Next week, you read: • We Shop for Water Beds • I Battle My Jerk Relative • Annabeth Does Obedience School • I Settle My Tab • We Find Out the Truth, Sort Of • The Prophecy Comes True Let’s Keep These Characters Straight! This is a good point in the book to nail down the facts about the Olympian gods. Who have we met? How do we know who they are? Use the clues below to fill in the blanks (answers are on the last page… no cheating!). The 12 Olympian Gods + 2 God/Goddess Sphere of Control Animal/Symbol 1. Sky, lord of the gods Eagle, lightning bolt Cow (motherly animal), 2. Hera lion, peacock 3. Poseidon Sea, earthquakes 4. Demeter Agriculture Anvil, quail (hops funny like 5. Blacksmiths him) 6. Athena Wisdom, battle, useful arts Dove, magic belt (that 7. Love makes men fall for her) 8. Ares War Music, medicine, poetry, 9. Mouse, lyre archery, bachelors 10. Artemis She-bear (Apollo’s twin sister) Travelers, merchants, Caduceus, winged helm 11. thieves, messengers and sandals 12. Dionysus Wine Crane (gave up her council 13. Hestia seat for Dionysus) 14. Underworld Helm of terror The Lightning Thief | Week 6 Activity Your New Neighborhood: Elysium Look through magazines or the internet for pictures of beautiful houses you’d like to live in. Make a collage of what you image Elysium looks like. The Lightning Thief | Week 6 Activity Answers God/Goddess Sphere of Control Animal/Symbol 1. Zeus Sky, lord of the gods Eagle, lightning bolt Cow (motherly animal), 2. -

A Lifetime of Trouble-Mai(Ing: Hermes As Trici(Ster

FOUR A LIFETIME OF TROUBLE-MAI(ING: HERMES AS TRICI(STER William G. Doty In exploring here some of the many ways the ancient Greek figure of Hermes was represented we sight some of the recurring characteristics of tricksters from a number of cultures. Although the Hermes figure is so complex that a whole catalog of his characteristics could be presented,1 the sections of this account include just six: (1) his marginality and paradoxical qualities; (2) his erotic and relational aspects; (3) his func tions as a creator and restorer; (4) his deceitful thievery; (5) his comedy and wit; and (6) the role ascribed to him in hermeneutics, the art of interpretation whose name is said to be derived from his. The sixth element listed names one of the most significant ways this trickster comes to us-as interpreter, messenger-but the other characteristics we will explore provide important contexts for what is conveyed, and how. This is not just any Western Union or Federal Express worker, but a marginal figure whose connective tasks shade over into creativity itself. A hilarious cheat, he sits nonetheless at the golden tables of the deities. We now recognize that even apparently irreverent stories show that some mythical models could be conceived in a wide range of sig nificances, even satirized, without thereby abandoning the meaning complex in which the models originated. For example an extract from a satire by Lucian demonstrates that Hermes could be recalled with re Copyright © 1993. University of Alabama Press. All rights reserved. of Alabama Press. © 1993. University Copyright spect, as well as an ironic chuckle: Mythical Trickster Figures You :are Contours, reading Contexts, copyrighted and material Criticisms, published edited by Williamthe University J. -

The Staff of Asclepius Or Hermes Eric Vanderhooft, M.D

aduceus Cthe staff of Asclepius or Hermes Eric Vanderhooft, M.D. The author (AΩA, University of Utah, 1988) is clinical assistant professor in the Department of Orthopedics at the University of Utah, and in private practice at the Salt Lake Orthopedic Clinic. He is also the clinical director of the University Orthopedic Rotation and Family Practice Residency Orthopedic Rotation at HCA St. Mark’s Hospital. he staff entwined by a serpent or serpents is ac- cepted as a common symbol of the medical pro- fession and health care industry. Unfortunately, twoT distinct images exist. The staff with a single snake be- longed to Asclepius, father of western medicine. The staff with two entwined snakes belonged to Hermes, the prince of thieves, and is more commonly seen. A review of 527 professional medical academies, asso- ciations, colleges, and societies revealed that 23 organiza- tions use the staff in their symbolism. The staff of Asclepius outnumbered that of Hermes nearly three-fold, 92 versus 3 organizations respectively. Introduction Hippocrates has come to be considered the father of Western medicine, and, in the United States, a modification of the Hippocratic Oath continues to be recited by graduat- ing medical students. It should therefore be no surprise that Roman statue of Asclepius. © Mimmo Jodice/CORBIS. The Pharos/Autumn 2004 our symbol for medicine, the caduceus, similarly is derived from Greek traditions. Greek healers such as Hippocrates be- lieved they were descended from Asclepius, the mythic phy- sician, and came to be known as Asklepiadai or Asclepiads, “sons of Asclepius.”1p6 Represented variously by the snake, cock, dog, and goat,1p28–32, 2, 3p258 the staff entwined by a single snake is the most recognized symbol of Asclepius. -

Mythology, Greek, Roman Allusions

Advanced Placement Tool Box Mythological Allusions –Classical (Greek), Roman, Norse – a short reference • Achilles –the greatest warrior on the Greek side in the Trojan war whose mother tried to make immortal when as an infant she bathed him in magical river, but the heel by which she held him remained vulnerable. • Adonis –an extremely beautiful boy who was loved by Aphrodite, the goddess of love. By extension, an “Adonis” is any handsome young man. • Aeneas –a famous warrior, a leader in the Trojan War on the Trojan side; hero of the Aeneid by Virgil. Because he carried his elderly father out of the ruined city of Troy on his back, Aeneas represents filial devotion and duty. The doomed love of Aeneas and Dido has been a source for artistic creation since ancient times. • Aeolus –god of the winds, ruler of a floating island, who extends hospitality to Odysseus on his long trip home • Agamemnon –The king who led the Greeks against Troy. To gain favorable wind for the Greek sailing fleet to Troy, he sacrificed his daughter Iphigenia to the goddess Artemis, and so came under a curse. After he returned home victorious, he was murdered by his wife Clytemnestra, and her lover, Aegisthus. • Ajax –a Greek warrior in the Trojan War who is described as being of colossal stature, second only to Achilles in courage and strength. He was however slow witted and excessively proud. • Amazons –a nation of warrior women. The Amazons burned off their right breasts so that they could use a bow and arrow more efficiently in war. -

The-Palace-Of-Olympus.Pdf

The Palace of Olympus god, and Queen Hera, the Mother-goddess. The northern end of the palace, looking across the valley of Tempe towards the wild hills of Macedonia, consisted of the kitchen, Home of the banqueting hall, armory, workshops, and gods and goddesses servants’ quarters. In between came a Ancient square court, open to the sky, with covered Greece cloisters and private rooms on each side, belonging to the other five Olympian gods and the other five Olympian goddesses. Beyond the kitchen and servants’ quarters stood cottages for smaller gods, sheds for chariots, stables for horses, kennels for hounds, and a sort of zoo where the Olympians kept their sacred animals. These included a bear, a lion, a peacock, an eagle, tigers, stags, a cow, a crane, snakes, a wild boar, white bulls, a wild cat, mice, swans, herons, an owl, a tortoise, and a tank full of fish. In the Council Hall the Olympians met at times to discuss mortal affairs – such as which army on earth should be allowed to win a war, and whether they ought to punish some king or queen who had been behaving proudly or disgustingly. But for the most part they were too busy with their own quarrels The TWELVE most important gods and lawsuits to take much notice of mortal and goddesses of ancient Greece, called the affairs. King Zeus had an enormous throne Olympians, belonged to the same large, of polished black Egyptian marble, decorated quarrelsome family. Though thinking little of in gold. Seven steps led up to it, each of the smaller, old-fashioned gods over whom them enameled with one of the seven colors they ruled, they thought even less of mortals. -

Lecture 20 Good Morning and Welcome to LLT121, Classical Mythology

Lecture 20 Good morning and welcome to LLT121, Classical Mythology. As promised, today we will be discussing the careers of two deities, Athena and Hermes, who are of primary interest, not so much because of what they’re in charge of—although they are in charge of some important things. Neither one of them has a tremendous amount of mythology, so to speak. These two deities figure more in other god’s and goddess’s myths, other hero’s myths, than their own. There’s maybe about two or three good stories, tops, about each one. However, Athena, for example—and we can begin with Athena—since she is the patron goddess of the award winning city of Athens, she shows up in just about every story that is written by an Athenian. Let’s take some examples here. The Athena story starts out when Zeus, supposedly, is married to Metis. Metis is the ancient Greek word for “thought.” Metis is, obviously, an only vaguely anthropomorphic personification goddess of thought. It makes sense, doesn’t it, that Zeus gets married to thought? Thought is not going to get married to Hades or Poseidon or any of these other lunatics. But Zeus finds out, by means of an oracle, a handy oracle, that Metis is going to give birth to two children. One is the goddess Athena and two is a son who will grow up to be greater than his father. As you’ll recall from our discussion of cosmogony, the supreme gods are always having to deal with the notion of raising a son who’s going to be stronger than you. -

Brother G's Cyclopedia

Brother G’s Cyclopedia Of Comparative Mythology 210 building blocks for the aspiring mythopoet B c d e f g h k l m t u Dedicated To Messrs. Mircea Eliade and Hugh Nibley, who introduced a young boy to comparative mythology. To Lord Dunsany and Mr. H. P. Lovecraft, who pioneered the art of literary mythopoeia. And To Messrs. M. A. R. Barker and J. R. R. Tolkien, who taught us that master worldbuilders must be referred to by three initials and a last name. Table of Contents Introduction…………………………………………………………………...................................1 From Acosmism to Writing ………………………………………………………………….....x Appendix A: Non-Standard Portfolios………………………………………………………...x Appendix B: Epithets and Fusions……………………………………………………………..x Appendix C: Meta-Theory…………………………………………………………………......... x Appendix D: Story-starting Phrases…………………………………………………………… x Appendix E: Bringing It Together……………………………………………………………… x Appendix F: Random Tables…………………………………………………………………... x 1 Introduction Appendix A: Appendix B: Appendix C: If the main entry concerns itself chiefly with ideas of religion and mythology, then Appendix C concerns itself chiefly with ideas about religion and mythology. Appendix D: Appendix E: Appendix F: Include reading list 2 A solar vehicle is a mode of transportation used by the sun to make its journey across the sky and anywhere else that it goes (such as the underworld). It is most commonly a barge or chariot. Depictions of solar barges date to the Neolithic and are older than the sun chariot. Examples include the solar barge of Ra (Egyptian) and the chariots of Apollo (Greek) and Surya (Hindu). A world tree is an AXIS MUNDI. Typically its roots reach the UNDERWORLD (represented as either earth or water) and its branches (inhabited by birds) the OVERWORLD in order to connect them to each other and to the phenomenal world. -

Asclepius, Caduceus, and Simurgh As Medical Symbols Part I Touraj Nayernouri MD FRCS•*

Arch Iran Med 2010; 13 (1): 61 – 68 History of Medicine Asclepius, Caduceus, and Simurgh as Medical Symbols Part I Touraj Nayernouri MD FRCS•* Abstract the sight of a serpent evokes in the perceiving This is the first of two articles reviewing the history mind is well documented even in non human of medical symbols. In this first article I have briefly primates.1 reviewed the evolution of the Greek god, Asclepius, The reason that such an awesome apparition (and his Roman counterpart Aesculapius) with the single serpent entwined around a wooden rod as a should be associated with the art of healing is symbol of western medicine and have alluded to the perhaps lost within the mists of human mythopoeia misplaced adoption of the Caduceus of the Greek and is outwith the scope of this essay, but some god Hermes (and his Roman counterpart Mercury) historical connections might be useful in order to with its double entwined serpents as an alternative shed light on some aspects of this symbolism. symbol. In the second part of this article (to be published later), I have made a tentative suggestion of why the Ancient symbolism Simorgh might be adopted as an Eastern or an Asian One of the oldest known associations of the symbol for medicine. serpent with healing and magic is a depiction of Keywords: Asclepius ● Caduceus ● medical the ancient Sumerian fertility god, Ningizzida, who symbols ● Simurgh later became a god of healing, represented by two snakes entwined around a rod accompanied by two Introduction gryphons (Figure 1). ymbols are powerful representational Similar images of gryphons and two coiled tools in the evolution of cultures, and in snakes carved on a marble vase have been found Sthe history of medicine, few have recently in Jiroft, south eastern Iran, dated to mid survived the vicissitudes of time and the changing third century BCE which at present lacks fashions, except the image of the serpent.