Poetry Winner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contributors

Contributors Andres Ajens is a Chilean poet, essayist, and translator. His latest works include /E (Das Kapital, 2015) and Bolivian Sea (Flying Island, 2015). He co-directs lntemperie Ediciones (www.intemperie. cl) and Mar con Soroche (www.intemperie.cl/soroche.htm). In English: quase ftanders, quase extramadura, translated by Erin Moure from Mas intimas mistura (La Mano Izquierda, 2008), and Poetry After the Invention ofAmerica: D on't L ight the Flower, translated by Michelle Gil-Montero (Palgrave Macmillan, 2011). Mike Borkent holds a doctorate from and teaches at the University of British Columbia. His research focuses on cognitive approaches to multimodal literatures, focusing on North American visual poetry and graphic narratives. He recently co-edited the volume Language and the Creative Mind (CSLI 2013) with Barbara Dancygier and Jennifer Hinnell, and has authored several articles and reviews on poetry, comics, and criticism. He was also the head developer and co-author of CanLit Guides (www. canlitguides.ca) for the journal Canadian L iterature (2011-14). Hailing from Africadia (Black Nova Scotia), George Elliott Clarke is a founder of the field of African-Canadian literature. Revered as a poet, he is currently the (4th) Poet Laureate of T oronto (2012-15). The poems appearing here are from his epic, "Canticles," due out in November 2016 from Guernica Editions. Ruth Cuthand was born in Prince Albert and grew up in various communities throughout Alberta and Saskatchewan. With her Plains Cree heritage, Cuthand's practice explores the frictions between cultures, the failures of representation, and the political uses of anger. Her mid-career retrospective exhibition, Back Talk, curated by Jen Budney from the Mendel Art Gallery in Saskatoon, has been touring Canada since 2011. -

MUSIC-MUSIC-LIFE Online Adam Seelig One Little Goat-Lowres

MUSIC MUSIC LIFE DEATH MUSIC MUSIC MUSIC LIFE DEATH MUSIC AN ABSURDICAL ADAM SEELIG copyright © Adam Seelig, 2018 first edition ALL RIGHTS RESERVED No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. This play is protected under the copyright laws of Canada and all other countries of the Copyright Union. Rights to produce, perform, film, record or publish in any medium, in an language, by any group are retained by the author. For all performance rights—be they for text, music, or both—please contact One Little Goat Theatre Company, 422 Brunswick Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, M5R 2Z4, Canada. Phone 416 915 0201; [email protected]; www.onelit- tlegoat.org Issued in print and electronic formats ISBN 978-1-7753255-0-5 (pbk) ISBN 978-1-7753255-1-2 (pdf) Text + Design: Norman Nehmetallah Cover Design: Kilby Smith-McGregor Cover Photo: Yuri Dojc Cover Photo, L to R: Jennifer Villaverde, Theresa Tova, Richard Harte, Sierra Holder Music and Lyrics: Adam Seelig Music Transcription: Tyler Emond Printed in Ontario In memory of Jory Groberman (1975-2016) lifelong friend PRODUCTION HISTORY MUSIC MUSIC LIFE DEATH MUSIC: An Absurdical premiered at the Tarragon Theatre Extra Space in Toronto, May 25-June 10, 2018 in a One Little Goat Theatre Company production directed by Adam Seelig. CAST DD Jennifer Villaverde JJ Richard Harte B / Baba Theresa Tova PP Sierra -

A (Mini) History of Theatre for Kids Adam Seelig

PLAY A (MINI) HISTORY OF THEATRE FOR KIDS ADAM SEELIG copyright © Adam Seelig, 2019 first edition ALL RIGHTS RESERVED No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. This play is protected under the copyright laws of Canada and all other countries of the Copyright Union. Rights to produce, perform, film, record or publish in any medium, in an lan- guage, by any group are retained by the author. For all performance rights (be they for text, music, or both) please contact One Little Goat Theatre Company, 422 Brunswick Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, M5R 2Z4, Canada. Phone 416 915 0201; [email protected]; www.onelittlegoat.org Issued in print and electronic formats ISBN 978-1-7753255-2-9 (pbk) ISBN 978-1-7753255-3-6 (pdf) Text + Design: Norman Nehmetallah Printed at the Coach House on bpNichol Lane in Toronto, Ontario on Zephyr Antique Laid paper, which was manufactured, acid-free, in Saint Jérôme, Quebec, from second-growth forests. for Shai and Arlo with love and love PRODUCTION HISTORY PLAY: A (Mini) History of Theatre for Kids was first performed at the Paul Penna Downtown Jewish Day School in Toronto on November 2, 2015, in a One Little Goat Theatre Company pro- duction directed by Adam Seelig. Since then, it has been performed for thousands of children in elementary schools throughout Toronto. CAST A Richard Harte M Rochelle Bulmer alternating with Jessica Salgueiro PRODUCTION Set & Costume Designer Jackie Chau Stage Manager Sam Hale 4 CAST A a person (male in this text – can be played by anyone) M Mavis-the-Sometimes-Cat and others (female in this text – can be played by anyone) DEAR ACTORS Pace and emphasize the text as you and director wish. -

Universidade Federal Do Rio Grande Do Sul Instituto De Letras Programa De Pós-Graduação Literaturas Estrangeiras Modernas Literaturas De Lingua Inglesa

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO SUL INSTITUTO DE LETRAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO LITERATURAS ESTRANGEIRAS MODERNAS LITERATURAS DE LINGUA INGLESA ANA LÚCIA MONTANO BOESSIO AMONGST SHADOWS AND LABYRINTHS A VISUAL POETICS FOR SAMUEL BECKETT’S OHIO IMPROMPTU Tese de Doutorado em Literaturas de Língua Inglesa Para a obtenção do título de Doutor em Letras Ubiratan Paiva de Oliveira Orientador Porto Alegre 2010 2 To my mother, the “dear name” who taught me to get through the shadows and labyrinths of my life 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am deeply thankful to: My advisor, Prof. Ubiratan Paiva de Oliveira, who first believed in this project, and whose competence and knowledge supported me until the end; My daughter, Isabela Montano Boessio, for her love and help as a graphic designer; To my teachers and friends who shared their knowledge, experience, and books with me. 4 “… to darkness, to nothingness, to earnestness, to home…” - Samuel Beckett (Malone Dies) 5 RESUMO O objeto de estudo desta tese é a composição pictórica de Ohio Impromptu, de Samuel Beckett. Sendo assim, apresenta uma poética visual como estratégia interdisciplinar de análise da obra, incluindo a sua versão em filme. A partir de sua contextualização histórico-social na pós-modernidade, tendo por base autores como Zygmunt Bauman e David Harvey, juntamente com a definição, delimitação e contextualização das referências artísticas presentes na peça e no filme, é analisado o modo como as escolhas pictóricas feitas pelo autor interferem no conceito de espaço e suas relações com o tempo, assim como o espaço do livro enquanto elemento de conexão entre espaço e tempo em relação ao espectador-leitor, Listener, Reader e autor. -

Playwright Brings Theatre to Inner City Kids

Playwright brings theatre to inner city kids http://www.cjnews.com/culture/arts/playwright-brings-theatre-i... November 10, 2016 - 9 Cheshvan 5777 PLAYWRIGHT BRINGS THEATRE TO INNER CITY KIDS By Amy Grief - November 9, 2016 Adam Seelig, founder of Little Goat Theatre Company. YURI DOJC PHOTO 1 of 4 16-11-09 11:53 PM Playwright brings theatre to inner city kids http://www.cjnews.com/culture/arts/playwright-brings-theatre-i... At the beginning of Adam Seelig’s newest show, PLAY: A (Mini) History of Theatre for Kids, the actors ask the audience, “Who made the first plays in the world?” And they answer: children. “Almost always, we have an audible response from the kids,” says Seelig, an award-winning poet, playwright and director who runs the, Haggadah-inspired (if only in name) One Little Goat Theatre Company. “And then we start to show children that making theatre, making plays, is rooted in the act of playing.” This is Seelig’s, and One Little Goat’s, first play for children. But Seelig has two kids and wanted to create something that would introduce a new generation to the world of theatre. While growing up in Vancouver, he remembers watching as theatre troupes performed in his elementary school. “I think that those performances were among the most influential I ever saw in my life,” he says. Seelig is quick to admit he didn’t write the whole play. He describes it as more of a collaboration or an adaptation since it’s littered with excerpts from well-known sources. -

Canadianliterature / Littérature Canadienne

Canadian Literature / Littérature canadienne A Quarterly of Criticism and Review Number 210/211, Autumn/Winter 2011, 21st-Century Poetics Published by The University of British Columbia, Vancouver Editor: Margery Fee Associate Editors: Judy Brown (Reviews), Joël Castonguay-Bélanger (Francophone Writing), Glenn Deer (Poetry), Laura Moss (Reviews), Deena Rymhs (Reviews) Past Editors: George Woodcock (1959–1977), W.H. New (1977–1995), Eva-Marie Kröller (1995–2003), Laurie Ricou (2003–2007) Editorial Board Heinz Antor University of Cologne Alison Calder University of Manitoba Cecily Devereux University of Alberta Kristina Fagan University of Saskatchewan Janice Fiamengo University of Ottawa Carole Gerson Simon Fraser University Helen Gilbert University of London Susan Gingell University of Saskatchewan Faye Hammill University of Strathclyde Paul Hjartarson University of Alberta Coral Ann Howells University of Reading Smaro Kamboureli University of Guelph Jon Kertzer University of Calgary Ric Knowles University of Guelph Louise Ladouceur University of Alberta Patricia Merivale University of British Columbia Judit Molnár University of Debrecen Lianne Moyes Université de Montréal Maureen Moynagh St. Francis Xavier University Reingard Nischik University of Constance Ian Rae King’s University College Julie Rak University of Alberta Roxanne Rimstead Université de Sherbrooke Sherry Simon Concordia University Patricia Smart Carleton University David Staines University of Ottawa Cynthia Sugars University of Ottawa Neil ten Kortenaar University of Toronto Marie Vautier University of Victoria Gillian Whitlock University of Queensland David Williams University of Manitoba Mark Williams Victoria University, New Zealand Editorial Margery Fee 21st-Century Poetics 6 Articles Scott Pound Language Writing and the Burden of Critique 9 Katie L. Price A ≠ A: The Potential for a ’Pataphysical Poetic in Dan Farrell’s The Inkblot Record 27 CanLit_210_211_6thProof.indd 1 12-02-22 8:52 PM Articles, continued Sarah Dowling Persons and Voices: Sounding Impossible Bodies in M. -

22.2 Sur-Teksts

Rampike 22/2 ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________ INDEX Andrew Topel p. 2 Editorial p. 3 George Bowering p. 4 Hal Jaffe & Joe Haske p. 6 Richard Kostelanetz p. 9 Phil Hall & Karl Jirgens p. 10 Aaron Daigle p. 15 Claude Gauvreau, Adam Seelig & Ray Ellenwood p. 16 Jill Darling p. 23 Gary Barwin p. 34 S.S. Prasad p. 36 Catherine Heard & Linda Steer p. 30 Jűrgen Olbrich p. 39 bpNichol Lane Workshop Cluster p. 40 Robert Anderson p. 40 Michael Boughn p. 42 Laine Bourassa p. 45 Zach Buck p. 46 David Peter Clark p. 48 Victor Coleman p. 50 Tyler Crick p. 51 Oliver Cusimano p. 54 Caleb R. Ellis p. 56 Kelly Semkiw p. 56 Jonathan Pappo p. 57 Andrew McEwan p. 58 Louise Bak p. 60 Stephen Brown p. 62 Jon Flieger p. 64 Marie-Hélène Tessier p. 66 W. Mark Sutherland p. 74 Nathan Dueck p. 75 Luciano Iacobelli & Beatriz Hausner p. 74 Nam June Paik p. 78 Gerry Shikatani p. 79 Jean-Claude Gagnon p. 80 Phil Hall: Cover Image 1 Rampike 22 /2 ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________ “Anatomy #2” by Andrew Topel (USA) “Illumination” by Andrew Topel (USA) 2 Rampike 22/2 ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Editorial: Dedicated to the memory of our fellow travellers. They have departed, but their voices live on. “Sorrows soar freely, with unbound feathered wings. When blue, I contemplate the world from above.” “Skumjas ir brīvas, un tām ir putnu brīvie spārni. Tapēc, kad man ir skumji, es skatos uz cilvēkiem no augšas.” – Imants Ziedonis [Trans. KJ]. Composer, Teacher, Poet, Fictioneer, Writer, Political Activist, Jazz Musician, Composer, Publisher, Latvian, Thinker, NIC GOTHAM RICHARD TRUHLAR IMANTS ZIEDONIS (1959-2013) (1950-2013) (1933-2013) Photo: Jānis Deinats Photo: Pearl Pirie Photo: LETA This issue of Rampike features flights of literary expression that contemplate the inter-active qualities of inspired text and impassioned imagination. -

Contributors

Contributors JONATHAN BALL is the author of Ex Machina (BookThug 2009) and the forthcoming Clockfire (Coach House 2010). He lives online at <www.jonathanball.com>. KATHLEEN BRowN's short fiction and poetry has been published in CV2 , dandelion, The Fiddlehead, QWERTY and the GULCH anthology (Tightrope Books). Her most recent play, "our mouths are filters," received a workshop production in the NB Acts Theatre Festival in Fredericton. "Road Story," a storytelling/performance collaboration, was presented in the 2009 Summerworks Performance Gallery. Kathleen is co-Artistic Director of the Toronto chapter of The Vagabond Trust. "On the mountain" is part of a multi-genre manuscript, "our mouths are filters: DOCUMENTING IN THE BRINK." ROGER FARR is the author SURPLUS; two new books, MEANS and IKMQ, are forthcoming. Recent creative and critical writing appears in Anarchist Studies, Canadian Literature, dandelion, Islands of Resistance: Pirate Radio in Canada, The Poetic Front, Politics is Not a Banana, The Postanarchism Reader, PRECIPICe, Rad Dad, and Social Anarchism. In February 2010 he co-hosted (with Stephen Collis) the anti-Olympics web-radio project, Short Range Poetic Device. He teaches in the Creative Writing and Culture and Technology Programs and edits CUE Books at Capilano University. PATRICK FRIESEN, former Winnipegger, lives near Victoria, where he is working on a manuscript of poetry and two monologues. He also teaches the occasional course for the Writing Department at the University of Victoria. His most recent books were Interim: Essays & Mediations and Earth's Crude Gravities. BROOK HouGLUM teaches at Capilano University and is currently researching North American poets theatre. -

Seeing Martin Niagara & Su Croll Government Phil Hall

PEDLAR PRESS Contact Us: 113 Bond Street St John’s, NL A1C 1T6 p: 709.738.6702 www.pedlarpress.com /pedlarpress @pedlarpress General & Publicity Inquiries: [email protected] Pedlar Press pursues its literary activities wherever humiliation and suffering and affronts to human dignity occur in Canada. That is, all across this country with its many broken systems. So much injustice cries out for literary attention. Pedlar authors and poets speak to injustices in their work, works of a challenging nature, works that do not accept the status quo, that make no compromise. The house vision is to acquire and promote works of exceptional literary beauty that meet very high standards for excellence in writing while also disturbing the silences regarding the widespread breakdown of social and political systems. We see our effort as a praxis—a social action toward political ends. One literary work of integrity can make a pronounced difference in the lives of many Canadians. Gutsy and gorgeous“ since 1996.” 49 FALL/WINTER FRONTLIST Seeing Martin Niagara & SU CROLL Government PHIL HALL Canadian Literary Fiction Canadian Poetry ISBN-13: 978-1-989424049 ISBN-13: 978-1-989424032 ISBN-10: 1-98942404X ISBN-10: 1-989424031 $22.00 CDN / $20.00 US $20.00 CDN / $18.00 US trade paperback trade paperback 5.5" x 8.5" | 288pp 6" x 8" | 128pp | 1 image Sept 2020 Sept 2020 Exploring the female gaze. Language is not a smart-aleck; it’s a sacred tinkerer. When art student Mira Samhain loses her father, she becomes preoc- “To tell what happened to you is not a poem,” writes Governor cupied with images of flesh and anguish. -

SEELIG-Charactor-Webpix-2-Mx8o

A D A M SE E L I G / EMERGENSEE: GET HEAD OUT OF ASS: !Charactor" and Poetic Theatre #$%&'$()*'$+',-*./'01.-.0$*-2'31.-.0$*-4'.&'5*'/6+5'($4'1.&',*0+)*'78&$'.6+$1*-').&/4'0+60*.9(6:' the person who performs. The play of our selves, by and through our selves (but not necessarily about;4'(&'$1*'<-.).'5*'6**<2'=1*.$-*').>',*'.':-*.$'.-$'?+-)4',8$'($'0+89<6%$',*')+-*'.,8&*<4' with acting reduced to an habitual bag of tricks yielding vacuous entertainment in lieu of serious @9*.&8-*4'9+A*B #$%&'$()*'$+',reak character so the actor can break through. Or if we bury character at least a little, the performer can surface, freeing her from the tacit obligation to imitate society and enabling her to radiate more of her actual self. Those who perform are never what they perform about. In fact, they are often more interesting and dynamic than the subjects they portray. Actors are highly sensitive, acute people, and, in being right before us, in the flesh, are always more present than what they represent. So why hide them? Their inalienable nature, as opposed to assigned character, should be the origin of their performance. As Noh &8::*&$&4'!C.01'@8@(9'1.&' 1(&'+56'A+(0*D'($'0.66+$',*').<*'$+'()($.$*"'EF*6+99+&.'.6<'G+86<'HI;2'J*$')+&$'+?'+8-'.0$+-&' (as directed by most of our directors, written by most of our writers, and created by most of our collectives) have been playing like Bottom with head all too much in ass K the mask that is their character consumes them entirely. -

Fall 2013 :: Photography

Contents Publication date Author Title Page October 17, 2013 Vladimir Keremidschieff Seize the Time: Vancouver Photographed 1967–1974 3 October 17, 2013 Graeme Truelove Svend Robinson: A Life in Politics 4 September 26, 2013 Peter Culley Parkway: Hammertown, Book 3 5 September 26, 2013 Ken Norris Rua Da Felicidade 6 August 15, 2013 Ronald Liversedge Mac-Pap: Memoir of a Canadian in the Spanish Civil War 7 August 15, 2013 Mark Leier Rebel Life, 2nd ed. 8 May 9, 2013 Rolf Knight Voyage Through the Past Century 9 October 3, 2011 Rolf Knight Along the No. 20 Line 10 November 15, 2010 Lawrence Aronsen City of Love and Revolution 11 May 14, 2010 Langlois, Sakolsky & van der Zon Islands of Resistance 12 November 15, 2012 Maleea Acker Gardens Aflame 13 November 15, 2012 Terry Glavin & Ben Parfitt Sturgeon Reach 14 May 16, 2011 Grant Buday Stranger on a Strange Island 15 May 9, 2013 George Stanley After Desire 16 November 29, 2012 Annharte [Marie Baker] Indigena Awry 17 August 15, 2013 Larissa Lai & Rita Wong sybil unrest 18 July 26, 2012 Roger Farr IKMQ 19 October 25, 2012 Roger Farr Means 20 April 5, 2011 Donato Mancini Buffet World 21 April 5, 2011 Roy Miki Mannequin Rising 22 October 15, 2011 Gary Barwin, Hugh Thomas, & Craig Conley Franzlations 23 June 15, 2010 Stan Persky & Brian Fawcett Robin Blaser 24 October 15, 2010 Adam Seelig Every Day In the Morning (slow) 25 October 25, 2012 George Bowering Words, Words, Words 26 November 15, 2010 George Bowering Caprice 27 July 26, 2012 Michael Tregebov The Shiva 28 November 15, 2010 Steve Weiner Sweet England 29 October 15, 2011 Ranj Dhaliwal Daaku: The Gangster’s Life 30 Complete backlist by title 31–33 Ordering information 33 Sales representatives 34 Manuscript submission guidelines | Contact information 34 2 New Release :: Fall 2013 :: Photography Vladimir Keremidschieff Seize the Time Vancouver Photographed 1967 – 1974 A photo portrait of Vancouver’s extended “summer of love,” BINDING Vladimir Keremidschieff’s Seize the Time captures an era Trade paperback of profound change in Lotusland. -

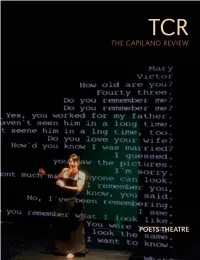

Cecily Nicholson for All We Know, Nothing Is Watching Summer Barrels Past

THE CAPILANO REVIEW The Capilano Review 3.27 Fall 2015 Fall ISSN 0315 3754 $16.00 O the rising and sinking and everything in between —Colin Smith Editor Andrea Actis Managing Editor Dylan Godwin Editorial Assistant Matea Kulić Editorial Board Colin Browne, Mark Cochrane, Pierre Coupey, Brook Houglum, Dorothy Jantzen, Aurelea Mahood, Jenny Penberthy, George Stanley Contributing Editors Clint Burnham, Roger Farr, Andrew Klobucar, Erín Moure, Lisa Robertson, Sharon Thesen Founding Editor Pierre Coupey Designer Andrea Actis Website Design Adam Jones The Capilano Review is published by the Capilano Review Contemporary Arts Society. Canadian subscription rates for one year are $35, $25 for students, $80 for institutions. Rates include S&H. Outside Canada, please add $5. Address correspondence to The Capilano Review, 281 Industrial Avenue, Vancouver, BC V6A 2P2. Subscribe online at www. thecapilanoreview.ca/order/. For submission guidelines, visit www.thecapilanoreview.ca/submissions. The Capilano Review does not accept hard-copy submissions, simultaneous submissions, previously published work, or submissions sent by email. Because copyright remains the property of the author or artist, no portion of this publication may be reproduced without the permission of the author or artist. The Capilano Review gratefully acknowledges the financial assistance of the Province of British Columbia, the British Columbia Arts Council, and the Canada Council for the Arts. We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Periodical Fund of the Department of Canadian Heritage. The Capilano Review is a member of Magazines Canada, the Magazine Association of BC, and the Alliance for Arts and Culture (Vancouver). Publications mail agreement number 40063611.