Introduction 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Good Evening, and Welcome on Behalf of Crossroads Cultural Center

Forward Together? A discussion on what the presidential campaign is revealing about the state of the American soul Speakers: Msgr. Lorenzo ALBACETE—Theologian, Author, Columnist Mr. Hendrik HERTZBERG—Executive Editor of The New Yorker Dr. Marvin OLASKY—Editor of World, Provost, The King‘s College Wednesday, March 12, 2008 at 7:00 PM, Columbia University, New York, NY Simmonds: Good evening, and welcome on behalf of Crossroads Cultural Center. Before we let Monsignor Albacete introduce our guests, we would like to explain very briefly what motivated us to organize tonight's discussion. Obviously, nowadays there is no lack of debate about the presidential elections. As should be expected, much of this debate focuses on the most current developments regarding the candidates, their policy proposals, shifts in the electorate, political alliances etc. All these are very interesting topics, of course, and are abundantly covered by the media. We felt, however, that it might be interesting to take a step back and try to ask some more general questions that are less frequently discussed, perhaps because they are harder to bring into focus and because they require more systematic reflection than is allowed by the regular news cycle. Given that politics is an important form of cultural expression, we would like to ask: What does the 2008 campaign say, if anything, about our culture? What do the candidates reveal, if anything, about our collective self-awareness and the way it is changing? Another way to ask essentially the same question is: What are the ideals that move people in America in 2008? Historically, great political movements have cultural and philosophical roots that go much deeper than politics in a strict sense. -

Collected Stories 1911-1937 Ebook, Epub

COLLECTED STORIES 1911-1937 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Edith Wharton | 848 pages | 16 Oct 2014 | The Library of America | 9781883011949 | English | New York, United States Collected Stories 1911-1937 PDF Book In "The Mission of Jane" about a remarkable adopted child and "The Pelican" about an itinerant lecturer , she discovers her gift for social and cultural satire. Sandra M. Marion Elizabeth Rodgers. Collected Stories, by Edith Wharton ,. Anson Warley is an ageing New York bachelor who once had high cultural aspirations, but he has left them behind to give himself up to the life of a socialite and dandy. Sort order. Michael Davitt Bell. A Historical Guide to Edith Wharton. With this two-volume set, The Library of America presents the finest of Wharton's achievement in short fiction: 67 stories drawn from the entire span of her writing life, including the novella-length works The Touchstone , Sanctuary , and Bunner Sisters , eight shorter pieces never collected by Wharton, and many stories long out-of-print. Anthony Trollope. The Edith Wharton Society Old but comprehensive collection of free eTexts of the major novels, stories, and travel writing, linking archives at University of Virginia and Washington State University. The Library of America series includes more than volumes to date, authoritative editions that average 1, pages in length, feature cloth covers, sewn bindings, and ribbon markers, and are printed on premium acid-free paper that will last for centuries. Elizabeth Spencer. Inspired by Your Browsing History. Books by Edith Wharton. Hill, Hamlin L. This work was followed several other novels set in New York. -

A New Model for Media Criticism: Lessons from the Schiavo Coverage

University of Miami Law Review Volume 61 Number 3 Volume 61 Number 3 (April 2007) SYMPOSIUM The Schiavo Case: Article 4 Interdisciplinary Perspectives 4-1-2007 A New Model for Media Criticism: Lessons from the Schiavo Coverage Lili Levi University of Miami School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umlr Part of the Family Law Commons, Health Law and Policy Commons, and the Medical Jurisprudence Commons Recommended Citation Lili Levi, A New Model for Media Criticism: Lessons from the Schiavo Coverage, 61 U. Miami L. Rev. 665 (2007) Available at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umlr/vol61/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Miami Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A New Model for Media Criticism: Lessons from the Schiavo Coverage LILI LEVI* I. INTRODUCTION ...................................................... 665 II. SHARPLY DIVIDED CRITICISM OF SCHIAVO MEDIA COVERAGE ................... 666 . III. How SHOULD WE ASSESS MEDIA COVERAGE? 674 A. JournalisticStandards ............................................ 674 B. Internal Limits of JournalisticStandards ............................. 677 C. Modern Pressures on Journalistic Standards and Editorial Judgment .... 680 1. CHANGES IN INDUSTRY STRUCTURE AND RESULTING ECONOMIC PRESSURES ................................................... 681 2. THE TWENTY-FOUR HOUR NEWS CYCLE ................................. 686 3. BLURRING THE DISTINCTION BETWEEN NEWS, OPINION, AND ENTERTAINMENT .............................................. 688 4. THE RISE OF BLOGS AND NEWS/COMMENTARY WEB SITES ................. 690 5. "NEWS AS CATFIGHT" - CHANGING DEFINITIONS OF BALANCE ........... -

Scanned Using Book Scancenter 5030

F ortieth Sacred H eart U niversity Fortieth U ndergraduate Commencement The Fourteenth of May Two Thousand and Six Eleven O'clock Fairfield, Connecticut Sacred Heart University Program Processional Nicole X. Cauvin, Ph.D. Professor of Sociology Mace Bearer and Marshal Words of Welcome Thomas V. Forget, Ph.D. Vice President for Academic Affairs National Anthem Michael Johnson Class o f2006 Invocation Jennifer Shackett Class of 2006 Presidential Welcome Anthony J. Cernera, Ph.D. President Conferral of Honorary Degrees Anthony J. Cernera, Ph.D. Maureen Howard Citation read by Michelle Loris, Ph.D. Professor of English Hood vested by Mr. James T. Morley, Trustee Rabbi Irving Greenberg, Ph.D. Citation read by Matthew D. Semel, J.D. Assistant Professor of Criminal Justice Hood vested by Mr. Howard J. Aibel, Trustee 2 Program Commencement Address Rabbi Irving Greenberg, Ph.D. President, Jewish Life Network/Steinhardt Foundation Presentation of Candidates fo r Undergraduate Degrees Reading of the candidates’names hy Department Chairs or their representatives Claire J. Paolini, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Stephen M. Brown, Ed.D. Dean of the John F. Welch College of Business Patricia W. Walker, Ed.D. Dean of the College of Education and Health Professions N ancy L. Sidoti, M.A.T. Dean of University College Conferral of Degrees and Presentation of Diplomas and Awards Anthony J. Cernera, Ph.D. class Presidents Greeting Amy E. N ardone Class of 2006 Alm a M ater Benediction Reverend Jean Ehret, Ph.D. University Chaplain Recessional 3 Alma Mater — It. V K K ____ n — • — p — '— o ------------------ 1. -

Democratization in Iraq by Kate Lotz and Tim Melvin

H UMAN R IGHTS & H UMAN W ELFARE Democratization in Iraq by Kate Lotz and Tim Melvin Prospects for political and economic success in Iraq are uncertain. The U.S.-led effort can fail in many ways, notably by a loss of political will in the face of terrorism and weak allies. On the other hand, success could change the shape of political institutions throughout the Middle East (Robert J. Barro in Business Week, April 5, 2004). In great numbers and under great risk, Iraqis have shown their commitment to democracy. By participating in free elections, the Iraqi people have firmly rejected the anti-democratic ideology of the terrorists. They have refused to be intimidated by thugs and assassins. And they have demonstrated the kind of courage that is always the foundation of self-government (George W. Bush, from Weekly Compilation of Presidential Documents, February 7, 2005). Restructuring Iraq's political system will be laden with difficulties, but it will certainly be feasible. At the same time, the blueprint for Iraq's democracy must reflect the unique features of Iraqi society. Once the system is in place, its benefits will quickly become evident to Iraq's various communities; if it brings economic prosperity (hardly unlikely given the country's wealth), the postwar structure will gradually, yet surely, acquire legitimacy (Adeed and Karen Dawisha in Foreign Affairs, May/June 2003). With the war in Iraq over, Coalition forces are still present as the cultivation of Iraqi democracy is underway. Coalition-led democratization in Iraq will prove to be a lengthy and complex objective, but one which will be pursued until successfully accomplished. -

{PDF EPUB} Grace Abounding by Maureen Howard Grace Abounding by Maureen Howard

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Grace Abounding by Maureen Howard Grace Abounding by Maureen Howard. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 65876259bb2684e0 • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. HOWARD, Maureen. Nationality: American. Born: Maureen Keans in Bridgeport, Connecticut, 28 June 1930. Education: Smith College, Northampton, Massachusetts, B.A. 1952. Family: Married 1) Daniel F. Howard in 1954 (divorced 1967), one daughter; 2) David J. Gordon in 1968; 3) Mark Probst, 1981. Career: Worked in publishing and advertising, 1952-54; lecturer in English, New School for Social Research, New York, 1967-68, 1970-71, and since 1974, and at University of California, Santa Barbara, 1968-69, Amherst College, Massachusetts, Brooklyn College, and Royale University. Currently, Member of the School of the Arts, Columbia University, New York. Awards: Guggenheim fellowship, 1967; Radcliffe Institute fellowship, 1967; National Book Critics Circle award, 1979; Merrill fellowship, 1982. Address: c/o Penguin, 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A. -

THE AMERICAN PRESIDENCY Undergraduate Lecture 01:512:205:01

THE HISTORY OF THE AMERICAN PRESIDENCY Undergraduate Lecture 01:512:205:01 Prof. David Greenberg Fall 2017 Class Time: MW 2:50pm - 4:10pm Room: VH 105 Email: [email protected] Phone: 646-504-5071 Office Hrs: TBA Office: 106 DeWitt Course No.: 01:512:205:01 Index No.: 17647 Syllabus updated 03/10/2017 Description. The course looks at the American Presidency in historical perspective. We examine the powers of the office, its place in the American imagination, and the achievements of the most significant presidents. Structured chronologically, the course emphasizes the growth and transformation of the office and how it has come to assume its dominant place in the political landscape. Individual presidents are studied to understand not only their own times but also salient issues with which they are associated (Jefferson and Adams with the rise of parties; Andrew Johnson with impeachment; etc.) A few thematic lectures break from the chronological thrust of the course to explore aspects of the presidency in greater depth across time. Course Requirements. Requirements means required—they are a must. Failure to fulfill requirements will mean failing the course. Regular attendance at lecture. In a class this large, I cannot take attendance. I recognize that some students will from time to time miss class. But it remains your responsibility to find out from other students in the class—not by emailing me— what you missed. Jobs, sports, or other extracurricular activities are never a legitimate excuse. Arriving on time and staying for the duration are also essential. If you have a standing commitment that will make you miss, come late to, or leave early from class with any frequency, you should not take this course. -

The Rhetoric of Jimmy Carter: Renewing America’S Confidence in Civic Leadership Through Speech and Political Education

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Winter 12-18-2020 The Rhetoric of Jimmy Carter: Renewing America’s Confidence in Civic Leadership through Speech and Political Education Christopher Bondi Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Part of the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Bondi, C. (2020). The Rhetoric of Jimmy Carter: Renewing America’s Confidence in Civic Leadership through Speech and Political Education (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/1927 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. THE RHETORIC OF JIMMY CARTER: RENEWING AMERICA’S CONFIDENCE IN CIVIC LEADERSHIP THROUGH SPEECH AND POLITICAL EDUCATION A Dissertation Submitted to the McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Christopher M. Bondi December 2020 Copyright by Christopher M. Bondi 2020 THE RHETORIC OF JIMMY CARTER: RENEWING AMERICA’S CONFIDENCE IN CIVIC LEADERSHIP THROUGH SPEECH AND POLITICAL EDUCATION By Christopher M. Bondi Approved May 1, 2020 ________________________________ ________________________________ Dr. Craig T. Maier, PhD Dr. Ronald C. Arnett, PhD Professor of Communication Professor of Communication (Committee Chair) (Committee Member) ________________________________ ________________________________ Dr. Janie Harden-Fritz, PhD Dr. Kristine L. Blair, PhD Professor of Communication Dean, McAnulty College and (Committee Member) Graduate School of Liberal Arts Professor of English iii ABSTRACT THE RHETORIC OF JIMMY CARTER: RENEWING AMERICA’S CONFIDENCE IN CIVIC LEADERSHIP THROUGH SPEECH AND POLITICAL EDUCATION By Christopher M. -

Shorenstein-Center-25Th-Anniversary

25 celebrating25years Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy John F. Kennedy School of Government Harvard University 79 John F. Kennedy Street Cambridge, MA 02138 617-495-8269 | www.shorensteincenter.org | @ShorensteinCtr 1986–2011 25th Anniversary | 1986–2011 1 From the Director The Shorenstein Center happily celebrates 25 years of teaching, research and engagement with the broad topic of media, politics and public policy. This publication describes the history of the Shorenstein Center and its programs. Our mission is to explore and illuminate the inter- section of media, politics and public policy both in theory and in practice. Through teaching and research at the Kennedy School; an active fellowship program; student workshops, scholarships and internships; speakers, prizes and endowed lectures; the Journalist’s Resource website, which is becoming an essential part of public policy reporting; and involvement in programs like the Carnegie-Knight Initiative on the Future of Journalism Education, the Shorenstein Center has been at the fore- front of new thinking about the media and politics. Over the past 25 years, our political climate has changed dramatically and the myriad tech- nological advances have changed the news business, and nearly every other business, entirely. Issues of free speech, civil liberty, national security, globalization and rising tensions between corporate and journalistic objectives confront us. The Shorenstein Center has embraced digital media and sought out new faculty, fellows, staff and speakers who are educating our students, conducting research and developing ideas about the role of digital technology in governance and other areas. It is an exciting time to be a part of Harvard (celebrating its 375th anniversary) and the Kennedy School (celebrating its 75th anniversary). -

The Time to Make Real the Promise of Democracy Fairvote 2006 Fairvote

the consent of the governed the time to make real the promise of democracy FairVote 2006 FairVote ... EQUAL WE THE PEOPLE the way democracy will be... FairVote FairVote pursues an innovative, solution-oriented pro-democracy FairVoteagenda. Our vision of an equally secure, meaningful and effective vote for all Americans is founded on the principles articulated in the Declaration of Independence, Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address and Martin Luther King’s I Have a Dream speech: we are created equal, government is of, by and for the people and it is time to make real the our vision promise of democracy. Founded in 1992 and operating for many years as the Center for Voting and Democracy, FairVote is the nation’s leading organization acting to transform our elections to achieve unfettered, fraud-free access to participation, a full spectrum of meaningful choices and majority rule with fair representation and a voice for all. Achieving our goals rests upon bold, but achievable reforms: a consti- tutionally protected right to vote, direct election of the president, instant runoff voting for executive elections and proportional voting for legislative elections. As a reform catalyst, we develop and promote practical strategies to improve elections for local, state and national leaders. 1 Letter From Our Chair 2-3 Effective Media & Advocacy 4-9 Programs 10 Indicators of Success 11 A Rising Base of Support 12-13 Our Leadership & Staff letter from our chair... FairVote ...the way democracy will be That’s our new slogan. It captures how our optimistic vision of democracy is at the cutting-edge of reform, but grounded in achievable strategies that have always defined our organization. -

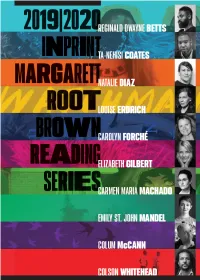

2019-2020-IBRS-Brochure.Pdf

DEAR FRIENDS Welcome to the 2019/2020 Inprint Margarett Root Brown Reading Series—our 39th season. At Inprint, we are proud of the role this series plays in the Houston community, each year presenting an inclusive roster of powerful, bold, award-winning authors whose work inspires and provokes conversation and reflection. Occupying that niche in the local landscape makes us happy—and ensuring that the series is accessible to all is a vital aspect of what we do. We are delighted to share the literary riches of this season—and the ensuing engagement with this work and these ideas—and are grateful to Houston for embracing it. Thank you, as always, for making all of this possible. See you at the readings. Cheers, RICH LEVY Executive Director Monday, September 16, 2019 COLSON WHITEHEAD CULLEN PERFORMANCE HALL, UNIVERSITY OF HOUSTON 2019|2020 Tuesday, October 29, 2019 TA-NEHISI COATES CULLEN PERFORMANCE HALL, UNIVERSITY OF HOUSTON Monday, November 11, 2019 INPRINT ELIZABETH GILBERT STUDE CONCERT HALL, RICE UNIVERSITY Monday, January 27, 2020 MARGARETT CAROLYN FORCHÉ & CARMEN MARIA MACHADO HUBBARD STAGE, ALLEY THEATRE ROOT Monday, March 9, 2020 LOUISE ERDRICH HUBBARD STAGE, ALLEY THEATRE Monday, March 23, 2020 BROWN REGINALD DWAYNE BETTS & NATALIE DIAZ HUBBARD STAGE, ALLEY THEATRE READING Monday, April 27, 2020 EMILY ST. JOHN MANDEL All readings take place at 7:30 pm & Doors open at 6:45 pm COLUM McCANN SERIES HUBBARD STAGE, ALLEY THEATRE TICKETS All readings begin at 7:30 pm, doors open at 6:45 pm. Each evening will include a reading by featured author(s) and an on-stage interview. -

How the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact Would Leave

Robbins.2017 (Do Not Delete) 4/20/2017 5:27 PM C A R D O Z O L A W R EVIEW de•novo CHANGING THE SYSTEM WITHOUT CHANGING THE SYSTEM: HOW THE NATIONAL POPULAR VOTE INTERSTATE COMPACT WOULD LEAVE NON- COMPACTING STATES WITHOUT A LEG TO STAND ON Jillian Robbins “[Y]ou win some, you lose some. And then there’s that little-known third category.”1 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 2 I. A FRAGMENTED, NEW NATION CREATED THE ELECTORAL COLLEGE: HOW THE SYSTEM IS NOT SUITABLE TODAY ................................................. 5 A. The Electoral College Has Failed Us: Historical Considerations........ 8 B. Common Criticisms of the Electoral College ........................................ 9 † Articles Editor, Cardozo Law Review Vol. 38. J.D. Candidate, Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law, 2017; B.A., University of Michigan, 2014. I would like to thank Professor Kate Shaw for her guidance and expertise in helping me write this Note. I also would like to thank all of my friends and family for their constant support during the entire Note-writing process. 1 Al Gore, Former Vice President, Address at the Democratic National Convention (July 26, 2004) (referring to when he won the national popular vote but lost the presidency in the infamous 2000 presidential election). 1 Robbins.2017 (Do Not Delete) 4/20/2017 5:27 PM 2 CARDOZO LAW REVIEW DE•NOVO [2017 C. Other Electoral College Reform Ideas That Fell Short....................... 11 D. The NPVIC: An Overview ................................................................... 12 II. A CONSTITUTIONAL DEBATE—THE ELECTORAL COLLEGE VERSUS THE COMPACT CLAUSE ....................................................................................... 15 A. The Electoral College: Article II, Section 1 .......................................