Magazine of History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Central Missouri, University of Vendor List

Central Missouri, University of Vendor List 4imprint Inc. Contact: Karla Kohlmann 866-624-3694 101 Commerce Street Oshkosh, WI 54901 [email protected] www.4imprint.com Number Type Status Contracts: 1052556 Standard Effective Products: Accessories - Convention Bag Accessories - Tote Accessories - Backpacks Accessories - purse, change Accessories - Luggage tags Accessories - Travel Bag Automobile Items - Ice Scraper Automobile Items - Key Tag/Chain Crew Sweatshirt - Fleece Crew Domestics - Table Cover Domestics - Cloth Domestics - Beach Towel Electronics - Flash Drive Electronics - Earbuds Furniture/Furnishings - Picture Frame Furniture/Furnishings - Screwdriver Furniture/Furnishings - Multi Tool Games - Bean Bag Toss Game Games - Playing Cards Garden Accessories - Seed Packet Gifts & Novelties - Button Gifts & Novelties - Key chains Gifts & Novelties - Koozie Gifts & Novelties - Lanyards Gifts & Novelties - tire gauge Gifts & Novelties - Rally Towel Golf/polo Shirts - Polo Shirt Headbands, Wristbands, Armband - Armband Headbands, Wristbands, Armband - Wristband Holiday - Ornament Home & Office - Fleece Blanket Home & Office - Dry Erase Sheets Home & Office - Night Light Home & Office - Mug Housewares - Jar Opener Housewares - Coasters Housewares - Tumbler Housewares - Drinkware - Glass Housewares - Cup Housewares - Tumbler Jackets / Coats - Jacket 04/02/2019 Page 1 of 91 Jackets / Coats - Coats - Winter Jewelry - Lapel Pin Jewelry - Spirit Bracelet Jewelry - Watches Miscellaneous - Umbrella Miscellaneous - Stress Ball Miscellaneous -

Patrick Henry

LIBERTY UNIVERSITY PATRICK HENRY: THE SIGNIFICANCE OF HARMONIZED RELIGIOUS TENSIONS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE HISTORY DEPARTMENT IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY BY KATIE MARGUERITE KITCHENS LYNCHBURG, VIRGINIA APRIL 1, 2010 Patrick Henry: The Significance of Harmonized Religious Tensions By Katie Marguerite Kitchens, MA Liberty University, 2010 SUPERVISOR: Samuel Smith This study explores the complex religious influences shaping Patrick Henry’s belief system. It is common knowledge that he was an Anglican, yet friendly and cooperative with Virginia Presbyterians. However, historians have yet to go beyond those general categories to the specific strains of Presbyterianism and Anglicanism which Henry uniquely harmonized into a unified belief system. Henry displayed a moderate, Latitudinarian, type of Anglicanism. Unlike many other Founders, his experiences with a specific strain of Presbyterianism confirmed and cooperated with these Anglican commitments. His Presbyterian influences could also be described as moderate, and latitudinarian in a more general sense. These religious strains worked to build a distinct religious outlook characterized by a respect for legitimate authority, whether civil, social, or religious. This study goes further to show the relevance of this distinct religious outlook for understanding Henry’s political stances. Henry’s sometimes seemingly erratic political principles cannot be understood in isolation from the wider context of his religious background. Uniquely harmonized -

Exhibition Catalog

The Missouri Historic Costume and Textile Collection presents FASHIONING A COLLECTION: 50 Years 50 Objects March 7 – May 20, 2017 State Historical Society of Missouri Gallery FASHIONING A COLLECTION: 50 YEARS, 50 OBJECTS Missouri Historic Costume and Textile Collection Department of Textile and Apparel Management College of Human Environmental Sciences University of Missouri State Historical Society of Missouri FASHIONING A COLLECTION: 50 YEARS, 50 OBJECTS Curated by Nicole Johnston and Jean Parsons The Missouri Historic Costume and Textile Collection was established in 1967 by Carolyn Wingo to support the teaching mission of the Department of Textile and Apparel Management within the College of Human Environmental Sciences at the University of Missouri. MHCTC received its first donation of artifacts from the Kansas City Museum in Kansas City, Missouri and has grown to include over 6,000 items of apparel, accessories and household textiles donated by alumni, faculty and friends. Curator Laurel Wilson guided and nurtured the collection for over half of the Collection’s fifty years, and today, the MHCTC collects and preserves clothing and textiles of historic and artistic value for purposes of teaching, research, exhibition and outreach. This exhibit celebrates the variety and mission of the collection, and is thus organized by the three branches of that mission: education, research and exhibition. It was a challenge to choose only 50 objects as representative. We have chosen those objects most frequently used in teaching and are student favorites, as well as objects used in research by undergraduate and graduate students, faculty, and visiting scholars. Finally, favorites from past exhibits are also included, as well as objects and new acquisitions that have never been previously exhibited. -

Joseph Smith Period Clothing 145

Carma de Jong Anderson: Joseph Smith Period Clothing 145 Joseph Smith Period Clothing: The 2005 Brigham Young University Exhibit Carma de Jong Anderson Early in 2005, administrators in Religious Education at Brigham Young University gave the green light to install an exhibit (hopefully my last) in the display case adjacent to the auditorium in the Joseph Smith Building. The display would showcase the clothing styles of the life span of the Prophet Joseph Smith and the people around him (1805–1844). There were eleven mannequins and clothing I had constructed carefully over many years, mingled with some of my former students’ items made as class projects. Those pieces came from my teaching the class, “Early Mormon Clothing 1800–1850,” at BYU several years ago. There were also a few original pieces from the Joseph Smith period. During the August 2005 BYU Education Week, thousands viewed these things, even though I rushed the ten grueling days of installation for something less than perfect.1 There was a constant flow of university students passing by and stopping to read extensive signage on all the contents shown. Mary Jane Woodger, associate professor of Church History and Doctrine, reported more young people and faculty paid attention to it than any other exhibit they have ever had. Sincere thanks were extend- ed from the members of Religious Education and the committee plan- ning the annual Sydney B. Sperry October symposium. My scheduled lectures to fifteen to fifty people, two or three times a week, day or night for six months (forty stints of two hours each), were listened to by many of the thirty thousand viewers who, in thank-you letters, were surprised at how much information could be gleaned from one exhibit. -

Portland Police Department Standard Operating Procedure

PORTLAND POLICE DEPARTMENT STANDARD OPERATING PROCEDURE Subject: Uniform and Civilian Attire Policy #: 102 Distribution: All Personnel Effective Date: 12/08/2013 Standards: COP Revision Date: 03/01/2020 By Order Of: Chief of Police Review: Biennially I. PURPOSE: The purpose of this policy is to regulate the appearance of officers and non‐sworn personnel by describing the police uniform and attendant police equipment, and acceptable attire for non‐ sworn employees. II. POLICY: It is the policy of the Portland Police Department to achieve and maintain the highest standards of professional integrity and public respect for individual police officers, Department personnel and the Department. Supervisory personnel will ensure that the articles of clothing and items specified in this directive are worn as required. All other items not specified herein are not permitted to be worn or carried. Exceptions to permissible or not permitted items to be worn or carried will only be allowed and authorized by specific permission from a member of the command staff. III. Definitions Body art: Art made on, with or consisting of the human body. Body art includes, but is not limited to, tattoos, piercings, shaping and body modification. Body art does not include procedures necessitated by deformity or injury or generally accepted cosmetic changes performed by or at the direction of a licensed medical professional. Body modification: a form of body art, body modification is the intentional alteration of the body, head, face, or skin to include inserting objects under the skin to create a design or pattern, gauging or stretching earlobes, intentional scarring or burning of skin to create a design or pattern. -

Bulletin of the State Normal School, Fredericksburg, Virginia, October

Vol. I OCTOBER, 1915 No. 3 BULLETIN OF THE State Normal Scnool Fredericksburg, Virginia The Rappahannock Rn)er Country By A. B. CHANDLER, Jr., M. A., Dean of Fredericksburg Normal School Published Annually in January, April, June and October Entered as second-class matter April 12, 1915, at the Post Office at Fredericksburg, Va., under the Act of August 24, 1912 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from LYRASIS Members and Sloan Foundation http://archive.org/details/bulletinofstaten13univ The Rappahannock River Country) By A. B. CHANDLER, Jr., M. A. Dean Fredericksburg Normal School No attempt is made to make a complete or logically arranged survey of the Rappahannock River country, because the limits of this paper and the writer's time do not permit it. Attention is called, however, to a few of the present day characteristics of this section of the State, its industries, and its people, and stress is laid upon certain features of its more ancient life which should prove of great interest to all Virginians. Considerable space is given also to the recital of strange experiences and customs that belong to an age long since past in Virginia, and in pointed contrast to the customs and ideals of to-day; and an insight is given into the life and services of certain great Virginians who lived within this area and whose life-work, it seems to me, has hitherto received an emphasis not at all commensurate with their services to the State and the Nation. The Rappahannock River country, embracing all of the counties from Fredericksburg to the mouth of this river, is beyond doubt one of the most beautiful, fertile and picturesque sections of Virginia. -

Chief Rodney Bryant Signature

Atlanta Police Department Standard Operating Policy Manual Procedure Effective Date APD.SOP.2130 December 30, 2020 Dress Code Applicable To: All Employees Review Due: 2024 Approval Authority: Chief Rodney Bryant Signature: Sign by RB Date Signed: 12/30/2020 Table of Content 4.3.20 Equipment and Leather Gear 23 1. PURPOSE 1 4.3.21 Traffic Vest 24 2. POLICY 2 4.3.22 Rain Gear 25 4.3.23 Gloves 25 3. RESPONSIBILITIES 2 4.3.24 SWAT 25 4.3.25 Explosive Ordinance Disposal (EOD) 25 4. ACTION 2 4.3.26 Mounted Patrol 26 4.1 General 2 4.3.27 APEX 26 4.2 General Appearance 3 4.3.28 Warrant Uniform 26 4.2.1 Tattoos and Brands 3 4.3.29 Bike Patrol / Bicycle Response Team (BRT) 26 4.2.2 Body Piercing 4 4.3.30 Aviation Unit 26 4.2.3 Hair 4 4.3.31 SOS Motors 27 4.2.4 Facial Hair 5 4.3.32 Auto Crimes Enforcement (ACE) 27 4.2.5 Make-up 5 4.3.33 Discretionary Units Assigned to the Zones 27 4.2.6 Fingernails 5 4.3.34 Training Section 27 4.2.7 Jewelry 5 4.3.35 Property Control Unit 28 4.2.8 Eyeglasses and Sunglasses 6 4.3.36 Police Athletic League (PAL) 28 4.2.9 General Uniform Guidelines 6 4.3.37 Honor Guard 28 4.3 Sworn Employees 6 4.3.38 Chaplains 28 4.3.1 Class A Uniform - Rank of Captain and Above 6 4.3.39 Temporary Assignments 28 4.3.2 Class A Uniform - Rank of Lieutenant and Below 7 4.3.40 Civil Disturbance Unit 28 4.3.3 Class B Uniform 8 4.3.41 Sworn Employees in Civilian Clothes 28 4.3.4 Class C Uniform - Rank of Lieutenant and Below 9 4.4 Non-sworn Employees 30 4.3.5 Badges 10 4.4.1 Recruits 30 4.3.6 Headgear 11 4.4.2 Traffic Control Inspectors 30 4.3.7 Metal Name Plate 12 4.4.3 Crime Prevention Inspectors 31 4.3.8 Rank Insignia 13 4.4.4 Property Management Technicians 31 4.3.9 Buttons 13 4.4.5 Vehicles for Hire Enforcement Officers 31 4.3.10 Collar Insignias 13 4.4.6 Inventory System Specialists 32 4.3.11 Shirt Accessories 14 4.4.7 Non-uniformed Civilian Employees 32 4.3.12 Specialized Assignment Patches 16 4.3.13 Shoes and Boots 17 5. -

1.1.C.5 Staff Dress and Grooming Standards

South Dakota Department Of Corrections Policy 1.1.C.5 Distribution: Public Staff Dress and Grooming Standards 1.1.C.5 Staff Dress and Grooming Standards I Policy Index: Date Signed: 05/24/2016 Distribution: Public Replaces Policy: 1C.12 Supersedes Policy Dated: 01/02/2016 Affected Units: All Units Effective Date: 05/25/2016 Scheduled Revision Date: November 2016 Revision Number: 12 Office of Primary Responsibility: DOC Administration II Policy: Staff representing the Department of Corrections (DOC) must have a professional appearance which promotes the professional image of the DOC. Staff will adhere to appropriate and professional dress and grooming standards while on duty. Staff working in a DOC facility must be cognizant of the potential dangers inherent in working in a correctional environment and dress accordingly. III Definitions: Staff Member: Any person employed by the DOC, full or part time, including an individual under contract assigned to the DOC, an employee of another state agency assigned to the DOC, authorized volunteers and student interns. Personal Body Alarm: A small battery powered emergency notification or alert device that when activated emits a loud sound (in excess of one hundred ten (110db) decibels). Activation occurs when the attached alarm pin is removed from the body of the alarm by pulling the lanyard. The alarm may be carried in a pocket or attached to a belt or waistline of the pants. Non-Uniform Staff: All DOC staff not required to wear an authorized DOC uniform. Business Casual Attire: Defined as less formal attire than worn on regular workdays (professional attire) but appropriate to the job functions being performed and the professional image of the DOC. -

Uniforms, Equipment, and Dress Code

GENERAL ORDER PORT WASHINGTON POLICE DEPARTMENT SUBJECT: UNIFORMS, EQUIPMENT, AND DRESS NUMBER: 2.4.2 CODE ISSUED: 5/5/09 SCOPE: All Police Personnel EFFECTIVE: 5/5/09 DISTRIBUTION: General Orders Manual RESCINDS B-1-80 9.1 AMENDS REFERENCE: WI State Statute 103(14) WILEAG 5th EDITION STANDARDS: 1.2.3, 2.4.4, 6.1.7 INDEX AS: Appearance Body Armor Dress Code Equipment Grooming Uniform PURPOSE: The purpose of this Order is to establish the uniform, appearance, and grooming standards for all Police Department employees as well as identify the equipment that is to be issued to each sworn officer. This Order contains one section which applies to the Sworn Officer Standards, and one section which applies to the Civilian Employee Standards. This Order consists of the following numbered sections: I. POLICY II. RESPONSIBILITY III. NON-CONFORMING UNIFORM OR CLOTHING SWORN OFFICER STANDARDS IV. UNIFORM & EQUIPMENT SPECIFICATIONS V. DEPARTMENT ISSUED UNIFORM & EQUIPMENT VI. BODY ARMOR VII. NON-ISSUE CLOTHING ITEMS VIII. LEATHER EQUIPMENT Revised 4/12/19 -1- General Order 2.4.2 IX. WEARING OF THE UNIFORM X. WEARING OF THE BIKE UNIFORM XI. WEARING THE UNIFORM OFF DUTY XII. COURT ROOM DRESS, PUBLIC APPEARANCES AND TRAINING XIII. JEWELRY, TATTOOS, PURSES, BUTTONS, AND ZIPPERS XIV. UNAUTHORIZED ITEMS NOT TO BE WORN ON UNIFORM XV. PERSONAL GROOMING XVI. INSPECTION OF EQUIPMENT & PERSONNEL CIVILIAN EMPLOYEE STANDARDS XVII. CLOTHING ATTIRE FOR CIVILIAN EMPLOYEES XVIII. AUTHORIZED UNIFORMS XIX. ITEMS TO BE PURCHASED AND PROVIDED BY EMPLOYER XX. ITEMS TO BE INITALLY PURCHASED BY EMPLOYEE I. POLICY A. The Port Washington Police Department functions in a business environment providing services to the community. -

Employee Guide

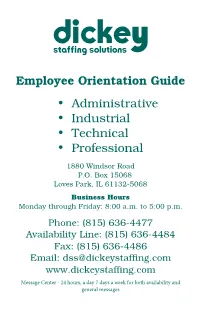

Employee Orientation Guide • Administrative • Industrial • Technical • Professional 1880 Windsor Road P.O. Box 15068 Loves Park, IL 61132-5068 Business Hours Monday through Friday: 8:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Phone: (815) 636-4477 Availability Line: (815) 636-4484 Fax: (815) 636-4486 Email: [email protected] www.dickeystaffing.com Message Center - 24 hours, a day 7 days a week for both availability and general messages Welcome to Dickey Staffing Solutions Thank you for selecting Dickey Staffing Solutions. We want you to be successful during your employment with us. Therefore, we have prepared this handbook to familiarize you with our company, its policies and procedures. These policies and procedures establish employment guidelines only. They do not establish an employment contract. Management reserves the right to unilaterally modify and change both policies and procedures. Dickey Staffing Solutions recognizes and supports that the terms, conditions and duration of employment are at will. Questions regarding this information are welcome and should be directed to your Dickey Staffing Solutions’ representative (DSS representative). Dickey Staffing Solutions was established in May of 1965. We are one of the oldest independently owned staffing firms in the Greater Rockford Area. Because of people like you, we are recognized and respected in the business community for our professionalism, commitment to superior customer service and quality personnel. We are recipients of the Rockford Area Chamber of Commerce Small Business Recognition Award. We serve a client base ranging from small emerging growth companies to Fortune 500 firms. It is our desire to develop a lasting relationship with you. -

Phillips Exeter Academy Parents' Handbook 2019-20

PARENTS’ HANDBOOK 2019–2020 WELCOME TO EXETER The Parents’ Handbook is a supplement to many of our other Academy publications. It was developed by the Dean of Students Office and is intended to help you as parents and guardians of our students to have a better understanding of how the school works. Based upon past conversations with parents and guardians, we have compiled a list of questions and aimed to provide a clear, concise answer for each. When appropriate, we refer you to other Academy publications for information, rather than repeating information here. We hope this answers many of your questions, but we encourage you to contact us if you ever have any questions about our policies, procedures, support services, etc. Throughout this book we have, for the sake of simplicity, referred to you as parents of our students. We do recognize that some students have guardians and we are always glad to work with those of you who serve in that capacity as well. Also on the subject of simpler word choices, a student is often referred to as “your child” — the phrase may sound a bit youthful when referring to a high school student, but after all, they are, and will always be, your children. In this book there are also several references to the Parent Portal, an additional online resource for Exeter parents. Personalized, and accessible only by users with authorized logins and passwords, the Parent Portal provides individual student grades and comments, dorm and adviser assignments, student schedules, and a host of useful information, such as handbooks, calendars, transportation information, and a parent directory. -

Steward Princeton Seminary.Indd 1 11/17/14 5:00 PM “I Warmly Recommend This Spiritually Edifying Book by Gary Steward

“An intelligent and edifying introduction to any of the key ideas of the modern era, and Christian responses to them, were formulated at the time of “Old the theology and leaders of Old Princeton. MPrinceton.” Gary Steward introduces us to the great men of A tremendous resource.” —Kevin DeYoung Princeton Theological Seminary from its founding to the early twen- tieth century, together with some of their most important writings. While commemorating the legacy of Old Princeton, this book also places the seminary in its historical and theological contexts. Princeton “Brilliantly resurrects the theologians of Old Princeton for today’s layman. Certainly, Steward’s engaging, accessible, and eloquent work is the new go-to book for the reader unacquainted with the Seminary giants of Old Princeton.” —Matthew Barrett, Associate Professor of Christian Studies, California Baptist University, Riverside, California 5 “The quality and achievement of Princeton Seminary’s leaders for (1812–1929) its first hundred years was outstanding, and Steward tells their story well. Reading this book does the heart good.” 55555555 555 555 —J. I. Packer, Board of Governors’ Professor of Theology, Regent 55 55 5 55 55 5 College, Vancouver, British Columbia 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 “Gary Steward is to be commended for providing an intelligent and 5 5 5 5 edifying introduction to the theology and leaders of Old Princeton. 5 5 5 5 The tone is warm and balanced, the content rich and accessible, the 5 5 5 5 5 historical work careful and illuminating. I hope pastors, students, 5 5 5 5 and anyone else interested in good theology and heartfelt piety will 5 5 5 5 5 ‘take a few classes’ at Old Princeton.” 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 —Kevin DeYoung, Senior Pastor, University Reformed Church 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 (PCA), East Lansing, Michigan 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 GARY STEWARD is an adjunct faculty member at California Baptist University in Riverside, California, and at Liberty University in Lynchburg, Virginia.