WAYS of NOT READING GERTRUDE STEIN by Natalia Cecire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nabokov and the Detective Novel

CATHARINE THEIMER NEPOMNYASHCHY NABOKOV AND THE DETECTIVE NOVEL atharine Theimer Nepomnyash- was left unfinished at her death. Cathy chy, Ann Whitney Olin Profes- proposed to investigate more thoroughly sor of Russian Literature and and inventively Nabokov’s enemies (Freud, C Culture, Barnard College, and Pasternak, the detective novel) to see former director of the Harriman Institute, whether his blistering invective obfuscated died on March 21 of this year. (An obitu- a deeper engagement with said enemies. ary is printed at the end of the magazine.) Although we can only guess at the work’s Cathy first taught the Nabokov survey at final shape, conference papers from 2010 Columbia in the fall of 2007 (I remember onwards offer glimpses of a potential table because I taught the second class), and the of contents: Nabokov and Pasternak; following year she published her first arti- Pale Fire and Doctor Zhivago: A Case of cle on Nabokov, “King, Queen, Sui-mate: Intertextual Envy; Ada and Bleak House ; Nabokov’s Defense Against Freud’s Un- Nabokov and Austen; Nabokov and the canny” (Intertexts, Spring 2008), the first Art of Attack. brick of what was planned to be “Nabokov The essay that follows is what we and His Enemies,” which unfortunately have of the second brick of Cathy’s 48 | HARRIMAN FEATURED INTRODUCTION BY RONALD MEYER work-in-progress, “Revising Nabokov needs to keep in mind that what follows is Revising the Detective Novel: Vladimir, a conference presentation and that Cathy Agatha, and the Terms of Engagement,” was writing within the constraints of time which Cathy presented at the 2010 Inter- and length, but one cannot but regret its national Nabokov Conference, sponsored preliminary state and wonder what was to by the Nabokov Society of Japan and the come in a fully expanded version. -

A Humble Protest a Literary Generation's Quest for The

A HUMBLE PROTEST A LITERARY GENERATION’S QUEST FOR THE HEROIC SELF, 1917 – 1930 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jason A. Powell, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Steven Conn, Adviser Professor Paula Baker Professor David Steigerwald _____________________ Adviser Professor George Cotkin History Graduate Program Copyright by Jason Powell 2008 ABSTRACT Through the life and works of novelist John Dos Passos this project reexamines the inter-war cultural phenomenon that we call the Lost Generation. The Great War had destroyed traditional models of heroism for twenties intellectuals such as Ernest Hemingway, Edmund Wilson, Malcolm Cowley, E. E. Cummings, Hart Crane, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and John Dos Passos, compelling them to create a new understanding of what I call the “heroic self.” Through a modernist, experience based, epistemology these writers deemed that the relationship between the heroic individual and the world consisted of a dialectical tension between irony and romance. The ironic interpretation, the view that the world is an antagonistic force out to suppress individual vitality, drove these intellectuals to adopt the Freudian conception of heroism as a revolt against social oppression. The Lost Generation rebelled against these pernicious forces which they believed existed in the forms of militarism, patriotism, progressivism, and absolutism. The -

Gertrude Stein and Her Audience: Small Presses, Little Magazines, and the Reconfiguration of Modern Authorship

GERTRUDE STEIN AND HER AUDIENCE: SMALL PRESSES, LITTLE MAGAZINES, AND THE RECONFIGURATION OF MODERN AUTHORSHIP KALI MCKAY BACHELOR OF ARTS, UNIVERSITY OF LETHBRIDGE, 2006 A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies of the University of Lethbridge in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS Department of English University of Lethbridge LETHBRIDGE, ALBERTA, CANADA © Kali McKay, 2010 Abstract: This thesis examines the publishing career of Gertrude Stein, an American expatriate writer whose experimental style left her largely unpublished throughout much of her career. Stein’s various attempts at dissemination illustrate the importance she placed on being paid for her work and highlight the paradoxical relationship between Stein and her audience. This study shows that there was an intimate relationship between literary modernism and mainstream culture as demonstrated by Stein’s need for the public recognition and financial gains by which success had long been measured. Stein’s attempt to embrace the definition of the author as a professional who earned a living through writing is indicative of the developments in art throughout the first decades of the twentieth century, and it problematizes modern authorship by re- emphasizing the importance of commercial success to artists previously believed to have been indifferent to the reaction of their audience. iii Table of Contents Title Page ………………………………………………………………………………. i Signature Page ………………………………………………………………………… ii Abstract ……………………………………………………………………………….. iii Table of Contents …………………………………………………………………….. iv Chapter One …………………………………………………………………………..... 1 Chapter Two ………………………………………………………………………….. 26 Chapter Three ………………………………………………………………………… 47 Chapter Four .………………………………………………………………………... 66 Works Cited .………………………………………………………………………….. 86 iv Chapter One Hostile readers of Gertrude Stein’s work have frequently accused her of egotism, claiming that she was a talentless narcissist who imposed her maunderings on the public with an undeserved sense of self-satisfaction. -

THE LITERARY CRITICISM of EDMUND WILSON by Mervin

TRADITION AND ISOLATION: THE LITERARY CRITICISM OF EDMUND WILSON by Mervin Butovsky A the sis submitted to the Faculty of G r aduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Mas ter of Arts. D e partment of English, M c Gill Univer s ity, M ontreal. A p r il 1961 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction 1 Chapter I Wilson's Cultural Tradition and Li.terary Career 13 Chapter II The Cost of Aestheticism: Llterature and Social Responsibility 47 Chapter III The Context of History: Marxism and Literary Values 67 Chapter IV The Context of Biography: Psychology and Literary Creation 86 Conclusion 111 Notes 121 List of Works Consulted 139 1 INTRODUCTION The position of Edmund Wilson is unique among critics on the American literary scene. For over three decades he has been considered one of America's leading critics of literature and i.s doubtless, as Stanley Edgar Hyman observes, "the most widely known 1 of our critics. " In an age when literary criticism has become greatly specialized and has tended to find its audience for the most part in academie circles, Edmund Wilson stands out as the only critic whose reputation is based upon critical acceptance by both the intellectuals and the broad literate reading public. Through the years his writings have been published in the avant-garde literary "little magazines" as well as the mass-circulated popular publications, 2 and unlike other prominent critics of literature, the majority of whom are teachers by profession, Wilson sees his writings as "the record of a journalist"3 and speaks of himself as belonging to the "serious profession of journalism. -

To the Finland Station Edmund Wilson

TO THE FINLAND STATION EDMUND WILSON INTRODUCTION BY LOUIS MENAND NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS CLASSICS TO THE FINLAND STATION EDMUND WILSON (1895–1972) is widely regarded as the preeminent American man of letters of the twentieth century. Over his long career, he wrote for Vanity Fair, helped edit The New Republic, served as chief book critic for The New Yorker, and was a frequent contributor to The New York Review of Books. Wilson was the author of more than twenty books, including Axel’s Castle, Patriotic Gore, and a work of fiction, Memoirs of Hecate County. LOUIS MENAND is Distinguished Professor of English at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York and a staff writer at The New Yorker. He is the author of The Meta- physical Club, which won the Pulitzer Prize for History and the Francis Parkman Prize in 2002, and American Studies, a collection of essays. TO THE FINLAND STATION A STUDY IN THE WRITING AND ACTING OF HISTORY EDMUND WILSON Foreword by LOUIS MENAND new york review books nyrb New York This is a New York Review Book Published by The New York Review of Books 1755 Broadway, New York, NY 10019 Copyright 1940 by Harcourt Brace & Co., Inc., renewed 1967 by Edmund Wilson. New introduction and revisions copyright © 1972 by the Estate of Edmund Wilson. Published by arrangement with Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC. Introduction copyright © 2003 by Louis Menand All rights reserved Marxism at the End of the Thirties, from The Shores of Light, copyright 1952 by Edmund Wilson Farrar, Straus & Young, Inc., Publishers. -

![Ida, a [Performative] Novel and the Construction of Id/Entity](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4638/ida-a-performative-novel-and-the-construction-of-id-entity-1024638.webp)

Ida, a [Performative] Novel and the Construction of Id/Entity

Wesleyan University The Honors College Ida, A [Performative] Novel and the Construction of Id/Entity by Katherine Malczewski Class of 2015 A thesis submitted to the faculty of Wesleyan University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Departmental Honors in Theater Middletown, Connecticut April, 2015 Malczewski 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgments……………………………………………………………………..2 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………3 Stein’s Theoretical Framework………………………………………………………..4 Stein’s Writing Process and Techniques……………………………………………..12 Ida, A Novel: Context and Textual Analysis………………………………...……….17 Stein’s Theater, the Aesthetics of the Performative, and the Actor’s Work in Ida…………………………………………………25 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………...40 Notes…………………………………………………………………………………41 Appendix: Adaptation of Ida, A Novel……………………………....………………44 Works Cited………………………………………………………………………….56 Malczewski 2 Acknowledgments Many thanks to all the people who have supported me throughout this process: To my director, advisor, and mentor, Cláudia Tatinge Nascimento. You ignited my passion for both the works of Gertrude Stein and “weird” theater during my freshman year by casting me in Doctor Faustus Lights the Lights. Since then, you have offered me with invaluable guidance and insight, teaching me that the process is just as important as the performance. I am eternally grateful for all the time and energy you have dedicated to this project. To the Wesleyan Theater Department, for guiding me throughout my four years at Wesleyan, encouraging me to embrace collaboration, and making the performance of Ida, A Novel possible. Special thanks to Marcela Oteíza and Leslie Weinberg, for your help and advice during the process of Ida. To my English advisors, Courtney Weiss Smith and Rachel Ellis Neyra, for challenging me to think critically and making me a better writer in the process. -

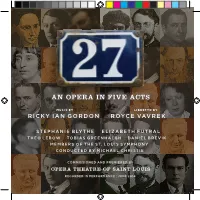

An Opera in Five Acts

AN OPERA IN FIVE ACTS MUSIC BY LIBRETTO BY RICKY IAN GORDON ROYCE VAVREK STEPHANIE BLYTHE ELIZABETH FUTRAL THEO LEBOW TOBIAS GREENHALGH DANIEL BREVIK MEMBERS OF THE ST. LOUIS SYMPHONY CONDUCTED BY MICHAEL CHRISTIE COMMISSIONED AND PREMIERED BY OPERA THEATRE OF SAINT LOUIS RECORDED IN PERFORMANCE : JUNE 2014 1 CD 1 1) PROLOGUE | ALICE KNITS THE WORLD [5:35] ACT ONE 2) SCENE 1 — 27 RUE DE FLEURUS [10:12] ALICE B. TOKLAS 3) SCENE 2 — GERTRUDE SITS FOR PABLO [5:25] AND GERTRUDE 4) SCENE 3 — BACK AT THE SALON [15:58] STEIN, 1922. ACT TWO | ZEPPELINS PHOTO BY MAN RAY. 5) SCENE 1 — CHATTER [5:21] 6) SCENE 2 — DOUGHBOY [4:13] SAN FRANCISCO ACT THREE | GÉNÉRATION PERDUE MUSEUM OF 7) INTRODUCTION; “LOST BOYS” [5:26] MODERN ART. 8) “COME MEET MAN RAY” [5:48] 9) “HOW WOULD YOU CHOOSE?” [4:59] 10) “HE’S GONE, LOVEY” [2:30] CD 2 ACT FOUR | GERTRUDE STEIN IS SAFE, SAFE 1) INTRODUCTION; “TWICE DENYING A WAR” [7:36] 2) “JURY OF MY CANVAS” [6:07] ACT FIVE | ALICE ALONE 3) INTRODUCTION; “THERE ONCE LIVED TWO WOMEN” [8:40] 4) “I’VE BEEN CALLED MANY THINGS" [8:21] 2 If a magpie in the sky on the sky can not cry if the pigeon on the grass alas can alas and to pass the pigeon on the grass alas and the magpie in the sky on the sky and to try and to try alas on the grass the pigeon on the grass and alas. They might be very well very well very ALICE B. -

A Critical Study of the Loss and Gain of the Lost Generation

Opción, Año 34, Especial No.15 (2018): 1436-1463 ISSN 1012-1587/ISSNe: 2477-9385 A Critical Study of the Loss and Gain of the Lost Generation Seyedeh Zahra Nozen1 1Department of English, Amin Police Science University [email protected] Shahriar Choubdar (MA) Malayer University, Malayer, Iran [email protected] Abstract This study aims to the evaluation of the features of the group of writers who chose Paris as their new home to produce their works and the overall dominant atmosphere in that specific time in the generation that has already experienced war through comparative research methods. As a result, writers of this group tried to find new approaches to report different contexts of modern life. As a conclusion, regardless of every member of the lost generation bohemian and wild lifestyles, the range, creativity, and influence of works produced by this community of American expatriates in Paris are remarkable. Key words: Lost Generation, World War, Disillusionment. Recibido: 04-12--2017 Aceptado: 10-03-2018 1437 Zahra Nozen and Shahriar Choubdar Opción, Año 34, Especial No.15(2018):1436-1463 Un estudio crítico de la pérdida y ganancia de la generación perdida Resumen Este estudio tiene como objetivo la evaluación de las características del grupo de escritores que eligieron París como su nuevo hogar para producir sus obras y la atmósfera dominante en ese momento específico en la generación que ya ha experimentado la guerra a través de métodos de investigación comparativos. Como resultado, los escritores de este grupo trataron de encontrar nuevos enfoques para informar diferentes contextos de la vida moderna. -

Edmund Wilson's Chronicles Edwin Honig

New Mexico Quarterly Volume 24 | Issue 1 Article 15 1954 Edmund Wilson's Chronicles Edwin Honig Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmq Recommended Citation Honig, Edwin. "Edmund Wilson's Chronicles." New Mexico Quarterly 24, 1 (1954). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmq/vol24/ iss1/15 This Contents is brought to you for free and open access by the University of New Mexico Press at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Quarterly by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Honig: Edmund Wilson's Chronicles BOOKS and COMMENT Edwin Honig EDMUND WILSON'S CHRONICLES1 DMUNDWIL SON is that rare sort of American writer, a master of prose style. This can probably be proved at E length from any of his ten books of critical and discursive pros~. His writing has no crotchets. It reads easily; it is often bril liant without being simply slick. He seems unwilling to let a dead or merely dull sentence slip by. Though occasionally his periods seem protracted. they easily pass scrutiny because they are not densely freighted or rhetorical and carry their weight of modifi ers and parentheses squarely. The right sense of conviction and discriminative zeal keeps them afloat. Such qua~ities are remark able enough even in a critic ofdeliberate intent who publishes only infrequently. But the example of Edmund Wilson, a literary journalist of thirty years standing whose work 'was composed for \ weeklies like The New Republicand The New Yorketr, has quali- tatively almost no precedent in our literature. -

Representation, Re-Presentation, and Repetition of the Past in Gertrude

Representation, Re-presentation, and Repetition of the Past in Gertrude Stein’s The Making of Americans by Alexandria Sanborn Representation, Re-presentation, and Repetition of the Past in Gertrude Stein’s The Making of Americans by Alexandria Sanborn A thesis presented for the B. A. degree with Honors in The Department of English University of Michigan Spring 2011 © March 2011, Alexandria Mary Sanborn This thesis is dedicated my father. Even as he remains my most exasperating critic, his opinion has always mattered most to me. Acknowledgements I would like to thank my adviser, Andrea Zemgulys for her help and guidance throughout this project. At the start of this year, I was unsure about what I wanted to say about Stein, and our initial conversation guided me back to ideas I needed to continue pursuing. As I near the finish line, I look back at my initial drafts and am flooded with gratitude for her ability to tactfully identify the strengths and weaknesses of my argument while parsing through my incoherent prose. She was always open and responsive to my ideas and encouraged me to embrace them as my own, which gave me the confidence to enter a critical conversation that seemed to resist my reading of Stein. Next, I thank Cathy Sanok and Honors English cohort who have provided valuable feedback about my writing throughout the drafting process and were able to truly understand and commiserate with me during the more stressful periods of writing. Through the financial support of the Wagner Bursary, I had the opportunity to visit the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University to read Stein’s notebooks and early drafts of The Making of Americans. -

Reading Cruft: a Cognitive Approach to the Mega-Novel

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2014 Reading Cruft: A Cognitive Approach to the Mega-Novel David J. Letzler Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/247 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] READING CRUFT A COGNITIVE APPROACH TO THE MEGA-NOVEL by DAVID LETZLER A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2014 © 2014 DAVID JOSEPH LETZLER All rights reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in English in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Gerhard Joseph _______________________ ___________________________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Mario DiGangi _______________________ ___________________________________________ Date Executive Officer Gerhard Joseph Nico Israel Mario DiGangi Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract READING CRUFT: A COGNITIVE APPROACH TO THE MEGA-NOVEL by David Letzler Adviser: Gerhard Joseph Reading Cruft offers a new critical model for examining a genre vital to modern literature, the mega-novel. Building on theoretical work in both cognitive narratology and cognitive poetics, it argues that the mega-novel is primarily characterized by its inclusion of a substantial amount of pointless text (“cruft”), which it uses to challenge its readers’ abilities to modulate their attention and rapidly shift their modes of text processing. -

The Literary Heroes of Fitzgerald and Hemingway ; Updike and Bellow Martha Ristine Skyrms Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1979 The literary heroes of Fitzgerald and Hemingway ; Updike and Bellow Martha Ristine Skyrms Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Skyrms, Martha Ristine, "The literary heroes of Fitzgerald and Hemingway ; Updike and Bellow " (1979). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 6966. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/6966 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The literary heroes of Fitzgerald and Hemingway; Updike and Bellow by Martha Ristine Skyrms A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: English Approved: Signatures have been redacted for privacy Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1979 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION 1 The Decades 1 FITZGERALD g The Fitzgerald Hero 9 g The Fitzgerald Hero: Summary 27 ^ HEMINGWAY 29 . The Hemingway Hero 31 ^ The Hemingway Hero; Summary 43 THE HERO OF THE TWENTIES 45 UPDIKE 47 The Updike Hero 43 The Updike Hero: Summary 67 BELLOW 70 The Bellow Hero 71 The Bellow Hero: Summary 9I THE HERO OF THE SIXTIES 93 ir CONCLUSION 95 notes , 99 Introduction 99 Fitzgerald 99 Hemingway j_Oi The Hero of the Twenties loi Updike 1Q2 Bellow BIBLIOGRAPHY 104 INTRODUCTION 9 This thesis will undertake an examination of the literary heroes of the nineteen-twenties and the nineteen-sixties, emphasizing the qualities which those heroes share and those qualities which distinguish them.