Music in Theory and Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4. Non-Heptatonic Modes

Tagg: Everyday Tonality II — 4. Non‐heptatonic modes 151 4. Non‐heptatonic modes If modes containing seven different scale degrees are heptatonic, eight‐note modes are octatonic, six‐note modes hexatonic, those with five pentatonic, while four‐ and three‐note modes are tetratonic and tritonic. Now, even though the most popular pentatonic modes are sometimes called ‘gapped’ because they contain two scale steps larger than those of the ‘church’ modes of Chapter 3 —doh ré mi sol la and la doh ré mi sol, for example— they are no more incomplete FFBk04Modes2.fm. 2014-09-14,13:57 or empty than the octatonic start to example 70 can be considered cluttered or crowded.1 Ex. 70. Vigneault/Rochon (1973): Je chante pour (octatonic opening phrase) The point is that the most widespread convention for numbering scale degrees (in Europe, the Arab world, India, Java, China, etc.) is, as we’ve seen, heptatonic. So, when expressions like ‘thirdless hexatonic’ occur in this chapter it does not imply that the mode is in any sense deficient: it’s just a matter of using a quasi‐global con‐ vention to designate a particular trait of the mode. Tritonic and tetratonic Tritonic and tetratonic tunes are common in many parts of the world, not least in traditional music from Micronesia and Poly‐ nesia, as well as among the Māori, the Inuit, the Saami and Native Americans of the great plains.2 Tetratonic modes are also found in Christian psalm and response chanting (ex. 71), while the sound of children chanting tritonic taunts can still be heard in playgrounds in many parts of the world (ex. -

Tonality in My Molto Adagio

Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre Jorge Gómez Rodríguez Constructing Tonality in Molto Adagio A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music) Supervisor: Prof. Mart Humal Tallinn 2015 Abstract The focus of this paper is the analysis of the work for string ensemble entitled And Silence Eternal - Molto Adagio (Molto Adagio for short), written by the author of this thesis. Its originality lies in the use of a harmonic approach which is referred to as System of Harmonic Classes in this thesis. Owing to the relatively unconventional employment of otherwise traditional harmonic resources in this system, a preliminary theoretical framework needs to be put in place in order to construct an alternative tonal approach that may describe the pitch structure of the Molto Adagio. This will be the aim of Part 1. For this purpose, analytical notions such as symmetric pair, primary dominant factor, harmonic domain, and harmonic area will be introduced before the tonal character of the piece (or the extent to which Molto Adagio may be said to be tonal) can be assessed. A detailed description of how the composer envisions and constructs the system will follow, with special consideration to the place the major diatonic scale occupies in relation to it. Part 2 will engage in an analysis of the piece following the analytical directives gathered in Part 1. The concept of modular tonality, which incorporates the notions of harmonic area and harmonic classes, will be put forward as a heuristic term to account for the use of a linear analytical approach. -

Second Bassoon: Specialist, Support, Teamwork Dick Hanemaayer Amsterdam, Holland (!E Following Article first Appeared in the Dutch Magazine “De Fagot”

THE DOUBLE REED 103 Second Bassoon: Specialist, Support, Teamwork Dick Hanemaayer Amsterdam, Holland (!e following article first appeared in the Dutch magazine “De Fagot”. It is reprinted here with permission in an English translation by James Aylward. Ed.) t used to be that orchestras, when they appointed a new second bassoon, would not take the best player, but a lesser one on instruction from the !rst bassoonist: the prima donna. "e !rst bassoonist would then blame the second for everything that went wrong. It was also not uncommon that the !rst bassoonist, when Ihe made a mistake, to shake an accusatory !nger at his colleague in clear view of the conductor. Nowadays it is clear that the second bassoon is not someone who is not good enough to play !rst, but a specialist in his own right. Jos de Lange and Ronald Karten, respectively second and !rst bassoonist from the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra explain.) BASS VOICE Jos de Lange: What makes the second bassoon more interesting over the other woodwinds is that the bassoon is the bass. In the orchestra there are usually four voices: soprano, alto, tenor and bass. All the high winds are either soprano or alto, almost never tenor. !e "rst bassoon is o#en the tenor or the alto, and the second is the bass. !e bassoons are the tenor and bass of the woodwinds. !e second bassoon is the only bass and performs an important and rewarding function. One of the tasks of the second bassoon is to control the pitch, in other words to decide how high a chord is to be played. -

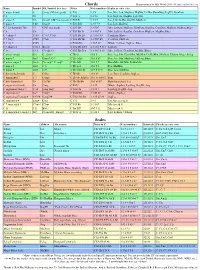

Chords and Scales 30/09/18 3:21 PM

Chords and Scales 30/09/18 3:21 PM Chords Charts written by Mal Webb 2014-18 http://malwebb.com Name Symbol Alt. Symbol (best first) Notes Note numbers Scales (in order of fit). C major (triad) C Cmaj, CM (not good) C E G 1 3 5 Ion, Mix, Lyd, MajPent, MajBlu, DoHar, HarmMaj, RagPD, DomPent C 6 C6 C E G A 1 3 5 6 Ion, MajPent, MajBlu, Lyd, Mix C major 7 C∆ Cmaj7, CM7 (not good) C E G B 1 3 5 7 Ion, Lyd, DoHar, RagPD, MajPent C major 9 C∆9 Cmaj9 C E G B D 1 3 5 7 9 Ion, Lyd, MajPent C 7 (or dominant 7th) C7 CM7 (not good) C E G Bb 1 3 5 b7 Mix, LyDom, PhrDom, DomPent, RagCha, ComDim, MajPent, MajBlu, Blues C 9 C9 C E G Bb D 1 3 5 b7 9 Mix, LyDom, RagCha, DomPent, MajPent, MajBlu, Blues C 7 sharp 9 C7#9 C7+9, C7alt. C E G Bb D# 1 3 5 b7 #9 ComDim, Blues C 7 flat 9 C7b9 C7alt. C E G Bb Db 1 3 5 b7 b9 ComDim, PhrDom C 7 flat 5 C7b5 C E Gb Bb 1 3 b5 b7 Whole, LyDom, SupLoc, Blues C 7 sharp 11 C7#11 Bb+/C C E G Bb D F# 1 3 5 b7 9 #11 LyDom C 13 C 13 C9 add 13 C E G Bb D A 1 3 5 b7 9 13 Mix, LyDom, DomPent, MajBlu, Blues C minor (triad) Cm C-, Cmin C Eb G 1 b3 5 Dor, Aeo, Phr, HarmMin, MelMin, DoHarMin, MinPent, Ukdom, Blues, Pelog C minor 7 Cm7 Cmin7, C-7 C Eb G Bb 1 b3 5 b7 Dor, Aeo, Phr, MinPent, UkDom, Blues C minor major 7 Cm∆ Cm maj7, C- maj7 C Eb G B 1 b3 5 7 HarmMin, MelMin, DoHarMin C minor 6 Cm6 C-6 C Eb G A 1 b3 5 6 Dor, MelMin C minor 9 Cm9 C-9 C Eb G Bb D 1 b3 5 b7 9 Dor, Aeo, MinPent C diminished (triad) Cº Cdim C Eb Gb 1 b3 b5 Loc, Dim, ComDim, SupLoc C diminished 7 Cº7 Cdim7 C Eb Gb A(Bbb) 1 b3 b5 6(bb7) Dim C half diminished Cø -

An Adaptive Tuning System for MIDI Pianos

David Løberg Code Groven.Max: School of Music Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, MI 49008 USA An Adaptive Tuning [email protected] System for MIDI Pianos Groven.Max is a real-time program for mapping a renstemningsautomat, an electronic interface be- performance on a standard keyboard instrument to tween the manual and the pipes with a kind of arti- a nonstandard dynamic tuning system. It was origi- ficial intelligence that automatically adjusts the nally conceived for use with acoustic MIDI pianos, tuning dynamically during performance. This fea- but it is applicable to any tunable instrument that ture overcomes the historic limitation of the stan- accepts MIDI input. Written as a patch in the MIDI dard piano keyboard by allowing free modulation programming environment Max (available from while still preserving just-tuned intervals in www.cycling74.com), the adaptive tuning logic is all keys. modeled after a system developed by Norwegian Keyboard tunings are compromises arising from composer Eivind Groven as part of a series of just the intersection of multiple—sometimes oppos- intonation keyboard instruments begun in the ing—influences: acoustic ideals, harmonic flexibil- 1930s (Groven 1968). The patch was first used as ity, and physical constraints (to name but three). part of the Groven Piano, a digital network of Ya- Using a standard twelve-key piano keyboard, the maha Disklavier pianos, which premiered in Oslo, historical problem has been that any fixed tuning Norway, as part of the Groven Centennial in 2001 in just intonation (i.e., with acoustically pure tri- (see Figure 1). The present version of Groven.Max ads) will be limited to essentially one key. -

Computational Methods for Tonality-Based Style Analysis of Classical Music Audio Recordings

Fakult¨at fur¨ Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik Computational Methods for Tonality-Based Style Analysis of Classical Music Audio Recordings Christof Weiß geboren am 16.07.1986 in Regensburg Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktoringenieur (Dr.-Ing.) Angefertigt im: Fachgebiet Elektronische Medientechnik Institut fur¨ Medientechnik Fakult¨at fur¨ Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik Gutachter: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Dr. rer. nat. h. c. mult. Karlheinz Brandenburg Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Meinard Muller¨ Prof. Dr. phil. Wolfgang Auhagen Tag der Einreichung: 25.11.2016 Tag der wissenschaftlichen Aussprache: 03.04.2017 urn:nbn:de:gbv:ilm1-2017000293 iii Acknowledgements This thesis could not exist without the help of many people. I am very grateful to everybody who supported me during the work on my PhD. First of all, I want to thank Prof. Karlheinz Brandenburg for supervising my thesis but also, for the opportunity to work within a great team and a nice working enviroment at Fraunhofer IDMT in Ilmenau. I also want to mention my colleagues of the Metadata department for having such a friendly atmosphere including motivating scientific discussions, musical activity, and more. In particular, I want to thank all members of the Semantic Music Technologies group for the nice group climate and for helping with many things in research and beyond. Especially|thank you Alex, Ronny, Christian, Uwe, Estefan´ıa, Patrick, Daniel, Ania, Christian, Anna, Sascha, and Jakob for not only having a prolific working time in Ilmenau but also making friends there. Furthermore, I want to thank several students at TU Ilmenau who worked with me on my topic. Special thanks go to Prof. -

Out of Death and Despair: Elements of Chromaticism in the Songs of Edvard Grieg

Ryan Weber: Out of Death and Despair: Elements of Chromaticism in the Songs of Edvard Grieg Grieg‘s intriguing statement, ―the realm of harmonies has always been my dream world,‖1 suggests the rather imaginative disposition that he held toward the roles of harmonic function within a diatonic pitch space. A great degree of his chromatic language is manifested in subtle interactions between different pitch spaces along the dualistic lines to which he referred in his personal commentary. Indeed, Grieg‘s distinctive style reaches beyond common-practice tonality in ways other than modality. Although his music uses a variety of common nineteenth- century harmonic devices, his synthesis of modal elements within a diatonic or chromatic framework often leans toward an aesthetic of Impressionism. This multifarious language is most clearly evident in the composer‘s abundant songs that span his entire career. Setting texts by a host of different poets, Grieg develops an approach to chromaticism that reflects the Romantic themes of death and despair. There are two techniques that serve to characterize aspects of his multi-faceted harmonic language. The first, what I designate ―chromatic juxtapositioning,‖ entails the insertion of highly chromatic material within ^ a principally diatonic passage. The second technique involves the use of b7 (bVII) as a particular type of harmonic juxtapositioning, for the flatted-seventh scale-degree serves as a congruent agent among the realms of diatonicism, chromaticism, and modality while also serving as a marker of death and despair. Through these techniques, Grieg creates a style that elevates the works of geographically linked poets by capitalizing on the Romantic/nationalistic themes. -

On Modulation —

— On Modulation — Dean W. Billmeyer University of Minnesota American Guild of Organists National Convention June 25, 2008 Some Definitions • “…modulating [is] going smoothly from one key to another….”1 • “Modulation is the process by which a change of tonality is made in a smooth and convincing way.”2 • “In tonal music, a firmly established change of key, as opposed to a passing reference to another key, known as a ‘tonicization’. The scale or pitch collection and characteristic harmonic progressions of the new key must be present, and there will usually be at least one cadence to the new tonic.”3 Some Considerations • “Smoothness” is not necessarily a requirement for a successful modulation, as much tonal literature will illustrate. A “convincing way” is a better criterion to consider. • A clear establishment of the new key is important, and usually a duration to the modulation of some length is required for this. • Understanding a modulation depends on the aural perception of the listener; hence, some ambiguity is inherent in distinguishing among a mere tonicization, a “false” modulation, and a modulation. • A modulation to a “foreign” key may be easier to accomplish than one to a diatonically related key: the ear is forced to interpret a new key quickly when there is a large change in the number of accidentals (i.e., the set of pitch classes) in the keys used. 1 Max Miller, “A First Step in Keyboard Modulation”, The American Organist, October 1982. 2 Charles S. Brown, CAGO Study Guide, 1981. 3 Janna Saslaw: “Modulation”, Grove Music Online ed. L. Macy (Accessed 5 May 2008), http://www.grovemusic.com. -

Development of Musical Scales in Europe

RABINDRA BHARATI UNIVERSITY VOCAL MUSIC DEPARTMENT COURSE - B.A. ( Compulsory Course ) (CBCS) 2020 Semester - II , Paper - I Teacher - Sri Partha Pratim Bhowmik History of Western Music Development of musical scales in Europe In the 8th century B.C., The musical atmosphere of ancient Greece introduced its development by the influence of then popular aristocratic music. That music was melody- based and the root of that music was rural folk-songs. In each and every country, the development of music was rooted in the folk-songs. The European Aristocratic Music of the Christian Era had been inspired by the developed Greek music. In the 5th century B.C. the renowned Greek Mathematician Pythagoras had first established a relation between science and music. Before him, the scale of Greek music was pentatonic. Pythagoras changed the scale into hexatonic pattern and later into heptatonic pattern. Greek musicians applied the alphabets to indicate the notes of their music. For the natural notes they used the alphabets in normal position and for the deformed notes, the alphabets turned upside down [deformed notes= Vikrita svaras]. The musical instruments, they had invented are – Aulos, Salpinx, pan-pipes, harp, lyre, syrinx etc. In the western music, the term ‘scale’ is derived from Latin word ‘scala’, ie, the ladder; scale means an ascent or descent formation of the musical notes. Each and every scale has a starting note, called ‘tonic note’ [‘tone - tonic’ not the Health-Tonic]. In the Ancient Greece, the musical scale had been formed with the help of lyre , a string instrument, having normally 5 or 6 or 7 strings. -

Many of Us Are Familiar with Popular Major Chord Progressions Like I–IV–V–I

Many of us are familiar with popular major chord progressions like I–IV–V–I. Now it’s time to delve into the exciting world of minor chords. Minor scales give flavor and emotion to a song, adding a level of musical depth that can make a mediocre song moving and distinct from others. Because so many of our favorite songs are in major keys, those that are in minor keys1 can stand out, and some musical styles like rock or jazz thrive on complex minor scales and harmonic wizardry. Minor chord progressions generally contain richer harmonic possibilities than the typical major progressions. Minor key songs frequently modulate to major and back to minor. Sometimes the same chord can appear as major and minor in the very same song! But this heady harmonic mix is nothing to be afraid of. By the end of this article, you’ll not only understand how minor chords are made, but you’ll know some common minor chord progressions, how to write them, and how to use them in your own music. With enough listening practice, you’ll be able to recognize minor chord progressions in songs almost instantly! Table of Contents: 1. A Tale of Two Tonalities 2. Major or Minor? 3. Chords in Minor Scales 4. The Top 3 Chords in Minor Progressions 5. Exercises in Minor 6. Writing Your Own Minor Chord Progressions 7. Your Minor Journey 1 https://www.musical-u.com/learn/the-ultimate-guide-to-minor-keys A Tale of Two Tonalities Western music is dominated by two tonalities: major and minor. -

10 - Pathways to Harmony, Chapter 1

Pathways to Harmony, Chapter 1. The Keyboard and Treble Clef Chapter 2. Bass Clef In this chapter you will: 1.Write bass clefs 2. Write some low notes 3. Match low notes on the keyboard with notes on the staff 4. Write eighth notes 5. Identify notes on ledger lines 6. Identify sharps and flats on the keyboard 7.Write sharps and flats on the staff 8. Write enharmonic equivalents date: 2.1 Write bass clefs • The symbol at the beginning of the above staff, , is an F or bass clef. • The F or bass clef says that the fourth line of the staff is the F below the piano’s middle C. This clef is used to write low notes. DRAW five bass clefs. After each clef, which itself includes two dots, put another dot on the F line. © Gilbert DeBenedetti - 10 - www.gmajormusictheory.org Pathways to Harmony, Chapter 1. The Keyboard and Treble Clef 2.2 Write some low notes •The notes on the spaces of a staff with bass clef starting from the bottom space are: A, C, E and G as in All Cows Eat Grass. •The notes on the lines of a staff with bass clef starting from the bottom line are: G, B, D, F and A as in Good Boys Do Fine Always. 1. IDENTIFY the notes in the song “This Old Man.” PLAY it. 2. WRITE the notes and bass clefs for the song, “Go Tell Aunt Rhodie” Q = quarter note H = half note W = whole note © Gilbert DeBenedetti - 11 - www.gmajormusictheory.org Pathways to Harmony, Chapter 1. -

Use of Scale Modeling for Architectural Acoustic Measurements

Gazi University Journal of Science Part B: Art, Humanities, Design And Planning GU J Sci Part:B 1(3):49-56 (2013) Use of Scale Modeling for Architectural Acoustic Measurements Ferhat ERÖZ 1,♠ 1 Atılım University, Department of Interior Architecture & Environmental Design Received: 09.07.2013 Accepted:01.10.2013 ABSTRACT In recent years, acoustic science and hearing has become important. Acoustic design tests used in acoustic devices is crucial. Sound propagation is a complex subject, especially inside enclosed spaces. From the 19th century on, the acoustic measurements and tests were carried out using modeling techniques that are based on room acoustic measurement parameters. In this study, the effects of architectural acoustic design of modeling techniques and acoustic parameters were investigated. In this context, the relationships and comparisons between physical, scale, and computer models were examined. Key words: Acoustic Modeling Techniques, Acoustics Project Design, Acoustic Parameters, Acoustic Measurement Techniques, Cavity Resonator. 1. INTRODUCTION (1877) “Theory of Sound”, acoustics was born as a science [1]. In the 20th century, especially in the second half, sound and noise concepts gained vast importance due to both A scientific context began to take shape with the technological and social advancements. As a result of theoretical sound studies of Prof. Wallace C. Sabine, these advancements, acoustic design, which falls in the who laid the foundations of architectural acoustics, science of acoustics, and the use of methods that are between 1898 and 1905. Modern acoustics started with related to the investigation of acoustic measurements, studies that were conducted by Sabine and auditory became important. Therefore, the science of acoustics quality was related to measurable and calculable gains more and more important every day.