The Problem of Archive Work in Christian Petzold's Phoenix

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bangor University DOCTOR of PHILOSOPHY Reimagining

Bangor University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Reimagining Everyday Life in the GDR Post-Ostalgia in Contemporary German Films and Museums Kreibich, Stefanie Award date: 2019 Awarding institution: Bangor University Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 Reimagining Everyday Life in the GDR: Post-Ostalgia in Contemporary German Films and Museums Stefanie Kreibich Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in Modern Languages Bangor University, School of Modern Languages and Cultures April 2018 Abstract In the last decade, everyday life in the GDR has undergone a mnemonic reappraisal following the Fortschreibung der Gedenkstättenkonzeption des Bundes in 2008. No longer a source of unreflective nostalgia for reactionaries, it is now being represented as a more nuanced entity that reflects the complexities of socialist society. The black and white narratives that shaped cultural memory of the GDR during the first fifteen years after the Wende have largely been replaced by more complicated tones of grey. -

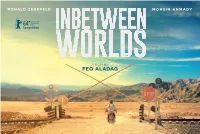

IBW Pressbook Print SCREEN.Pdf (4.4 Mib)

RONALD ZEHRFELD MOHSIN AHMADY A FILM BY FEO ALADAG SYNOPSIS German soldier Jesper signs up for a mission in Afghanistan, despite having lost his brother during an operation in the war-torn country. Jesper and his squad are assigned to protect a village outpost from increasing Taliban influence. With the help of young and inexperienced interpreter Tarik, Jesper seeks the trust of the local community and the allied Afghani militia. More than ever, he discovers the immense differences between the two worlds. When the lives of Tarik and his sister Nala are threatened by the Taliban, conflicted Jesper is torn between his military obligations and his conscience. COMMENTS FROM WRITER-DIRECTOR FEO ALADAG ORIGIN OF THE PROJECT was necessary for the highest authenticity in easy to find other producers to bring on board I remember my feelings looking at a newspaper environment, cast and atmosphere. I believe this and work on this film – at least not in Germany photograph showing a German soldier in always fuels the story and the environment you’re – since most were scared off by the risk, financial Afghanistan back in 2002/3. It seemed like an creating and always reflects back into the finished and otherwise, such a production does involve. entirely new image – a fighting German soldier output. It was also my hope that by working Such a production is vulnerable and dependent deployed in a war-torn country in combat together closely with an Afghani team and cast on daily events and politics. Everything can run uniform, fully armed. It made me think about and the Afghani officials who helped secure our smoothly on Monday, then suddenly Tuesday Germany’s attitude towards its military. -

Ours D'argent Festival De Berlin 2012 Prix De La Mise

PYRAMIDE PRÉSENTE NINA HOSS RONALD ZEHRFELD OURS D’ARGENT FESTIVAL DE BERLIN 2012 PRIX DE LA MISE EN SCÈNE UN FILM DE CHRISTIAN PETZOLD OURS D’ARGENT FESTIVAL DE BERLIN 2012 PYRAMIDE PRÉSENTE PRIX DE LA MISE EN SCÈNE NINA HOSS RONALD ZEHRFELD UN FILM DE CHRISTIAN PETZOLD RELATION PRESSE LES PIQUANTES ALEXANDRA FAUSSIER, FLORENCE ALEXANDRE & FANNY GARANCHER 27 RUE BLEUE - 75009 PARIS - 01 42 00 38 86 - [email protected] - WWW.LESPIQUANTES.COM DISTRIBUTION PYRAMIDE AU CINÉMA LE 2 MAI 5 RUE DU CHEVALIER DE SAINT GEORGE - 75008 PARIS - 01 42 96 01 01 DURÉE 105 MN PHOTOS ET DOSSIER DE PRESSE TÉLÉCHARGEABLES SUR WWW.PYRAMIDEFILMS.COM SYNOPSIS Eté 1980. Barbara est chirurgien-pédiatre dans un hôpital de Berlin-Est. Soupçonnée de vouloir passer à l’Ouest, elle est mutée par les autorités dans une clinique de province, au milieu de nulle part. Tandis que son amant Jörg, qui vit à l’Ouest, prépare son évasion, Barbara est troublée par l’attention que lui porte André, le médecin-chef de l’hôpital. La confiance professionnelle qu’il lui accorde, ses attentions, son sourire... Est-il amoureux d’elle ? Est-il chargé de l’espionner ? écrites au cordeau, qui semblent provoquées par cet environnement sous contrôle permanent. On comprend NOTE DU comment certaines circonstances peuvent engendrer des individus d’un genre nouveau qui s’embrassent, parlent et REALISATEUR se regardent d’une façon différente. Un autre film nous a impressionnés : LE MARCHAND DES CHRISTIAN PETZOLD QUATRE SAISONS de R.W. Fassbinder. L’Allemagne de l’Est des années 1950 est tellement présente dans ce film, du pare-brise arrière fendu d’une fourgonnette Volkswagen Bully aux bruits qui résonnent dans les arrière-cours désertes, en passant par l’espace exigu d’une cuisine en formica. -

Produktionsspiegel Regie Kamera Läuft Und Schnitt

KLAPPE, DIE ERSTE MV TiTEl Szene TIONSSPIEGEL Einstellung K U Nr. D RO P Kamera PRODUKTIONSSPIEGEL Regie Kamera läuft und Schnitt . Datum Filmproduktionen aus Mecklenburg-Vorpommern » TIONSSPIEGEL K U D RO P TiTEl Beide Teile an der gestrichelten Linie ausschneiden. START Nr. ENDE Einstellung Die Markierung für die Löcher Szene mit spitzem Gegenstand (z.B. Bleistift) durchbohren. Klappenteile übereinanderlegen und mit einer Musterklemme verbinden. Wenn beides nicht zur Hand ist, Kamera kann eine Büroklammer hilfreich sein. Regie Datum INHALT 3 Inhaltsverzeichnis . 3 Produktionsspiegel Black Death . 12 Vorwort/Interview/Essay Das Blaue vom Himmel . 14 Zwischen Werbung und Wirtschaftsfaktor . 5 DDR AHOI! . 16 Wer aufhört, neugierig zu sein, hört auf zu leben… . 6 Der Ghostwriter . 18 Mecklenburg-Vorpommern ist (noch) kein Filmland . 8 Der Kanal . 20 Deutschlands Küsten . 22 Die Grenze . 24 Über uns Die Männer der Emden . .. 26 filmlocationMV . 10 Die Vermessung der Welt . .28 Fünf Freunde . 30 Gesundheit DDR . .. 32 Produktionsspiegel 2009 – 2012 / Auswahl . 49 Luise - Königin der Herzen . 34 Impressum/Herausgeber . 74 Vergiss dein Ende . 36 Wadans Welt – Von der Würde der Arbeit . 38 Wunderkinder . 40 4 Tage im Mai . 42 12 Meter ohne Kopf . 44 4 © filmlocationMV Harry Glawe Vorwort Minister für Wirtschaft, Bau und Tourismus des Landes Mecklenburg-Vorpommern Zwischen Werbung und Wirtschaftsfaktor − Wofür brauchen wir den Film im Land? VORWORT 5 Schöne Strände, klare Seen und gesunde Wälder – ja, Dass Filmproduktionen auf unser Land aufmerksam werden, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern ist bekannt als Land für Urlaub und ist noch kein Selbstläufer . Hier bedarf es professioneller Unter- Erholung . Dass dies bei den Menschen ankommt, stützung . Das Wirtschaftministerium unterstützt deshalb die davon zeugen mehrere Millionen Besucher pro Jahr in unserem Einrichtung eines Drehortservice . -

Presskit SHORES of HOPE

presents A film by Toke Constantin Hebbeln Starring Alexander Fehling, August Diehl, Ronald Zehrfeld Produced by UFA Cinema and Frisbeefilms in co-production with BR, Degeto, SWR, BR/arte and SR as well as Hahn Film in cooperation with CinePostproduction Supported by Medienboard Berlin-Brandenburg, FilmFernsehFonds Bayern, Film- und Medienstiftung Nordrhein-Westfalen, FilmFörderung Saarland, Deutschen Filmförderfonds Cast Cornelis Schmidt Alexander Fehling Andreas Hornung August Diehl Phuong Mai Phuong Thao Vu Matthias Schönherr Ronald Zehrfeld Sabine Schönherr Annika Blendl Roman Sylvester Groth Oberst Seler Rolf Hoppe Ralfi Hans-Uwe Bauer Eberhard Fromm Thomas Lawinky Crew Director Toke Constantin Hebbeln Scriptwriters Ronny Schalk, Toke Constantin Hebbeln Cinematographer Felix Novo de Oliveira Producers Nico Hofmann, Ariane Krampe, Jürgen Schuster, Manuel Bickenbach, Alexander Bickenbach Executive Producer Sebastian Werninger Co-Producers Bettina Reitz, Hans-Wolfgang Jurgan Producer Hahn Film Herbert Gehr Supervisors Birgit Metz (BR) Ulrich Herrmann (SWR) Jochen Kölsch (BR/ARTE) Monika Lobkowicz (BR/ARTE) Andreas Schreitmüller (ARTE) Christian Bauer (SR) Sets Lars Lange Costumes Judith Holste Original Sound Erich Lutz Editor Simon Blasi Music Nic Raine German Release: 13 Sept 2012 by Wild Bunch Germany For further information: 2 Beta Cinema GmbH, Press, Dorothee Stoewahse, Tel: + 49 89 67 34 69 15, Mobile: + 49 170 63 84 627 [email protected] , www.betacinema.com . Pictures and filmclips available on ftp.betafilm.com , username: ftppress01, -

Ronald Zehrfeld Vita

Ronald Zehrfeld Vita Sophienstr. 21 10178 Berlin Fon +49 (0)30 285168-0 Fax +49 (0)30 285168-6 [email protected] Ronald Zehrfeld 2/8 2021 WARTEN AUF’N BUS 2. STAFFEL series , directed by: Fabian Möhrke BABYLON BERLIN series , directed by: Achim von Borries, Henk Handloegten, Tom Tykwer 2020 DENGLER – KREUZBERG BLUES tv movie , directed by: Daniel Rübesam DIE SCHWARZE SPINNE cinema , directed by: Markus Fischer TATORT – DER FEINE GEIST tv movie , directed by: Mira Thiel 2019 WARTEN AUF’N BUS series , directed by: Dirk Kummer ALLE REDEN ÜBERS WETTER cinema , directed by: Annika Pinske BABYLON BERLIN SEASON 3 series , directed by: Achim von Borries, Henk Handloegten, Tom Tykwer WALPURGISNACHT mini series , directed by: Hans Steinbichler 23.09.2021 Ronald Zehrfeld 3/8 2018 BAUHAUS series , directed by: Lars Kraume DAS ENDE DER WAHRHEIT cinema , directed by: Philipp Leinemann BIST DU GLÜCKLICH tv movie , directed by: Max Zähle SWEETHEARTS cinema , directed by: Karoline Herfurth WAS GEWESEN WÄRE cinema , directed by: Florian Koerner von Gustorf HACKERVILLE mini series , directed by: Anca Miruna Lazarescu DENGLER – BRENNENDE KÄLTE tv movie , directed by: Rick Ostermann 2017 DAS DRITTE STERBEN cinema , directed by: Philipp Leinemann DAS SCHWEIGENDE KLASSENZIMMER cinema , directed by: Lars Kraume DENGLER – FREMDE WASSER tv movie , directed by: Rick Ostermann 23.09.2021 Ronald Zehrfeld 4/8 2016 LANDGERICHT tv movie , directed by: Matthias Glasner Grimme-Preis - Beste Darstellung NEBEN DER SPUR tv movie , directed by: Anno Saul DENGLER – DIE SCHÜTZENDE -

Das Schweigende Klassenzimmer

KINOSTART: 19. April Verleih Presse LOOK NOW! – 8005 Zürich Prosa Film – Rosa Maino Tel: 044 440 25 44 [email protected] [email protected] – www.looknow.ch office 044 296 80 60 – mobile 079 409 46 04 BESETZUNG Theo Lemke Leonard Scheicher Kurt Wächter Tom Gramenz Lena Lena Klenke Erik Babinski Jonas Dassler Paul lsaiah Michalski Hermann Lemke Ronald Zehrfeld Ingrid Lemke Carina Wiese Rektor Schwarz Florian Lukas Frau Kessler Jördis Triebel FDJ-Sekretär Ringel Daniel Krauss Edgar Michael Gwisdek Volksbildungsminister Lange Burghart Klaussner Hans Wächter Max Hopp Anna Wächter Judith Engel Pfarrer Melzer Götz Schubert STAB Regie & Drehbuch Lars Kraume Kamera Jens Harant Szenenbild Olaf Schiefner Kostümbild Esther Walz Maskenbild Jens Bartram und Judith Müller Ton Stefan Soltau Schnitt Barbara Gies Casting Nessi Nesslauer Produzentin Miriam Düssel, Akzente Film & Fernsehproduktion Executive Producer Susanne Freyer, Akzente Film & Fernsehproduktion Koproduzenten ZDF (Caroline von Senden), Zero One Film (Thomas Kufus), STUDIOCANAL Film (Kalle Friz & lsabel Hund) TECHNISCHE DATEN Lauflänge: 111 Min. Format: Cinemascope - DCP Ton: Dolby 5.1. Sprache: Deutsch (oder D/f UT) VERLEIH LOOK NOW! Filmdistribution – Gasometerstrasse 9 – 8005 Zürich – [email protected] – www.looknow.ch SYNOPSIS Ein grossartiges Ensemble von jungen Schauspielern vereinigt sich zu den 19 Schülern einer Abitur-klasse, die 1956 mit einer einfachen menschlichen Geste einen ganzen Staatsapparat gegen sich aufbrachte – eingeschlossen in einem Staat, der 5 Jahre später mit dem Bau der Mauer ganz dicht machte, wurden die Schüler vor eine Entscheidung gestellt, die dramatische Folgen für ihre Zukunft und die ihrer Familien hat. Eine packende und wahre Geschichte über den aussergewöhnlichen Mut Einzelner in einer Zeit der politischen Unterdrückung. -

Phoenix Medienpädagogisches Begleitheft

1 Medienpädagogisches Begleitheft _ PHOENIX 2 Medienpädagogisches Begleitheft _ PHOENIX PHOENIX Deutschland 2014 Länge: 98 Min. Format: 35mm/DCP, Cinemascope Regie: Christian Petzold Drehbuch: Christian Petzold, unter Mitarbeit von Harun Farocki, nach Motiven des Romans „Der Asche entstiegen“ („Le retour des cendres“) von Hubert Monteilhet Bildgestaltung: Hans Fromm Montage: Bettina Böhler Kostümbild: Anette Guther Szenenbild: K.D. Gruber Sound Design: Dominik Schleier Musik: Stefan Will sowie Kurt Weill, Antonio Vivaldi, Holger Hiller, Cole Porter Darsteller: Nina Hoss (Nelly Lenz), Ronald Zehrfeld (Johnny Lenz), Nina Kunzendorf (Lene Winter), Michael Maertens (Arzt), Kirsten Block (Wirtin) u. a. Produktion: SCHRAMM FILM Koerner & Weber, in Zusammenarbeit mit Tempus Film, in Koproduktion mit dem BR, dem WDR und ARTE Filmverleih: Piffl Medien GmbH, Berlin FBW: „besonders wertvoll“ FSK: ab 12 J. Empfohlen: ab 9. Jahrgangsstufe Themen: (Deutsche) Geschichte, Holocaust, Nationalsozialismus, Nachkriegszeit („Stunde Null“), Rassismus, Identität, Liebe, Menschenrechte/-würde, Schuld und Verdrängung, Vorurteile Lehrplanbezüge (fächerübergreifend): Deutsche Geschichte (Holocaust, Nachkriegszeit, Displaced Persons) Religion/ Ethik (Schuld und Verantwortung, Vergebung) Medienkunde (Filmisches Erzählen, Literaturverfilmung, filmsprachliche Mittel …) Musik (Kurt Weill) 3 Medienpädagogisches Begleitheft _ PHOENIX Inhalt Im Juni 1945 wird die jüdische Sängerin Nelly Lenz schwer verletzt und mit zerstörtem Gesicht von ihrer langjährigen Freundin Lene Winter, einer Mitarbeiterin der Jewish Agency, in die alte Heimat Berlin gebracht. Nelly hat wie durch ein Wunder das Konzentrationslager Auschwitz-Birkenau überlebt. Nach Nellys erfolgreich verlaufener Gesichtsoperation hofft Lene, mit Nelly nach Palästina auswandern zu können. Doch allen ihren Warnungen zum Trotz macht sich Nelly auf die Suche nach ihrem geliebten Ehemann Johnny, der ihr bis 1944 ein Überleben in Deutschland ermöglichte. Als sie ihn endlich im Nachtclub Phoenix findet, scheint Johnny sie nicht zu erkennen. -

Barbara Presseheft Engl 01 L

A FILM BY CHRISTIAN PETZOLD THE MATCH FACTORY PRESENTS ASCHRAMM FILM KOERNER&WEBER PRODUCTIONIN COPRODUCTION WITH ZDF ANDARTE ‘BARBARA’ WITHNINA HOSS RONALD ZEHRFELD JASNA FRITZI BAUER MARK WASCHKE RAINER BOCK CHRISTINA HECKE ROSA ENSKAT SUSANNE BORMANN PETER BENEDICT THOMAS NEUMANN KIRSTEN BLOCK ET. AL. DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY HANS FROMM BVK EDITOR BETTINA BÖHLER PRODUCTION DESIGN K.D. GRUBER COSTUME DESIGN ANETTE GUTHER MAKE UP BARBARA KREUZER ALEXANDRA LEBEDYNSKI SOUND ANDREAS MÜCKE-NIESYTKA SCRIPT ASSISTANT PRODUCTION SOUND MIX MARTIN STEYER MUSICSTEFAN WILL CASTINGSIMONE BÄR CONSULTANT HARUN FAROCKI DIRECTOR IRES JUNG MANAGER DORISSA BERNINGER COMMISSIONING EDITORS CAROLINE VON SENDEN ANNE EVEN ANDREAS SCHREITMÜLLER PRODUCER FLORIAN KOERNER VON GUSTORF MICHAEL WEBER WRITTEN & DIRECTED BY CHRISTIAN PETZOLD FUNDED BY MEDIENBOARD BERLIN-BRANDENBURG BKM FFA DFFF WORLD SALESTHE MATCH FACTORY Nina Hoss (Barbara) BARBARA A Film by Christian Petzold Barbara Nina Hoss Casting Simone Bär Andre Ronald Zehrfeld Script Consultant Harun Farocki Stella Jasna Fritzi Bauer Assistant Director Ires Jung Jörg Mark Waschke Production Manager Dorissa Berninger Schütz Rainer Bock Producer Florian Koerner von Gustorf Michael Weber Director of Photography Hans Fromm BVK Written & Directed by Christian Petzold Editor Bettina Böhler Production Design K.D. Gruber Costume Design Anette Guther A Schramm Film Koerner&Weber Production in coproduction Make Up Barbara Kreuzer with ZDF and ARTE. Funded by Medienboard Berlin-Branden- Alexandra Lebedynski burg, BKM, FFA, DFFF. World Sales THE MATCH FACTORY Sound Andreas Mücke-Niesytka Sound Mix Martin Steyer Music Stefan Will D 2012 | 105 min | 24fps | 35mm / DCP | 1:1,85 | Dolby Digital 2 Ronald Zehrfeld (Andre), Rainer Bock (Schütz) DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT In the films of recent years, East Germany has often appeared emptiness of a bare backyard, in the cramped confines of a for- quite desaturated. -

Films De Fiction Allemands Sur Dvd

FILMS DE FICTION ALLEMANDS SUR DVD DISPONIBLES A LA BIBLIOTHEQUE -A- Absolute Giganten / R : Sebastian Schipper. – A : Frank Giering, Florian Lucas, Antoine Monot Jr. – 1999, 81 min. Dans une ville en périphérie de Hambourg, Floyd fête ses adieux avec ses deux amis. Le lendemain, Floyd commencera son travail sur un bateau. Les trois amis font la tournée des bars de la ville. Le film raconte leurs expériences apparemment fortuites, les prudentes avancées dans la vie, la fuite devant l'immobilité, les nouvelles possibilités qui s'offrent aux jeunes gens. La critique sociale telle qu'elle était pratiquée il y a plusieurs décennies, a fait place à un style de narration fortement enjoué. Cote : GI 791 ABS Absurdistan / R : Houchang Allahyari. – A : Julia Stemberger, Karl Markovics, Meltem Cumbul. – 2008, 89 min. Un minuscule village, quelque part en Asie centrale. Un jour, les canalisations d'eau vétustes éclatent. Les femmes, fatiguées de voir leurs maris jouer aux cartes plutôt que de s'occuper du problème, décrètent une grève du sexe. Cote : GI 791 AS After Spring comes Fall / R: Daniel Carsenty. – A: Halima Ilter, Tamer Yigit, Asad Schwarz, Murat Seven u.a. – 2014/15, 90 min. La jeune kurde Mina décide de quitter son pays, la Syrie, pour se réfugier à Berlin. Elle commence une nouvelle vie sous l’apparente protection de l’illégalité. Elle transfère régulièrement de l’argent à sa famille, et ce sont précisément ces transferts qui vont lui être funestes. Les services secrets syriens la repèrent et la forcent à collaborer comme indicateur. Cote : GI 791 AF Agnes und seine Brüder (Agnes et ses frères) / R : Oskar Röhler. -

Il Segreto Del Suo Volto (Phoenix)

IL SEGRETO DEL SUO VOLTO (PHOENIX) un film di Christian Petzold con Nina Hoss Ronald Zehrfeld Nina Kunzendorf durata 98 minuti Via Lorenzo Magalotti 15, 00197 ROMA Tel. 06-3231057 Fax 06-3211984 1 ufficio stampa Federica de Sanctis 335 1548137 [email protected] I materiali stampa sono scaricabili dall’area press del sito www.bimfilm.com SINOSSI Giugno 1945. Sopravvissuta al campo di sterminio di Auschwitz, Nelly torna a Berlino, dov’è nata, gravemente ferita e col volto sfigurato. Ad accompagnarla c’è Lene, impiegata dell’Agenzia ebraica e amica di Nelly da prima della guerra. Senza neppure aspettare di essersi ripresa dall’intervento di chirurgia plastica al viso, e contro il parere di Lene, Nelly parte alla ricerca di suo marito, Johnny: l’uomo che ha cercato fino alla fine di proteggerla dalla persecuzione nazista. I familiari di Nelly sono tutti morti nell’olocausto. Johnny è convinto che anche sua moglie sia morta. Quando finalmente Nelly lo rintraccia, Johnny intravede solo una vaga somiglianza e non crede che possa trattarsi veramente di sua moglie. Per mettere al sicuro l’eredità della famiglia di lei, però, Johnny propone a Nelly di assumere l’identità della moglie morta. Nelly accetta e diventa l’impostora di se stessa. Vuole sapere se Johnny l’amava veramente, e se l’ha tradita. Vuole riprendersi la sua vita. 2 CHRISTIAN PETZOLD - Sceneggiatore, regista Nato nel 1960 a Hilden, in Germania, Petzold ha studiato prima letteratura tedesca e teatro alla Freie Universität Berlin (Libera Università di Berlino); e poi regia cinematografica al DFFB (Accademia del Cinema e della Televisione di Berlino). -

KINOSTART 5. DEZEMBER Stadtkino Filmverleih Spittelberggasse 3/3

KINOSTART 5. DEZEMBER Stadtkino Filmverleih Tel. 01 522 48 14 Spittelberggasse 3/3, 1070 Wien [email protected] REGIE-STATEMENT Der erste Drehtag von „Phoenix“: Ein Birkenwäldchen, ein Mann in Wehrmachtsuniform, Frauen in KZ-Kleidung. Als Vorlage hatte uns ein Bild der Shoa-Foundation gedient, in grobkörniger Farbe, eine Waldkreuzung in einem impressionistischen Morgenlicht – und erst auf den zweiten Blick darin der Tod, die Leichen im Gras. Schon beim Drehen haben wir gemerkt, dass etwas nicht stimmte. Das Licht war gut, die Kadragen klar, das Bild schien uns auf präzise Art nachgestellt. Aber es ging nicht. Das Nachstellen des Schreckens, die Kinematographie in und um Auschwitz– als würden wir sagen: Jetzt ist es Zeit, jetzt fassen wir das alles als Erzählung zusammen, jetzt wird es eine Ordnung. Das Material vom ersten Drehtag haben wir weggeschmissen. Raul Hilberg hat geschrieben, dass sich der Terror der Nazis und der anhänglichen Bevölkerung im Grunde aus Techniken speiste, die lange bekannt waren. Das Neue, das waren die Vernichtungslager, die industrielle Vernichtung der Menschen. Für die alten Techniken gab es noch Literatur, Erzählungen, Gesänge. Für den Holocaust gibt es sie nicht mehr. Ein Text, der uns in der Vorbereitung sehr beeindruckt hat, war „Ein Liebesversuch“ von Alexander Kluge. Die Geschichte spielt in Auschwitz, die Nazis schauen durch Beobachtungsschlitze einem Paar in einem geschlossenen Raum zu, das sich einmal leidenschaftlich geliebt hat, so steht es in den Akten. Die Naziärzte versuchen diese Liebe wieder zu erwecken. Das Paar soll miteinander schlafen. Es soll verifiziert werden, ob die Sterilisation der Frau erfolgreich war. Man versucht alles: Champagner, rotes Licht, das Abspritzen mit eiskaltem Wasser, so dass vielleicht das Wärmebedürfnis die beiden wieder zusammenführt.