Librarians and Book Collectors: Friends and Foes1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Incunabula and Sixteenth Century Imprints

Incunabula and Sixteenth Century Imprints FREDERICK R. GOFF THEWISE preacher in the Book of Ecclesiastes in- formed his listeners that “Of the making of many books there is no end.” If this was true in early Biblical times, one can only imagine what this learned gentleman’s appalled reaction would be to the pro- digious and continuous outpouring from the contemporary press. No one will ever be able to estimate the number of books that have been produced since those anonymous pressmen, working for Gutenberg, commenced to pull sheets from the presses he had constructed for his first printing office. It is possible, however, to estimate in rough fash- ion the number of books, pamphlets, and broadsides that issued dur- ing the period of incunabular printing that, with some questionable exceptions, ended with the commencement of the year 1501. There is valid evidence to support an estimate of upwards of 40,000 editions that were printed on the earliest European presses at work during the first fifty years after the invention of printing with movable metal types. If, as we have reason to believe, the average number of copies produced in a fifteenth-century edition was 500, these early printers were responsible for placing in circulation approximately 20,000,000 books, pamphlets, and broadsides. There are no accurate statistics to determine how many of this original estimate survive today, but it is a matter of record that ac- cording to the statistical survey made during the compilation of the Third Census of Zncunabula in American Libraries, compiled and edited by this writer, and published by the Bibliographical Society of America in 1964 (New York), 47,188 copies of 12,599 editions were recorded in American ownership, How many other copies of incunabula have survived is a matter of interesting speculation. -

Collectorz.Com Book Collector Help Manual

Collectorz.com Book Collector Help Manual © 2008 Bitz & Pixelz BV 2 Collectorz.com Book Collector Help Manual Table of Contents Foreword 0 Part I Introduction 5 Part II Find answers in the manual 6 Part III Getting started 10 1 Getting Started................................................................................................................................... - Your first 10 clicks 11 2 Getting Started................................................................................................................................... - Adding your first book 13 3 Getting Started................................................................................................................................... - Quick Guide 14 4 Getting Started................................................................................................................................... - Useful and powerful tips 17 Part IV Buying Book Collector 19 Part V Support 22 Part VI Common Tasks 22 1 Adding Books................................................................................................................................... Automatically - Using the queue 24 2 Editing books................................................................................................................................... 25 3 Browsing your................................................................................................................................... database 29 4 Finding a book.................................................................................................................................. -

A Book Lover's Journey: Literary Archaeology and Bibliophilia in Tim

Verbeia Número 1 ISSN 2444-1333 Leonor María Martínez Serrano A Book Lover’s Journey: Literary Archaeology and Bibliophilia in Tim Bowling’s In the Suicide’s Library Leonor María Martínez Serrano Universidad de Córdoba [email protected] Resumen Nativo de la costa occidental de Canadá, Tim Bowling es uno de los autores canadienses más aclamados. Su obra In the Suicide’s Library. A Book Lover’s Journey (2010) explora cómo un solo objeto —un ejemplar gastado ya por el tiempo de Ideas of Order de Wallace Stevens que se encuentra en una biblioteca universitaria— es capaz de hacer el pasado visible y tangible en su pura materialidad. En la solapa delantera del libro de Stevens, Bowling descubre la elegante firma de su anterior dueño, Weldon Kees, un oscuro poeta norteamericano que puso fin a su vida saltando al vacío desde el Golden Gate Bridge. El hallazgo de este ejemplar autografiado de la obra maestra de Stevens marca el comienzo de una meditación lírica por parte de Bowling sobre los libros como objetos de arte, sobre el suicidio, la relación entre padres e hijas, la historia de la imprenta y la bibliofilia, a la par que lleva a cabo una suerte de arqueología del pasado literario de los Estados Unidos con una gran pericia literaria y poética vehemencia. Palabras clave: Tim Bowling, bibliofilia, narrativa, arqueología del saber, vestigio. Abstract A native of the Canadian West Coast, Tim Bowling is widely acclaimed as one of the best living Canadian authors. His creative work entitled In the Suicide’s Library. A Book Lover’s Journey (2010) explores how a single object —a tattered copy of Wallace Stevens’s Ideas of Order that he finds in a university library— can render the past visible and tangible in its pure materiality. -

![Willa Cather, “My First Novels [There Were Two]”, and the Colophon: a Book Collector’S Quarterly](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4608/willa-cather-my-first-novels-there-were-two-and-the-colophon-a-book-collector-s-quarterly-784608.webp)

Willa Cather, “My First Novels [There Were Two]”, and the Colophon: a Book Collector’S Quarterly

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Digital Initiatives & Special Collections Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln Fall 10-26-2012 Material Memory: Willa Cather, “My First Novels [There Were Two]”, and The Colophon: A Book Collector’s Quarterly Matthew J. Lavin University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/librarydisc Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons Lavin, Matthew J., "Material Memory: Willa Cather, “My First Novels [There Were Two]”, and The Colophon: A Book Collector’s Quarterly" (2012). Digital Initiatives & Special Collections. 4. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/librarydisc/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digital Initiatives & Special Collections by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Material Memory: Willa Cather, “My First Novels [There Were Two]”, and The Colophon: A Book Collector’s Quarterly Introduction Willa Cather’s 1931 essay “My First Novels [There Were Two]” occupies a distinct position in Cather scholarship. Along with essays like “The Novel Démeublé” and “On The Professor’s House ” it is routinely invoked to established a handful of central details about the writer and her emerging career. It is enlisted most often to support the degree to which Cather distanced herself from her first novel Alexander’s Bridge and established her second novel O Pioneers! As a sort of second first novel, the novel in which she first found her voice by writing about the Nebraska prairie and its people. -

The Antiquarian Bookmarket and the Acquisition of Rare Books

The Antiquarian Bookmarket and the Acquisition of Rare Books DONALD G. WING and ROBERT VOSPER IN ONLY A FEW CASES is the acquisition of gen- eral out-of-print and of rare books identical. Usually two different ap- proaches and two different types of dealers or private owners are involved. One of the most frequent headaches is the little old lady who comes in off the street and expects that because her book is old (to her) it must be rare. It seems-entirely reasonable to throw away most of what is so carefully preserved in safe deposit boxes and replace this with pamphlets and broadsides all too frequently carelessly for- gotten in attics. Few family Bibles are of value beyond the immediate family, and eighteenth century German prayer books seldom budge the purse strings of order librarians. Occasionally there will be a local historical society that will accept Bibles with genealogical entries, if they are of local interest. Otherwise, that Bible, with the immigrant ancestor's other forms of piety, had better be handed on to another member of the family, less cramped for space than a library. The late Rumball-Petrel had something to say on this particular matter. Effectiveness in both kinds of antiquarian buying, general out-of- print and rare books, is crucial to the health of any library. And neither is too well understood by librarians. It is a rare library school teacher who mentions the matter, and too little is written on the sub- ject. The only way to find out, given imagination and an enthusiastic flair for the work, is to learn on the job in a good library or a bookstore, or both, to read dealers' catalogs and the other literature of the trade assiduously, to talk with dealers and collectors, or better yet listen to them, and, most of all, to be in love with the excitement of books, bibliography, and the book trade. -

Romantic Bibliomania: Authorship, Identity, and the Book Alys

Romantic Bibliomania: Authorship, Identity, and the Book Alys Elizabeth Mostyn Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of English June 2014 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. © 2014 The University of Leeds and Alys Elizabeth Mostyn The right of Alys Elizabeth Mostyn to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. i Acknowledgements Thanks must first go to the Arts and Humanities Research Council UK for providing the funding for this doctoral thesis, without which it would not have been possible. I am also grateful to the British Association of Romantic Studies for the award of a Stephen Copley Postgraduate Research Bursary, which allowed me to undertake archival research crucial to the completion of my second chapter. My supervisor, John Whale, has my gratitude for his continued support, both intellectual and collegial. This thesis is the direct result of his tutelage, from undergraduate level onwards. My obsession with the labyrinthine prose of Thomas De Quincey would not exist without him; whether that is a good thing or not, I do not know! Other colleagues at the University of Leeds have made undertaking a PhD here an enjoyable and enlightening experience. -

Exploring Representations of Early Modern German Women Book Collectors (1650-1780)

CURATING THE COLLECTOR: EXPLORING REPRESENTATIONS OF EARLY MODERN GERMAN WOMEN BOOK COLLECTORS (1650-1780) BY KATHLEEN MARIE SMITH DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in German in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2012 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Mara R. Wade, Chair Associate Professor Laurie Johnson Associate Professor Stephanie Hilger Professor Carl Niekerk Professor Tom D. Kilton, Emeritus ABSTRACT This dissertation examines representations of book collecting by German women in the early modern period in order to explore the role of gender in this activity. Portrayals of book collectors in the modern and early modern eras offer examples of how this identity is constructed, particularly in the underlying assumptions and expectations that determine who is defined as a book collector and what criteria are used to shape that decision. In the case of four early modern women--Elisabeth Sophie Marie of Braunschweig-Lüneburg (1683-1767); Elisabeth Ernestine Antonie of Sachsen-Meiningen (1681-1766); Caroline of Ansbach (1683- 1737); and Wilhelmine of Bayreuth (1709-1758)--the act of collecting is depicted as essential to their social status and an integral part of their lives. Finally, in an in-depth case study of an early modern German woman who was a book collector, Sophie of Hanover (1630-1714), this study analyzes how she represented her collecting activities and textual interaction as well as how she is represented in other texts. The way in which these early modern German women were represented and represented themselves as collectors reveals a great deal about the position of women within wider networks concerning the exchange of texts and information. -

William Blake the Book of Urizen London, Ca

® about this book O William Blake The Book of Urizen London, ca. 1818 ➤ Commentary by Nicolas Barker ➤ Binding & Collation ➤ Provenance ©2001 Octavo. All rights reserved. The Book of Urizen Commentary by Nicolas Barker The Book of Urizen, originally entitled The First Book of Urizen, occupies a central place in William Blake’s creation of his “illuminated books,” both chronologically and in the thematic and structural development of the texts. They are not “illuminated” in the sense that medieval manuscripts are illu- minated—that is, with pictures or decoration added to an exist- ing text. In Blake’s books, text and decoration were conceived together and the printing process, making and printing the plates, did not separate them, although he might vary the colors from copy to copy, adding supplemen- tary coloring as well. Like the books themselves, the technique for making them came to Blake by inspiration, connected with his much-loved younger brother Robert, whose early death in 1787 deeply distressed William, though his “visionary eyes beheld the released spirit ascend heaven- ward through the matter-of-fact Plate 26 of The Book of Urizen, copy G (ca. 1818). ceiling, ‘clapping its hands for joy.’” The process was described by his fellow- engraver John Thomas Smith, who had known Robert as a boy: After deeply perplexing himself as to the mode of accomplishing the publication of his illustrated songs, without their being subject to the expense of letter-press, his brother Robert stood before him in one of his visionary imaginations, and so decidedly directed him in the way in which he ought to proceed, that he immediately fol- lowed his advice, by writing his poetry, and drawing his marginal subjects of embellishments in outline upon the copperplate with an impervious liquid, and then eating the plain parts or lights away William Blake The Book of Urizen London, ca. -

Robert Darnton, “What Is the History of Books?”

What is the History of Books? The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Darnton, Robert. 1982. What is the history of books? Daedalus 111(3): 65-83. Published Version http://www.jstor.org/stable/20024803 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:3403038 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA ROBERT DARNTON What Is the History of Books? "Histoire du livre" in France, "Geschichte des Buchwesens" in Germany, "history of books" or "of the book" in English-speaking countries?its name varies from to as an new place place, but everywhere it is being recognized important even discipline. It might be called the social and cultural history of communica were not a to tion by print, if that such mouthful, because its purpose is were understand how ideas transmitted through print and how exposure to the printed word affected the thought and behavior of mankind during the last five hundred years. Some book historians pursue their subject deep into the period on before the invention of movable type. Some students of printing concentrate newspapers, broadsides, and other forms besides the book. The field can be most concerns extended and expanded inmany ways; but for the part, it books an area so since the time of Gutenberg, of research that has developed rapidly seems to a during the last few years, that it likely win place alongside fields like art canon the history of science and the history of in the of scholarly disciplines. -

Nostalgia and the Physical Book

NOSTALGIA AND THE PHYSICAL BOOK Cheyenne White A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2021 Committee: Kristen Rudisill, Advisor Esther Clinton © 2021 Cheyenne White All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Kristen Rudisill, Advisor We are used to seeing books, handling them, reading them, but we are not so used to analyzing our relationship to the form of the object, yet in this thesis, I argue that the very shape and composition of books has an impact on our interactions and relationships with them. By looking at the material book, we must confront the cultural, social, and individual significance that these material objects are imbued with. The physical attributes of books, from the smell of ink and paper to the distinct feel of a hefty hardback or flexible paperback, contribute specific things to culture and an individual’s experience as physical books carry commercial, aesthetic, and emotional value. By looking at material culture studies, memory and commemoration, as well as theory behind nostalgia, I argue that the physical book can be both a powerful object and carrier of social meaning by utilizing Grant McCracken’s notion of displaced meaning, academic studies of nostalgia, the science of book scent, bookshop curation, and book collecting, along with essay compilations by booklovers. From the affective power of the sensory aspects of books to book collecting and book spaces, the materiality of the book is revealed not as a mere vessel for texts but as essential to the physical book’s ability to anchor memory, emotion, and identity. -

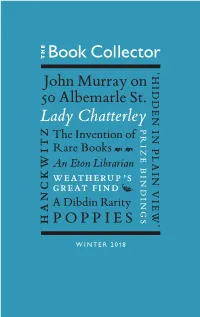

The-Book-Collector-Example-2018-04.Pdf

641 blackwell’s blackwell’s rare books rare48-51 Broad books Street, 48-51 Broad Street, 48-51Oxford, Broad OX1 Street, 3BQ Oxford, OX1 3BQ CataloguesOxford, OX1 on 3BQrequest Catalogues on request CataloguesGeneral and subject on catalogues request issued GeneralRecent and subject subject catalogues catalogues include issued General and subject catalogues issued blackwellRecentModernisms, subject catalogues Sciences, include ’s Recent subject catalogues include blackwellandModernisms, Greek & Latin Sciences, Classics ’s rareandModernisms, Greek &books Latin Sciences, Classics rareand Greek &books Latin Classics 48-51 Broad Street, 48-51Oxford, Broad OX1 Street, 3BQ Oxford, OX1 3BQ Catalogues on request Catalogues on request General and subject catalogues issued GeneralRecent and subject subject catalogues catalogues include issued RecentModernisms, subject catalogues Sciences, include andModernisms, Greek & Latin Sciences, Classics and Greek & Latin Classics 641 APPRAISERS APPRAISERS CONSULTANTS CONSULTANTS 642 Luis de Lucena, Repetición de amores, y Arte de ajedres, first edition of the earliest extant manual of modern chess, Salamanca, circa 1496-97. Sold March 2018 for $68,750. Accepting Consignments for Autumn 2018 Auctions Early Printing • Medicine & Science • Travel & Exploration • Art & Architecture 19th & 20th Century Literature • Private Press & Illustrated Americana & African Americana • Autographs • Maps & Atlases [email protected] 104 East 25th Street New York, NY 10010 212 254 4710 SWANNGALLERIES.COM 643 Heribert Tenschert -

A Handsome Quarterly, in Print and Online, For

the Book Collector Mania and Imagination fencers treading upon ice A Venice Collection LANE STANLEY News Sales, Catalogues, & Exhibitions pThe Friends of & Arthur Machen Comment A State of _ _ WAD DEAbsolute S D O N Rarity n A BINDING FOR MATTHEW PARKER BY JEAN DE PLANCHE A.T. Bartholomew: a life through books AUTUMN 2016 blackwell’s rareblackwell books’s rare books 48-51 Broad Street, 48-51 Broad Street, 48-51Oxford, Broad OX1 Street, 3BQ Oxford, OX1 3BQ CataloguesOxford, OX1 on 3BQrequest Catalogues on request General and subject catalogues issued GeneralRecent and subject subject catalogues catalogues include issued GeneralRecent and subject subject catalogues catalogues include issued blackwellRecentModernisms, subject catalogues Sciences, include ’s RecentModernisms, subject catalogues Sciences, include blackwellandModernisms, Greek & Latin Sciences, Classics ’s andModernisms, Greek & Latin Sciences, Classics rareand Greek &books Latin Classics rareand Greek &books Latin Classics 48-51 Broad Street, 48-51Oxford, Broad OX1 Street, 3BQ Oxford, OX1 3BQ Catalogues on request Catalogues on request General and subject catalogues issued GeneralRecent and subject subject catalogues catalogues include issued RecentModernisms, subject catalogues Sciences, include andModernisms, Greek & Latin Sciences, Classics and Greek & Latin Classics 349 APPRAISERS APPRAISERS CONSULTANTS CONSULTANTS 350 GianCarLo PEtrELLa À la chasseGianCarL oau PEtr bonheurELLa I libri ritrovatiGianCar diLo Renzo PEtrELL Bonfigliolia À la chassee altri auepisodi bonheur ÀdiI libri lastoria ritrovatichasse del collezionismo di auRenzo bonheur Bonfiglioli italiano e altri episodi I libri ritrovatidel Novecento di Renzo Bonfiglioli di storia del collezionismo italiano Presentazionee altri di Dennisepisodi E. Rhodes del Novecento di storia del collezionismo italiano In 1963, Presentazionethe untimelydel Novecento di Dennis E.Johannes Rhodes Petri, c.