Execution of MIMD MIPSEL Assembly Programs Within CUDA/Opencl Gpus Henry G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CUDA by Example

CUDA by Example AN INTRODUCTION TO GENERAL-PURPOSE GPU PROGRAMMING JASON SaNDERS EDWARD KANDROT Upper Saddle River, NJ • Boston • Indianapolis • San Francisco New York • Toronto • Montreal • London • Munich • Paris • Madrid Capetown • Sydney • Tokyo • Singapore • Mexico City Sanders_book.indb 3 6/12/10 3:15:14 PM Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and the publisher was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed with initial capital letters or in all capitals. The authors and publisher have taken care in the preparation of this book, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. NVIDIA makes no warranty or representation that the techniques described herein are free from any Intellectual Property claims. The reader assumes all risk of any such claims based on his or her use of these techniques. The publisher offers excellent discounts on this book when ordered in quantity for bulk purchases or special sales, which may include electronic versions and/or custom covers and content particular to your business, training goals, marketing focus, and branding interests. For more information, please contact: U.S. Corporate and Government Sales (800) 382-3419 [email protected] For sales outside the United States, please contact: International Sales [email protected] Visit us on the Web: informit.com/aw Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sanders, Jason. -

Bitfusion Guide to CUDA Installation Bitfusion Guides Bitfusion: Bitfusion Guide to CUDA Installation

WHITE PAPER–OCTOBER 2019 Bitfusion Guide to CUDA Installation Bitfusion Guides Bitfusion: Bitfusion Guide to CUDA Installation Table of Contents Purpose 3 Introduction 3 Some Sources of Confusion 4 So Many Prerequisites 4 Installing the NVIDIA Repository 4 Installing the NVIDIA Driver 6 Installing NVIDIA CUDA 6 Installing cuDNN 7 Speed It Up! 8 Upgrading CUDA 9 WHITE PAPER | 2 Bitfusion: Bitfusion Guide to CUDA Installation Purpose Bitfusion FlexDirect provides a GPU virtualization solution. It allows you to use the GPUs, or even partial GPUs (e.g., half of a GPU, or a quarter, or one-third of a GPU), on different servers as if they were attached to your local machine, a machine on which you can now run a CUDA application even though it has no GPUs of its own. Since Bitfusion FlexDirect software and ML/AI (machine learning/artificial intelligence) applications require other CUDA libraries and drivers, this document describes how to install the prerequisite software for both Bitfusion FlexDirect and for various ML/AI applications. If you already have your CUDA drivers and libraries installed, you can skip ahead to the chapter on installing Bitfusion FlexDirect. This document gives instruction and examples for Ubuntu, Red Hat, and CentOS systems. Introduction Bitfusion’s software tool is called FlexDirect. FlexDirect easily installs with a single command, but installing the third-party prerequisite drivers and libraries, plus any application and its prerequisite software, can seem a Gordian Knot to users new to CUDA code and ML/AI applications. We will begin untangling the knot with a table of the components involved. -

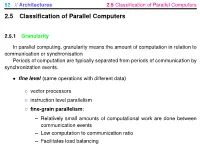

2.5 Classification of Parallel Computers

52 // Architectures 2.5 Classification of Parallel Computers 2.5 Classification of Parallel Computers 2.5.1 Granularity In parallel computing, granularity means the amount of computation in relation to communication or synchronisation Periods of computation are typically separated from periods of communication by synchronization events. • fine level (same operations with different data) ◦ vector processors ◦ instruction level parallelism ◦ fine-grain parallelism: – Relatively small amounts of computational work are done between communication events – Low computation to communication ratio – Facilitates load balancing 53 // Architectures 2.5 Classification of Parallel Computers – Implies high communication overhead and less opportunity for per- formance enhancement – If granularity is too fine it is possible that the overhead required for communications and synchronization between tasks takes longer than the computation. • operation level (different operations simultaneously) • problem level (independent subtasks) ◦ coarse-grain parallelism: – Relatively large amounts of computational work are done between communication/synchronization events – High computation to communication ratio – Implies more opportunity for performance increase – Harder to load balance efficiently 54 // Architectures 2.5 Classification of Parallel Computers 2.5.2 Hardware: Pipelining (was used in supercomputers, e.g. Cray-1) In N elements in pipeline and for 8 element L clock cycles =) for calculation it would take L + N cycles; without pipeline L ∗ N cycles Example of good code for pipelineing: §doi =1 ,k ¤ z ( i ) =x ( i ) +y ( i ) end do ¦ 55 // Architectures 2.5 Classification of Parallel Computers Vector processors, fast vector operations (operations on arrays). Previous example good also for vector processor (vector addition) , but, e.g. recursion – hard to optimise for vector processors Example: IntelMMX – simple vector processor. -

Parallel Architectures and Algorithms for Large-Scale Nonlinear Programming

Parallel Architectures and Algorithms for Large-Scale Nonlinear Programming Carl D. Laird Associate Professor, School of Chemical Engineering, Purdue University Faculty Fellow, Mary Kay O’Connor Process Safety Center Laird Research Group: http://allthingsoptimal.com Landscape of Scientific Computing 10$ 1$ 50%/year 20%/year Clock&Rate&(GHz)& 0.1$ 0.01$ 1980$ 1985$ 1990$ 1995$ 2000$ 2005$ 2010$ Year& [Steven Edwards, Columbia University] 2 Landscape of Scientific Computing Clock-rate, the source of past speed improvements have stagnated. Hardware manufacturers are shifting their focus to energy efficiency (mobile, large10" data centers) and parallel architectures. 12" 10" 1" 8" 6" #"of"Cores" Clock"Rate"(GHz)" 0.1" 4" 2" 0.01" 0" 1980" 1985" 1990" 1995" 2000" 2005" 2010" Year" 3 “… over a 15-year span… [problem] calculations improved by a factor of 43 million. [A] factor of roughly 1,000 was attributable to faster processor speeds, … [yet] a factor of 43,000 was due to improvements in the efficiency of software algorithms.” - attributed to Martin Grotschel [Steve Lohr, “Software Progress Beats Moore’s Law”, New York Times, March 7, 2011] Landscape of Computing 5 Landscape of Computing High-Performance Parallel Architectures Multi-core, Grid, HPC clusters, Specialized Architectures (GPU) 6 Landscape of Computing High-Performance Parallel Architectures Multi-core, Grid, HPC clusters, Specialized Architectures (GPU) 7 Landscape of Computing data VM iOS and Android device sales High-Performance have surpassed PC Parallel Architectures iPhone performance -

(GPU) Computing

Graphics Processing Unit (GPU) computing This section describes the graphics processing unit (GPU) computing feature of OptiSystem. Note: The GPU computing feature is only configurable with OptiSystem Version 11 (or higher) What is GPU computing? GPU computing or GPGPU takes advantage of a computer’s grahics processing card to augment the speed of general purpose scientific and engineering computing tasks. Compute Unified Device Architecture (CUDA) implementation for OptiSystem NVIDIA revolutionized the GPGPU and accelerated computing when it introduced a new parallel computing architecture: Compute Unified Device Architecture (CUDA). CUDA is both a hardware and software architecture for issuing and managing computations within the GPU, thus allowing it to operate as a generic data-parallel computing device. CUDA allows the programmer to take advantage of the parallel computing power of an NVIDIA graphics card to perform general purpose computations. OptiSystem CUDA implementation The OptiSystem model for GPU computing involves using a central processing unit (CPU) and GPU together in a heterogeneous co-processing computing model. The sequential part of the application runs on the CPU and the computationally-intensive part is accelerated by the GPU. In the OptiSystem GPU programming model, the application has been modified to map the compute-intensive kernels to the GPU. The remainder of the application remains within the CPU. CUDA parallel computing architecture The NVIDIA CUDA parallel computing architecture is enabled on GeForce®, Quadro®, and Tesla™ products. Whereas GeForce and Quadro are designed for consumer graphics and professional visualization respectively, the Tesla product family is designed ground-up for parallel computing and offers exclusive computing 3 GRAPHICS PROCESSING UNIT (GPU) COMPUTING features, and is the recommended choice for the OptiSystem GPU. -

Computer Hardware Architecture Lecture 4

Computer Hardware Architecture Lecture 4 Manfred Liebmann Technische Universit¨atM¨unchen Chair of Optimal Control Center for Mathematical Sciences, M17 [email protected] November 10, 2015 Manfred Liebmann November 10, 2015 Reading List • Pacheco - An Introduction to Parallel Programming (Chapter 1 - 2) { Introduction to computer hardware architecture from the parallel programming angle • Hennessy-Patterson - Computer Architecture - A Quantitative Approach { Reference book for computer hardware architecture All books are available on the Moodle platform! Computer Hardware Architecture 1 Manfred Liebmann November 10, 2015 UMA Architecture Figure 1: A uniform memory access (UMA) multicore system Access times to main memory is the same for all cores in the system! Computer Hardware Architecture 2 Manfred Liebmann November 10, 2015 NUMA Architecture Figure 2: A nonuniform memory access (UMA) multicore system Access times to main memory differs form core to core depending on the proximity of the main memory. This architecture is often used in dual and quad socket servers, due to improved memory bandwidth. Computer Hardware Architecture 3 Manfred Liebmann November 10, 2015 Cache Coherence Figure 3: A shared memory system with two cores and two caches What happens if the same data element z1 is manipulated in two different caches? The hardware enforces cache coherence, i.e. consistency between the caches. Expensive! Computer Hardware Architecture 4 Manfred Liebmann November 10, 2015 False Sharing The cache coherence protocol works on the granularity of a cache line. If two threads manipulate different element within a single cache line, the cache coherency protocol is activated to ensure consistency, even if every thread is only manipulating its own data. -

Massively Parallel Computing with CUDA

Massively Parallel Computing with CUDA Antonino Tumeo Politecnico di Milano 1 GPUs have evolved to the point where many real world applications are easily implemented on them and run significantly faster than on multi-core systems. Future computing architectures will be hybrid systems with parallel-core GPUs working in tandem with multi-core CPUs. Jack Dongarra Professor, University of Tennessee; Author of “Linpack” Why Use the GPU? • The GPU has evolved into a very flexible and powerful processor: • It’s programmable using high-level languages • It supports 32-bit and 64-bit floating point IEEE-754 precision • It offers lots of GFLOPS: • GPU in every PC and workstation What is behind such an Evolution? • The GPU is specialized for compute-intensive, highly parallel computation (exactly what graphics rendering is about) • So, more transistors can be devoted to data processing rather than data caching and flow control ALU ALU Control ALU ALU Cache DRAM DRAM CPU GPU • The fast-growing video game industry exerts strong economic pressure that forces constant innovation GPUs • Each NVIDIA GPU has 240 parallel cores NVIDIA GPU • Within each core 1.4 Billion Transistors • Floating point unit • Logic unit (add, sub, mul, madd) • Move, compare unit • Branch unit • Cores managed by thread manager • Thread manager can spawn and manage 12,000+ threads per core 1 Teraflop of processing power • Zero overhead thread switching Heterogeneous Computing Domains Graphics Massive Data GPU Parallelism (Parallel Computing) Instruction CPU Level (Sequential -

CUDA Flux: a Lightweight Instruction Profiler for CUDA Applications

CUDA Flux: A Lightweight Instruction Profiler for CUDA Applications Lorenz Braun Holger Froning¨ Institute of Computer Engineering Institute of Computer Engineering Heidelberg University Heidelberg University Heidelberg, Germany Heidelberg, Germany [email protected] [email protected] Abstract—GPUs are powerful, massively parallel processors, hardware, it lacks verbosity when it comes to analyzing the which require a vast amount of thread parallelism to keep their different types of instructions executed. This problem is aggra- thousands of execution units busy, and to tolerate latency when vated by the recently frequent introduction of new instructions, accessing its high-throughput memory system. Understanding the behavior of massively threaded GPU programs can be for instance floating point operations with reduced precision difficult, even though recent GPUs provide an abundance of or special function operations including Tensor Cores for ma- hardware performance counters, which collect statistics about chine learning. Similarly, information on the use of vectorized certain events. Profiling tools that assist the user in such analysis operations is often lost. Characterizing workloads on PTX for their GPUs, like NVIDIA’s nvprof and cupti, are state-of- level is desirable as PTX allows us to determine the exact types the-art. However, instrumentation based on reading hardware performance counters can be slow, in particular when the number of the instructions a kernel executes. On the contrary, nvprof of metrics is large. Furthermore, the results can be inaccurate as metrics are based on a lower-level representation called SASS. instructions are grouped to match the available set of hardware Still, even if there was an exact mapping, some information on counters. -

GPU: Power Vs Performance

IT 14 015 Examensarbete 30 hp June 2014 GPU: Power vs Performance Siddhartha Sankar Mondal Institutionen för informationsteknologi Department of Information Technology Abstract GPU: Power vs Performance Siddhartha Sankar Mondal Teknisk- naturvetenskaplig fakultet UTH-enheten GPUs are widely being used to meet the ever increasing demands of High performance computing. High-end GPUs are one of the highest consumers of power Besöksadress: in a computer. Power dissipation has always been a major concern area for computer Ångströmlaboratoriet Lägerhyddsvägen 1 architects. Due to power efficiency demands modern CPUs have moved towards Hus 4, Plan 0 multicore architectures. GPUs are already massively parallel architectures. There has been some encouraging results for power efficiency in CPUs by applying DVFS . The Postadress: vision is that a similar approach would also provide encouraging results for power Box 536 751 21 Uppsala efficiency in GPUs. Telefon: In this thesis we have analyzed the power and performance characteristics of GPU at 018 – 471 30 03 different frequencies. To help us achieve that, we have made a set of Telefax: microbenchmarks with different levels of memory boundedness and threads. We have 018 – 471 30 00 also used benchmarks from CUDA SDK and Parboil. We have used a GTX580 Fermi based GPU. We have also made a hardware infrastructure that accurately measures Hemsida: the power being consumed by the GPU. http://www.teknat.uu.se/student Handledare: Stefanos Kaxiras Ämnesgranskare: Stefanos Kaxiras Examinator: Ivan Christoff IT 14 015 Sponsor: UPMARC Tryckt av: Reprocentralen ITC Ahëuouu± I would like to thank my supervisor Prof. Stefanos Kaxiras for giving me the wonderful opportunity to work on this interesting topic. -

An Introduction to Gpus, CUDA and Opencl

An Introduction to GPUs, CUDA and OpenCL Bryan Catanzaro, NVIDIA Research Overview ¡ Heterogeneous parallel computing ¡ The CUDA and OpenCL programming models ¡ Writing efficient CUDA code ¡ Thrust: making CUDA C++ productive 2/54 Heterogeneous Parallel Computing Latency-Optimized Throughput- CPU Optimized GPU Fast Serial Scalable Parallel Processing Processing 3/54 Why do we need heterogeneity? ¡ Why not just use latency optimized processors? § Once you decide to go parallel, why not go all the way § And reap more benefits ¡ For many applications, throughput optimized processors are more efficient: faster and use less power § Advantages can be fairly significant 4/54 Why Heterogeneity? ¡ Different goals produce different designs § Throughput optimized: assume work load is highly parallel § Latency optimized: assume work load is mostly sequential ¡ To minimize latency eXperienced by 1 thread: § lots of big on-chip caches § sophisticated control ¡ To maXimize throughput of all threads: § multithreading can hide latency … so skip the big caches § simpler control, cost amortized over ALUs via SIMD 5/54 Latency vs. Throughput Specificaons Westmere-EP Fermi (Tesla C2050) 6 cores, 2 issue, 14 SMs, 2 issue, 16 Processing Elements 4 way SIMD way SIMD @3.46 GHz @1.15 GHz 6 cores, 2 threads, 4 14 SMs, 48 SIMD Resident Strands/ way SIMD: vectors, 32 way Westmere-EP (32nm) Threads (max) SIMD: 48 strands 21504 threads SP GFLOP/s 166 1030 Memory Bandwidth 32 GB/s 144 GB/s Register File ~6 kB 1.75 MB Local Store/L1 Cache 192 kB 896 kB L2 Cache 1.5 MB 0.75 MB -

Cuda C Programming Guide

CUDA C PROGRAMMING GUIDE PG-02829-001_v10.0 | October 2018 Design Guide CHANGES FROM VERSION 9.0 ‣ Documented restriction that operator-overloads cannot be __global__ functions in Operator Function. ‣ Removed guidance to break 8-byte shuffles into two 4-byte instructions. 8-byte shuffle variants are provided since CUDA 9.0. See Warp Shuffle Functions. ‣ Passing __restrict__ references to __global__ functions is now supported. Updated comment in __global__ functions and function templates. ‣ Documented CUDA_ENABLE_CRC_CHECK in CUDA Environment Variables. ‣ Warp matrix functions now support matrix products with m=32, n=8, k=16 and m=8, n=32, k=16 in addition to m=n=k=16. www.nvidia.com CUDA C Programming Guide PG-02829-001_v10.0 | ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1. Introduction.........................................................................................1 1.1. From Graphics Processing to General Purpose Parallel Computing............................... 1 1.2. CUDA®: A General-Purpose Parallel Computing Platform and Programming Model.............3 1.3. A Scalable Programming Model.........................................................................4 1.4. Document Structure...................................................................................... 5 Chapter 2. Programming Model............................................................................... 7 2.1. Kernels......................................................................................................7 2.2. Thread Hierarchy........................................................................................ -

CUDA 11 and A100 - WHAT’S NEW? Markus Hrywniak, 23Rd June 2020 TOPICS for TODAY

CUDA 11 AND A100 - WHAT’S NEW? Markus Hrywniak, 23rd June 2020 TOPICS FOR TODAY Ampere architecture – A100, powering DGX–A100, HGX-A100... and soon, FZ Jülich‘s JUWELS Booster New CUDA 11 Toolkit release Overview of features Talk next week: Third generation Tensor Cores GTC talks go into much more details. See references! 2 HGX-A100 4-GPU HGX-A100 8-GPU • 4 A100 with NVLINK • 8 A100 with NVSwitch 3 HIERARCHY OF SCALES Multi-System Rack Multi-GPU System Multi-SM GPU Multi-Core SM Unlimited Scale 8 GPUs 108 Multiprocessors 2048 threads 4 AMDAHL’S LAW serial section parallel section serial section Amdahl’s Law parallel section Shortest possible runtime is sum of serial section times Time saved serial section Some Parallelism Increased Parallelism Infinite Parallelism Program time = Parallel sections take less time Parallel sections take no time sum(serial times + parallel times) Serial sections take same time Serial sections take same time 5 OVERCOMING AMDAHL: ASYNCHRONY & LATENCY serial section parallel section serial section Split up serial & parallel components parallel section serial section Some Parallelism Task Parallelism Infinite Parallelism Program time = Parallel sections overlap with serial sections Parallel sections take no time sum(serial times + parallel times) Serial sections take same time 6 OVERCOMING AMDAHL: ASYNCHRONY & LATENCY CUDA Concurrency Mechanisms At Every Scope CUDA Kernel Threads, Warps, Blocks, Barriers Application CUDA Streams, CUDA Graphs Node Multi-Process Service, GPU-Direct System NCCL, CUDA-Aware MPI, NVSHMEM 7 OVERCOMING AMDAHL: ASYNCHRONY & LATENCY Execution Overheads Non-productive latencies (waste) Operation Latency Network latencies Memory read/write File I/O ..