Title Sounding Out: Performance Drawing in Response to the Outside

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To the Ends of the Earth: Art and Environment | Tate

Research Online research publications RESEARCH PAPER To the Ends of the Earth: Art and Environment Art & Environment By Nicholas Alfrey, Stephen Daniels, Joy Sleeman 11 May 2012 Introducing the group of articles devoted to the theme of ‘Art & Environment’ in issue 17 of Tate Papers, this essay reflects on changing perceptions of the term ‘environment’ in relation to artistic practices and describes the context for a series of case studies of sites, spaces and processes that extend from the immediate locality to the most remote boundaries of knowledge and experience. The group of articles devoted to the theme of art and environment in issue 17 of Tate Papers aims to explore new research frontiers between visual art and the material environment. The papers arise from a conference held at Tate Britain in June 2010 at which a range of practitioners and scholars – artists, writers, curators, theorists, historians and geographers – presented case studies of artworks addressing specific sites, spaces, places and landscapes in a variety of media, including film, photography, painting, sculpture and installation. The conference considered relations between artistic approaches to the environment and other forms of knowledge and practice, including scientific knowledge and social activism. The papers addressed cultural questions of weather and climate, ruin and waste, dwelling and movement, boundary and journey, and reflected on the way the environment is experienced and imagined and on the place of art in the material world. Held at a time when the emergent effects of economic crisis were intersecting with a more established sense of ecological crisis, the conference offered an opportunity to rethink the relations between art and environment, which had become central to a number of art exhibitions and publications. -

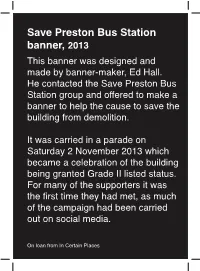

Save Preston Bus Station Banner

6DYH3UHVWRQ%XV6WDWLRQ EDQQHU 7KLVEDQQHUZDVGHVLJQHGDQG PDGHE\EDQQHUPDNHU(G+DOO +HFRQWDFWHGWKH6DYH3UHVWRQ%XV 6WDWLRQJURXSDQGRIIHUHGWRPDNHD EDQQHUWRKHOSWKHFDXVHWRVDYHWKH EXLOGLQJIURPGHPROLWLRQ ,WZDVFDUULHGLQDSDUDGHRQ 6DWXUGD\1RYHPEHUZKLFK EHFDPHDFHOHEUDWLRQRIWKHEXLOGLQJ EHLQJJUDQWHG*UDGH,,OLVWHGVWDWXV )RUPDQ\RIWKHVXSSRUWHUVLWZDV WKHÀUVWWLPHWKH\KDGPHWDVPXFK RIWKHFDPSDLJQKDGEHHQFDUULHG RXWRQVRFLDOPHGLD 2QORDQIURP,Q&HUWDLQ3ODFHV %XV6WDWLRQ&RQQHFWLRQV 7KHVHFDVHVFRQWDLQLWHPVEURXJKW LQE\SHRSOHZKRUHVSRQGHGWRD FDOORXWIRUREMHFWVWKDWFRQQHFWWKHP WR3UHVWRQ%XV6WDWLRQ 7KH\RIIHUDJOLPSVHLQWRZKDWWKH EXLOGLQJKDVPHDQWWRWKHSHRSOHRI 3UHVWRQDQGIXUWKHUDÀHOGRYHUWKH ODVW\HDUV 6DUDK:DONHU 7KLVSKRWRJUDSKZDVWDNHQE\ 6DUDKҋVGDXJKWHU(PPDLQ 6KHLVQRZVWXG\LQJDUFKLWHFWXUDO GHVLJQDW/LYHUSRRO8QLYHUVLW\ 1RUPDQ3D\QH 1RUPDQ3D\QHXVHGWKLV1DWLRQDO ([SUHVVGLVFRXQWFDUGLQWKHV ZKHQKHZDVDVWXGHQWDW8&/DQ DQGWUDYHOOHGIURP3UHVWRQ%XV 6WDWLRQWR6RXWKDPSWRQ +HOHQ/LQGVD\ 7KLVFROOHFWLRQRILWHPVUHÁHFWV +HOHQҋVORQJLQWHUHVWLQ3UHVWRQ%XV 6WDWLRQ7KHFRQFUHWHIUDJPHQWDQG &KULVWPDVFDUGZHUHIURP FROOHDJXHVDW/DQFDVKLUH3RVW6KH DOVRKDVDSDUWLQWKHÀOP &KDUOHV4XLFN 7KHSRVWFDUGZDVDSUHVHQW,WLV DOZD\VNHSWLQWKHEDFNRIKLV QRWHERRNDQGLVFDUULHGDWDOOWLPHV DVUHIHUHQFH 0U/HDYHU :DVDNHHQEXVVSRWWHU7KLV EXVVSRWWLQJPDQXDOGDWHVIURPWKH VDQGPDQ\RIWKHEXVHVLQLW XVHG3UHVWRQ%XV6WDWLRQ 5LWD:KLWORFN 7KLVPXJDQGFRDVWHUXVHGWREH VROGLQ3UHVWRQ7RXULVW,QIRUPDWLRQ &HQWUHZKHUH5LWDZDV0DQDJHU 6KHSXUFKDVHGWKHPDVVKHORYHV %UXWDOLVWDUFKLWHFWXUH &KULV/RQHUJDQ &KULVLVD6HQLRU(QJLQHHUDW$583 LQ0DQFKHVWHU$OORIWKHVWDIILQWKH RIÀFHKDYHDFXEHZLWKWKHLUSLFWXUH RQ,WDOVRLQFOXGHVVRPHWKLQJ -

OPEN LETTER in Support of CATHERINE De ZEGHER

OPEN LETTER in support of CATHERINE de ZEGHER About 7 months ago, we learned through the press that Catherine de Zegher had been temporarily suspended as Director of the Museum of Fine Arts of Ghent (MSK). It followed a 7 weeks media campaign of allegations made against the museum and its presentation within the permanent collection of the Russian avant-garde art from the Dieleghem Foundation, based in Brussels. The media allegations had risen to a crescendo, with the most extravagant claims being made, claims, which on examination appeared to have no factual basis and no discernible verifiable evidence. Malign motives were imputed to all those involved with the exhibition. In particular the personal attacks against Catherine de Zegher reached a peculiar and unprecedented intensity that resulted in a trial by media. Under pressure of the escalating and widespread attacks the city of Ghent caved in and temporarily suspended Catherine de Zegher. Today, October 9, 2018, most obviously Catherine de Zegher’s position as “temporally suspended museum director” has not been clarified, and no additional scientific research or independent material-technical expertise have been initiated by municipal, regional, or national government authorities in Belgium to settle the authenticity of the Russian avant-garde works exhibited at the MSK. As a consequence, the mendacious allegations against her are kept alive and the situation seems to be lingering without solution in sight. The scope of allegations and measures of isolation of a director and curator internationally recognized for her artistic vision, her championing of art by women and art from diverse cultures, her broad knowledge and expertise, her ceaseless curiosity, the relevance of her museum programming and the quality of her widely influential exhibitions and many books, stupefy us. -

Collaborative Relationshipsaid & Abet

news venice biennale, international relations features artists and curators talking: issues and outcomes, arts funding: canadian comparison, open studios, postgraduate focus debate believe in film JUNE 2011 collaborative relationships aid & abet £5.95/ 8.55 11 MAY–26 JUN 13 JUL–28 AUG 7 MAY– 26 JUN JVA at Jerwood Space, JVA at Jerwood Space, JVA on tour London London DLI Museum & Art Gallery, Durham An exhibition of new works by Selected artists Farah the inaugural Jerwood Painting Bandookwala, Emmanuel Final chance to see the 2010 Fellows; Clare Mitten, Cara Boos, Heike Brachlow exhibition selected by Charles Nahaul and Corinna Till. and Keith Harrison exhibit Darwent, Jenni Lomax and newly commissioned work. Emma Talbot. Curated by mentors; Paul Bonaventura, The 2011 selectors are durham.gov.uk/dli Stephen Farthing RA Emmanuel Cooper, Siobhan Twitter: #JDP2010 and Chantal Joffe. Davis and Jonathan Watkins. jerwoodvisualarts.org jerwoodvisualarts.org CALL FOR ENTRIES 2011 Twitter: #JPF2011 Twitter: #JMO2011 Deadline: Mon 20 June at 5pm The 2011 selectors are Iwona Blazwick, Tim Marlow and Rachel Whiteread. Apply online at jerwoodvisualarts.org Twitter: #JDP2011 Artist Associates: Beyond The Commission Saturday 16 July 2011, 10.30am – 4pm The Arts University College at Bournemouth | £30 / £20 concessions Artist Associates: Beyond the Commission focuses on the practice of supporting artists within the contemporary visual arts beyond the traditional curatorial, exhibition and commissioning role of the public sector, including this mentoring, advice, advocacy, and training. Confirmed Speakers: Simon Faithfull, (Artist and ArtSway Associate) Alistair Gentry (Artist and Writer, Market Project) Donna Lynas (Director, Wysing Arts Centre) Dida Tait (Head of Membership & Market Development, Contemporary Art Society) Chaired by Mark Segal (Director, ArtSway). -

Ne W Forest Pavilion 52Nd International Art Exhibition La Bi Ennale Di Venezia

NE W FOREST PAVILION 52ND INTERNATIONAL ART EXHIBITION LA BI ENNALE DI VENEZIA ESSAYS MARTIN COOMER on SIMON FAITHFULL ANNA-CATHARINA GEBBERS on BEATE GÜTSCHOW JOHN SLYCE on ANNE HARDY COLM LALLY & CECILIA WEE on IGLOO DAVID THORP on MELANIE MANCHOT CHARLOTTE FROST on STANZA New Forest Pavilion published by ArtSway and The Arts Institute at Bournemouth on the occasion of the exhibitions: NEW FOREST PAVILION 52nd International Art Exhibition - la Biennale di Venezia Palazzo Zenobio 10 June - 1 July 2007 and NEW FOREST PAVILION - LOCAL ArtSway 26 May - 15 July 2007 ArtSway, Station Road, Sway, Hampshire, SO41 6BA The Arts Institute at Bournemouth, Wallisdown, Poole, Dorset, BH12 5HH Editors: Peter Bonnell, Laura McLean-Ferris and Josepha Sanna English Translation from German: R. Jay Magill & Tanja Maka (text by Anna-Catharina Gebbers) All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted at any time or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the copyright holders. Set in Nilland and Soho. Printed by Printwise, Lymington, England © the artists and the authors ISBN: 0-9543930-9-0 [ArtSway] ISBN: 978-0-901196-20-0 [The Arts Institute at Bournemouth] Introduction New Forest Pavilion is an ArtSway international project that presents the work of six artists to a global audience within the framework of ArtSway’s innovative artist support scheme and residency programme. Five of the exhibiting artists are former ArtSway artists-in-residence, with Stanza being curated by SCAN (Southern Collaborative Arts Network). The overarching theme that unites all six within the context of New Forest Pavilion is their treatment of how one experiences transformation, modi!cation and change. -

Catherine De Zegher - the Inside Is the Outside: the Relational As the (Feminine) Space of the Radical

Catherine de Zegher - The Inside is the Outside: The Relational as the (Feminine) Space of the Radical Back to Issue 4 The Inside is the Outside: The Relational as the (Feminine) Space of the Radical by Catherine de Zegher © 2002 It may seem precursory to begin my essay with an image that has been haunting me since September 11, but in a concise way it prefigures many issues I will write about. It is an image of a work by the Chilean artist and poet, Cecilia Vicuna, who has been living in New York for many years. The work dates from 1981 and shows a word drawn in three colors of pigment (white, blue, and red—also the colors of the American flag) on the pavement of the West Side Highway with the World Trade Center on the horizon. It reads in Spanish: Parti si passion (Participation), which Vicuna unravels as “to say yes in passion, or to partake of suffering.” Revealing aspects of connectivity and compassion, the word spelled out on the road was as ephemeral as its meaning remained for the art world. Unnoticed and unacknowledged, it disappeared in dust, but becomes intelligible in the present. This precarious work tells us how certain art practices, in their continuous effort to press forward a different perception of the world, have a visionary content that is marginalized because of fixed conventional readings of art, but nevertheless is bound to be recognized. My essay will seek to uncover the latency of this kind of work in the second half of the twentieth century, which is slowly coming into being today and can be understood because of feminist practice, but also perhaps because of an abruptly changed reality. -

Mapping an Arm's Length

MAPPING AN ARM’S LENGTH: Body, Space and the Performativity of Drawing Roohi Shafiq Ahmed A thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts College of Fine Arts, University of New South Wales. 2013 ORIGINALITY STATEMENT ‘I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project's design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged.’ Signed …………………………………………….............. 28th March 2013 Date ……………………………………………................. ! DECLARATIONS Copyright Statement I hereby grant the University of New South Wales or its agents the right to archive and to make available my thesis or dissertation in whole or part in the University libraries in all forms of media, now or here after known, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I retain all proprietary rights, such as patent rights. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. -

All Our Relations: the 18Th Biennale of Sydney Connects Continents Mcmaster, Gerald

OCAD University Open Research Repository Faculty of Liberal Arts & Sciences 2012 All our relations: The 18th Biennale of Sydney connects continents McMaster, Gerald Suggested citation: McMaster, Gerald (2012) All our relations: The 18th Biennale of Sydney connects continents. Canadian Art, 29 (2). pp. 76-81. ISSN 0825-3854 Available at http://openresearch.ocadu.ca/id/eprint/2119/ Open Research is a publicly accessible, curated repository for the preservation and dissemination of scholarly and creative output of the OCAD University community. Material in Open Research is open access and made available via the consent of the author and/or rights holder on a non-exclusive basis. Since he took a leave of absence from the Art Gallery ofOntario (AGO) to work 011 the 18th Bie11nale of Syd11ey with atheri11e de Zegher, a former AGO colleag11e, Gerald McMa ter ha bee11 hard to pin dow11 for 11ews: he ha bee11 tral'elling the world a11rl looking at arti t for the show, which ope11s at the e11d ofJ1111e. We caught 11p with him via email a11d a ked a few q11e tion . Canadian Alt: What's your role in the 18th Biennale of Sydney? Gerald McMaster: Along with atherine de Zegher, I'm the arti tic director for the Biennale, which will open this June in Sydney, Au tralia. A collaborator , we began in conversation, with the idea that our dialogue would develop outward into other conver- sations. Essentially, we are a curatorial partner hip, omething that isn't new to me at all. Catherine and I had worked on an exhibition for the Drawing enter a Imo t ten year ago, and then we connected again for the rehang of the Canadian and European galleries at the Art Gallery of Ontario. -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE GOOD NATURE – a celebration of our planet, its beauty and its fragility and the essential part we all play in preserving it. 30 emerging and eminent artists were invited to make a new work in response to the theme. The work explores the themes of nature, our planet and the environment today. 16 September to 28 October 2017 Tuesday- Saturday 10am – 5pm CANDIDA STEVENS GALLERY Chichester West Sussex PO19 1BA Top left and clockwise: Alice Kettle, David Nash RA OBE, Michael Benson, Eileen Cooper RA OBE, Nicola Green GOOD NATURE celebrates the natural world through the observations of some of the leading artists working in the UK today who awaken our senses to the abundant beauty of our planet. They take inspiration from the warmth of the sun, the green lungs of the forests and the dark depths of the oceans, alongside all life that teems in and under them. We are reminded of the changing and fragile state of Earth and are invited to reflect on how it is necessary for all these elements to interconnect in order to exist. Highly acclaimed, environmental sculptor David Nash RA OBE shows a work created from a Holly tree, charred in his distinctive style, with an associated print. Eileen Cooper RA OBE, and this year’s curator of the RA Summer Show, includes a painting inspired by the domestic use of nature. Stephen Farthing RA makes a new print about the escapism PRESS RELEASE nature provides. Returning from highly successful exhibitions at Venice Biennale, Stephen Chambers RA takes a humorous look at manmade versus nature whilst Nicola Green makes a series of silkscreen prints in response to deforestation. -

Copyright Statement This Copy of The

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk 04 University of Plymouth Research Theses 01 Research Theses Main Collection 2020 Imagining and Remembering the Soldier at the Imperial War Museum (1980-1995) Buchanan, Jayne http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/15843 University of Plymouth All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. Copyright Statement This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and that no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without the author’s prior consent. This page is intentionally blank Imagining and Remembering the Soldier at the Imperial War Museum (1980-1995) by Jayne Buchanan A thesis submitted to the University of Plymouth in partial fulfilment for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Humanities & Performing Arts July 2019 Acknowledgements My thanks go to my supervisory team, Dr Jody Patterson and Dr Péter Bokody for their encouragement, insight and guidance through the past three years. Also to the Doctoral College at University of Plymouth and the wider staff in the Department of Humanities and the university for further valuable support and training. I am very grateful to Linda Kitson and John Keane for agreeing to be interviewed for this thesis and their openness to discuss their works and their time as war artists. -

The Currency of Art Ccw 862854 780955 Isbn 978-0-9558628-5-4 9 Isbn 978-0-9558628-5-4 E at Adu Ccw Gr School

BRIGHT 3 THE CURRENCY CURRENCY THE THE CURRENCY OF ART A COLLABORATION BETWEEN OF ART THE BARING ARCHIVE AND THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF CCW ISBNISBN 978-0-9558628-5-4 978-0-9558628-5-4 CCW GRADUATE SCHOOL CCW 9 780955 862854 3 3 THE CURRENCY OF ART The Currency of Art A COLLABORATION BETWEEN THE BARING ARCHIVE AND A collaboration between THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF CCW The Baring Archive and the Graduate School of CCW 5 5 CONTENTS Contents 7 The Currency of Art 10 Brief History of The Baring Archive 11 Selected Chronology of Barings Work The following order corresponds to the chronology of the items chosen from The Baring Archive. 12 1754: Devonshire Square What are Monuments for: to Celebrate, to Agitate or to Mourn? – Lubaina Himid 18 1766: The First Ledger Deleting the paper elegantly – Stephen Farthing 24 1804: Prospectus for the Louisiana Purchase The Americas Have Stolen my True Love Away – George Blacklock 30 1806: Study of Francis Baring by Thomas Lawrence Who? – Eileen Hogan 36 1810: Creamware Jug / 1884: Share Certificate Transfer – Geoff Quilley 40 1842: Road Between Santiago and Valparaíso … a fair calculation if not a certain operation. – Oriana Baddeley and Chris Wainwright 48 1859: Joshua Bates’ Diary / 1857–59: American Client Ledger Baring Antebellum – Bishopsgate Within CITY A.M. – Susan Johanknecht 54 1866: Letter from George White to Baring Brothers / Livorno from the Sea, Watercolour Folded and Sent – Rod Bugg 60 1908: Bearer Bond for City of Moscow 5% Issue X: 17 – Jane Collins and Peter Farley 66 1933: Argentinean Bearer Bond My Word is my Bond – Brian Webb 72 Biographies 6 6 7 7 THE CURRENCY OF ART The Currency of Art Eileen Hogan This publication arises from a collaborative project undertaken by The Baring Archive and the Graduate School of CCW (Camberwell College of Arts, Chelsea College of Art and Design and Wimbledon College of Art, three of the constituent colleges of University of the Arts London). -

Drawing from Turner

DRAWING FROM TURNER The full online catalogue available at: http://www.tate.org.uk/britain/exhibitions/drawingfromturner/default.shtm Drawing from a Turner original in the Prints and Drawings Room at Tate Britain Drawing From Turner is a collaborative project and exhibition jointly organised by Tate Britain and the University of the Arts London. The display includes the drawings of 30 contemporary artists displayed in conjunction with the original Turners from which they worked. Over the past two years some fifty participants have spent between three and thirty hours drawing directly from one of Turner’s drawings in the Prints and Drawings Room at Tate Britain. The thirty-five Turner drawings that became the subject of this project form a small but representative selection from the thousands of items in the Turner Bequest, the contents of the artist’s studio bequeathed to the nation on his death in 1851 and now housed in the Clore Gallery at Tate Britain. From the briefest pencil sketches to fully worked up landscape studies, these drawings provide a unique insight in the working methods and techniques of a great artist, almost as good as looking over his shoulder as he worked. The aim of this project was for the organisers to offer a receptive group of students and artists the opportunity to get to know and hopefully better understand the methods, inventions and creativity of a master draughtsman, Joseph Mallord William Turner. The goal was for them to simply draw from his drawings, not to make slavish copies or pointlessly extravagant interpretations. Throughout the project the word copy was avoided and instead participants were asked to think forensically about their chosen drawing by examining and not simply following in Turner’s footsteps.