Full Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Smithfield Review, Volume 20, 2016

In this issue — On 2 January 1869, Olin and Preston Institute officially became Preston and Olin Institute when Judge Robert M. Hudson of the 14th Circuit Court issued a charter Includes Ten Year Index for the school, designating the new name and giving it “collegiate powers.” — page 1 The On June 12, 1919, the VPI Board of Visitors unanimously elected Julian A. Burruss to succeed Joseph D. Eggleston as president of the Blacksburg, Virginia Smithfield Review institution. As Burruss began his tenure, veterans were returning from World War I, and America had begun to move toward a post-war world. Federal programs Studies in the history of the region west of the Blue Ridge for veterans gained wide support. The Nineteenth Amendment, giving women Volume 20, 2016 suffrage, gained ratification. — page 27 A Note from the Editors ........................................................................v According to Virginia Tech historian Duncan Lyle Kinnear, “he [Conrad] seemed Olin and Preston Institute and Preston and Olin Institute: The Early to have entered upon his task with great enthusiasm. Possessed as he was with a flair Years of Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University: Part II for writing and a ‘tongue for speaking,’ this ex-confederate secret agent brought Clara B. Cox ..................................................................................1 a new dimension of excitement to the school and to the town of Blacksburg.” — page 47 Change Amidst Tradition: The First Two Years of the Burruss Administration at VPI “The Indian Road as agreed to at Lancaster, June the 30th, 1744. The present Faith Skiles .......................................................................................27 Waggon Road from Cohongoronto above Sherrando River, through the Counties of Frederick and Augusta . -

SR V15 Cutler.Pdf (1.135Mb)

WHISKEY, SOLDIERS, AND VOTING: WESTERN VIRGINIA ELECTIONS IN THE 1790s Appendix A 1789 Montgomery County Congressional Poll List The following poll list for the 1789 congressional election in Montgomery County appears in Book 8 of Montgomery County Deeds and Wills, page 139. Original spellings, which are often erroneous, are preserved. The list has been reordered alphabetically. Alternative spellings from the tax records appear in parentheses. Other alternative spellings appear in brackets. Asterisks indicate individuals for whom no tax record was found. 113 Votes from February 2, 1789: Andrew Moore Voters Daniel Colins* Thomas Copenefer (Copenheefer) Duncan Gullion (Gullian) Henry Helvie (Helvey) James McGavock John McNilt* Francis Preston* 114 John Preston George Hancock Voters George Adams John Adams Thomas Alfred (Alford) Philip Arambester (Armbrister) Chales (Charles) Baker Daniel Bangrer* William Bartlet (Berlet) William Brabston Andrew Brown John Brown Robert Buckhanan William Calfee (Calfey) William Calfee Jr. (Calfey) James Campbell George Carter Robert Carter* Stophel Catring (Stophell Kettering) Thadeus (Thaddeas) Cooley Ruebin Cooley* Robert Cowden John Craig Andrew Crocket (Crockett) James Crockett Joseph Crocket (Crockett) Richard Christia! (Crystal) William Christal (Crystal) Michel Cutney* [Courtney; Cotney] James Davies Robert Davies (Davis) George Davis Jr. George Davis Sr. John Davis* Joseph Davison (Davidson) Francis Day John Draper Jr. Charles Dyer (Dier) Joseph Eaton George Ewing Jr. John Ewing Samuel Ewing Joseph -

William Preston and the Revolutionary Settlement

Journal of Backcountry Studies EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the third and last installment of the author’s 1990 University of Maryland dissertation, directed by Professor Emory Evans, to be republished in JBS. Dr. Osborn is President of Pacific Union College. William Preston and the Revolutionary Settlement BY RICHARD OSBORN Patriot (1775-1778) Revolutions ultimately conclude with a large scale resolution in the major political, social, and economic issues raised by the upheaval. During the final two years of the American Revolution, William Preston struggled to anticipate and participate in the emerging American regime. For Preston, the American Revolution involved two challenges--Indians and Loyalists. The outcome of his struggles with both groups would help determine the results of the Revolution in Virginia. If Preston could keep the various Indian tribes subdued with minimal help from the rest of Virginia, then more Virginians would be free to join the American armies fighting the English. But if he was unsuccessful, Virginia would have to divert resources and manpower away from the broader colonial effort to its own protection. The other challenge represented an internal one. A large number of Loyalist neighbors continually tested Preston's abilities to forge a unified government on the frontier which could, in turn, challenge the Indians effectivel y and the British, if they brought the war to Virginia. In these struggles, he even had to prove he was a Patriot. Preston clearly placed his allegiance with the revolutionary movement when he joined with other freeholders from Fincastle County on January 20, 1775 to organize their local county committee in response to requests by the Continental Congress that such committees be established. -

G:\Trimble Families, July 22, 1997.Wpd

Trimble Families a Partial Listing of the Descendants of Some Colonial Families Revised Eugene Earl Trimble July 22, 1997 1 PREFACE This Trimble record deals primarily with the ancestral line of the writer and covers the period from the time of arrival of James Trimble (or Turnbull; born ca. 1705; died 1767) in America which may have been prior to March 11, 1734, until in most instances about 1850. Some few lines are, however, brought up to the present. The main purpose of this account is to present the earliest generations. With the census records from 1850 on, enumerating each individual, it is much easier to trace ancestors and descendants. Any one who has researched a family during the l700's knows how limited the available data are and how exceeding difficult the task is. One inevitably reaches the point where the search becomes more conjecture than fact, but man is an inquisitive creature and the lure of the unknown is irresistible. No attempt has been made to give all possible references. For this Trimble line and other Trimble lines the reader is referred to the 62 page manuscript on the Trimble Family by James Augustus LeConte (born Adairsville, Ga., July 19, 1870; died Atlanta, Ga., July 18, 1941) whose papers are at the University of Georgia at Athens; the Trimble Family research located in the Manuscript Department of The University of Virginia, by Kelley Walker Trimble (born Feb. 21, 1884; died Route l, Staunton, Va., after Feb. 12, 1955); the Trimble and related research and writings of Mrs. Jerome A. -

The History of the College of William and Mary from Its Foundation, 1693

1693 - 1870 m 1m mmtm m m m&NBm iKMi Sam On,•'.;:'.. m '' IIP -.•. m : . UBS . mm W3m BBSshsR iillltwlll ass I HHH1 m '. • ml §88 BmHRSSranH M£$ Sara ,mm. mam %£kff EARL GREGG SWEM LIBRARY THE COLLEGE OF WILLIAM AND MARY IN VIRGINIA Presented By Dorothy Dickinson PIPPEN'S a BOOI^ a g OllD STORE, 5j S) 60S N. Eutaw St. a. BALT WORE. BOOES EOUOE' j ESCHANQED. 31 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from LYRASIS Members and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/historyofcollege1870coll 0\JI.LCkj£ THE HISTORY College of William and Mary From its Foundation, 1693, to 1870. BALTIMOKE: Printed by John Murphy & Co. Publishers, Booksellers, Printers and Stationers, 182 Baltimore Street. 1870. Oath of Visitor, I. A. B., do golemnly promise and swear, that I will truly and faith- fully execute the duties of my office, as a vistor of William and Mary College, according to the best of my skill and judgment, without favour, affection or partiality. So help me God. Oath of President or Professor. I, do swear, that I will well and truly execute the duties of my office of according to the best of my ability. So help me God. THE CHARTER OF THE College of William and Mary, In Virginia. WILLIAM AND MARY, by the grace of God, of England, Scot- land, France and Ireland, King and Queen, defenders of the faith, &c. To all to whom these our present letters shall come, greeting. Forasmuch as our well-beloved and faithful subjects, constituting the General Assembly of our Colony of Virginia, have had it in their minds, and have proposed -

VAS1805 William Campbell

Southern Campaigns American Revolution Pension Statements & Rosters Petition of Heir of William Campbell VAS1805 2 Transcribed by Will Graves 3/22/15 [Methodology: Spelling, punctuation and/or grammar have been corrected in some instances for ease of reading and to facilitate searches of the database. Where the meaning is not compromised by adhering to the spelling, punctuation or grammar, no change has been made. Corrections or additional notes have been inserted within brackets or footnotes. Blanks appearing in the transcripts reflect blanks in the original. A bracketed question mark indicates that the word or words preceding it represent(s) a guess by me. The word 'illegible' or 'indecipherable' appearing in brackets indicates that at the time I made the transcription, I was unable to decipher the word or phrase in question. Only materials pertinent to the military service of the veteran and to contemporary events have been transcribed. Affidavits that provide additional information on these events are included and genealogical information is abstracted, while standard, 'boilerplate' affidavits and attestations related solely to the application, and later nineteenth and twentieth century research requests for information have been omitted. I use speech recognition software to make all my transcriptions. Such software misinterprets my southern accent with unfortunate regularity and my poor proofreading skills fail to catch all misinterpretations. Also, dates or numbers which the software treats as numerals rather than words are not corrected: for example, the software transcribes "the eighth of June one thousand eighty six" as "the 8th of June 1786." Please call material errors or omissions to my attention.] [From Digital Library of Virginia ] from Washington County Legislative Papers To the Hon. -

Chapter Xxiii Alexander Ewing

CHAPTER XXIII ALEXANDER EWING (1676/7-1738) of “THE LEVELL” OCTORARO HUNDRED, Cecil County, Maryland On page 16 of this work “Alexander Ewing, son of Robert Ewing was baptised on 18 January 1679/80, Burt Congregation” and also, “Margaret Ewing baptised 26 March 1678, daughter of Robert Ewing of Burt Congregation.” It is said she married Josias Porter and they had a daughter, Rachel, baptised 15 July 1711 (but had been born in 1706). The I.G.I. records that “Rachel Porter married Nathaniel Ewing 2 March 1721 [1721/22] in the Parish of Templemore in Derry (Londonderry) Ireland.” We have no reason to dispute this. If it be so, then Rachel is a niece of the above Alexander Ewing called by some “cousin” to Nathaniel. First Nathaniel on American Shores. Rachel Porter “had a brother James Porter born 1699,” was also reported. And, an Alexander Ewing, (Sr) is shown paying tax in 1729 in East Nottingham twp. Chester Co., PA next to one Alexander Ewing, Jr. Not necessarily son and father as, in that day Jr. and Sr. were used also to designate a younger and older person by the same name. This has been verified numbers of times. The “Jr.” there has been traced, somewhat, in Chapter XV. “THE LEVELL” was surveyed 3 March 1687 for Casparus Herman/Harman described as being a 900 acre tract on the S. Side of the Canawango (sic) [Conowingo] Creek running into the Susquehanna River, beginning at a bounded Beech Tree on a hill near the Creek Side. Benjamin Allen purchased 900 acres from Hermann’s son in 1714. -

Slavery in Ante-Bellum Southern Industries

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editors: John H. Bracey, Jr. and August Meier SLAVERY IN ANTE-BELLUM SOUTHERN INDUSTRIES Series C: Selections from the Virginia Historical Society Part 1: Mining and Smelting Industries Editorial Adviser Charles B. Dew Associate Editor and Guide compiled by Martin Schipper A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Slavery in ante-bellum southern industries [microform]. (Black studies research sources.) Accompanied by printed reel guides, compiled by Martin P. Schipper. Contents: ser. A. Selections from the Duke University Library / editorial adviser, Charles B. Dew, associate editor, Randolph Boehm—ser. B. Selections from the Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill—ser. C. Selections from the Virginia Historical Society / editorial adviser, Charles B. Dew, associate editor, Martin P. Schipper. 1. Slave labor—Southern States—History—Sources. 2. Southern States—Industries—Histories—Sources. I. Dew, Charles B. II. Boehm, Randolph. III. Duke University. Library. IV. University Publications of America (Firm). V. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Library. Southern Historical Collection. VI. Virginia Historical Society. HD4865 306.3′62′0975 91-33943 ISBN 1-55655-547-4 (ser. C : microfilm) CIP Compilation © 1996 by University Publications -

The Border South and the Secession Crisis, 1859-1861 Michael Dudley Robinson Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2013 Fulcrum of the Union: The Border South and the Secession Crisis, 1859-1861 Michael Dudley Robinson Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Robinson, Michael Dudley, "Fulcrum of the Union: The Border South and the Secession Crisis, 1859-1861" (2013). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 894. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/894 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. FULCRUM OF THE UNION: THE BORDER SOUTH AND THE SECESSION CRISIS, 1859- 1861 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Michael Dudley Robinson B.S. North Carolina State University, 2001 M.A. University of North Carolina – Wilmington, 2007 May 2013 For Katherine ii Acknowledgements Throughout the long process of turning a few preliminary thoughts about the secession crisis and the Border South into a finished product, many people have provided assistance, encouragement, and inspiration. The staffs at several libraries and archives helped me to locate items and offered suggestions about collections that otherwise would have gone unnoticed. I would especially like to thank Lucas R. -

H. Doc. 108-222

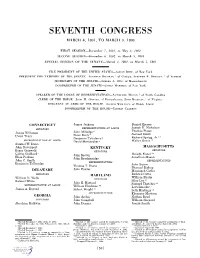

SEVENTH CONGRESS MARCH 4, 1801, TO MARCH 3, 1803 FIRST SESSION—December 7, 1801, to May 3, 1802 SECOND SESSION—December 6, 1802, to March 3, 1803 SPECIAL SESSION OF THE SENATE—March 4, 1801, to March 5, 1801 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—AARON BURR, of New York PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—ABRAHAM BALDWIN, 1 of Georgia; STEPHEN R. BRADLEY, 2 of Vermont SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—SAMUEL A. OTIS, of Massachusetts DOORKEEPER OF THE SENATE—JAMES MATHERS, of New York SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—NATHANIEL MACON, 3 of North Carolina CLERK OF THE HOUSE—JOHN H. OSWALD, of Pennsylvania; JOHN BECKLEY, 4 of Virginia SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—JOSEPH WHEATON, of Rhode Island DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—THOMAS CLAXTON CONNECTICUT James Jackson Daniel Hiester Joseph H. Nicholson SENATORS REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE Thomas Plater James Hillhouse John Milledge 6 Peter Early 7 Samuel Smith Uriah Tracy 12 Benjamin Taliaferro 8 Richard Sprigg, Jr. REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE 13 David Meriwether 9 Walter Bowie Samuel W. Dana John Davenport KENTUCKY MASSACHUSETTS SENATORS Roger Griswold SENATORS 5 14 Calvin Goddard John Brown Dwight Foster Elias Perkins John Breckinridge Jonathan Mason John C. Smith REPRESENTATIVES REPRESENTATIVES Benjamin Tallmadge John Bacon Thomas T. Davis Phanuel Bishop John Fowler DELAWARE Manasseh Cutler SENATORS MARYLAND Richard Cutts William Eustis William H. Wells SENATORS Samuel White Silas Lee 15 John E. Howard Samuel Thatcher 16 REPRESENTATIVE AT LARGE William Hindman 10 Levi Lincoln 17 James A. Bayard Robert Wright 11 Seth Hastings 18 REPRESENTATIVES Ebenezer Mattoon GEORGIA John Archer Nathan Read SENATORS John Campbell William Shepard Abraham Baldwin John Dennis Josiah Smith 1 Elected December 7, 1801; April 17, 1802. -

Washington City, 1800-1830 Cynthia Diane Earman Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School Fall 11-12-1992 Boardinghouses, Parties and the Creation of a Political Society: Washington City, 1800-1830 Cynthia Diane Earman Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Earman, Cynthia Diane, "Boardinghouses, Parties and the Creation of a Political Society: Washington City, 1800-1830" (1992). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 8222. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/8222 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOARDINGHOUSES, PARTIES AND THE CREATION OF A POLITICAL SOCIETY: WASHINGTON CITY, 1800-1830 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of History by Cynthia Diane Earman A.B., Goucher College, 1989 December 1992 MANUSCRIPT THESES Unpublished theses submitted for the Master's and Doctor's Degrees and deposited in the Louisiana State University Libraries are available for inspection. Use of any thesis is limited by the rights of the author. Bibliographical references may be noted, but passages may not be copied unless the author has given permission. Credit must be given in subsequent written or published work. A library which borrows this thesis for use by its clientele is expected to make sure that the borrower is aware of the above restrictions. -

JOHN JOHNS TRIGG, CONGRESSMAN by Ronald Paris

JOHN JOHNS TRIGG, CONGRESSMAN by Ronald Paris Beck Thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History APPROVED: Georfj'e Green -Shac.ke 1 fordP, Chairman Weldon A. Brown William E. M~ckie April, 1972 Blacksburg, Virginia ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Many persons contribute in varying degrees to the preparation of any historical work; this one was no exception. I am particularly indebted to Professor George Green Shackelford, who gave generously of his time, encouragement, and counsel, not only in the development of this study but also in the more demanding task of shaping a graduate student into a master of arts in history. I also wish to thank Professors Weldon A. Brown and William E. Mackie, who as members of my graduate committee and as second and third readers of this thesis gave me such good advice. Profound thanks must go to the archival and library staff of the following institutions, who have been kind and helpful in guiding me to research materials: the Carol M. Newman Library of Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, the Virginia Historical Society, the Viiginia State Library, the Tennessee State Library and Archives, and the clerk's office of the county of Bedford. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ii Chapters I. The Background and Early Life of John Johns Trigg . 1 II. In the Virginia House of Delegates, 1784-179 2 . 20 I I I. Trigg Plays "A Game Where Principles are the Stakes," In the House of Representatives, 1797-1800 ....