Use of Cloud-Based Graphic Narrative Software in Medical Ethics Teaching

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comic Strips and the American Family, 1930-1960 Dahnya Nicole Hernandez Pitzer College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Pitzer Senior Theses Pitzer Student Scholarship 2014 Funny Pages: Comic Strips and the American Family, 1930-1960 Dahnya Nicole Hernandez Pitzer College Recommended Citation Hernandez, Dahnya Nicole, "Funny Pages: Comic Strips and the American Family, 1930-1960" (2014). Pitzer Senior Theses. Paper 60. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/pitzer_theses/60 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pitzer Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pitzer Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FUNNY PAGES COMIC STRIPS AND THE AMERICAN FAMILY, 1930-1960 BY DAHNYA HERNANDEZ-ROACH SUBMITTED TO PITZER COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE BACHELOR OF ARTS DEGREE FIRST READER: PROFESSOR BILL ANTHES SECOND READER: PROFESSOR MATTHEW DELMONT APRIL 25, 2014 0 Table of Contents Acknowledgements...........................................................................................................................................2 Introduction.........................................................................................................................................................3 Chapter One: Blondie.....................................................................................................................................18 Chapter Two: Little Orphan Annie............................................................................................................35 -

Check All That Apply)

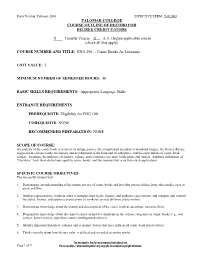

Form Version: February 2001 EFFECTIVE TERM: Fall 2003 PALOMAR COLLEGE COURSE OUTLINE OF RECORD FOR DEGREE CREDIT COURSE X Transfer Course X A.A. Degree applicable course (check all that apply) COURSE NUMBER AND TITLE: ENG 290 -- Comic Books As Literature UNIT VALUE: 3 MINIMUM NUMBER OF SEMESTER HOURS: 48 BASIC SKILLS REQUIREMENTS: Appropriate Language Skills ENTRANCE REQUIREMENTS PREREQUISITE: Eligibility for ENG 100 COREQUISITE: NONE RECOMMENDED PREPARATION: NONE SCOPE OF COURSE: An analysis of the comic book in terms of its unique poetics (the complicated interplay of word and image); the themes that are suggested in various works; the history and development of the form and its subgenres; and the expectations of comic book readers. Examines the influence of history, culture, and economics on comic book artists and writers. Explores definitions of “literature,” how these definitions apply to comic books, and the tensions that arise from such applications. SPECIFIC COURSE OBJECTIVES: The successful student will: 1. Demonstrate an understanding of the unique poetics of comic books and how that poetics differs from other media, such as prose and film. 2. Analyze representative works in order to interpret their styles, themes, and audience expectations, and compare and contrast the styles, themes, and audience expectations of works by several different artists/writers. 3. Demonstrate knowledge about the history and development of the comic book as an artistic, narrative form. 4. Demonstrate knowledge about the characteristics of and developments in the various subgenres of comic books (e.g., war comics, horror comics, superhero comics, underground comics). 5. Identify important historical, cultural, and economic factors that have influenced comic book artists/writers. -

American Comic Strips in Italy Going Through the Issues of Linus Published in 1967 and 1968: the Selected Cartoonists (E.G

MONOGRÁFICO Estudios de Traducción ISSN: 2174-047X https://dx.doi.org/10.5209/estr.71489 American Comics and Italian Cultural Identity in 1968: Translation Challenges in a Syncretic Text Laura Chiara Spinelli1 Recibido: 11 de septiembre de 2020 / Aceptado: 27 de octubre de 2020 Abstract. Translation supports the construction of a national identity through the selection of foreign texts to be transferred to the target language. Within this framework, the effort made in the 1960s by Italian editors and translators in giving new dignity to comics proves emblematic. This paper aims to reconstruct the reception of American comic strips in Italy going through the issues of Linus published in 1967 and 1968: the selected cartoonists (e.g. Al Capp, Jules Feiffer, and Walt Kelly) participate in the cultural debate of the time discussing politics, war, and civil rights. The analysis of the translation strategies adopted will reveal the difficulty of reproducing the polysemy of metaphors, idioms and puns, trying to maintain consistency between the visual and the verbal code, but primarily the need to create a purely Italian cultural discourse. Keywords: comics; translation; culture; visual code. [es] Cómics americanos e identidad cultural italiana en 1968: dificultades de traducción en un texto sincrético Resumen. La traducción contribuye a crear la identidad cultural de un país, con la decisión de traducir o no un texto extranjero a la lengua meta. En este contexto es remarcable el intento de los editores y traductores italianos de los años sesenta de dar una nueva dignidad al cómic. Este artículo tiene como objetivo reconstruir la recepción de las tiras cómicas de prensa americanas en Italia, con particular atención a los años 1967 y 1968 de la revista Linus: los autores (Al Capp, Jules Feiffer, Walt Kelly) participaron en el debate cultural de la época discutiendo sobre política, guerra, y de derechos civiles. -

Humor and Controversy in Peanuts Social Commentary New Exhibition at the Schulz Museum May 3 – November 2, 2014

Gina Huntsinger Marketing Director Charles M. Schulz Museum & Research Center (707) 579 4452 ext. 268 [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: April 22, 2014 “I feel that Peanuts reflects certain attitudes of life in our country today and perhaps some basic fears.” – Charles M. Schulz Detail © 1972 Peanuts Worldwide LLC Detail © 1963 Peanuts Worldwide LLC Humor and Controversy in Peanuts Social Commentary New Exhibition at the Schulz Museum May 3 – November 2, 2014 (Santa Rosa, CA) Health care, gun control, the environment, and racial equality were all topics broached by Charles M. Schulz in the fifty years he created the Peanuts comic strip. His beloved Peanuts characters raised issues of the day; Lucy embraced feminist philosophies, Linus panicked when he mistook snow for nuclear fallout, and Sally whispered about praying in school. Schulz also introduced Franklin, a black Peanuts character, into the predominately white cast July 31, 1968, just months after Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee. The Charles M. Schulz Museum and Research Center’s Social Commentary exhibition, which runs May 3 through November 2, 2014, re-examines Peanuts in the context of the social and political climate of the latter half of the twentieth century. In addition to original Peanuts comic strips, the exhibition features original Wee Pals, Gordo, Pogo, and Little Orphan Annie strips. It also highlights reaction letters from the Museum’s archives, and contextual artifacts. Schulz gently communicated the issues of the changing world around him through the unique pathos of his characters and his quick wit. And by remaining universally centrist, he gave readers the opportunity to interpret his comic strips according to their own personal dictates. -

Tom Spurgeon and Michael Dean. We Told You So: Comics As Art. Seattle: Fantagraphics Books, 2016

Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature Volume 42 Issue 1 A Planetary Republic of Comic Book Letters: Drawing Expansive Narrative Article 20 Boundaries 9-20-2017 Tom Spurgeon and Michael Dean. We Told You So: Comics As Art. Seattle: Fantagraphics Books, 2016. Rachel R. Miller The Ohio State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl Part of the Oral History Commons, and the Visual Studies Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Miller, Rachel R. (2017) "Tom Spurgeon and Michael Dean. We Told You So: Comics As Art. Seattle: Fantagraphics Books, 2016.," Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature: Vol. 42: Iss. 1, Article 20. https://doi.org/10.4148/2334-4415.1969 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tom Spurgeon and Michael Dean. We Told You So: Comics As Art. Seattle: Fantagraphics Books, 2016. Abstract Review of Tom Spurgeon and Michael Dean. We Told You So: Comics As Art. Seattle: Fantagraphics Books, 2016. Keywords Comics studies, history; alternative comics; journalism This book review is available in Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl/vol42/ iss1/20 Miller: Review of We Told You So: Comics As Art Tom Spurgeon and Michael Dean. We Told You So: Comics As Art. -

Guide to the Mahan Collection of American Humor and Cartoon Art, 1838-2017

Guide to the Mahan collection of American humor and cartoon art, 1838-2017 Descriptive Summary Title : Mahan collection of American humor and cartoon art Creator: Mahan, Charles S. (1938 -) Dates : 1838-2005 ID Number : M49 Size: 72 Boxes Language(s): English Repository: Special Collections University of South Florida Libraries 4202 East Fowler Ave., LIB122 Tampa, Florida 33620 Phone: 813-974-2731 - Fax: 813-396-9006 Contact Special Collections Administrative Summary Provenance: Mahan, Charles S., 1938 - Acquisition Information: Donation. Access Conditions: None. The contents of this collection may be subject to copyright. Visit the United States Copyright Office's website at http://www.copyright.gov/for more information. Preferred Citation: Mahan Collection of American Humor and Cartoon Art, Special Collections Department, Tampa Library, University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida. Biographical Note Charles S. Mahan, M.D., is Professor Emeritus, College of Public Health and the Lawton and Rhea Chiles Center for Healthy Mothers and Babies. Mahan received his MD from Northwestern University and worked for the University of Florida and the North Central Florida Maternal and Infant Care Program before joining the University of South Florida as Dean of the College of Public Health (1995-2002). University of South Florida Tampa Library. (2006). Special collections establishes the Dr. Charles Mahan Collection of American Humor and Cartoon Art. University of South Florida Library Links, 10(3), 2-3. Scope Note In addition to Disney animation catalogs, illustrations, lithographs, cels, posters, calendars, newspapers, LPs and sheet music, the Mahan Collection of American Humor and Cartoon Art includes numerous non-Disney and political illustrations that depict American humor and cartoon art. -

"The Cheapening of the Comics" by Bill Watterson

The Cheapening of the Comics Bill Watterson A speech delivered at the Festival of Cartoon Art, Ohio State University October 27, 1989 I received a letter from a 10-year-old this morning. He wrote, "Dear Mr. Watterson, I have been reading Calvin and Hobbes for a long time, and I'd like to know a few things. First, do you like the drawing of Calvin and Hobbes I did at the bottom of the page? Are you married, and do you have any kids? Have you ever been convicted of a felony?" What interested me about this last question was that he didn't ask if I'd been apprehended or arrested, but if I'd been convicted. Maybe a lot of cartoonists get off on technicalities, I don't know. It also interests me that he naturally assumed I wasn't trifling with misdemeanors, but had gone straight to aggravated assaults and car thefts. Seeing the high regard in which cartoonists are held today, it may surprise you to know that I've always wanted to draw a comic strip. My dad had a couple of Peanuts books that were among the first things I remember reading. One book was called "Snoopy," and it had a blank title page. The next page had a picture of Snoopy. I apparently figured the publisher had supplied the blank title page as a courtesy so the reader could use it to trace the drawing of Snoopy underneath. I added my own frontispiece to my dad's book. and afterward my dad must not have wanted the book back because I still have it. -

The Four-Panel Daily Comic Strip Must Be Judged by Different Standards

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 024 682 TE 000 912 By- Suhor. Charles Comics As Classics? Pub Date May 67 Note- Sp. Journal Cit- The Teachers Guide to Media & Methods: v3 n9 p26-9 May1967 EDRS Price MF- S0.25 HC-S0.35 Descriptors- *Cartoons. ContentAnalysis.CriticalReading. English Instruction. Graphic Arts, Literary Analysis. *Literary Conventions. Literary Discrimination, *Literary Genres.Literature Appreciation. *Mass Media. Satire, Symbols (Literary) Comicsas a special literary genre--must be judged by special criteria.In fact, the four-panel daily comic strip must be judged by differentstandards from the full-length comic book or the single- or double-frame comic.Among the four-panel strips are found comics that make a claim toliterary quality--"Lil Abner," "Pogo," and "Peanuts." These comic strips are "uniquely expressive" andtranscend the severe limitations of their genre through a creative use of languageand symbolism. Charles Schultz's technique in "Peanuts" involves understatement andsymbolism through which adult personality types act inthe guise of children. Walt Kelly's "Pogo-lingo"--a purposeful. comic distortion of language employing manypuns--becomes part of the cartooning style and. thus, has graphic value.Like Kelly, Al Capp is a satirist, and his Abner is in the American tradition of the innocent picarowhose responses reveal the shams of society. WS) a....1*1.1.11,t.woar...., a THE TEACHERSmedia GUIDE TO &methods An Expansion of SCHOOL PAPERBACK JOURNAL ISORY BOARD May, 1967 Val. 3, No, 9 arry K, Beyer EDITORIAL s't Prof. of Education Ohio State University SMILESTONE 3 ax Bogart st. Dir., Div. of Curriculum & Instruc. TEACHING AND THEORY te Dept. -

Ebook Download Peanuts Every Sunday: the 1960S Gift Box

PEANUTS EVERY SUNDAY: THE 1960S GIFT BOX SET PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Charles M Schulz | 576 pages | 22 Nov 2016 | Fantagraphics | 9781606999691 | English | Seattle, United States Peanuts Every Sunday: The 1960s Gift Box Set PDF Book View all copies of this ISBN edition:. Enabling JavaScript in your browser will allow you to experience all the features of our site. Schulz SET 1. These two volumes showcase Schulz at the absolute height of his creative powers with countless brilliant and near-legendary strips in these pages. It's an Adventure What a Nightmare Launching into the Look for similar items by category:. Schulz was born November 25, , in Minneapolis. Also available is our s gift box set of every 's Peanuts Sunday in one set! Two, in fact: The obnoxious Frieda of naturally curly hair fame, and her inert, seemingly boneless cat Faron. Our second paperback volume of the acclaimed Complete Peanuts series finds Schulz continuing to establish his tender and comic universe. The Complete Peanuts Tweet Tweet on Twitter. New York Times , March 6, The first two years of the best-selling comic strip, starring Snoopy and the gang, now in softcover. Historical Prices Loading Report an issue Please describe the issue If you have noticed an incorrect price, image or just something you'd like to tell us, enter it below. It's the Easter Beagle This specific ISBN edition is currently not available. Learn more about this copy. Add to Wishlist. Book Description Fantagraphics Books, From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Peanuts Every Sunday: has been scrupulously re-colored to match the original syndicate coloring - allowing readers once again to plunge back into Charles Schulz's marvelous world. -

Pogo Collection the Pogo Collection Is Differentiated from the Walt Kelly

Pogo Collection The Pogo Collection is differentiated from the Walt Kelly Collection because of differences in provenance. The following codes indicate the sources of materials in the Pogo Collection: * Part of the Milton Caniff Collection + Gift of Gus and Joanne Turbeville ^ Part of the Bill Crawford Collection # Purchased from Selby Kelly The Pogo Collection is in two series: Artwork and Papers. Series One: Artwork Original daily Pogo comic strips.Ink on paper. Size varies. AC I5 75 10/15/48# AC I5 76 05/13/53# AC I5 77 03/27/54# AC I5 78 10/02/54# AC I5 79 11/11/54# AC I5 1 03/14/58+ AC I5 80 05/28/58# AC I5 74 09/30/58^ AC I5 2 12/05/58+ AC I5 3 03/19/59+ AC I5 4 06/12/59+ AC I5 5 07/24/59+ AC I5 6 12/04/59+ AC I5 7 02/10/60+ AC I5 8 09/30/60+ AC I5 81 09/16/66# AC I5 9 01/10/67* AC I5 10 02/05/68+ AC I5 82 03/22/68# AC I5 83 04/02/68# AC I5 11 04/11/68+ AC I5 12 07/05/68+ AC I5 13 10/19/68+ AC I5 84 04/18/69# AC I5 14 07/10/69+ AC I5 15 10/03/69+ AC I5 85 03/28/70# AC I5 16 05/08/70+ AC I5 86 07/13/70# AC I5 17 10/03/70+ AC I5 18 10/23/70+ AC I5 19 10/30/70+ AC I5 20 11/19/70+ AC I5 21 12/12/70+ AC I5 22 02/13/71+ 2 AC I5 23 03/15/71+ AC I5 87 04/03/71# AC I5 88 04/21/71# AC I5 24 04/30/71+ AC I5 25 05/12/71+ AC I5 26 05/29/71+ AC I5 27 10/01/71+ AC I5 28 10/21/71+ AC I5 89 11/20/73# Original Sunday Pogo comic strips. -

The Comics Go to War

Kerry Soper The Comics Go to War On April 19, 2004, Garry Trudeau infused the typically bland fare of the daily comics page with some gritty realism: in that day’s installment of Doonesbury, a long-running character in the strip—B.D.—receives a serious wound to the leg while deployed in Iraq (figure 1). Echoing the trauma and disorientation of combat, he is depicted falling in and out of consciousness, and it is only after several daily episodes that the gravity of his wound becomes clear. In subsequent installments, B.D.’s harrowing experience continues; he goes from lying on the battlefield with one leg shattered, to being reunited with his family, and then engaging in a long rehabilitation process that includes wrestling with the effects of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (figure 2). Because Trudeau treated this episode with such nuance and unflinching honesty, many readers of the strip reported feeling a great deal of vicarious psychological empathy and trauma; for example, fans wrote into the Doonesbury website, saying that they were “breathless,” “crying,” and feeling “like it happened to a friend” (Montgomery). Figure 1: “Hey!” DOONESBURY © (19 April 2004) G. B. Trudeau. Reprinted with permission of UNIVERSAL UCLICK. All rights reserved. Figure 2: “Come on, Dad!” DOONESBURY © (20 December 2004) G. B. Trudeau. Reprinted with permission of UNIVERSAL UCLICK. All rights reserved. A majority of cultural critics cited the work for its originality and boldness in exploring the various facets of a wounded soldier’s experience with humor and nuance; and groups for injured vets added their praise, with one spokesperson saying that the strip gave “millions of Americans . -

Drawing Cartoons & Comics for Dummies

Drawing Cartoons & Comics FOR DUMmIES‰ by Brian Fairrington Drawing Cartoons & Comics For Dummies® Published by Wiley Publishing, Inc. 111 River St. Hoboken, NJ 07030-5774 www.wiley.com Copyright © 2009 by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Indianapolis, Indiana Published by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Indianapolis, Indiana Published simultaneously in Canada No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except as permit- ted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http:// www.wiley.com/go/permissions. Trademarks: Wiley, the Wiley Publishing logo, For Dummies, the Dummies Man logo, A Reference for the Rest of Us!, The Dummies Way, Dummies Daily, The Fun and Easy Way, Dummies.com, Making Everything Easier, and related trade dress are trademarks or registered trademarks of John Wiley & Sons, Inc. and/ or its affi liates in the United States and other countries, and may not be used without written permission. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. Wiley Publishing, Inc., is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.