Quick Reference Guide to Music Notation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TIME SIGNATURES, TEMPO, BEAT and GORDONIAN SYLLABLES EXPLAINED

TIME SIGNATURES, TEMPO, BEAT and GORDONIAN SYLLABLES EXPLAINED TIME SIGNATURES Time Signatures are represented by a fraction. The top number tells the performer how many beats in each measure. This number can be any number from 1 to infinity. However, time signatures, for us, will rarely have a top number larger than 7. The bottom number can only be the numbers 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, 512, et c. These numbers represent the note values of a whole note, half note, quarter note, eighth note, sixteenth note, thirty- second note, sixty-fourth note, one hundred twenty-eighth note, two hundred fifty-sixth note, five hundred twelfth note, et c. However, time signatures, for us, will only have a bottom numbers 2, 4, 8, 16, and possibly 32. Examples of Time Signatures: TEMPO Tempo is the speed at which the beats happen. The tempo can remain steady from the first beat to the last beat of a piece of music or it can speed up or slow down within a section, a phrase, or a measure of music. Performers need to watch the conductor for any changes in the tempo. Tempo is the Italian word for “time.” Below are terms that refer to the tempo and metronome settings for each term. BPM is short for Beats Per Minute. This number is what one would set the metronome. Please note that these numbers are generalities and should never be considered as strict ranges. Time Signatures, music genres, instrumentations, and a host of other considerations may make a tempo of Grave a little faster or slower than as listed below. -

Level 1 Theory Book (1.65

Table of Contents Lesson Page Material 1.1 1 Introduction to Music Letter Names The Octave 1.2 7 The Staff The Treble Clef Treble Clef Note Names Treble Clef Ledger Lines 1.3 17 The Bass Clef Bass Clef Note Names Bass Clef Ledger Lines Middle C 1.4 25 Dynamics Tempo Produced by The Salvation Army Music and Gospel Arts Department 3rd Edition Copyright 2018 The Salvation Army Canada and Bermuda Territory 2 Overlea Blvd., Toronto ON M4H 1P4 Original Author: Jeremy Smith Contributors: Leah Antle, Mark Barter, Susan Lee, Mike McCourt, Heather Osmond Lesson 1.1 - Introduction to Music We all hear lots of sounds at any given moment. Listen to the various sounds going on around you right now! How would you describe them? Do they have a pattern? Are they organized? Do you think this is music? Music is organized sound. We can use music to tell other people about Jesus Christ. This can be done through the use of singing, brass, percussion, piano and guitar music —any instrument that will promote God’s glory! Letter Names There are seven letters of the music alphabet: A B C D E F G We use these as note names to classify what a note or pitch sounds like. Notes can ascend (go higher): Notes can descend (go lower): 1 Level 1 Only seven letters? There can’t be just seven sounds in the whole world! The letter names of notes can be repeated when you run out! EXERCISE Fill in the missing note names! E A D B E D G B E D G F B 2 Level 1 The Octave When we have moved from one A to another A, we have played an octave, a term used in music to describe the space between notes of the same letter name. -

Pnrpartnc to Pmy

PurnNC Youn EmcrruC Bnss TocETHER machine heads (tuning pegs) STIP 1 Open your case right side up. SITP 2 Connect the strap securely to the strap buttons. fingerboard SIEP 3 Adjust the strap so that the body of the bass rests at or above your waist. STEP 4 Plug the audio cable into your bass, and then plug the cable into your amplifier. STEP 5 Turn the amplifier on and adjust the volume. toneAolume controls output jack strap button PnrPARtNc To Pmy STEP 1 Sit or stand up straighg with your shoul- ders relaxed. STEP 2 When standing the strap should sup port the full weight of the bass. When sitting restthe curve of the bass on your right thigh, and the back of the bass against your body. STEP 3 Bend your right elbow and position your forearm and wrist over the front of the bass. Your hand should be positioned toward the ground, with your fingers curved toward the strings. PnnpnRrNC To PLqy STEP 4 Fi.rce yon.:i ieft hand thumb behinci the neck. Your thumb shouid not curlover the top of the neckonto thefingerboard. STEP 5 Bend vour left wrist to position your fingers over the fingerboard. Arch your tingers, keeping your palm clear of the neck. Your thumb and fingers should f'cim a "C" shape. r*t \".'l\ l/- t/,*i-r,.i '!--;i ,--''.I;i\jt*-! ,\ 5ir-riRIC *nsg sTtLl ?i.i<*e r.'i;,..ri" ri3ht hanci midr,vay benveen the bridge anC the end of the fingerboard. TTfig.? ,<esi i,c'-;; r!sht hanri tiiumb on the .iih string {! sti'ing}. -

SMT Sweelinck Paper Text SHORT V2

SMT Graduate Workshop Peter Schubert: Renaissance Instrumental Music November 7, 2014 Derek Reme! Musical Architecture in Three Domains: Stretto, Suspension, and Diminution in Sweelinck's Chromatic Fantasia Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck's Chromatic Fantasia is among the most famous keyboard works of the sixteenth century.1 It served as a model for instrumental polyphony that was imitated throughout Europe in the seventeenth century.2 The fantasia's subject is treated in augmentation and diminution in four rhythmic levels and also in four-voice stretto. The initial stretto passage, which is repeated in diminution in the final climax of the piece, contains an unusual accented dissonance; in this style, accented dissonance is reserved only for suspensions. There are three metrical levels of suspensions used throughout the piece, which parallel the four rhythmic levels of the subject's augmentation and diminution – only a whole note suspension is missing. I propose that the unusual accented dissonance in the first four-voice stretto passage is actually a rearticulated whole note suspension, representing the missing fourth metrical level in that domain. Therefore, this stretto passage combines two domains at their fourth and most heightened level: stretto in four voices and suspension at the whole note. This passage also represents a structural "pillar," which, through its repetition, divides the piece into three large sections. In addition, the middle section contains two analogous "internal pillars," which further subdivide the middle into three subsections. The last large-scale section, the climax, introduces subject stretto at the eighth note level, or !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! 1 Harold Vogel, "Sweelinck's 'Orfeo' Die 'Fantasia Crommatica,'" Musik in die Kirche, No. -

Notes, Rhythm, and Meter Notes

Dr. Barbara Murphy University of Tennessee School of Music NOTES, RHYTHM, AND METER NOTES: Notes represent a duration or length of a sound. Notes consist of the head the stem and the flag or beam. note = head + stem + flag NOTE HEADS: The head of the note should be written as an oval (not a round circle) and should be centered on the line or space of the staff that represents the note. STEMS: Stems are notated on the right side of the note head and are ascending if the note head is on the 3rd line of the staff or below that line. Stems are notated on the left side of the note head and are descending if the note is on the 3rd line of the staff or above that line. Stems should be about 1 octave in length and should be straight up and down (not slanted). FLAGS: Flags are notated to the right of the stem whether the stem is on the right or left side of the note head. BEAMS: Notes should be beamed together to show the beat. Beams should therefore not cross beats. Beams should be straight lines, not curves. Beams may be slanted ascending or descending according to the contour of the notes. Beaming notes together may result in shortened or elongated stems on some notes. If beaming eighth notes and sixteenth notes together, sixteenth note beams should always go inside the beginning and ending stems. DURATIONS: Notes can have various durations and various names: American British (older version) double-whole breve whole semi-breve half minim quarter crotchet eighth quaver sixteenth semi-quaver thirty-second demi-semi-quaver sixty-fourth hemi-demi-semi-quaver These notes look like the following: double whole half quarter 8th 16th 32nd 64th whole In the above list, each note duration is one-half the duration of the preceding note duration. -

Musical Staff: the Skeleton Upon Which Musical Notation Is Hung

DulcimerCrossing.com General Music Theory Lesson 7 Steve Eulberg Musical Staff [email protected] Musical Staff: The skeleton upon which musical notation is hung. The Musical Staff is comprised of a clef (5 lines and 4 spaces) on which notes or rests are placed. At one time the staff was made up of 11 lines and 10 spaces. It proved very difficult to read many notes quickly and modern brain research has demonstrated that human perception actually does much better at quick recall when it can “chunk” information into groups smaller than 7. Many years ago, the people developing musical notation created a helpful modification by removing the line that designated where “Middle C” goes on the staff and ending up with two clefs that straddle middle C. The treble clef includes C and all the notes above it. The Bass clef includes C and all the notes below it. (See Transitional Musical Staff): DulcimerCrossing.com General Music Theory Lesson 7 Steve Eulberg Musical Staff [email protected] Now the current musical staff has separated the top staff and the bottom staff further apart, but they represent the same pattern of notes as above, now with room for lyrics between the staves. (Staves is the plural form of Staff) DulcimerCrossing.com General Music Theory Lesson 7 Steve Eulberg Musical Staff [email protected] The Staves are distinct from each other by their “Clef Sign.” (See above) This example shows the two most commonly used Clef Signs. Compare the Space and Line names in the Historical example and this one. The information is now “chunked” into less than 7 bits of information (which turns out to be the natural limit in the human brain!) on each staff. -

Introduction to Braille Music Transcription

Introduction to Braille Music Transcription Mary Turner De Garmo Second Edition Revised and edited by Lawrence R. Smith Music Braille Transcriber Bettye Krolick Music Braille Consultant Beverly McKenney Music Braille Transcriber Sandra Kelly Music Braille Advisor Volume I National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped The Library of Congress Washington, DC 2005 Contents VOLUME I Foreword to the 1974 Edition . xi Preface to the 2005 Edition . xii Acknowledgments . xiii How to Use This Book . xiv Related Resources . xiv Overall Plan . xiv References to MBC-97 . xiv Using Computer Assistance . xv Taking the Course . xv References . xvi PART ONE: Basic Procedures and Transcribing Single-Staff Music 1 Formation of the Braille Note . 1 2 Eighth Notes, the Eighth Rest, and Other Basic Signs . 3 General Procedures . 4 Examples for Practice . 4 Procedures Specific to This Book . 7 Drills for Chapter 2 . 7 Exercises for Chapter 2 . 9 3 Quarter Notes, the Quarter Rest, and the Dot . 11 Examples for Practice . 11 Proofreading . 13 Drills for Chapter 3 . 13 Exercises for Chapter 3 . 15 4 Half Notes, the Half Rest, and the Tie . 17 Drills for Chapter 4 . 19 Exercises for Chapter 4 . 20 5 Whole and Double Whole Notes and Rests, Measure Rests, and Transcriber-Added Signs . 23 Various Print Methods for Showing Consecutive Measure Rests . 26 Reading Drill . 28 Drills for Chapter 5 . 30 Exercises for Chapter 5 . 31 6 Accidentals . 33 Directions for Brailling Accidentals . 33 Examples for Practice . 34 Drills for Chapter 6 . 35 i Exercises for Chapter 6 . 37 7 Octave Marks . 39 The Seven Octave Marks . -

1 an Important Component of Music Is the Rhythm, Or Duration of The

1 An important component of music is the rhythm, or duration of the sounds. We designate this with whole notes, half notes, quarter notes, eighth notes, etc., the names of which indicate the relative duration of notes (e.g., a half note lasts four times as long as an eighth note). ∼ 3 4 It isd of d courset t necessary to specify the actual (not just relative) duration of sounds. There are several ways to do this, we shall discuss two which reflect the manner in which music is displayed. Printed music groups notes into measures, and begins each line with a time signature which looks like a fraction, and specifies the number of notes in each measure. For example, the time signature 3/4 specifies that each measure contains three quarter notes (or six eighth notes, or a half note and a quarter note, or any collection of notes of equal total duration). (The above schematic is not divided into measures; a whole note would not fit within a measure in 3/4 time.) Indeed, you cannot tell from looking just at a measure whether the time signature is 3/4 or 6/8, but both the top and bottom of the time signature are important for specifying the nature of the rhythm. The top number specifies how many beats (or fundamental time units) there are in a measure, and the bottom number specifies which note represents the fundamental time unit. For example, 3/4 time specifies three beats to a measure with a quarter note representing one beat, 6/8 time specifies six beats to a measure with an eighth note representing one beat. -

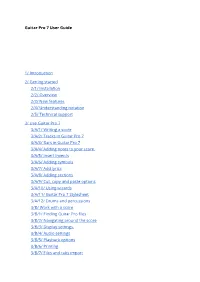

Guitar Pro 7 User Guide 1/ Introduction 2/ Getting Started

Guitar Pro 7 User Guide 1/ Introduction 2/ Getting started 2/1/ Installation 2/2/ Overview 2/3/ New features 2/4/ Understanding notation 2/5/ Technical support 3/ Use Guitar Pro 7 3/A/1/ Writing a score 3/A/2/ Tracks in Guitar Pro 7 3/A/3/ Bars in Guitar Pro 7 3/A/4/ Adding notes to your score. 3/A/5/ Insert invents 3/A/6/ Adding symbols 3/A/7/ Add lyrics 3/A/8/ Adding sections 3/A/9/ Cut, copy and paste options 3/A/10/ Using wizards 3/A/11/ Guitar Pro 7 Stylesheet 3/A/12/ Drums and percussions 3/B/ Work with a score 3/B/1/ Finding Guitar Pro files 3/B/2/ Navigating around the score 3/B/3/ Display settings. 3/B/4/ Audio settings 3/B/5/ Playback options 3/B/6/ Printing 3/B/7/ Files and tabs import 4/ Tools 4/1/ Chord diagrams 4/2/ Scales 4/3/ Virtual instruments 4/4/ Polyphonic tuner 4/5/ Metronome 4/6/ MIDI capture 4/7/ Line In 4/8 File protection 5/ mySongBook 1/ Introduction Welcome! You just purchased Guitar Pro 7, congratulations and welcome to the Guitar Pro family! Guitar Pro is back with its best version yet. Faster, stronger and modernised, Guitar Pro 7 offers you many new features. Whether you are a longtime Guitar Pro user or a new user you will find all the necessary information in this user guide to make the best out of Guitar Pro 7. 2/ Getting started 2/1/ Installation 2/1/1 MINIMUM SYSTEM REQUIREMENTS macOS X 10.10 / Windows 7 (32 or 64-Bit) Dual-core CPU with 4 GB RAM 2 GB of free HD space 960x720 display OS-compatible audio hardware DVD-ROM drive or internet connection required to download the software 2/1/2/ Installation on Windows Installation from the Guitar Pro website: You can easily download Guitar Pro 7 from our website via this link: https://www.guitar-pro.com/en/index.php?pg=download Once the trial version downloaded, upgrade it to the full version by entering your licence number into your activation window. -

Numbers and Tempo: 1630-1800 Beverly Jerold

Performance Practice Review Volume 17 | Number 1 Article 4 Numbers and Tempo: 1630-1800 Beverly Jerold Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons Jerold, Beverly (2012) "Numbers and Tempo: 1630-1800," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 17: No. 1, Article 4. DOI: 10.5642/ perfpr.201217.01.04 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol17/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Numbers and Tempo: 1630-1800 Beverly Jerold Copyright © 2012 Claremont Graduate University Ever since antiquity, the human species has been drawn to numbers. In music, for example, numbers seem to be tangible when compared to the language in early musical texts, which may have a different meaning for us than it did for them. But numbers, too, may be misleading. For measuring time, we have electronic metronomes and scientific instruments of great precision, but in the time frame 1630-1800 a few scientists had pendulums, while the wealthy owned watches and clocks of varying accuracy. Their standards were not our standards, for they lacked the advantages of our technology. How could they have achieved the extremely rapid tempos that many today have attributed to them? Before discussing the numbers in sources thought to support these tempos, let us consider three factors related to technology: 1) The incalculable value of the unconscious training in every aspect of music that we gain from recordings. -

Music Dictionary

Nitschmann Middle School Music Dictionary Principal Words and Symbols used in Modern Music Daniel Zettlemoyer 2010‐2011 # 8va Play the notes indicated up one octave (eight notes higher). 8vb Play the notes indicated one octave lower (eight notes lower). A Accerlerando Gradually increasing in speed, to slowly get faster Accent Emphasis on certain parts of a measure Adagio Slowly, leisurely Ad libitum (ad lib.) Not in strict time A due (a 2) To be played by both instruments Agitato Restless, with agitation Al or Alla In the style of Alla Marcia In the style of a March Allegretto Slower than allegro, moderately fast, faster than andante Allegro Lively, brisk Allegro assai Very rapidly Amoroso Affectionately Andante In moderate slow time Andantino Strictly slower than andante Anima, con Animato With animation A piacere At pleasure; EQuivalent to ad libitum Appassionato Impassioned Arpeggio A broken chord Assai Very, A tempo In the original tempo Attacca Attack or begin what follows without pausing B Barcarolle A Venetian boatman’s song Bis Twice, repeat the passage Bravura Brilliant; bold, spirited Brio, con With much spirit C Cadenza An elaborate, florid passage introduced as an embellishment Cantabile In a singing style Canzonetta A short song or air Capriccio a At pleasure, ad libitum Cavatina An air, shorter and simpler than the aria, and in one division without Da Capo Chord The harmony of three or more tones of different pitch produced simultaneously Coda A supplement at the end of a composition Col or con With Col legno Playing with the wood (bow‐stick) part of the bow. -

Review of Musical Rhythm Symbols and Counting Rhythm Symbols Tell Us How Long a Note Will Be Held

Review of Musical Rhythm Symbols and Counting Rhythm symbols tell us how long a note will be held. Rhythm is measured in beats. This is our unit of measurement in music for rhythm. Some rhythms have a value that is greater than one beat. Here are some examples: Whole Note u The Whole Note is worth four beats of sound. It contains the counts 1, 2, 3, 4. 1 2 3 4 Half Note u The Half Note is worth two beats of sound. It contains the counts 1, 2. 1 2 Dotted Rhythms u The Dotted Half Note is equal to a half note note tied to a quarter note. It has the value of three beats. 3 2 1 u The Dotted Quarter Note is equal to a quarter note tied to an eighth note. It has the value of 1 ½ beats. 1 ½ 1 ½ Rhythms worth one beat: Quarter Note u The Quarter Note is worth one beat. u It has one sound on the beat. u It will have a number as its count. (1, 2, 3 or 4) 1 2 3 4 Rhythms worth one beat: Eighth Notes u Two Eighth Notes are worth one beat. u It has two sounds on the beat. u First note has the # on it. u Second note has + on it 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + Rhythms worth one beat: Sixteenth Notes u Four Sixteenth notes are worth one beat. u It has four sounds on the beat. u First note has the # on it. u Second note has “e” on it.