Hedi El Kholti / Hold up to the Light

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aztec Camera: Discography Albums Articles Audio B-Sides Discography Guestbook Tabs Images Info Links Search Home

Aztec Camera: Discography albums articles audio b-sides discography guestbook tabs images info links search home Discography & Videography Thanks to Phillip Gauthier, Roger Boge and the Aztec Camera Information Service. Just Like Gold January 1981 Just Like Gold ( Lyrics | Audio ) Postcard Catalog # 81-3 U.K. 7 inch We Could Send Letters ( Lyrics ) Mattress of Wire May 1981 ( Sleeve ) Postcard Catalog # 81-8 ( Lyrics | Audio ) U.K. 7 inch Mattress of Wire Lost Outside the Tunnel ( Lyrics ) Pillar to Post September 1982 ( Sleeve ) Rough Trade # RT 112 ( Lyrics ) U.K. 7 inch Pillar to Post Queens Tattoos ( Lyrics ) http://www.aoinfo.com/aztec/html/disc.htm (1 of 14) [1/29/2000 5:34:54 PM] Aztec Camera: Discography Rough Trade # RT 112P [ picture disc ] U.K. 7 inch Oblivious January 1983 Oblivious ( Lyrics ) Rough Trade # RT 122 U.K. 7 inch Orchid Girl ( Lyrics ) Rough Trade # RT 122T Oblivious (remix) Sire # 020219 Orchid Girl U.K. 12 inch Haywire ( Lyrics ) Walk Out to Winter April 1983 Walk Out to Winter ( Lyrics ) Rough Trade # RT 132 U.K. 7 inch Set the Killing Free ( Lyrics ) Rough Trade # RT 132T Walk Out to Winter (extended remix) U.K. 12 inch Set the Killing Free High Land, Hard Rain April 1983 U.K. LP Rough Trade # 47 See ( Info ) for track listings, lyrics, performers, etc. ( Info ) U.S. LP Sire U.K. CD Rough Trade CD adds the following tracks: U.S. CD Sire Haywire, Orchid Girl and Queens Tattoos Oblivious (second release) October 1983 Oblivious (remix) WEA # AZTEC 1 U.K. -

PDF (V. 86:21, March 15, 1985)

COV\q(~UI~6)\SJ CCfl..'\~ THE ro.:h!\lrl-r0\1\S I K~r-lo.\. CALIFORNIA ::red \. VOLUME 86 PASADENA, CALIFORNIA / FRIDAY 15 MARCH 1985 NUMBER ~1 Admiral Gayler Speaks On The Way Out by Diana Foss destroyed just as easily by a gravi- Last Thursday, the Caltech ty bomb dropped from a plane as Distinguished Speakers Fund, the by a MIRVed ICBM. In fact, Caltech Y, and the Caltech World technology often has a highly Affairs Forum jointly sponsored a detrimental effect. Improved ac talk by Admiral Noel Gayler entitl- curacy of nuclear missles has led ed, "The Way Out: A General to the ability to target silos with Nuclear Settlement." The talk, pinpoint precision. This leads to the which was given in Baxter Lecture dangerous philosophy of "use Hall, drew about sixty people, them or lose them," with such mainly staff, faculty, and graduate manifestations as preemptive students, with a sprinkling of strikes and launch-on-warning undergraduates. President systems. Goldberger introduced Admiral While Gayler views as laudable 15' Gayler, who is a former Com- Reagan's attempts to find a more :tl mander in Chiefofthe Pacific Fleet "humane" policy than Mutually ~ and a former director of the Na- Assured Detruction, he sees the ~ tional Security Agency. Space Defense Initiative as a .s Gayler began his talk by em- fruitless attempt to use technology ~ phasizing the. threat of the huge to work impossible miracles, part -a nuclear stockpiles of the two super- of a general trend to make science I powers. The numbers themselves, an omnipotent god. -

LONG ISLAND WEEKLY Lpublished by Anton Mediai Group • Mwarch 23 - 29, 2016 Vol

1 LONG ISLAND WEEKLY LPublished by Anton MediaI Group • MWarch 23 - 29, 2016 Vol. 3, No. 11 $1.00 LongIslandWeekly.com EXCLUSIVE SouthernAmericana bard Lucinda Gothic Williams SEE OUR 2016 SPRING CAMPAIGN INSIDE ON THE BACK COVER. BROADWAY’S LOVE AFFAIR WITH PARIS GERMAN FOOD IS WUNDERBAR AT PLATTDUETSCHE SPECIAL SECTION: BANKING & FINANCE YEARS 4A ANTON MEDIA GROUP • MARCH 23 - 29, 2016 Visiting The Ghosts Of Highway 20 Lucinda Williams takes a musical trip into her past Lucinda Williams (Photo by David McClister) BY DAVE GIL DE RUBIO vocation as a visiting college professor— project. It’s particularly effective on music. It’s an exercise she did on the last [email protected] places like Vicksburg, MS, and Minden, character-driven fare like the sleepy record via the gorgeous acoustic opener LA—Williams has recorded 14 songs jazz arrangement that tells the tale of a “Compassion.” As she admits, transpos- In the 1968 song, “Salt of the Earth,” populated by the same kinds of blue junkie in “I Know All About It” and the ing from a poem to a song is an inexact the Rolling Stones once sang, “Let’s collar individuals she came to know bluesy “Doors of Heaven,” which finds science she’s getting the hang of. drink to the hard working people/ growing up in the Deep South. Williams taking on the world-weary “That’s the thing, when you’re Let’s think of the lowly of birth/Spare a The Louisiana native and her long- voice of a dying person ready to singing, the words kind of have to roll thought for the rag taggy people/Let’s time rhythm section of David Sutton move on. -

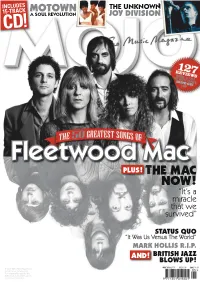

Mojoearlier Results Are Tremendous

INCLUDES MOTOWN THE UNKNOWN 15-TRACK A SOUL REVOLUTION JOY DIVISION CD! Y PLUS! HE MAC NOW! “It’s a miracle that we survived” STATUS QUO MARK HOLLIS R.I.P. AND! BRITISH JAZZ BLOWS UP! MAY 2019 £5.75 US$11.99 CAN$14.99 If your CD is missing please inform your newsagent. For copyright reasons the CD is not available in some overseas territories. Lias Saoudi, torch-carrying FILTER ALBUMS provocateur. These New hypnosis rule, though, remains town (the New York strut of duet of self-destruction. After to be seen. Enlightening 2017’s City Music). With Oh My all of it, JPW is left at the sink, Puritans nevertheless. God, Morby launches a more repeating, “Your love’s the ★★ Charles Waring overtly spiritual quest, hurting kind,” unable or investigating the tensions unwilling to give it up. Inside The Rose between the sacred and Chris Nelson INFECTIOUS MUSIC. CD/DL/LP profane – or “horns on my Underwhelming fourth Our Native head, wings from my album from Southend Daughters shoulder,” as he puts it on The Cranberries erstwhile avant-garde ★★★★ O Behold. A blast of Mary world-beaters Lattimore’s harp on Piss River #### SongsOfOur or Savannah’s glassy Dirty Slimmed down In The End Native Daughters Projectors-style choir hint at to the core the celestial, but if Morby BMG. CD/DL/LP fraternal duo SMITHSONIAN FOLKWAYS. CD/DL Edwyn Collins speaks in tongues, they are still Final album, with Step of Jack and New history from onet very much those of Bob Dylan #### Street back producing George Barnett leader of the Carolina and Leonard Cohen – earthly, after the 2016 Chocolate Drops. -

“9” Just Short of a Perfect 10

6 AQUINAS THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 17, 2009 7 Arts & Life Editor Joe Wolfe Brand New’s darker “Daisy” VMAs still full Campus Comment COMMentarY BY Arts Life Nicholas Chinman Dervela O’BRIEN of surprises & Staff Writer In the aftermath of the West Fans of the alternative-rock COMMentarY BY incident, Swift stunned the audi- band, Brand New, are anxiously TIM SIMpsON ence with her live performance. Download awaiting the release of the band’s Staff Writer She sang her award winning “9” just short of a perfect 10 fourth album entitled “Daisy,” single “You Belong with Me” in a which is scheduled to be released On September 13, the 2009 crowded New York City subway of the September 22. After almost three MTV Video Music Awards took COMMentarY BY with fans providing the back- years of touring and writing new place at Radio City Music Hall ground vocals to her tune. She JEREMY Evans material since their well-received in New York City. For the sec- week glowed with enthusiasm while Staff Writer “The Devil and God Are Raging ond consecutive year, the event spinning around in circles, danc- Inside Me,” the Long Island native was hosted by comedian Russell ing on the seats and involving In 2005, Shane Acker created band has worked hard to put to- Brand. several members of the crowd an animated short as a student “Pale Blue gether their latest album, which is The night began with a heart- in her upbeat performance. Af- project. He crafted a fascinating sure to surprise its listeners. felt speech delivered by Madon- ter leaving the subway, she and world, one which caught the at- “Daisy” follows many of the na in honor of her late friend Mi- PHOTO BY BRAND NEW MYSPACE PAGE her fans ran to the front of Radio tention of many in the film-mak- Eyes” same dark philosophical themes chael Jackson. -

Michele Mulazzani's Playlist: Le 999 Canzoni Piu' Belle Del XX Secolo

Michele Mulazzani’s Playlist: le 999 canzoni piu' belle del XX secolo (1900 – 1999) 001 - patti smith group - because the night - '78 002 - clash - london calling - '79 003 - rem - losing my religion - '91 004 - doors - light my fire - '67 005 - traffic - john barleycorn - '70 006 - beatles - lucy in the sky with diamonds - '67 007 - nirvana - smells like teen spirit - '91 008 - animals - house of the rising sun - '64 009 - byrds - mr tambourine man - '65 010 - joy division - love will tear us apart - '80 011 - crosby, stills & nash - suite: judy blue eyes - '69 012 - creedence clearwater revival - who'll stop the rain - '70 013 - gaye, marvin - what's going on - '71 014 - cocker, joe - with a little help from my friends - '69 015 - fleshtones - american beat - '84 016 - rolling stones - (i can't get no) satisfaction - '65 017 - joplin, janis - piece of my heart - '68 018 - red hot chili peppers - californication - '99 019 - bowie, david - heroes - '77 020 - led zeppelin - stairway to heaven - '71 021 - smiths - bigmouth strikes again - '86 022 - who - baba o'riley - '71 023 - xtc - making plans for nigel - '79 024 - lennon, john - imagine - '71 025 - dylan, bob - like a rolling stone - '65 026 - mamas and papas - california dreamin' - '65 027 - cure - charlotte sometimes - '81 028 - cranberries - zombie - '94 029 - morrison, van - astral weeks - '68 030 - springsteen, bruce - badlands - '78 031 - velvet underground & nico - sunday morning - '67 032 - modern lovers - roadrunner - '76 033 - talking heads - once in a lifetime - '80 034 -

Issue 184.Pmd

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 184 November Oxford’s Music Magazine 2010 Oxford’s Greatest Metal Bands Ever Revealed! photos: rphimagies The METAL!issue featuring Desert Storm Sextodecimo JOR Sevenchurch Dedlok Taste My Eyes and many more NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net COMMON ROOM is a two-day mini-festival taking place at the Jericho Tavern over the weekend of 4th-5th December. Organised by Back & To The Left, the event features sets from a host of local bands, including Dead Jerichos, The Epstein, Borderville, Alphabet Backwards, Huck & the Handsome MOTOWN LEGENDS MARTHA REEVES & THE VANDELLAS play Fee, The Yarns, Band of Hope, at the O2 Academy on Sunday 12th December. Reeves initially retired Spring Offensive, Our Lost Infantry, from performing in 1972 due to illness and had until recently been a Damn Vandals, Minor Coles, The member of Detroit’s city council. In nine years between 1963-72 the trio Scholars, Samuel Zasada, The had 26 chart hits, including the classic `Dancing In The Streets’, `Jimmy Deputees, Message To Bears, Above Mack’ and `Heatwave’. Tickets for the show are on sale now, priced £20, Us The Waves, The Gullivers, The from the Academy box office an online at www.o2academyoxford.co.uk. DIVE DIVE have signed a deal with Moulettes, Toliesel, Sonny Liston, Xtra Mile Records, home to Frank Cat Matador and Treecreeper. Early Turner, with whom they are bird tickets, priced £8 for both days, on Friday 19th November, with be released and the campaign bandmates, and fellow Oxford stars A are on sale now from support from Empty Vessels plus culminates with the release of ‘Fine Silent Film. -

Atravessar O Fogo 310 Letras

LOU REED Atravessar o fogo 310 letras Tradução Christian Schwartz e Caetano W. Galindo 12758-atravessarofogo.indd 3 7/5/10 4:43:29 PM Copyright © 2000 by Lou Reed. Todos os direitos reservados Grafia atualizada segundo o Acordo Ortográfico da Língua Portuguesa de 1990, que entrou em vigor no Brasil em 2009. Título original Pass thru fire – The collected lyrics Capa Jeff Fischer Preparação Alexandre Boide Revisão Huendel Viana Marina Nogueira Dados Internacionais de Catalogação na Publicação (CIP ) (Câmara Brasileira do Livro, SP , Brasil) Reed, Lou Atravessar o fogo : 310 letras / Lou Reed ; tradução Christian Schwartz e Caetano W. Galindo — São Paulo : Companhia das Letras, 2010. Título original : Pass thru fire : the collected lyrics. ISBN 978-85-359-1697-3 1. Letras de música 2. Música rock - Letras I. Título. 10-05405 CDD -782.42166 Índice para catálogo sistemático: 1. Rock : Letras de música 782.42166 [2010] Todos os direitos desta edição reservados à EDITORA SCHWARCZ LTDA . Rua Bandeira Paulista 702 cj. 32 04532-002 — São Paulo — SP Tel. (11) 3707-3500 Fax (11) 3707-3501 www.companhiadasletras.com.br 12758-atravessarofogo.indd 4 7/5/10 4:43:29 PM Sumário 19 Prefácio à edição da Da Capo Press 21 Introdução — Atravessar o fogo 23 Nota sobre a tradução THE VELVET UNDERGROUND & NICO 26/ 501 Domingo de manhã/ Sunday morning 27/ 501 Estou esperando o cara/ I’m waiting for the man 28/ 502 Femme fatale/ Femme fatale 29/ 503 A Vênus das peles/ Venus in furs 30/ 503 Corra corra corra/ Run run run 31/ 504 Todas as festas de amanhã/ All tomorrow’s -

Une Discographie De Robert Wyatt

Une discographie de Robert Wyatt Discographie au 1er mars 2021 ARCHIVE 1 Une discographie de Robert Wyatt Ce présent document PDF est une copie au 1er mars 2021 de la rubrique « Discographie » du site dédié à Robert Wyatt disco-robertwyatt.com. Il est mis à la libre disposition de tous ceux qui souhaitent conserver une trace de ce travail sur leur propre ordinateur. Ce fichier sera périodiquement mis à jour pour tenir compte des nouvelles entrées. La rubrique « Interviews et articles » fera également l’objet d’une prochaine archive au format PDF. _________________________________________________________________ La photo de couverture est d’Alessandro Achilli et l’illustration d’Alfreda Benge. HOME INDEX POCHETTES ABECEDAIRE Les années Before | Soft Machine | Matching Mole | Solo | With Friends | Samples | Compilations | V.A. | Bootlegs | Reprises | The Wilde Flowers - Impotence (69) [H. Hopper/R. Wyatt] - Robert Wyatt - drums and - Those Words They Say (66) voice [H. Hopper] - Memories (66) [H. Hopper] - Hugh Hopper - bass guitar - Don't Try To Change Me (65) - Pye Hastings - guitar [H. Hopper + G. Flight & R. Wyatt - Brian Hopper guitar, voice, (words - second and third verses)] alto saxophone - Parchman Farm (65) [B. White] - Richard Coughlan - drums - Almost Grown (65) [C. Berry] - Graham Flight - voice - She's Gone (65) [K. Ayers] - Richard Sinclair - guitar - Slow Walkin' Talk (65) [B. Hopper] - Kevin Ayers - voice - He's Bad For You (65) [R. Wyatt] > Zoom - Dave Lawrence - voice, guitar, - It's What I Feel (A Certain Kind) (65) bass guitar [H. Hopper] - Bob Gilleson - drums - Memories (Instrumental) (66) - Mike Ratledge - piano, organ, [H. Hopper] flute. - Never Leave Me (66) [H. -

1965 Falling Spikes: a Fake Tape

Source/Title: FallingSpikes 1965 The text says: FALLING SPIKES LOU REED, JOHN CALE, STERLING MORRISON, ANGUS MACLISE IN 1965 A NEW YORK BAND CALLED THE PRIMITIVES CHANGED IT'S NAME TO THE WARLOCKS AND THEN TO THE FALLING SPIKES, LATER TO BECOME FAMOUS AS THE VELVET UNDERGROUND. THIS RARE RECORDING FROM 1965 IS THEIR ONLY RECORDED WORK. Actually: it's a tape copy of the "Live at the Boston Tea Party" LP (catalogue Velvet 1, UK, 1985) but the album Side One is the tape B-Side (and Side Two becomes the A-Side). Tracklist (not given on sleeve insert): A-Side B-Side Heroin What Goes On (the rest) Move Right In I Can't Stand It I'm Set Free Candy Says Run Run Run Beginning to See the Light Waiting for the Man White Light/White Heat What Goes On (part) Pale Blue Eyes After Hours Equivalent: Tape 3, VU LIVE - BOSTON TEA PARTY (JAN. 10, 1969) (but it's a loose equivalent). Sound: Bad to Average. Side B is too fast, like the album, with clicks and tape whirrs on "Candy Says" and is basically unlistenable. Side A is average at best. Notes: What a gem this would have been, but it's either a bad joke or a deliberate fraud. The sleeve insert is badly copied and hand-cut with blunt scissors, the text says "IT'S" when it should be "ITS", there is no Cale or Maclise and sloppy copying splits WGO over two sides needlessly with the first part lasting just a few seconds. -

The Snow Miser Song 6Ix Toys - Tomorrow's Children (Feat

(Sandy) Alex G - Brite Boy 1910 Fruitgum Company - Indian Giver 2 Live Jews - Shake Your Tuchas 45 Grave - The Snow Miser Song 6ix Toys - Tomorrow's Children (feat. MC Kwasi) 99 Posse;Alborosie;Mama Marjas - Curre curre guagliò still running A Brief View of the Hudson - Wisconsin Window Smasher A Certain Ratio - Lucinda A Place To Bury Strangers - Straight A Tribe Called Quest - After Hours Édith Piaf - Paris Ab-Soul;Danny Brown;Jhene Aiko - Terrorist Threats (feat. Danny Brown & Jhene Aiko) Abbey Lincoln - Lonely House - Remastered Abbey Lincoln - Mr. Tambourine Man Abner Jay - Woke Up This Morning ACID MOTHERS TEMPLE - Are We Experimental? Adolescents - Democracy Adrian Sherwood - No Dog Jazz Afro Latin Vintage Orchestra - Ayodegi Afrob;Telly Tellz;Asmarina Abraha - 808 Walza Afroman - I Wish You Would Roll A New Blunt Afternoons in Stereo - Kalakuta Republik Afu-Ra - Whirlwind Thru Cities Against Me! - Transgender Dysphoria Blues Aim;Qnc - The Force Al Jarreau - Boogie Down Alabama Shakes - Joe - Live From Austin City Limits Albert King - Laundromat Blues Alberta Cross - Old Man Chicago Alex Chilton - Boplexity Alex Chilton;Ben Vaughn;Alan Vega - Fat City Alexia;Aquilani A. - Uh La La La AlgoRythmik - Everybody Gets Funky Alice Russell - Humankind All Good Funk Alliance - In the Rain Allen Toussaint - Yes We Can Can Alvin Cash;The Registers - Doin' the Ali Shuffle Amadou & Mariam - Mon amour, ma chérie Ananda Shankar - Jumpin' Jack Flash Andrew Gold - Thank You For Being A Friend Andrew McMahon in the Wilderness - Brooklyn, You're -

{PDF EPUB} the Velvet Underground - 45Th Anniversary Super Deluxe Edition by David Fricke MQS Albums Download

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} The Velvet Underground - 45th Anniversary Super Deluxe Edition by David Fricke MQS Albums Download. Mastering Quality Sound,Hi-Res Audio Download, 高解析音樂, 高音質の音楽. The Velvet Underground – The Velvet Underground (45th Anniversary Super Deluxe) (1969/2014) [FLAC 24bit/96kHz] The Velvet Underground – The Velvet Underground (45th Anniversary Super Deluxe) (1969/2014) FLAC (tracks) 24 bit/96 kHz | Time – 05:20:48 minutes | 6,16 GB | Genre: Rock Studio Masters, Official Digital Download | Front Cover | © Polydor. The Velvet Underground’s classic self-titled third album, released in March 1969, by MGM, was a departure from the band’s first two albums in more ways than one. Gone was co-founding member John Cale, and in his place was a 21-year-old with Long Island roots named Doug Yule, who stepped right in. The record was also a stylistic leap, as Lou Reed describes it in Rolling Stone editor David Fricke’s liner notes, “I thought we had to demonstrate the other side of us. Fricke calls it “a stunning turnaround… 10 tracks of mostly warm, explicit sympathy and optimism, expressed with melodic clarity, set in gleaming double-guitar jangle and near-whispered balladry. Or as the late rock critic Lester Bangs put it, “How do you define a group like this, who moved from ‘Heroin’ to ‘Jesus’ in two short years?” How indeed do you describe an album which includes such classics as “Candy Says,” Reed’s ode to Warhol superstar Candy Darling; the aching love song “Pale Blue Eyes,” allegedly inspired by a girlfriend at Syracuse University who got away, with lead vocals by Yule; the inspiring “Beginning to See The Light”; the spoken-word narrative and musique concrete of “The Murder Mystery,” and the beautiful Maureen Tucker-sung “After Hours”? Celebrating its enduring longevity, Polydor/Universal Music Enterprises (UMe) has released The Velvet Underground – 45th Anniversary Super Deluxe Edition.