CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE Gian Carlo Menotti

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8.112023-24 Bk Menotti Amelia EU 26-03-2010 9:41 Pagina 16

8.112023-24 bk Menotti Amelia_EU 26-03-2010 9:41 Pagina 16 Gian Carlo MENOTTI Also available The Consul • Amelia al ballo LO M CAR EN N OT IA T G I 8.669019 19 gs 50 din - 1954 Recor Patricia Neway • Marie Powers • Cornell MacNeil 8.669140-41 Orchestra • Lehman Engel Margherita Carosio • Rolando Panerai • Giacinto Prandelli Chorus and Orchestra of La Scala, Milan • Nino Sanzogno 8.112023-24 16 8.112023-24 bk Menotti Amelia_EU 26-03-2010 9:41 Pagina 2 MENOTTI CENTENARY EDITION Producer’s Note This CD set is the first in a series devoted to the compositions, operatic and otherwise, of Gian Carlo Menotti on Gian Carlo the occasion of his centenary in 2011. The recordings in this series date from the mid-1940s through the late 1950s, and will feature several which have never before appeared on CD, as well as some that have not been available in MENOTTI any form in nearly half a century. The present recording of The Consul, which makes its CD début here, was made a month after the work’s (1911– 2007) Philadelphia première. American Decca was at the time primarily a “pop” label, the home of Bing Crosby and Judy Garland, and did not yet have much experience in the area of Classical music. Indeed, this recording seems to have been done more because of the work’s critical acclaim on the Broadway stage than as an opera, since Decca had The Consul also recorded Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman with members of the original cast around the same time. -

THE BROOKLYN PHILHARMONIA 27Th Season: 1980/1981 LUKAS FOSS, Music Director

THEOOOPER~ONFORUM November 14, 1980, Spm THE BROOKLYN PHILHARMONIA 27th Season: 1980/1981 LUKAS FOSS, Music Director MEET THE MODERNS 1: MUSIC + DRAMA two one-act operas THE CRY OF CLYTAEMNESTRA THE EGG Music by John Eaton an operatic riddle Libretto by Patrick Creagh Music and Libretto by Gian Carlo Menotti New York premiere New York premiere RICHARD DUNCAN, conductor LUKAS FOSS, conductor Staging by Maurice Edwards Staging by Maurice Edwards Lighting by William Mintzer Lighting by William Mintzer Sound Co-ordinator: Lonnie Juli Costumes by Constance Mellen Cast Cast (in o rder of appearance) (in o rder of appearance) ClytaernJlt'~tra Quec•11 o{ Ar,J~e>S . elcla elson Manuel ................................... Martin Strother lphygene1a eldest dau,J~hter o{ C/ytaemnestra St Simeon Stylites .............................joseph Levitt !111(/ A.I!Cllll£'11111011 . • • • . • . • Sally Wolf BasJIJssa Empress o{ ByzantiUm ( Pnde} . ............ Edith Diggory Agamemnon KJII,JI of ArJioS . • . • • . Tim o ble Areobindus. {avonte o{the Bas111ssa (Lust} .......... Steven Nelson Ody~seus . Ri chard Walker Gourmantus, the cook (Gluttony} . ....... ........ Ted Adkins Menelaus . ·- . Brian Trego Eunuch of the Sacred Cubicle !Slot hi ............ Richard Walker DJOilll'tks . Martin Strother Pachomius. the treasurer (A vance} . .................. Jon Fay TnKer . Steven Nelson Sister of the BasJIJssa !Envyl . ...... ............... Paula Redd Calcha~. HlJih Pnest. joseph Levitt Julian, Capt am o{ the Guard (Anger} (silent role} . .. ..... Brian Trego Acl11llcs . .Jon Fay Beggar Woman . ... .............. Sarah Miller Electra. dauxhter o{ C/ytaem11estra and !Chorusl ............ Axamemncm. as a ch1ld . ................. .. ....... Abby Tate Members of the Basi IIssa's Court Sally Wolf, Martha Waltman Rebecca Field, Glenn Siebert, Colenton Freeman Orestes. so11 o{ Clytaem>lestra and Agamemnon, as a child . -

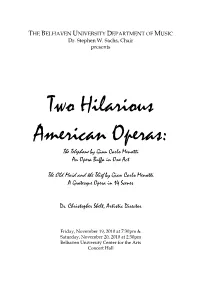

The Old Maid and the Thief by Gian Carlo Menotti a Grotesque Opera in 14 Scenes

THE BELHAVEN UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC Dr. Stephen W. Sachs, Chair presents Two Hilarious American Operas: The Telephone by Gian Carlo Menotti An Opera Buffa in One Act The Old Maid and the Thief by Gian Carlo Menotti A Grotesque Opera in 14 Scenes Dr. Christopher Shelt, Artistic Director Friday, November 19, 2010 at 7:30pm & Saturday, November 20, 2010 at 2:30pm Belhaven University Center for the Arts Concert Hall BELHAVEN UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC MISSION STATEMENT The Music Department seeks to produce transformational leaders in the musical arts who will have profound influence in homes, churches, private studios, educational institutions, and on the concert stage. While developing the God-bestowed musical talents of music majors, minors, and elective students, we seek to provide an integrative understanding of the musical arts from a Christian world and life view in order to equip students to influence the world of ideas. The music major degree program is designed to prepare students for graduate study while equipping them for vocational roles in performance, church music, and education. The Belhaven University Music Department exists to multiply Christian leaders who demonstrate unquestionable excellence in the musical arts and apply timeless truths in every aspect of their artistic discipline. The Music Department would like to thank our many community partners for their support of Christian Arts Education at Belhaven University through their advertising in “Arts Ablaze 2010-2011” (should be published and available on or before September 30, 2010). Special thanks tonight to Bo-Kays Florist for our reception table flowers. It is through these and other wonderful relationships in the greater Jackson community that makes an afternoon like this possible at Belhaven. -

April 2008 in This Issue

The Sacred in Opera April 2008 In this Issue... Ruth Dobson For the next two editions of the SIO newsletter, we are taking an in-depth look at one-act Christmas operas which can be easily produced and are appropriate for both children and adults. This issue we will profile Amahl and the Night Visitors, Only a Miracle, St. Nicholas, Good King Wenceslas, and The Shepherd’s Play. The next issue will highlight The Christmas Rose, The Greenfield Christmas Tree, The Finding of the King, The Night of the Star, and others. Thanks to Allen Henderson for sharing his insight into a triology of operas by Richard Shephard, Good King Wenceslas, The Shepherd’s Play, and St. Nicholas, with us in this issue. As great as Amahl and the Night Visitors is, there are these and other works waiting to be discovered by all of us. We hope you will find these suggestions interesting. These operas vary in length from 10 minutes to an hour, and can be presented alone or paired with others. Amahl and the Night Visitors is almost always a successful box office draw. Pairing it with a lesser known work could make for a very enjoyable afternoon or evening presentation and give audiences an opportunity to enjoy other equally wonderful works. Several of these operas use children as cast members, while others call for only adult performers, but all have stories appropriate for children. They are written in a variety of styles and have very different production requirements. Producers would need to take into consideration the ages of the children that are the target audience. -

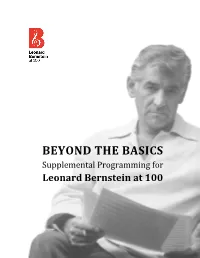

BEYOND the BASICS Supplemental Programming for Leonard Bernstein at 100

BEYOND THE BASICS Supplemental Programming for Leonard Bernstein at 100 BEYOND THE BASICS – Contents Page 1 of 37 CONTENTS FOREWORD ................................................................................. 4 FOR FULL ORCHESTRA ................................................................. 5 Bernstein on Broadway ........................................................... 5 Bernstein and The Ballet ......................................................... 5 Bernstein and The American Opera ........................................ 5 Bernstein’s Jazz ....................................................................... 6 Borrow or Steal? ...................................................................... 6 Coolness in the Concert Hall ................................................... 7 First Symphonies ..................................................................... 7 Romeos & Juliets ..................................................................... 7 The Bernstein Beat .................................................................. 8 “Young Bernstein” (working title) ........................................... 9 The Choral Bernstein ............................................................... 9 Trouble in Tahiti, Paradise in New York .................................. 9 Young People’s Concerts ....................................................... 10 CABARET.................................................................................... 14 A’s and B’s and Broadway .................................................... -

Westchester Music Man Harold Rosenbaum Shares His Alphabetical Favorites

Subscribe Digital Edition Give a Gift Customer Service WestchesterBest Places To Live Today's Music News What To Do ManLocal Business Harold Guide Blogs Real Estate Top Doctors Top Dentists High School Chart Take Our Reader Survey Rosenbaum Shares His Alphabetical Favorites ® County people and places that strike a chord with renowned choral conductor Harold Rosenbaum. BY HAROLD ROSENBAUM; LLUSTRATION BY CAITLIN KUHWALD EAT & DRINK LIFE & STYLE ARTS & CULTURE INSIDER GUIDES BEST OF WESTCHESTER® Facebook Twitter Google+ Pinterest Ancient houses. Not by European RELATED STORIES standards, but who cares? Barber in Cross River, who also replaces watchbands. It reminds me of the Wild West, where barbers also extracted teeth! Copland House in Cortlandt Manor. Yes, Aaron actually lived there. I conducted his choral Urban Planning Pioneer Seeks To Upgrade masterpiece In the Beginning at his 80th birthday Playland celebration at Symphony Space in NYC. Dirt roads. Sure, they can be a muddy mess when it rains, but they are a nice reminder of our past. Edie, my amazing, talented, beautiful, kind wife, who, among many other things, runs our youth choir, The Canticum Novum Singers. How Baseball Sparked Doris Kearns Goodwin's Love Of History Farms. Real ones. One can join some of them to obtain organic produce weekly. Grandsons. My three—who force me to be normal at times (well, at least goofy and regressive). Horse & Hound Inn, which accommodates my diet every time (I haven’t had meat, fish, dairy, or grains for decades). Idealists. There are plenty of them here, with solar panels, food-producing farm animals, and world-class gardens. -

Distribution Agreement in Presenting This Thesis As A

Distribution Agreement In presenting this thesis as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for a degree from Emory University, I hereby grant to Emory University and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive, make accessible, and display my thesis in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter now, including display on the World Wide Web. I understand that I may select some access restrictions as part of the online submission of this thesis. I retain all ownership rights to the copyright of the thesis. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis. Naomi P. Newton April 12, 2016 Storytelling In Opera, Operetta, and American Musical Theater A Research-Performance Honors Thesis by Naomi P. Newton Kristin Wendland, PhD Adviser Bradley Howard, MM Adviser Department of Music Kristin Wendland, PhD Adviser Bradley Howard, MM Adviser Stephen Crist, PhD Committee Member Arri Eisen, PhD Committee Member 2016 Storytelling In Opera, Operetta, and American Musical Theater A Research-Performance Honors Thesis By Naomi P. Newton Kristin Wendland, PhD Adviser Bradley Howard, MM Adviser Department of Music An abstract of a thesis submitted to the Faculty of Emory College of Arts and Sciences of Emory University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors. Department of Music 2016 Abstract Storytelling In Opera, Operetta, and American Musical Theater A Research-Performance Honors Thesis By Naomi P. Newton This thesis represents one aspect of my dual research-performance honors project. -

SOME AMERICAN OPERAS/COMPOSERS October 2014

SOME AMERICAN OPERAS/COMPOSERS October 2014 Mark Adamo-- Little Women, Lysistrata John Adams—Nixon in China, Death of Klinghoffer, Doctor Atomic Dominick Argento—Postcard From Morocco, The Aspern Papers William Balcom—A View From the Bridge, McTeague Samuel Barber—Antony and Cleopatra, Vanessa Leonard Bernstein— A Quiet Place, Trouble in Tahiti Mark Blitzstein—Regina, Sacco and Venzetti, The Cradle Will Rock David Carlson—Anna Karenina Aaron Copland—The Tender Land John Corigliano—The Ghosts of Versailles Walter Damrosch—Cyrano, The Scarlet Letter Carlisle Floyd—Susannah, Of Mice and Men, Willie Stark, Cold Sassy Tree Lukas Foss—Introductions and Goodbyes George Gershwin—Porgy and Bess Philip Glass—Satyagraha, The Voyage, Einstein on the Beach, Akhnaten Ricky Ian Gordon—Grapes of Wrath Louis Gruenberg—The Emperor Jones Howard Hanson—Merry Mount John Harbison—The Great Gatsby, Winter’s Tale Jake Heggie—Moby Dick, Dead Man Walking Bernard Hermann—Wuthering Heights Jennifer Higdon—Cold Mountain (World Premiere, Santa Fe Opera, 2015) Scott Joplin—Treemonisha Gian Carlo Menotti—The Consul, The Telephone, Amahl and the Night Visitors Douglas Moore—Ballad of Baby Doe, The Devil and Daniel Webster, Carrie Nation Stephen Paulus—The Postman Always Rings Twice, The Woodlanders Tobias Picker—An American Tragedy, Emmeline, Therese Racquin Andre Previn—A Streetcar Named Desire Ned Rorem—Our Town Deems Taylor—Peter Ibbetson Terry Teachout—The Letter Virgil Thompson—Four Saints in Three Acts, The Mother of Us All Stewart Wallace—Harvey Milk Kurt Weill—Street Scene, Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny . -

Program Notes | Amahl and the Night Visitors

23 Season 2018-2019 Thursday, December 13, at 7:30 The Philadelphia Orchestra Saturday, December 15, at 8:00 Bramwell Tovey Conductor and Narrator Dante Michael DiMaio Boy Soprano (Amahl) Renée Tatum Mezzo-soprano (His Mother) Andrew Stenson Tenor (King Kaspar) Brandon Cedel Bass-baritone (King Melchior) David Leigh Bass (King Balthazar) Kirby Traylor Bass (The Page) Philadelphia Symphonic Choir (Shepherds and Villagers) Amanda Quist Director Omer Ben Seadia Stage Director Walton Crown Imperial (Coronation March) Britten The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra, Op. 34 Intermission Menotti Amahl and the Night Visitors First complete Philadelphia Orchestra performances Ryan Howell, designer Chris Frey, lighting desig This program runs approximately 1 hour, 45 minutes. These concerts are part of the Fred J. Cooper Memorial Organ Experience, supported through a generous grant from the Wyncote Foundation. The December 15 concert is sponsored by Medcomp. Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM, and are repeated on Monday evenings at 7 PM on WRTI HD 2. Visit www.wrti.org to listen live or for more details. PO Book 16_Home.indd 23 12/7/18 10:35 AM 24 The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin The Philadelphia Orchestra Philadelphia is home and orchestra, and maximizes is one of the preeminent the Orchestra continues impact through Research. orchestras in the world, to discover new and The Orchestra’s award- renowned for its distinctive inventive ways to nurture winning Collaborative sound, desired for its its relationship with its Learning programs engage keen ability to capture the loyal patrons at its home over 50,000 students, hearts and imaginations of in the Kimmel Center, families, and community audiences, and admired for and also with those who members through programs a legacy of imagination and enjoy the Orchestra’s area such as PlayINs, side-by- innovation on and off the performances at the Mann sides, PopUP concerts, concert stage. -

Nita Ann Hudson, Mezzo Soprano School of Music Stephen F

Nita Ann Hudson, mezzo soprano School of Music Stephen F. Austin State University Nacogdoches, Texas Education Master of Arts Stephen F. Austin State University, 1993 Major in Music with Vocal Pedagogy Emphasis Bachelor of Music Stephen F. Austin State University, 1990 All-Level certification in Choral Music Applied Voice Richard Berry Vocal Pedagogy David W. Jones Richard Berry Choral Conducting Ronald Anderson Tim King Theory/Composition Richard Coolidge Dan Beaty Dance Deborah Waddell-Sanford Teaching Teaching Positions: Stephen F. Austin State University, Nacogdoches, TX: 1993 – Present Lecturer – Applied Voice, Opera Workshop, Vocal Repertoire, Theory, Aural Skills East Texas Baptist State University, Marshall, TX: 1994 – 2002 Instructor – Applied Voice Related Work Experience: Assistant Director/Production Stage Manager, SFASU Opera Workshop: 1993 - Present Assignment includes various aspects of stage directing, production and choreography. Coordinate all rehearsal and production schedules for faculty, students, orchestra, and technical crews. Responsible for maintaining the correct blocking (prompt book) and all technical cues (scenic/lighting/sound). Assist the directors (staging/musical) in every aspect of production. Operas/Operettas: Albert Herring (Britten) 1993 Amelia Goes to the Ball (Menotti) 1995, 2001 Bartered Bride (Smetana) 1995, 2000, 2008 Calvary (Pasatieri) 1994 Carmen (Bizet) 1994, 2000 Cavalleria Rusticana (Mascagni) 1994, 2009 The Consul (Menotti) 1994, 2001 Elixir of Love (Donizetti) 1999 [Directed], 2004 Falstaff -

Luigi Dallapiccola's Il Prigioniero and Gian Carlo

LUIGI DALLAPICCOLA'S IL PRIGIONIERO AND GIAN CARLO MENOTTI'S THE CONSUL: A COMPARATIVE STUDY by JENNIFER GRAHAM STEPHENSON PAUL H. HOUGHTALING, COMMITTEE CHAIR SUSAN CURTIS FLEMING NIKOS A. PAPPAS STEPHEN V. PELES JONATHAN WHITAKER ELIZABETH AVERSA A DOCUMENT Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the School of Music in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2016 Copyright Jennifer Graham Stephenson 2016 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT As art reflects life, so too does it hold a mirror to the lives of the people who create it. The turbulent events of the first decades of the twentieth century, including two World Wars and the rise of Italian Fascism and German Nazism in the 1920s and 30s, affected millions of lives across several continents. This document explores the ways in which Luigi Dallapiccola (1904– 1973) and Gian Carlo Menotti (1911–2007) voice their reactions to these events in their operas, Il Prigioniero (1948) and The Consul (1950). Italian composer Luigi Dallapiccola spent twenty months in internment during the First World War, and would be forced on several occasions to go into hiding during the Second World War. His opposition to Mussolini and the Italian Fascists, coupled with his quasi–obsession with internment and freedom, led to his composition of three works of “protest music,” of which Il Prigioniero is the second. Il Prigioniero tells the story of a prisoner of the Inquisition, his attempt at escape and eventual capture. Italian-American composer Gian Carlo Menotti emigrated to the United States in 1928, at age seventeen, and spent a great much of his time traveling and working in various countries. -

A Study of Gian Carlo Menotti's Concerto for Violin and Orchestra

A STUDY OF GIAN CARLO MENOTTI’S CONCERTO FOR VIOLIN AND ORCHESTRA by LAURA ANNE TOMLIN (Under the Direction of Dorothea Link and Levon Ambartsumian) ABSTRACT Gian Carlo Menotti’s Concerto for Violin and Orchestra (1952), although written and premiered in the early 1950s, has been an unduly neglected work due to a number of circumstances, but one that has recently been gaining in popularity. The purpose of this document is to provide a comprehensive guide to the Violin Concerto in the hope that it will help capture the attention of those unaware of its existence and ultimately aide in the concerto’s acceptance into the violinist’s standard repertoire. The Violin Concerto’s historical context is examined in relationship to its compositional style and possible sources of inspiration, and to its neglect in the past and recent surge in popularity in the violin world. A formal and theoretical analysis of Menotti’s concerto, as well as a discussion of its technical challenges from the standpoint of the performer, will provide insight into its composition and interpretative issues. Despite its traditional form, Menotti’s Violin Concerto is an unusual piece in many respects, among which are its intriguing possible biographical components. Composed in 1952 for violinist Efrem Zimbalist, the work, on first hearing, can seem a bit disjointed with elements obviously derived from, or at the very least influenced by, other works. However, on closer examination of the work and of its intended performer, these elements appear to be intentional. For these reasons, in addition to its appeal simply as a composition, Menotti’s Violin Concerto is worthy of further study.