German Historical Institute London Bulletin Vol 40 (2018)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National World War I Museum 2008 Accessions to the Collections Doran L

NATIONAL WORLD WAR I MUSEUM 2008 ACCESSIONS TO THE COLLECTIONS DORAN L. CART, CURATOR JONATHAN CASEY, MUSEUM ARCHIVIST All accessions are donations unless otherwise noted. An accession is defined as something added to the permanent collections of the National World War I Museum. Each accession represents a separate “transaction” between donor (or seller) and the Museum. An accession can consist of one item or hundreds of items. Format = museum accession number + donor + brief description. For reasons of privacy, the city and state of the donor are not included here. For further information, contact [email protected] or [email protected] . ________________________________________________________________________ 2008.1 – Carl Shadd. • Machine rifle (Chauchat fusil-mitrailleur), French, M1915 CSRG (Chauchat- Sutter-Ribeyrolles and Gladiator); made at the Gladiator bicycle factory; serial number 138351; 8mm Lebel cartridge; bipod; canvas strap; flash hider (standard after January 1917); with half moon magazine; • Magazine carrier, French; wooden box with hinged lid, no straps; contains two half moon magazines; • Tool kit for the Chauchat, French; M1907; canvas and leather folding carrier; tools include: stuck case extractor, oil and kerosene cans, cleaning rod, metal screwdriver, tension spring tool, cleaning patch holder, Hotchkiss cartridge extractor; anti-aircraft firing sight. 2008.2 – Robert H. Rafferty. From the service of Cpl. John J. Rafferty, 1 Co 164th Depot Brigade: Notebook with class notes; • Christmas cards; • Photos; • Photo postcard. 2008.3 – Fred Perry. From the service of John M. Figgins USN, served aboard USS Utah : Diary; • Oversize photo of Utah ’s officers and crew on ship. 2008.4 – Leslie Ann Sutherland. From the service of 1 st Lieutenant George Vaughan Seibold, U.S. -

The Purpose of the First World War War Aims and Military Strategies Schriften Des Historischen Kollegs

The Purpose of the First World War War Aims and Military Strategies Schriften des Historischen Kollegs Herausgegeben von Andreas Wirsching Kolloquien 91 The Purpose of the First World War War Aims and Military Strategies Herausgegeben von Holger Afflerbach An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Schriften des Historischen Kollegs herausgegeben von Andreas Wirsching in Verbindung mit Georg Brun, Peter Funke, Karl-Heinz Hoffmann, Martin Jehne, Susanne Lepsius, Helmut Neuhaus, Frank Rexroth, Martin Schulze Wessel, Willibald Steinmetz und Gerrit Walther Das Historische Kolleg fördert im Bereich der historisch orientierten Wissenschaften Gelehrte, die sich durch herausragende Leistungen in Forschung und Lehre ausgewiesen haben. Es vergibt zu diesem Zweck jährlich bis zu drei Forschungsstipendien und zwei Förderstipendien sowie alle drei Jahre den „Preis des Historischen Kollegs“. Die Forschungsstipendien, deren Verleihung zugleich eine Auszeichnung für die bisherigen Leis- tungen darstellt, sollen den berufenen Wissenschaftlern während eines Kollegjahres die Möglich- keit bieten, frei von anderen Verpflichtungen eine größere Arbeit abzuschließen. Professor Dr. Hol- ger Afflerbach (Leeds/UK) war – zusammen mit Professor Dr. Paul Nolte (Berlin), Dr. Martina Steber (London/UK) und Juniorprofessor Simon Wendt (Frankfurt am Main) – Stipendiat des Historischen Kollegs im Kollegjahr 2012/2013. Den Obliegenheiten der Stipendiaten gemäß hat Holger Afflerbach aus seinem Arbeitsbereich ein Kolloquium zum Thema „Der Sinn des Krieges. Politische Ziele und militärische Instrumente der kriegführenden Parteien von 1914–1918“ vom 21. -

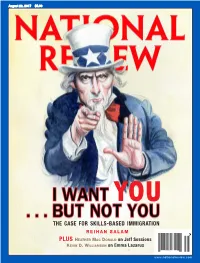

The Case for Skills-Based Immigration

20170828 subscribers_cover61404-postal.qxd 8/8/2017 4:46 PM Page 1 August 28, 2017 $5.99 YOU THE CASE FOR SKILLS-BASED IMMIGRATION REIHAN SALAM $5.99 35 PLUS HEATHER MAC DONALD on Jeff Sessions KEVIN D. WILLIAMSON on Emma Lazarus 0 73361 08155 1 www.nationalreview.com base_new_milliken-mar 22.qxd 8/8/2017 5:36 PM Page 1 Truth Matters …in private life and in the public square Educating for Citizenship e Republic Plato Nicomachean Ethics Politics Aristotle On Duties Cicero Treatise on Law St. omas Aquinas Second Treatise of Government John Locke e Federalist Papers Articles of Confederation Declaration of Independence e U.S. Constitution Democracy in America Alexis de Tocqueville e Lincoln–Douglas Debates Students read and discuss these texts and many more in a rigorous, 4-year Great Books program quinas A C s o a Thomas Aquinas College l m l e o g h e T Join us in supporting the 75% of students on nancial aid www.thomasaquinas.edu/uscitizen 1971 TOC-FINAL_QXP-1127940144.qxp 8/9/2017 2:37 PM Page 1 Contents AUGUST 28, 2017 | VOLUME LXIX, NO. 16 | www.nationalreview.com BOOKS, ARTS & MANNERS ON THE COVER Page 24 39 THE NEW MANICHAEANS Michael Knox Beran reviews The The Case for Skills-Based Once and Future Liberal: After Immigration Identity Politics, by Mark Lilla. 41 TWO KINDS OF PEOPLE The RAISE Act has the potential to Terry Teachout reviews Ernest Hemingway: A Biography, do a great deal of good. Instead of by Mary V. Dearborn, and Paradise sharpening our political and Lost: A Life of F. -

British Identity and the German Other William F

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2012 British identity and the German other William F. Bertolette Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Bertolette, William F., "British identity and the German other" (2012). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2726. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2726 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. BRITISH IDENTITY AND THE GERMAN OTHER A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by William F. Bertolette B.A., California State University at Hayward, 1975 M.A., Louisiana State University, 2004 May 2012 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to thank the LSU History Department for supporting the completion of this work. I also wish to express my gratitude for the instructive guidance of my thesis committee: Drs. David F. Lindenfeld, Victor L. Stater and Meredith Veldman. Dr. Veldman deserves a special thanks for her editorial insights -

"We Germans Fear God, and Nothing Else in the World!" Military Policy in Wilhelmine Germany, 1890-1914 Cavender Sutton East Tennessee State University

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2019 "We Germans Fear God, and Nothing Else in the World!" Military Policy in Wilhelmine Germany, 1890-1914 Cavender Sutton East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Sutton, Cavender, ""We Germans Fear God, and Nothing Else in the World!" Military Policy in Wilhelmine Germany, 1890-1914" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3571. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/3571 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “We Germans Fear God, and Nothing Else in the World!”: Military Policy in Wilhelmine Germany, 1890-1914 _________________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History _________________________ by Cavender Steven Sutton May 2019 _________________________ Stephen G. Fritz, Chair Henry J. Antkiewicz Brian J. Maxson Keywords: Imperial Germany, Military Policy, German Army, First World War ABSTRACT “We Germans Fear God, and Nothing Else in the World!”: Military Policy in Wilhelmine Germany, 1890-1914 by Cavender Steven Sutton Throughout the Second Reich’s short life, military affairs were synonymous with those of the state. -

The Cult of the Offensive and the Origins of the First World War Author(S): Stephen Van Evera Source: International Security, Vol

The Cult of the Offensive and the Origins of the First World War Author(s): Stephen Van Evera Source: International Security, Vol. 9, No. 1 (Summer, 1984), pp. 58-107 Published by: The MIT Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2538636 . Accessed: 18/04/2011 15:23 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at . http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=mitpress. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to International Security. http://www.jstor.org The Cult of the StephenVan Evera Offensiveand the Originsof the First WorldWar During the decades beforethe FirstWorld War a phenomenonwhich may be called a "cultof the offensive"swept throughEurope. -

"Typisch Deutsch

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by <intR>²Dok The Evolution of International Legal Scholarship in Germany during the Kaiserreich and the Weimarer Republik (1871–1933) By Anthony Carty A. Introduction and Issues of Methodology The dates 1871, 1918 and 1933 mark two constitutional periods in Germany, but they also mark the only period in history when Germany functioned as an independent State, apart from the Third Reich. During the period 1871 to 1933, an altogether free German intelligentsia and academia could reflect upon the legal significance of that independence. Since 1949 and even after 1989 Germany has seen itself as tied into a Western system of alliances, including the EU and the UN, where virtually all of its decisions are taken only in the closest consultation with numerous Allies and the intelligentsia is tied into debating within the parameters of an unquestionable Grundgesetz, or Basic Law. It will be the argument of this inevitably too short paper that the earlier period is not only significant in terms of German international law scholarship, but also stimulating for the general history of international law doctrine. The acute insecurity and unsettledness of Germany in this period provoked an appropriate intensity of international law reflection, although international lawyers rarely took central place in German intellectual culture. It is not clear why constitutional rupture of 1918–1919 may be so important because changes in government or constitution should not affect the understandings that a country has of international law. The State itself remains eternal. -

![GIM: Doing Business in Latin America 2015 ] Syllabus October 1, 2014](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3667/gim-doing-business-in-latin-america-2015-syllabus-october-1-2014-3023667.webp)

GIM: Doing Business in Latin America 2015 ] Syllabus October 1, 2014

Global Programs GIM: Doing Business in Latin America 2015 ] syllabus October 1, 2014 GIM: Doing Business in Latin America 2015 Winter 2015 - B – Spring 2015 - A Thursday, 6:30 – 9:30 PM Professor Daniel Lansberg-Rodríguez [email protected] Phone: 203-824-5739 Office hours: Jacobs Center, Room 5234, by appointment Global Programs GIM: Doing Business in Latin America 2015 ] syllabus October 1, 2014 GIM Program Objectives The GIM Program enables Kellogg students to: • Gain an understanding of the economic, political, social, and culture characteristics of a country or region outside the United States. • Learn about key business trends, industries, and sectors in a country or region outside the United States. • Conduct international business research on a topic of interest. • Further develop teamwork and leadership skills. Course Description and Objectives In theory, there is no difference between theory and practice. In practice, and certainly in Latin America, that difference can be pretty extreme. Despite being a diverse region, rich in resources and human capital, many Latin American countries routinely rank near the bottom of the World Bank’s Annual Ease of Doing Business Index. Even so, in our increasingly globalized world, a working knowledge of Latin American economics, business norms, and etiquette is of increasing importance given the importance of the region to energy markets, logistical chains, tourism and agriculture. Likewise, as domestic economies in countries like Brazil, Mexico and Colombia adapt to the changing retail and service needs of growing middle classes, many American companies have come to see Latin America not just as a potential target for investment, but for expansion as well. -

Graham Allison Dides Cy ’ T “Ash Carter’S Confirmation As Secretary of U R Defense Makes All of Us at the Belfer Center Proud,” a Said Center Director Graham Allison

Spring 2015 www.belfercenter.org Former Center Director Named Defense Secretary by Sharon Wilke shton B. Carter, a former director of the PHOTO AP ABelfer Center and professor at Harvard Ken- nedy School, was confirmed in February as the 25th secretary of defense of the United States. Carter served as deputy secretary of defense from 2011–13 and previously was under secretary of defense for acquisition, technology, and logistics. In earlier administrations, he served in both the Department of Defense and Department of State. “Ash’s expertise and dual background in science and policy make him uniquely qualified...” –Graham Allison dides cy ’ T “Ash Carter’s confirmation as secretary of u r defense makes all of us at the Belfer Center proud,” a said Center Director Graham Allison. “Ash’s h p expertise and dual background in science and T policy make him uniquely qualified for managing Afghan Assessment: U.S. Secretary of Defense Ashton B. Carter (left) walks with U.S. Army Gen. John the challenges posed by today’s unconstrained ene- Campbell upon arrival at Hamid Karzai International Airport in Kabul, Afghanistan on Feb. 21, 2015. mies and constrained resources. He also embodies a rare mix of academic depth and managerial savvy Center colleagues Steven E. Miller, Kurt Camp- with an even rarer ability to build a consensus for bell, and Charles Zraket worked around the clock See Inside: progress in Washington.” to produce the first comprehensive analysis of what Outside of government, Carter has spent much could happen to the Soviet Union’s nuclear weap- of his professional life at Harvard Kennedy School ons. -

Pan-Germanism

STUDIES AND DOCUMENTS ON THE WAR Pan-Germanism Its plans for German expansion in the World by CH. ANDLER Professor at the University of Paris Translated by J. S. Cette brochure est en vente à la LIBRAIRIE ARMAND COLIN 103, Boulevard Saint-Michel, PARIS, 5- au prix de 0 fr. 50 STUDIES AND DOCUMENTS ON THE WAR PUBLISHING COMMITTEE MM. ERNEST LAVISSE, of the « Académie française », President, CHARLES ANDLER, professor of German literature and language in the University of Paris. JOSEPH BÉDIER, professor at the « Collège de France ». HENRI BERGSON, of the « Académie française ». EMILE BOUTROUX, of the «Académie française ». ERNEST DENIS, professor of history in the University of Paris. EMILE DURKHEIM, professor in the University of Paris. JACQUES HADAMARD, of the «Académie des Sciences». GUSTAVE LANSON, professor of French literature in the University of Paris. CHARLES SEIGNOBOS, professor of history in the Uni versity of Paris. ANDRÉ WEISS, of the « Académie des Sciences morales et politiques ». All communications to be addressed to the Secretary of the Committee : M. EMILE DURKHEIM, 4, Avenue d'Orléans, PARIS, 14e. STUDIES AND DOCUMENTS ON THE WAR Pan-Germanism Its plans for German expansion in the World by CH, ANDLER Professor at the University of Paris Translated by J. $,. LIBRAIRIE ARMAND COLIN 103, Boulevard Saint-Michel, PARIS, .5' I 9 I 5 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE . • 3 I. — FIRST SYMPTOMS OF AGGRESSIVE PAN-GERMANISM 5 Symptoms of Pan-Germanism in the " Neuer Kurs " as far back as the accession of William II .5 Germany wishes to found a Customs Union as well as a military Union of the Central, European States ..... -

H2 Ventures and KPMG Are Excited to Present the Sixth Annual ‘Fintech100’ Report Which Compiles a List of the Year’S Leading Fintech Innovators from Around the World

2017 FINTECH100 Lean lobal Fntec Innovators 2018 2016 FINTECH100 FINTECH100 Lean lobal Lean lobal Fntec Innovators Fntec Innovators 1 | Fintech Innovators 2016 1 1 1 2018 Fintech100 Report 2017 Fintech100 Report 2016 Fintech100 Report Company #00 FINTECH 100 Leading Global “ Fintech Innovators Report 2015 Company Description At a Glance Tag Line Located Year Founded Key People The 50 Website Best Fintech Specialisation Staff Enabler or Disruptor Innovators Key Investors Ownership Size Report User Engagement $ $ $ $ $ The 100 Leading Fintech Innovators Report 2015 Fintech100 Report 2014 Fintech100 Report 2 About the List The Fintech100 is a collaborative effort between H2 Ventures and KPMG and analyses the fintech space globally. The Fintech100 comprises a ‘Top 50’ and an ‘Emerging 50’ and highlights those companies globally that are taking advantage of technology and driving disruption within the financial services industry. H2 Ventures H2 Ventures is one of the emerging thought leaders in fintech venture capital investment around the world. Founded by brothers Ben and Toby Heap, and based in Sydney, Australia, it invests alongside entrepreneurs and other investors in early stage fintech ventures. H2 Ventures is the manager of the H2 Accelerator - Australia’s leading fintech, data and artificial intelligence accelerator. Twitter @H2_Ventures LinkedIn H2 Ventures Facebook H2 Ventures KPMG Global Fintech The financial services industry is transforming with the emergence of innovative, new products, channels and business models. This wave of disruption is primarily driven by evolving customer expectations, digitalisation, as well as continued regulatory and cost pressures. KPMG is passionate about supporting our clients to successfully navigate this change, mitigating the threats and capitalising on the opportunities. -

Rassegna Stampa Estera

RASSEGNA STAMPA ESTERA 08 maggio 2020 INDICE PMI 08/05/2020 Financial Times 4 Start-up coaxes bank-shy Argentines to ditch cash STAMPA ESTERA 08/05/2020 New York Times International Edition 7 E.U. EXPECTS ITS WORST-EVER RECESSION 08/05/2020 New York Times International Edition 10 Factories are shut, but not this Corvette plant PRIME PAGINE 08/05/2020 Financial Times 13 PRIMA PAGINA PMI 1 articolo 08/05/2020 Pag. 6 La proprietà intellettuale è riconducibile alla fonte specificata in testa pagina. Il ritaglio stampa da intendersi per uso privato Technology. Digital finance Start-up coaxes bank-shy Argentines to ditch cash Coronavirus lockdown helps Tencent-backed Buenos Aires Challenger Ualà grow rapidly MICHAEL STOTT AND BENEDICI MANDER BUENOS AIRES Argentina is one of the world's toughest environments for investors, yet some of the biggest names in technology, including Tencent and SoftBank, have placed their first bets there on a fintech start-up that is reporting explosive growth amid the coronavirus lockdown. Launched in Buenos Aires in 2017 with the aim of persuading citizens in the largely cash-based economy to transact digitally, Ualà says that it has issued more than 1.9m debit cards and is signing up almost 0.5 per cent of Argentina's 44m population every month. "What we expected to happen over years is now happening over weeks," said Pierpaolo Barbieri, the 32-year-old Harvard-educated founder of Ualà. "Since the beginning of the quarantine 35 days ago, we have issued almost 140,000 cards, which is doublé our regular monthly issuance." Mr Barbieri moved his employees from Ualà's hipster warehouse-style offìces in the Argentine capital to work from home 10 days before the government imposed a lockdown in March.