Newsletter 26 Final.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hs161110dma Fishers Bridge Topsham Cycle

EEC/10/227/HQ Development Management Committee 24 November 2010 Town and Country Planning General Regulations 1992 - Regulation 3: Exeter City Council/East Devon District: Construction of a 28m Cycle/Footbridge over the River Clyst, located Downstream of Fisher's Bridge, Bridge Hill, Topsham, Exeter Applicant: Devon County Council Application No: DCC/3140/2010 Date Application received by County Council: 19 October 2010 Report of the Executive Director of Environment, Economy and Culture Please note that the following recommendation is subject to consideration and determination by the Committee before taking effect. Recommendation: It is recommended that, subject to no new material planning considerations being raised by Exeter City Council, and subject to confirmation from Natural England that there are likely to be no significant impacts on the Exe Estuary SPA/RAMSAR, [and that appropriate measures to mitigate against any adverse impact are put in place], the County Solicitor, in consultation with the Chairman, be authorised to grant planning permission in accordance with the planning conditions set out in Appendix II to this Report, plus any additional planning conditions, or amended conditions, that may be considered necessary in the light of discussions with Natural England and the RSPB. 1. Summary 1.1 This Report relates to a planning application for the proposed construction of a 28 metre cycle/footbridge over the River Clyst, downstream of Fisher's Bridge, Topsham. 1.2 It is considered that the key material planning considerations in the determination of the proposed development are the potential impact upon the nature conservation interests; the design of the bridge and possible landscape impacts; highway implications; and overall sustainability considerations. -

Grenville Research

David & Jenny Carter Nimrod Research Docton Court 2 Myrtle Street Appledore Bideford North Devon EX39 1PH www.nimrodresearch.co.uk [email protected] GRENVILLE RESEARCH This report has been produced to accompany the Historical Research and Statement of Significance Reports into Nos. 1 to 5 Bridge Street, Bideford. It should be noted however, that the connection with the GRENVILLE family has at present only been suggested in terms of Nos. 1, 2 and 3 Bridge Street. I am indebted to Andy Powell for locating many of the reference sources referred to below, and in providing valuable historical assistance to progress this research to its conclusions. In the main Statement of Significance Report, the history of the buildings was researched as far as possible in an attempt to assess their Heritage Value, with a view to the owners making a decision on the future of these historic Bideford properties. I hope that this will be of assistance in this respect. David Carter Contents: Executive Summary - - - - - - 2 Who were the GRENVILLE family? - - - - 3 The early GRENVILLEs in Bideford - - - - 12 Buckland Abbey - - - - - - - 17 Biography of Sir Richard GRENVILLE - - - - 18 The Birthplace of Sir Richard GRENVILLE - - - - 22 1585: Sir Richard GRENVILLE builds a new house at Bideford - 26 Where was GRENVILLE’s house on The Quay? - - - 29 The Overmantle - - - - - - 40 How extensive were the Bridge Street Manor Lands? - - 46 Coat of Arms - - - - - - - 51 The MEREDITH connection - - - - - 53 Conclusions - - - - - - - 58 Appendix Documents - - - - - - 60 Sources and Bibliography - - - - - 143 Wiltshire’s Nimrod Indexes founded in 1969 by Dr Barbara J Carter J.P., Ph.D., B.Sc., F.S.G. -

Bucktor, Double Waters, Devon Bucktor, Double Waters, Devon Double Waters, Buckland Monachorum, Yelverton, Tavistock 5 ½ Miles Princetown 6 Miles Plymouth 9 Miles

Bucktor, Double Waters, Devon Bucktor, Double Waters, Devon Double Waters, Buckland Monachorum, Yelverton, Tavistock 5 ½ miles Princetown 6 miles Plymouth 9 miles • Stunning Location • Stables and Outbuildings • Detached Annexe • Further Potential • 19 acres • Riparian Water Rights and Sporting Potential • Extensive accommodation Offers in excess of £725,000 SITUATION This is a truly stunning location and is the key to its enchanting beauty. Framed by sheep-speckled rolling moorland, Bucktor is approached along single track road across open moorland from the East. One could not hope for more privacy and seclusion, yet within 10 minutes drive of the pretty moorland village of Buckland Monachorum, on the western fringe of Dartmoor National Park. Further afield is the delightful and popular ancient market/stannary town of Tavistock, with an extensive range of facilities including fine independent schools. Follow the Tamar Estuary past Derriford Hospital and the maritime port of A truly stunning extended cottage with annexe and 19 acres, Plymouth will be found, with direct links to London and excellent facilities for sailing, including comprehensive marina provision and access to some of the fishing rights and lots of further potential. finest uncrowded waters in the country. The south coasts of Devon and Cornwall, with their beautiful estuaries, beaches and coastal walks, are within easy reach as well as the rugged coastline of North Cornwall. Dartmoor National Park, with its 368 square miles of spectacular scenery and rugged granite tors, is literally on the doorstep. This heather clad moorland, with deep wooded valleys and rushing streams, provides unlimited opportunities for walking, riding and fishing. -

Habitat Regulations Assessment Plymouth & SW Devon Joint Local Plan Contents

PLYMOUTH & SW DEVON JOINT PLAN V.07/02/18 Habitat Regulations Assessment Plymouth & SW Devon Joint Local Plan Contents 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 5 1.1 Preparation of a Local Plan ........................................................................................................... 5 1.2 Purpose of this Report .................................................................................................................. 7 2 Guidance and Approach to HRA ............................................................................................................. 8 3 Evidence Gathering .............................................................................................................................. 10 3.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 10 3.2 Impact Pathways ......................................................................................................................... 10 3.3 Determination of sites ................................................................................................................ 14 3.4 Blackstone Point SAC .................................................................................................................. 16 3.5 Culm Grasslands SAC .................................................................................................................. -

RIVER TAW CATCHMENT MANAGEMENT PLAN CONSULTATION REPORT En V Ir O N M E N T Ag E N C Y

NRA South West 28 RIVER TAW CATCHMENT MANAGEMENT PLAN CONSULTATION REPORT En v ir o n m e n t Ag e n c y NATIONAL LIBRARY & INFORMATION SERVICE HEAD OFFICE Rio House, Waterside Drive, Aztec West, Almondsbury, Bristol BS32 4UD NRA Copyright Waiver This report is intended to be used widely and may be quoted, copied or reproduced in any way, provided that the extracts are not quoted out of context and that due acknowledgement is given to the National Rivers Authority. Published December 1994 RIVER TAW CATCHMENT MANAGEMENT PLAN National Rivers Authority' Information Centre CONSULTATION REPORT Head Office Class No FOREWORD Accession No ... The National Rivers Authority has, since its formation in 19#9^bLUi ilu dueling lliL piULLii of catchment management. A major initiative is the commitment to produce Catchment Management Plans setting out the Authority’s vision for realising the potential of each local water environment. An important stage in the production of the plans is a period of public consultation. The NRA is keen to draw on the expertise and interest of the communities involved. Please comment, your views are important. A final plan will then be producted with an agreed action programme for the future protection and enhancement of this important catchment. The Information Centre Auth°»>y Watersidewl°"lRLvers Drive Aztec West Almondsbury Bristol BS12 4UD THE NATIONAL RIVERS AUTHORITY The NRA's mission and aims are as follows: " We will protect and improve the water environment by the effective management of water resources and by substantial reductions in pollution. We will aim to provide effective defence for people and property against flooding from rivers and the sea. -

5.30Pm Members of Cabinet View Directions

Agenda for Cabinet Wednesday 5 September 2018; 5.30pm Members of Cabinet East Devo n District Council Venue: Council Chamber, Knowle, Sidmouth, EX10 8HL Kno wle Sidmouth View directions Devon EX10 8HL Contact: Amanda Coombes, 01395 517543 DX 48705 Sidmouth (or group number 01395 517546) Tel: 01395 516551 Issued 24 August 2018 Fax: 01395 517507 www.eastdevon.gov.uk This meeting is being audio recorded by EDDC for subsequent publication on the Council’s website. Under the Openness of Local Government Bodies Regulations 2014, any members of the public are now allowed to take photographs, film and audio record the proceedings and report on all public meetings (including on social media). No prior notification is needed but it would be helpful if you could let the democratic services team know you plan to film or record so that any necessary arrangements can be made to provide reasonable facilities for you to report on meetings. This permission does not extend to private meetings or parts of meetings which are not open to the public. You should take all recording and photography equipment with you if a public meeting moves into a session which is not open to the public. If you are recording the meeting, you are asked to act in a reasonable manner and not disrupt the conduct of meetings for example by using intrusive lighting, flash photography or asking people to repeat statements for the benefit of the recording. You may not make an oral commentary during the meeting. The Chairman has the power to control public recording and/or reporting so it does not disrupt the meeting. -

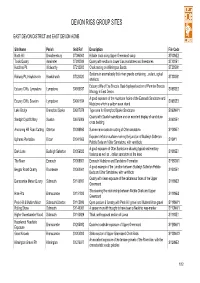

Devon Rigs Group Sites Table

DEVON RIGS GROUP SITES EAST DEVON DISTRICT and EAST DEVON AONB Site Name Parish Grid Ref Description File Code North Hill Broadhembury ST096063 Hillside track along Upper Greensand scarp ST00NE2 Tolcis Quarry Axminster ST280009 Quarry with section in Lower Lias mudstones and limestones ST20SE1 Hutchins Pit Widworthy ST212003 Chalk resting on Wilmington Sands ST20SW1 Sections in anomalously thick river gravels containing eolian ogical Railway Pit, Hawkchurch Hawkchurch ST326020 ST30SW1 artefacts Estuary cliffs of Exe Breccia. Best displayed section of Permian Breccia Estuary Cliffs, Lympstone Lympstone SX988837 SX98SE2 lithology in East Devon. A good exposure of the mudstone facies of the Exmouth Sandstone and Estuary Cliffs, Sowden Lympstone SX991834 SX98SE3 Mudstone which is seldom seen inland Lake Bridge Brampford Speke SX927978 Type area for Brampford Speke Sandstone SX99NW1 Quarry with Dawlish sandstone and an excellent display of sand dune Sandpit Clyst St.Mary Sowton SX975909 SX99SE1 cross bedding Anchoring Hill Road Cutting Otterton SY088860 Sunken-lane roadside cutting of Otter sandstone. SY08NE1 Exposed deflation surface marking the junction of Budleigh Salterton Uphams Plantation Bicton SY041866 SY0W1 Pebble Beds and Otter Sandstone, with ventifacts A good exposure of Otter Sandstone showing typical sedimentary Dark Lane Budleigh Salterton SY056823 SY08SE1 features as well as eolian sandstone at the base The Maer Exmouth SY008801 Exmouth Mudstone and Sandstone Formation SY08SW1 A good example of the junction between Budleigh -

Environmental Protection Final Draft Report

Environmental Protection Final Draft Report ANNUAL CLASSIFICATION OF RIVER WATER QUALITY 1992: NUMBERS OF SAMPLES EXCEEDING THE QUALITY STANDARD June 1993 FWS/93/012 Author: R J Broome Freshwater Scientist NRA C.V.M. Davies National Rivers Authority Environmental Protection Manager South West R egion ANNUAL CLASSIFICATION OF RIVER WATER QUALITY 1992: NUMBERS OF SAMPLES EXCEEDING TOE QUALITY STANDARD - FWS/93/012 This report shows the number of samples taken and the frequency with which individual determinand values failed to comply with National Water Council river classification standards, at routinely monitored river sites during the 1992 classification period. Compliance was assessed at all sites against the quality criterion for each determinand relevant to the River Water Quality Objective (RQO) of that site. The criterion are shown in Table 1. A dashed line in the schedule indicates no samples failed to comply. This report should be read in conjunction with Water Quality Technical note FWS/93/005, entitled: River Water Quality 1991, Classification by Determinand? where for each site the classification for each individual determinand is given, together with relevant statistics. The results are grouped in catchments for easy reference, commencing with the most south easterly catchments in the region and progressing sequentially around the coast to the most north easterly catchment. ENVIRONMENT AGENCY 110221i i i H i m NATIONAL RIVERS AUTHORITY - 80UTH WEST REGION 1992 RIVER WATER QUALITY CLASSIFICATION NUMBER OF SAMPLES (N) AND NUMBER -

Devon County Council Surface Water Management Plan Phase 1

Devon County Council Surface Water Management Plan Phase 1 – Strategic Assessment 28 February 2012 Rev: A Contents Glossary 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Introduction to a Surface Water Management Plan 1 1.2 Links to Sea and Main River Flooding 2 1.3 Methodology and Objectives 2 1.4 Outputs from Phase 1 4 1.5 Local Flood Risk Management Partnerships 5 2 Data Collation 6 2.1 Collation of Available Data 6 2.2 Observations from Data Review 8 3 Review of Other Flood Risk Management Studies 10 3.1 Introduction 10 3.2 National Surface Water Mapping Studies 10 3.3 Preliminary Flood Risk Assessment 12 3.4 Strategic Flood Risk Assessments 14 3.5 Catchment Flood Management Plans 19 3.6 Integrated Urban Drainage Studies 21 4 Local Flooding and Environmentally Sensitive Areas 22 4.1 Introduction 22 4.2 Legislative Context 22 4.3 Methodology 22 4.4 Results 24 5 Local Flooding and Heritage Assets 26 5.1 Introduction 26 6 Local Flooding and Impounded Water Bodies 28 7 Groundwater Flooding 29 7.1 Introduction 29 7.2 Recorded Incidents of Groundwater Flooding 29 7.3 Predicted Risk of Groundwater Flooding 30 7.4 Summary 31 8 Areas Identified for Development 34 8.1 The Importance of Planning in Flood Risk Management 34 8.2 Proposed Development in East Devon 35 8.3 Proposed Development in Exeter 37 8.4 Proposed Development in Mid Devon 38 8.5 Proposed Development in North Devon and Torridge 38 Devon SWMP – Phase 1 Strategic Assessment 8.6 Proposed Development in South Hams 39 8.7 Proposed Development in Teignbridge 39 8.8 Proposed Development in West Devon 41 9 Observations -

Black's Guide to Devonshire

$PI|c>y » ^ EXETt R : STOI Lundrvl.^ I y. fCamelford x Ho Town 24j Tfe<n i/ lisbeard-- 9 5 =553 v 'Suuiland,ntjuUffl " < t,,, w;, #j A~ 15 g -- - •$3*^:y&« . Pui l,i<fkl-W>«? uoi- "'"/;< errtland I . V. ',,, {BabburomheBay 109 f ^Torquaylll • 4 TorBa,, x L > \ * Vj I N DEX MAP TO ACCOMPANY BLACKS GriDE T'i c Q V\ kk&et, ii £FC Sote . 77f/? numbers after the names refer to the page in GuidcBook where die- description is to be found.. Hack Edinburgh. BEQUEST OF REV. CANON SCADDING. D. D. TORONTO. 1901. BLACK'S GUIDE TO DEVONSHIRE. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from University of Toronto http://www.archive.org/details/blacksguidetodevOOedin *&,* BLACK'S GUIDE TO DEVONSHIRE TENTH EDITION miti) fffaps an* Hlustrations ^ . P, EDINBURGH ADAM AND CHARLES BLACK 1879 CLUE INDEX TO THE CHIEF PLACES IN DEVONSHIRE. For General Index see Page 285. Axniinster, 160. Hfracombe, 152. Babbicombe, 109. Kent Hole, 113. Barnstaple, 209. Kingswear, 119. Berry Pomeroy, 269. Lydford, 226. Bideford, 147. Lynmouth, 155. Bridge-water, 277. Lynton, 156. Brixham, 115. Moreton Hampstead, 250. Buckfastleigh, 263. Xewton Abbot, 270. Bude Haven, 223. Okehampton, 203. Budleigh-Salterton, 170. Paignton, 114. Chudleigh, 268. Plymouth, 121. Cock's Tor, 248. Plympton, 143. Dartmoor, 242. Saltash, 142. Dartmouth, 117. Sidmouth, 99. Dart River, 116. Tamar, River, 273. ' Dawlish, 106. Taunton, 277. Devonport, 133. Tavistock, 230. Eddystone Lighthouse, 138. Tavy, 238. Exe, The, 190. Teignmouth, 107. Exeter, 173. Tiverton, 195. Exmoor Forest, 159. Torquay, 111. Exmouth, 101. Totnes, 260. Harewood House, 233. Ugbrooke, 10P. -

3.5 Horrabridge Commissioned a Survey and Desktop Examination of Records and Narrowed the Affected Area Down to Swathes Of

3.5 Horrabridge commissioned a survey and desktop examination of records and narrowed the affected area down to swathes of Part 3 The Core Strategy says the following land following the lines of the various about Horrabridge (section 3.5.4): mineral lodes. A number of properties A small town on the west of Dartmoor were found to be affected. Work to with its historic core centred on a Grade stabilise the areas affected has taken I listed bridge across the River Walkham. place to provide confidence and Its original industry was associated with reassurance to home owners. cloth mills and copper and tin mining. The town’s modern housing lies in sharp Improving the character and quality contrast to the modest buildings that of the built environment form the historic core. 3.5.3 Little survives of Horrabridge’s medieval Horrabridge’s vision looks to: roots today apart from the Grade I listed © sustain and improve the range bridge, fragments of the Chapel of John of local shops and services; the Baptist, and some typically medieval © resolve problems arising from property boundaries lying mostly to the historic mining activity; south of the river on the eastern side © improve the character and quality of the main street. Few early houses in of the built environment. the village survive in anything like their original form. The most striking change Sustaining and improving the range in the form of Horrabridge is the of local shops and services growth of 20th century urban housing 3.5.1 to the south of the river, which has Over the years there has been a significantly damaged historic field gradual reduction in the number of boundaries and disrupted the plan form shops and services operating in the of the settlement. -

CDWM Bulletin

Capital Development & Waste Management Bulletin w/c 24th November 2014 EDG DEVON COUNTY COUNCIL CYCLEWAY SCHEME WINS NATIONAL GREEN APPLE AWARD The Exe Estuary Trail’s River Clyst Bridge scheme has beaten some very prestigious and large projects across the UK to become National Green Champion during the International Green Apple Awards for Environmental Best Practice and Sustainable Development 2014. The bridge scheme was the brainchild of our Engineering Design Group who commissioned contractor Dyer and Butler to design and build the final structure that linked Exmouth to Topsham. Dyer & Butler submitted the project for the Green Apple Award and along with Clive Ryall, Senior Engineer in our Bridges Group attended the Award Ceremony in early November that was held on the Terrace Pavilion of the House of Commons. The team thought the scheme would be in with a chance of a commendation but winning the National Title was beyond their expectations with so much competition. The Project in context - The Exe Estuary is a Special Protection Area (SPA), Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) and has Important Bird Area (IBA) and Ramsar designations. Due to the exceptionally environmentally sensitive nature of the area, site activities were strictly controlled with construction only being allowed between March and September. As a result the scheme was built over a two year period with completion in November 2013 From Bowling Green Road in Topsham, the Trail runs through the RSPB Goosemoor Nature Reserve on 225 metres of boardwalk and elevated ramp, then passes over a new 114 metre span bridge to join the previously constructed sections of the Exe Estuary Trail to Exton and beyond.