Iguana 12.2 B&W Text

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chuckwalla Habitat in Nevada

Final Report 7 March 2003 Submitted to: Division of Wildlife, Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, State of Nevada STATUS OF DISTRIBUTION, POPULATIONS, AND HABITAT RELATIONSHIPS OF THE COMMON CHUCKWALLA, Sauromalus obesus, IN NEVADA Principal Investigator, Edmund D. Brodie, Jr., Department of Biology, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322-5305 (435)797-2485 Co-Principal Investigator, Thomas C. Edwards, Jr., Utah Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit and Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322-5210 (435)797-2509 Research Associate, Paul C. Ustach, Department of Biology, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322-5305 (435)797-2450 1 INTRODUCTION As a primary consumer of vegetation in the desert, the common chuckwalla, Sauromalus obesus (=ater; Hollingsworth, 1998), is capable of attaining high population density and biomass (Fitch et al., 1982). The 21 November 1991 Federal Register (Vol. 56, No. 225, pages 58804-58835) listed the status of chuckwalla populations in Nevada as a Category 2 candidate for protection. Large size, open habitat and tendency to perch in conspicuous places have rendered chuckwallas particularly vulnerable to commercial and non-commercial collecting (Fitch et al., 1982). Past field and laboratory studies of the common chuckwalla have revealed an animal with a life history shaped by the fluctuating but predictable desert climate (Johnson, 1965; Nagy, 1973; Berry, 1974; Case, 1976; Prieto and Ryan, 1978; Smits, 1985a; Abts, 1987; Tracy, 1999; and Kwiatkowski and Sullivan, 2002a, b). Life history traits such as annual reproductive frequency, adult survivorships, and population density have all varied, particular to the population of chuckwallas studied. Past studies are mostly from populations well within the interior of chuckwalla range in the Sonoran Desert. -

(2007) a Photographic Field Guide to the Reptiles and Amphibians Of

A Photographic Field Guide to the Reptiles and Amphibians of Dominica, West Indies Kristen Alexander Texas A&M University Dominica Study Abroad 2007 Dr. James Woolley Dr. Robert Wharton Abstract: A photographic reference is provided to the 21 reptiles and 4 amphibians reported from the island of Dominica. Descriptions and distribution data are provided for each species observed during this study. For those species that were not captured, a brief description compiled from various sources is included. Introduction: The island of Dominica is located in the Lesser Antilles and is one of the largest Eastern Caribbean islands at 45 km long and 16 km at its widest point (Malhotra and Thorpe, 1999). It is very mountainous which results in extremely varied distribution of habitats on the island ranging from elfin forest in the highest elevations, to rainforest in the mountains, to dry forest near the coast. The greatest density of reptiles is known to occur in these dry coastal areas (Evans and James, 1997). Dominica is home to 4 amphibian species and 21 (previously 20) reptile species. Five of these are endemic to the Lesser Antilles and 4 are endemic to the island of Dominica itself (Evans and James, 1997). The addition of Anolis cristatellus to species lists of Dominica has made many guides and species lists outdated. Evans and James (1997) provides a brief description of many of the species and their habitats, but this booklet is inadequate for easy, accurate identification. Previous student projects have documented the reptiles and amphibians of Dominica (Quick, 2001), but there is no good source for students to refer to for identification of these species. -

REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: TEIIDAE AMEIVA CORVINA Ameiva Corvina

REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: TEIIDAE AMEIVACORVINA Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. Shew, J.J., E.J. Censky, and R. Powell. 2002. Ameiva corvina. Ameiva corvina Cope Sombrero Island Ameiva Ameiva corvina Cope 186 1:3 12. Type locality, "island of Som- brero." Lectotype (designated by Censky and Paulson 1992), Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia (ANSP) 9 116, an adult male, collected by J.B. Hansen, date of collection not known (examined by EJC). See Remarks. CONTENT. No subspecies are recognized. DEFINITION. Ameiva corvina is a moderately sized mem- ber of the genus Ameiva (maximum SVL of males = 133 rnm, of females = 87 mm;Censky and Paulson 1992). Granular scales around the body number 139-156 (r = 147.7 f 2.4, N = 16), ventral scales 32-37 (7 = 34.1 + 0.3, N = 16), fourth toe subdigital lamellae 34-41 (F = 38.1 + 0.5, N = IS), fifteenth caudal verticil 29-38 (r = 33.3 0.6, N = 17), and femoral I I I + MAP. The arrow indicates Sombrero Island, the type locality and en- pores (both legs) 5M3(r = 57.3 0.8, N = 16)(Censky and + tire range of An~eivacorvina. Paulson 1992). See Remarks. Dorsal and lateral coloration is very dark brown to slate black and usually patternless (one individual, MCZ 6141, has a trace of a pattern with faded spots on the posterior third of the dor- sum and some balck blotches on the side of the neck). Brown color often is more distinct on the heads of males. The venter is very dark blue-gray. -

Predation on Ameiva Ameiva (Squamata: Teiidae) by Ardea Alba (Pelecaniformes: Ardeidae) in the Southwestern Brazilian Amazon

Herpetology Notes, volume 14: 1073-1075 (2021) (published online on 10 August 2021) Predation on Ameiva ameiva (Squamata: Teiidae) by Ardea alba (Pelecaniformes: Ardeidae) in the southwestern Brazilian Amazon Raul A. Pommer-Barbosa1,*, Alisson M. Albino2, Jessica F.T. Reis3, and Saara N. Fialho4 Lizards and frogs are eaten by a wide range of wetlands, being found mainly in lakes, wetlands, predators and are a food source for many bird species flooded areas, rivers, dams, mangroves, swamps, in neotropical forests (Poulin et al., 2001). However, and the shallow waters of salt lakes. It is a species predation events are poorly observed in nature and of diurnal feeding habits, but its activity peak occurs hardly documented (e.g., Malkmus, 2000; Aguiar and either at dawn or dusk. This characteristic changes Di-Bernardo, 2004; Silva et al., 2021). Such records in coastal environments, where its feeding habit is are certainly very rare for the teiid lizard Ameiva linked to the tides (McCrimmon et al., 2020). Its diet ameiva (Linnaeus, 1758) (Maffei et al., 2007). is varied and may include amphibians, snakes, insects, Found in most parts of Brazil, A. ameiva is commonly fish, aquatic larvae, mollusks, small crustaceans, small known as Amazon Racerunner or Giant Ameiva, and birds, small mammals, and lizards (Martínez-Vilalta, it has one of the widest geographical distributions 1992; Miranda and Collazo, 1997; Figueroa and among neotropical lizards. It occurs in open areas all Corales Stappung, 2003; Kushlan and Hancock 2005). over South America, the Galapagos Islands (Vanzolini We here report a predation event on the Ameiva ameiva et al., 1980), Panama, and several Caribbean islands by Ardea alba in the southwestern Brazilian Amazon. -

A Review of the Cnemidophorus Lemniscatus Group in Central America (Squamata: Teiidae), with Comments on Other Species in the Group

TERMS OF USE This pdf is provided by Magnolia Press for private/research use. Commercial sale or deposition in a public library or website is prohibited. Zootaxa 3722 (3): 301–316 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2013 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3722.3.1 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:4E9BA052-EEA9-4262-8DDA-E1145B9FA996 A review of the Cnemidophorus lemniscatus group in Central America (Squamata: Teiidae), with comments on other species in the group JAMES R. MCCRANIE1,3 & S. BLAIR HEDGES2 110770 SW 164th Street, Miami, Florida 33157-2933, USA. E-mail: [email protected] 2Department of Biology, 208 Mueller Laboratory, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania 16802-5301, USA. E-mail: [email protected] 3Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract We provide the results of a morphological and molecular study on the Honduran Bay Island and mainland populations of the Cnemidophorus lemniscatus complex for which we resurrect C. ruatanus comb. nov. as a full species. Morphological comparison of the Honduran populations to Cnemidophorus populations from Panama led to the conclusion that the Pan- amanian population represents an undescribed species named herein. In light of these new results, and considering past morphological studies of several South American populations of the C. lemniscatus group, we suggest that three other nominal forms of the group are best treated as valid species: C. espeuti (described as a full species, but subsequently treat- ed as a synonym of C. lemniscatus or a subspecies of C. -

Capacité Issue 4

CAPACITÉ Special Feature on Combating Invasive Alien Species CAPACITÉ – ISSUE 9 In this issue of Capacité, we turn our focus to invasive alien species (IAS). Several grants in the CEPF Caribbean portfolio are addressing this issue. And with good reason too. According to the CEPF Ecosystem Profile for the June 2014 Caribbean islands hotspot, the spread of invasive aliens is generally consid- ered the greatest threat to the native biodiversity of the region, especially to its endemic species, with invasive aliens recorded in a wide range of habitats throughout the hotspot. Inside this issue: An overview article by Island Conservation provides a useful context for un- Invasive Species on 2 Caribbean Islands: derstanding the threat of IAS in the Caribbean. Fauna & Flora International Extreme Threats but shares information about its work in the Eastern Caribbean along with useful Also Good News tips on using fixed-point photographs as a monitoring tool. From the Philadel- phia Zoo we learn about efforts to investigate the presence of the fungal dis- Making Pictures that 4 ease chytridiomicosis in amphibians in four key biodiversity areas in His- Speak A Thousand paniola. Words On the Case of the 6 We also feature the field-based work of the Environmental Awareness Group Highly Invasive in Antigua’s Offshore Islands, and of Island Conservation in association with Amphibian Chytrid Fun- gus in Hispaniola the Bahamas National Trust. These field-based efforts are complemented by initiatives by CAB International and Auckland Uniservices Ltd. to promote Connecting the Carib- 8 networking between and among IAS professionals and conservationists and bean KBAs via a Virtual build regional capacity to address IAS issues. -

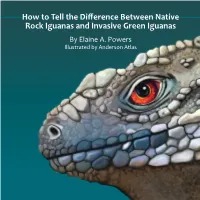

How to Tell the Difference Between Native Rock Iguanas and Invasive Green Iguanas by Elaine A

How to Tell the Difference Between Native Rock Iguanas and Invasive Green Iguanas By Elaine A. Powers Illustrated by Anderson Atlas Many of the islands in the Caribbean Sea, known as the West Rock Iguanas (Cyclura) Indies, have native iguanas. B Cuban Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila), Cuba They are called Rock Iguanas. C Sister Isles Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila caymanensis), Cayman Brac and Invasive Green Iguanas have been introduced on these islands and Little Cayman are a threat to the Rock Iguanas. They compete for food, territory D Grand Cayman Blue Iguana (Cyclura lewisi), Grand Cayman and nesting areas. E Jamaican Rock Iguana (Cyclura collei), Jamaica This booklet is designed to help you identify the native Rock F Turks & Caicos Rock Iguana (Cyclura carinata), Turks and Caicos. Iguanas from the invasive Greens. G Booby Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura carinata bartschi), Booby Cay, Bahamas H Andros Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura), Andros, Bahamas West Indies I Exuma Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura figginsi), Exuma Islands, Bahamas Exumas BAHAMAS J Allen’s Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura inornata), Exuma Islands, J Islands Bahamas M San Salvador Andros Island H Booby Cay K Anegada Iguana (Cyclura pinguis), British Virgin Islands Allens Cay White G I Cay Ricord’s Iguana (Cyclura ricordi), Hispaniola O F Turks & Caicos L CUBA NAcklins Island M San Salvador Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi), San Salvador, Bahamas Anegada HISPANIOLA CAYMAN ISLANDS K N Acklins Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi nuchalis), Acklins Islands, Bahamas B PUERTO RICO O White Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi cristata), Exuma Islands, Bahamas Grand Cayman D C JAMAICA BRITISH P Rhinoceros Iguana (Cyclura cornuta), Hispanola Cayman Brac & VIRGIN Little Cayman E L P Q Mona ISLANDS Q Mona Island Iguana (Cyclura stegnegeri), Mona Island, Puerto Rico Island 2 3 When you see an iguana, ask: What kind do I see? Do you see a big face scale, as round as can be? What species is that iguana in front of me? It’s below the ear, that’s where it will be. -

Filogeografia Do Lagarto Kentropyx Calcarata Spix 1825 (Reptilia: Teiidae) Na Amazônia Oriental

MUSEU PARAENSE EMÍLIO GOELDI UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO PARÁ PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM ZOOLOGIA CURSO DE MESTRADO EM ZOOLOGIA Filogeografia do lagarto Kentropyx calcarata Spix 1825 (Reptilia: Teiidae) na Amazônia Oriental ÁUREA AGUIAR CRONEMBERGER Belém-PA 2015 MUSEU PARAENSE EMÍLIO GOELDI UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO PARÁ PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM ZOOLOGIA CURSO DE MESTRADO EM ZOOLOGIA Filogeografia do lagarto Kentropyx calcarata Spix 1825 (Reptilia: Teiidae) na Amazônia Oriental ÁUREA AGUIAR CRONEMBERGER Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós- graduação em Zoologia, Curso de Mestrado do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi e Universidade Federal do Pará, como requisito para obtenção do grau de mestre em Zoologia. Orientadora: Dra. Teresa Cristina S. Ávila Pires Co-orientadora: Dra. Fernanda P. Werneck Belém-PA 2015 ÁUREA AGUIAR CRONEMBERGER Filogeografia do lagarto Kentropyx calcarata Spix 1825 (Reptilia: Teiidae) na Amazônia Oriental ___________________________________________ Dra. Teresa C. S. de Ávila-Pires, Orientadora Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi __________________________________________ Dra. Fernanda de Pinho Werneck, Coorientadora Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia ___________________________________________ Dra. Lilian Gimenes Giugliano (UNB) __________________________________________ Dr. Péricles Sena do Rego (UFPA) __________________________________________ Pedro Luiz Vieira del Peloso (UFPA) __________________________________________ Marcelo Coelho Miguel Gehara (UFRN) __________________________________________ Fernando -

Preliminary Checklist of Extant Endemic Species and Subspecies of the Windward Dutch Caribbean (St

Preliminary checklist of extant endemic species and subspecies of the windward Dutch Caribbean (St. Martin, St. Eustatius, Saba and the Saba Bank) Authors: O.G. Bos, P.A.J. Bakker, R.J.H.G. Henkens, J. A. de Freitas, A.O. Debrot Wageningen University & Research rapport C067/18 Preliminary checklist of extant endemic species and subspecies of the windward Dutch Caribbean (St. Martin, St. Eustatius, Saba and the Saba Bank) Authors: O.G. Bos1, P.A.J. Bakker2, R.J.H.G. Henkens3, J. A. de Freitas4, A.O. Debrot1 1. Wageningen Marine Research 2. Naturalis Biodiversity Center 3. Wageningen Environmental Research 4. Carmabi Publication date: 18 October 2018 This research project was carried out by Wageningen Marine Research at the request of and with funding from the Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality for the purposes of Policy Support Research Theme ‘Caribbean Netherlands' (project no. BO-43-021.04-012). Wageningen Marine Research Den Helder, October 2018 CONFIDENTIAL no Wageningen Marine Research report C067/18 Bos OG, Bakker PAJ, Henkens RJHG, De Freitas JA, Debrot AO (2018). Preliminary checklist of extant endemic species of St. Martin, St. Eustatius, Saba and Saba Bank. Wageningen, Wageningen Marine Research (University & Research centre), Wageningen Marine Research report C067/18 Keywords: endemic species, Caribbean, Saba, Saint Eustatius, Saint Marten, Saba Bank Cover photo: endemic Anolis schwartzi in de Quill crater, St Eustatius (photo: A.O. Debrot) Date: 18 th of October 2018 Client: Ministry of LNV Attn.: H. Haanstra PO Box 20401 2500 EK The Hague The Netherlands BAS code BO-43-021.04-012 (KD-2018-055) This report can be downloaded for free from https://doi.org/10.18174/460388 Wageningen Marine Research provides no printed copies of reports Wageningen Marine Research is ISO 9001:2008 certified. -

Bibliography and Scientific Name Index to Amphibians

lb BIBLIOGRAPHY AND SCIENTIFIC NAME INDEX TO AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES IN THE PUBLICATIONS OF THE BIOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF WASHINGTON BULLETIN 1-8, 1918-1988 AND PROCEEDINGS 1-100, 1882-1987 fi pp ERNEST A. LINER Houma, Louisiana SMITHSONIAN HERPETOLOGICAL INFORMATION SERVICE NO. 92 1992 SMITHSONIAN HERPETOLOGICAL INFORMATION SERVICE The SHIS series publishes and distributes translations, bibliographies, indices, and similar items judged useful to individuals interested in the biology of amphibians and reptiles, but unlikely to be published in the normal technical journals. Single copies are distributed free to interested individuals. Libraries, herpetological associations, and research laboratories are invited to exchange their publications with the Division of Amphibians and Reptiles. We wish to encourage individuals to share their bibliographies, translations, etc. with other herpetologists through the SHIS series. If you have such items please contact George Zug for instructions on preparation and submission. Contributors receive 50 free copies. Please address all requests for copies and inquiries to George Zug, Division of Amphibians and Reptiles, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC 20560 USA. Please include a self-addressed mailing label with requests. INTRODUCTION The present alphabetical listing by author (s) covers all papers bearing on herpetology that have appeared in Volume 1-100, 1882-1987, of the Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington and the four numbers of the Bulletin series concerning reference to amphibians and reptiles. From Volume 1 through 82 (in part) , the articles were issued as separates with only the volume number, page numbers and year printed on each. Articles in Volume 82 (in part) through 89 were issued with volume number, article number, page numbers and year. -

The Bisexual Brain: Sex Behavior Differences and Sex Differences in Parthenogenetic and Sexual Lizards

BRAIN RESEARCH ELSEVIER Brain Research 663 (1994) 163-167 Short communication The bisexual brain: sex behavior differences and sex differences in parthenogenetic and sexual lizards Matthew S. Rand *, David Crews Institute of Reproductive Biology, Department of Zoology, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX 78712, USA Accepted 2 August 1994 Abstract The parthenogenetic lizard Cnemidophorus uniparens alternates in the display of male-like and female-like sexual behavior, providing a unique opportunity for determining the neuronal circuits subserving gender-typical sexual behavior within a single sex. Here we report a 6-fold greater [14C]2-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose uptake in the medial preoptic area of C. uniparens displaying male-like behavior in comparison with C. uniparens displaying female-like receptivity. The ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus showed greater 2DG accumulation in receptive C. uniparens than in courting C. uniparens. When a related sexual species (C. inornatus) was compared to the unisexual species, the anterior hypothalamus in C. inornatus males exhibited significantly greater activity. Keywords: 2-Deoxyglucose; Anterior hypothalamus; Medial preoptic area; Reptile; Ventromedial hypothalamus Female-typical and male-typical sex behavior are C. inornatus [7,17]. The aims of this study were to known to be integrated by specific hypothalamic nuclei determine: (1) if specific regions in the brains of in the vertebrate brain [6,18,22]. The ventromedial parthenogenetic and gonochoristic whiptail lizards ex- nucleus of the hypothalamus (VMH) and the medial hibit sexually dimorphic metabolic activity, as mea- preoptic area (mPOA) are involved in sexual receptiv- sured by the accumulation of [14C]2-fluoro-2-de- ity in females and both the mPOA and anterior hy- oxyglucose (2DG) in the brain during mating behavior, pothalamus (AH) play an important role in the regula- and (2) if these dimorphisms complement previous tion of copulatory behavior in males [6,18,19,22]. -

First Report of Cannibalism in The

WWW.IRCF.ORG/REPTILESANDAMPHIBIANSJOURNALTABLE OF CONTENTS IRCF REPTILES & IRCFAMPHIBIANS REPTILES • VOL 15,& NAMPHIBIANSO 4 • DEC 2008 •189 21(4):136–137 • DEC 2014 IRCF REPTILES & AMPHIBIANS CONSERVATION AND NATURAL HISTORY TABLE OF CONTENTS FEATURE ARTICLES First. Chasing Bullsnakes Report (Pituophis catenifer sayi) in Wisconsin:of Cannibalism in the On the Road to Understanding the Ecology and Conservation of the Midwest’s Giant Serpent ...................... Joshua M. Kapfer 190 . The Shared History of Treeboas (Corallus grenadensis) and Humans on Grenada: Saba AnoleA Hypothetical Excursion ( ............................................................................................................................Anolis sabanus), withRobert W. Hendersona Review 198 ofRESEARCH Cannibalism ARTICLES in West Indian Anoles . The Texas Horned Lizard in Central and Western Texas ....................... Emily Henry, Jason Brewer, Krista Mougey, and Gad Perry 204 . The Knight Anole (Anolis equestris) in Florida 1 2 .............................................Brian J. RobertCamposano, Powell Kenneth L. andKrysko, Adam Kevin M. Watkins Enge, Ellen M. Donlan, and Michael Granatosky 212 1Department of Biology, Avila University, Kansas City, Missouri 64145, USA ([email protected]) CONSERVATION ALERT 2Chizzilala Video Productions, Saba ([email protected]) . World’s Mammals in Crisis ............................................................................................................................................................