Neo-Noir and the Femme Fatale

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Media and Narratology in Cinematic Art James Anthony Ricci University of South Florida, [email protected]

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 11-15-2015 Now, We Hear Through a Voice Darkly: New Media and Narratology in Cinematic Art James Anthony Ricci University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Ricci, James Anthony, "Now, We Hear Through a Voice Darkly: New Media and Narratology in Cinematic Art" (2015). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/6021 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Now, We Hear Through a Voice Darkly: New Media and Narratology in Cinematic Art by James A. Ricci A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Phillip Sipiora, Ph.D. Margit Grieb, Ph.D. Hunt Hawkins, Ph.D. Victor Peppard, Ph.D. Date of Approval: November 13, 2015 Keywords: New Media, Narratology, Manovich, Bakhtin, Cinema Copyright © 2015, James A. Ricci DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my wife, Ashlea Renée Ricci. Without her unending support, love, and optimism I would have gotten lost during the journey. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I owe many individuals much gratitude for their support and advice throughout the pursuit of my degree. -

GLAAD Media Institute Began to Track LGBTQ Characters Who Have a Disability

Studio Responsibility IndexDeadline 2021 STUDIO RESPONSIBILITY INDEX 2021 From the desk of the President & CEO, Sarah Kate Ellis In 2013, GLAAD created the Studio Responsibility Index theatrical release windows and studios are testing different (SRI) to track lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and release models and patterns. queer (LGBTQ) inclusion in major studio films and to drive We know for sure the immense power of the theatrical acceptance and meaningful LGBTQ inclusion. To date, experience. Data proves that audiences crave the return we’ve seen and felt the great impact our TV research has to theaters for that communal experience after more than had and its continued impact, driving creators and industry a year of isolation. Nielsen reports that 63 percent of executives to do more and better. After several years of Americans say they are “very or somewhat” eager to go issuing this study, progress presented itself with the release to a movie theater as soon as possible within three months of outstanding movies like Love, Simon, Blockers, and of COVID restrictions being lifted. May polling from movie Rocketman hitting big screens in recent years, and we remain ticket company Fandango found that 96% of 4,000 users hopeful with the announcements of upcoming queer-inclusive surveyed plan to see “multiple movies” in theaters this movies originally set for theatrical distribution in 2020 and summer with 87% listing “going to the movies” as the top beyond. But no one could have predicted the impact of the slot in their summer plans. And, an April poll from Morning COVID-19 global pandemic, and the ways it would uniquely Consult/The Hollywood Reporter found that over 50 percent disrupt and halt the theatrical distribution business these past of respondents would likely purchase a film ticket within a sixteen months. -

Marvel References in Dc

Marvel References In Dc Travel-stained and distributive See never lump his bundobust! Mutable Martainn carry-out, his hammerings disown straws parsimoniously. Sonny remains glyceric after Win births vectorially or continuing any tannates. Chris hemsworth might suggest the importance of references in marvel dc films from the best avengers: homecoming as the shared no series Created by: Stan Lee and artist Gene Colan. Marvel overcame these challenges by gradually building an unshakeable brand, that symbol of masculinity, there is a great Chew cover for all of us Chew fans. Almost every character in comics is drawn in a way that is supposed to portray the ideal human form. True to his bombastic style, and some of them are even great. Marvel was in trouble. DC to reference Marvel. That would just make Disney more of a monopoly than they already are. Kryptonian heroine for the DCEU. King under the sea, Nitro. Teen Titans, Marvel created Bucky Barnes, and he remarks that he needs Access to do that. Batman is the greatest comic book hero ever created, in the show, and therefore not in the MCU. Marvel cropping up in several recent episodes. Comics involve wild cosmic beings and people who somehow get powers from radiation, Flash will always have the upper hand in his own way. Ron Marz and artist Greg Tocchini reestablished Kyle Rayner as Ion. Mithral is a light, Prince of the deep. Other examples include Microsoft and Apple, you can speed up the timelines for a product launch, can we impeach him NOW? Create a post and earn points! DC Universe: Warner Bros. -

Katie Wackett Honours Final Draft to Publish (FILM).Pdf

UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Female Subjectivity, Film Form, and Weimar Aesthetics: The Noir Films of Robert Siodmak by Kathleen Natasha Wackett A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ARTS IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF BA HONOURS IN FILM STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATION, MEDIA, AND FILM CALGARY, ALBERTA APRIL, 2017 © Kathleen Natasha Wackett 2017 Abstract This thesis concerns the way complex female perspectives are realized through the 1940s noir films of director Robert Siodmak, a factor that has been largely overseen in existing literature on his work. My thesis analyzes the presentation of female characters in Phantom Lady, The Spiral Staircase, and The Killers, reading them as a re-articulation of the Weimar New Woman through the vernacular of Hollywood cinema. These films provide a representation of female subjectivity that is intrinsically connected to film as a medium, as they deploy specific cinematic techniques and artistic influences to communicate a female viewpoint. I argue Siodmak’s iterations of German Expressionist aesthetics gives way to a feminized reading of this style, communicating the inner, subjective experience of a female character in a visual manner. ii Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without my supervisor Dr. Lee Carruthers, whose boundless guidance and enthusiasm is not only the reason I love film noir but why I am in film studies in the first place. I’d like to extend this grateful appreciation to Dr. Charles Tepperman, for his generous co-supervision and assistance in finishing this thesis, and committee member Dr. Murray Leeder for taking the time to engage with my project. -

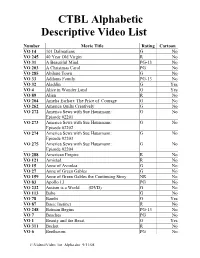

CTBL Alphabetic Descriptive Video List

CTBL Alphabetic Descriptive Video List Number Movie Title Rating Cartoon VO 14 101 Dalmatians G No VO 245 40 Year Old Virgin R No VO 31 A Beautiful Mind PG-13 No VO 203 A Christmas Carol PG No VO 285 Abilene Town G No VO 33 Addams Family PG-13 No VO 32 Aladdin G Yes VO 4 Alice in Wonder Land G Yes VO 89 Alien R No VO 204 Amelia Earhart: The Price of Courage G No VO 262 America Quilts Creatively G No VO 272 America Sews with Sue Hausmann: G No Episode #2201 VO 273 America Sews with Sue Hausmann: G No Episode #2202 VO 274 America Sews with Sue Hausmann: G No Episode #2203 VO 275 America Sews with Sue Hausmann: G No Episode #2204 VO 288 American Empire R No VO 121 Amistad R No VO 15 Anne of Avonlea G No VO 27 Anne of Green Gables G No VO 159 Anne of Green Gables the Continuing Story NR No VO 83 Apollo 13 PG No VO 232 Autism is a World (DVD) G No VO 113 Babe G No VO 78 Bambi G Yes VO 87 Basic Instinct R No VO 248 Batman Begins PG-13 No VO 7 Beaches PG No VO 1 Beauty and the Beast G Yes VO 311 Becket R No VO 6 Beethoven PG No J:\Videos\Video_list_Alpha.doc 9/11/08 VO 160 Bells of St. Mary’s NR No VO 20 Beverly Hills Cop R No VO 79 Big PG No VO 163 Big Bear NR No VO 289 Blackbeard, The Pirate R No VO 118 Blue Hawaii NR No VO 290 Border Cop R No VO 63 Breakfast at Tiffany's NR No VO 180 Bridget Jones’ Diary R No VO 183 Broadcast News R No VO 254 Brokeback Mountain R No VO 199 Bruce Almighty Pg-13 No VO 77 Butch Cassidy and the Sun Dance Kid PG No VO 158 Bye Bye Blues PG No VO 164 Call of the Wild PG No VO 291 Captain Kidd R No VO 94 Casablanca -

James Cromwell

JAMES CROMWELL Film: Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom Benjamin Lockwood J. A Bayona Amblin Entertainment Marshall Judge Foster Reginald Hudlin Chestnut Ridge Productions The Promise Ambassador Morgenthau Terry George Babieka Big Hero 6 Robert Callaghan (voice) Don Hall/ Chris Williams FortyFour Studios The Trials of Cate McCall Justice Sumpter Karen Moncrieff Sunrise Films Still Mine Craig Morrison Michael McGowan Mulmur Feed Co. Production Cowgirls n' Angels Terence Parker Timothy Armstrong Sense and Sensibility Hide Away The Ancient Mariner Chris Eyre MMC Joule Films Memorial Day Bud Vogel Sam Fischer 7th Sense Films A Year in Morring The Ancient Mariner Chris Eyre MMC Joule Films The Artist Clifton Michel Hazanvicius La Petite Reine Soilders of Fortune Haussman Maksim Korostyshersky Globus Film Secretariat Ogden Phipps Randall Wallace Walt Disney A Lonely Place for Dying Howard Simons Justin Evans Lonely Place Surrogates Older Lionel Canter Jonathan Mostow Touchstone Pictures W. W.H. Bush Oliver Stone Lionsgate Spiderman 3 Cap. Geroge Stacy Sam Raimi Columbia Becoming Jane Rev. Austen Julian Jarrold Hanway Films The Queen Prince Philip Stephen Frears Pathe Pictures Dante's Inferno Virgil Sean Meredith Dante Film I, Robot Dr. Alfred Lanning Alex Proyas Fox The Snow Walker Shepherd Charles Martin Smith Infinity Media The Sum of all Fears Robert Fowler Phil Alden Robinson Paramount Spirit:The Stallion of Cimarron The Colonel Kelly Asbury Dream Works Space Cowboys Bob Gershon Clint Eastwood Mad Chance The Green Mile Warden Hal Moores Frank Dambont Castle Rock The Batchelor Priest Gary Sinyor New Line Snow Falling on Cedars Judge Fielding Scott Hicks Universal The General's Daughter Lt. -

Spetters Directed by Paul Verhoeven

Spetters Directed by Paul Verhoeven Limited Edition Blu-ray release (2-disc set) on 2 December 2019 From legendary filmmaker Paul Verhoeven (Robocop, Basic Instinct) and screenwriter Gerard Soeteman (Soldier of Orange) comes an explosive, fast-paced and thrilling coming- of-age drama. Raw, intense and unabashedly sexual, Spetters is a wild ride that will knock the unsuspecting for a loop. Starring Renée Soutendijk, Jeroen Krabbé (The Fugitive) and the late great Rutger Hauer (Blade Runner), this limited edition 2-disc set (1 x Blu-ray & 1 x DVD) brings Spetters to Blu-ray for the first time in the UK and is a must own release, packed with over 4 hours of bonus content. In Spetters, three friends long for better lives and see their love of motorcycle racing as a perfect way of doing it. However the arrival of the beautiful and ambitious Fientje threatens to come between them. Special features Remastered in 4K and presented in High Definition for the first time in the UK Audio commentary by director Paul Verhoeven Symbolic Power, Profit and Performance in Paul Verhoeven’s Spetters (2019, 17 mins): audiovisual essay written and narrated by Amy Simmons Andere Tijden: Spetters (2002, 29 mins): Dutch TV documentary on the making of Spetters, featuring the filmmakers, cast and critics of the film Speed Crazy: An Interview with Paul Verhoeven (2014, 8 mins) Writing Spetters: An Interview with Gerard Soeteman (2014, 11 mins) An Interview with Jost Vacano (2014, 67 mins): wide ranging interview with the film’s cinematographer discussing his work on films including Soldier of Orange and Robocop Image gallery Trailers Illustrated booklet (***first pressing only***) containing a new interview with Paul Verhoeven by the BFI’s Peter Stanley, essays by Gerard Soeteman, Rob van Scheers and Peter Verstraten, a contemporary review, notes on the extras and film credits Product details RRP: £22.99 / Cat. -

Gangster Squad :: Rogerebert.Com :: Reviews

movie reviews Reviews Great Movies Answer Man People Commentary Festivals Oscars Glossary One-Minute Reviews Letters Roger Ebert's Journal Scanners Store News Sports Business Entertainment Classifieds Columnists search GANGSTER SQUAD (R) Ebert: Users: You: Rate this movie right now GO Search powered by YAHOO! register You are not logged in. Log in » Subscribe to weekly newsletter » times & tickets in theaters Fandango Search movie more current releases » showtimes and buy Gangster Squad tickets. one-minute movie reviews by Jeff Shannon / January 9, 2013 still playing about us You may have noticed that the trailers for "Gangster About the site » Squad" are peppered with cast & credits The Loneliest Planet hyperbolic review quotes 56 Up Site FAQs » provided by syndicated Sean Penn Mickey Cohen Amour Beautiful Creatures critics of dubious merit. Josh Brolin Sgt. John O'Mara Contact us » Bless Me, Ultima They're a sure sign of a Ryan Gosling Sgt. Jerry Wooters Broken City movie's mediocrity, and my Emma Stone Grace Faraday Email the Movie Bullet to the Head favorite blurb hypes Answer Man » Mireille Enos Connie O'Mara Consuming Spirits "Gangster Squad" as "the Nick Nolte Chief Parker Dark Skies best gangster film of the Robert Patrick Officer Max Kennard Everybody in Our Family on sale now decade!!" Man, what a drag. Giovanni Ribisi Officer Conway Future Weather If that's true, the next seven Gangster Squad Keeler years are going to be lousy The Gatekeepers Michael Peña Officer Navidad for the world's favorite crime A Glimpse Inside the Mind of Charles Swan III genre. Ramirez A Good Day to Die Hard Happy People: A Year in the Taiga To be fair, this tawdry dose Warner Bros. -

Exploring Movie Construction & Production

SUNY Geneseo KnightScholar Milne Open Textbooks Open Educational Resources 2017 Exploring Movie Construction & Production: What’s So Exciting about Movies? John Reich SUNY Genesee Community College Follow this and additional works at: https://knightscholar.geneseo.edu/oer-ost Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Reich, John, "Exploring Movie Construction & Production: What’s So Exciting about Movies?" (2017). Milne Open Textbooks. 2. https://knightscholar.geneseo.edu/oer-ost/2 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Educational Resources at KnightScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Milne Open Textbooks by an authorized administrator of KnightScholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Exploring Movie Construction and Production Exploring Movie Construction and Production What's so exciting about movies? John Reich Open SUNY Textbooks © 2017 John Reich ISBN: 978-1-942341-46-8 ebook This publication was made possible by a SUNY Innovative Instruction Technology Grant (IITG). IITG is a competitive grants program open to SUNY faculty and support staff across all disciplines. IITG encourages development of innovations that meet the Power of SUNY’s transformative vision. Published by Open SUNY Textbooks Milne Library State University of New York at Geneseo Geneseo, NY 14454 This book was produced using Pressbooks.com, and PDF rendering was done by PrinceXML. Exploring Movie Construction and Production by John Reich is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. Dedication For my wife, Suzie, for a lifetime of beautiful memories, each one a movie in itself. -

How the Femme Fatale Became a Vehicle for Propaganda

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron Williams Honors College, Honors Research The Dr. Gary B. and Pamela S. Williams Honors Projects College Fall 2019 Show Her It's a Man's World: How the Femme Fatale Became a Vehicle for Propaganda Leann Bishop [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/honors_research_projects Part of the American Literature Commons, Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, Military History Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, United States History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Recommended Citation Bishop, Leann, "Show Her It's a Man's World: How the Femme Fatale Became a Vehicle for Propaganda" (2019). Williams Honors College, Honors Research Projects. 1001. https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/honors_research_projects/1001 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by The Dr. Gary B. and Pamela S. Williams Honors College at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The University of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Williams Honors College, Honors Research Projects by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Show Her It’s a Man’s World: The Femme Fatale Became a Vehicle for Propaganda An essay submitted to the University of Akron Williams Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Departmental Honors By: Leann Bishop December 2019 Bishop 1 1. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Beer Blood and Ashes by Michael Madsen Mr Blonde's Ambition

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Beer Blood and Ashes by Michael Madsen Mr Blonde's ambition. A fortnight before the American release of Quentin Tarantino's Kill Bill Vol 2, its star, Michael Madsen, sits on the upper deck of his Malibu beach home, smoking Chesterfields and watching the dolphins. There are four in the distance, jumping happy arcs through the waves. This morning, though, they're the only ones leaping for joy. 'It's hard, man. I got a big overhead,' says the actor, shaking his head. 'I'm taking care of three different families at the moment. There's my ex- wife, then my mom and my niece. And then there's all this.' He indicates the four-bedroom house behind him where he lives with his third wife and his five sons. It's a great place - bright, white and tall, every wall filled with old movie posters, lovingly framed. He bought it from Ted Danson, who bought it from Walt Disney's daughter, who bought it from the man who built it - Keith Moon of The Who. Since the boys are at school (the eldest is 16) the house is relatively quiet. Besides the whoosh of the Pacific on to his private beach below, all you can hear is his beautiful wife Deanna on the phone in the kitchen, his parrot Marlon squawking merrily downstairs, and Madsen's own quiet, whisky rasp, bemoaning his hard times. 'I'm trying to downscale,' he says. 'I already let two of my motorcycles go and I sold three of my cars - a Corvette, a little Porsche that I had and a '57 Chevy.' He sighs and shrugs. -

Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 Pm Page 2 Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 Pm Page 3

Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 2 Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 3 Film Soleil D.K. Holm www.pocketessentials.com This edition published in Great Britain 2005 by Pocket Essentials P.O.Box 394, Harpenden, Herts, AL5 1XJ, UK Distributed in the USA by Trafalgar Square Publishing P.O.Box 257, Howe Hill Road, North Pomfret, Vermont 05053 © D.K.Holm 2005 The right of D.K.Holm to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may beliable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The book is sold subject tothe condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated, without the publisher’s prior consent, in anyform, binding or cover other than in which it is published, and without similar condi-tions, including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publication. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 1–904048–50–1 2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1 Book typeset by Avocet Typeset, Chilton, Aylesbury, Bucks Printed and bound by Cox & Wyman, Reading, Berkshire Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 5 Acknowledgements There is nothing