Self-Publishing and Collection Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Media Kit

2019 MEDIA KIT Introducing thousands of readers to up and coming authors Creating unique platforms for writers, publishers and brands to grow fans and drive sales www.BookTrib.com | [email protected] BOOKTRIB 2019 MEDIA KIT WELCOME TO BOOKTRIB.COM BookTrib.com is a discovery zone for readers who love books and a marketing engine for authors and publishers. BookTrib.com brings discerning readers and rising authors closer together – and in a big way, with more than 70,000 unique monthly website visitors and close to 50,000 views on social media. BookTrib.com is produced by Meryl Moss Media, a leading literary publicity and marketing firm which for more than 25 years has helped authors reach their readers through media exposure, speaking engagements and marketing initiatives. Through publicity campaigns that are seamless, newsworthy and on target, Meryl Moss Media has surpassed the competition because of its experience and skillful agility creating smart and powerful mediagenic stories and pitches. When traditional media outlets started reducing their coverage of books and authors, Meryl Moss put a stake in the ground and founded BookTrib. com to keep books alive and relevant, featuring under-the-radar authors who deserved to be noticed and who readers would enjoy discovering, as well as the hot new books from well-known authors. The site features in-depth interviews, reviews, video discussions, podcasts, even authors writing about other authors. BookTrib.com is a Meryl Moss haven for anyone searching for his or her next read or simply addicted to all things book-related. Debut, emerging and established authors, as well as book publishers and other brands associated with the book industry, come to BookTrib.com for help generating awareness, increasing followers, and ultimately selling more books. -

Collection Development Policy Statement Rare Books Collection Subject Specialist Responsible

Collection Development Policy Statement Rare Books Collection Subject Specialist responsible: Doug McElrath, 301‐405‐9210, [email protected] I. Purpose The Rare Books Collection in the University of Maryland Libraries preserves physical evidence of the most successful format for recording and disseminating human knowledge: the printed codex. From the invention of printing with movable type in Asia to its widespread adoption and explosive growth in 15th century Europe, the printed book in all its forms has had an inestimable impact on the way information has been organized, spread, and consumed. The invention of printing is one of the critical technological advances that made possible the modern world. At the University of Maryland, the Rare Books Collection serves multiple purposes: As a teaching collection that preserves physical examples of the way the book has evolved over the centuries, from a hand‐crafted artifact to a mass‐produced consumable. As a research collection for targeted concentrations of printed text supporting scholarly investigation (see collection scope below). As an historical repository for outstanding examples of human accomplishment as preserved in printed formats, including seminal works in the arts, humanities, social sciences, physical and biological sciences. As a research repository for noteworthy examples of the art and craft of the book: typography, bindings, paper making, illustration, etc. As a secure storehouse for works that because of their scarcity, fragility, age, ephemerality, provenance, controversial content, or high monetary value are not appropriate for the general circulating collection. The Rare Books Collection seeks to enable researchers to interact with the physical artifact as much as possible. -

How to Choose a Self-Publishing Service ALLI #1

ALLi (The Alliance of Independent Authors) is the nonprofit professional association for authors who self-publish and want to do it well. Our motto is “Working together to help each other” How to Choose a Self-Publishing Service ALLI #1 As soon as an author starts to consider self-publishing, questions begin to arise. Some are fear-based questions like: What will others think? Will I have the same status as a “properly” published writer? These we can ignore, as we must ignore all self-doubt that interferes with creative output and flow. But valid, work- centered, creative questions also arise: “Do I have what it takes to go it alone and publish well?” “What services and supports do I need?” “What kind of provider is best for me as an author and the book I want to publish?” “How much will it cost me?” “How much can I make? Do I want to make a living at this?” “Who offers the best services for me and this particular project?” It’s not easy. An industry has sprung up We all need editors and good promotional around self-publishing and it’s growing at plans, at a minimum, if we are to do this great speed, with trade publishers who job well. Many others need assistance with traditionally invested in authors now design and production issues and publicity. getting charging for services. This is why author services are now in big demand. To become a self-publisher is to step from one work sector into another. Writing is When demand for any service is high, self-expression; publishing is business, for scammers and schemers circle. -

Barnes & Noble Education, Inc

Index to Form 10-K Index to FS UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K (Mark One) x ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended May 2, 2020 OR ¨ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission File Number: 1-37499 BARNES & NOBLE EDUCATION, INC. (Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in Its Charter) Delaware 46-0599018 (State or Other Jurisdiction of Incorporation or Organization) (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) 120 Mountain View Blvd., Basking Ridge, NJ 07920 (Address of Principal Executive Offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s Telephone Number, Including Area Code: (908) 991-2665 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of Class Trading Symbol Name of Exchange on which registered Common Stock, $0.01 par value per share BNED New York Stock Exchange Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ¨ No x Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Act. Yes ¨ No x Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

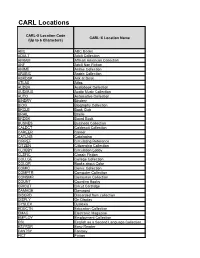

CARL Locations

CARL Locations CARL•X Location Code CARL•X Location Name (Up to 6 Characters) ABC ABC Books ADULT Adult Collection AFRAM African American Collection ANF Adult Non Fiction ANIME Anime Collection ARABIC Arabic Collection ASKDSK Ask at Desk ATLAS Atlas AUDBK Audiobook Collection AUDMUS Audio Music Collection AUTO Automotive Collection BINDRY Bindery BIOG Biography Collection BKCLB Book Club BRAIL Braille BRDBK Board Book BUSNES Business Collection CALDCT Caldecott Collection CAREER Career CATLNG Cataloging CIRREF Circulating Reference CITZEN Citizenship Collection CLOBBY Circulation Lobby CLSFIC Classic Fiction COLLGE College Collection COLOR Books about Color COMIC Comic Collection COMPTR Computer Collection CONSMR Consumer Collection COUNT Counting Books CRICUT Cricut Cartridge DAMAGE Damaged DISCRD Discarded from collection DISPLY On Display DYSLEX Dyslexia EDUCTN Education Collection EMAG Electronic Magazine EMPLOY Employment Collection ESL English as a Second Language Collection ESYRDR Easy Reader FANTSY Fantasy FICT Fiction CARL•X Location Code CARL•X Location Name (Up to 6 Characters) GAMING Gaming Collection GENEAL Genealogy Collection GOVDOC Government Documents Collection GRAPHN Graphic Novel Collection HISCHL High School Collection HOLDAY Holiday HORROR Horror HOURLY Hourly Loans for Pontiac INLIB In Library INSFIC Inspirational Fiction INSROM Inspirational Romance INTFLM International Film INTLNG International Language Collection JADVEN Juvenile Adventure JAUDBK Juvenile Audiobook Collection JAUDMU Juvenile Audio Music Collection -

The Four Paths to Publishing

THE FOUR PATHS TO PUBLISHING Revolutionary changes and unprecedented opportunities in publishing have established four clear paths that authors follow to achieve their publishing goals. by Keith Ogorek Senior Vice President of Marketing and Product Development Author Solutions, Inc. The past four years have brought about more upheaval in the publishing industry than the previous 400 years combined. From the time Gutenberg invented the printing press until the introduction of the paperback about 70 years ago, there weren’t many groundbreaking innovations. However, in the last few years, the publishing world has undergone an indie revolution similar to what occurred in the film and music industries. With the introduction of desktop publishing, print-on-demand technology, and the Internet as a direct-to-consumer distribution channel, publishing became a service consumers could purchase, instead of an industry solely dependent on middlemen (agents) and buyers (traditional publishers). In addition, the exponential growth of e-books and digital readers has accelerated change, because physical stores are no longer the only way for authors to connect with readers. While these changes have made now the best time in history to be an author, they have also made it one of the most confusing times to be an author. Not that long ago, there was only one way to get published: find an agent; hope he or she would represent you; pray they sell your book proposal to a publisher; trust the publisher to get behind the book and believe in the project; and hope that readers would go to their local bookstore and buy your book. -

Fall2011.Pdf

Grove Press Atlantic Monthly Press Black Cat The Mysterious Press Granta Fall 201 1 NOW AVAILABLE Complete and updated coverage by The New York Times about WikiLeaks and their controversial release of diplomatic cables and war logs OPEN SECRETS WikiLeaks, War, and American Diplomacy The New York Times Introduction by Bill Keller • Essential, unparalleled coverage A New York Times Best Seller from the expert writers at The New York Times on the hundreds he controversial antisecrecy organization WikiLeaks, led by Julian of thousands of confidential Assange, made headlines around the world when it released hundreds of documents revealed by WikiLeaks thousands of classified U.S. government documents in 2010. Allowed • Open Secrets also contains a T fascinating selection of original advance access, The New York Times sorted, searched, and analyzed these secret cables and war logs archives, placed them in context, and played a crucial role in breaking the WikiLeaks story. • online promotion at Open Secrets, originally published as an e-book, is the essential collection www.nytimes.com/opensecrets of the Times’s expert reporting and analysis, as well as the definitive chronicle of the documents’ release and the controversy that ensued. An introduction by Times executive editor, Bill Keller, details the paper’s cloak-and-dagger “We may look back at the war logs as relationship with a difficult source. Extended profiles of Assange and Bradley a herald of the end of America’s Manning, the Army private suspected of being his source, offer keen insight engagement in Afghanistan, just as into the main players. Collected news stories offer a broad and deep view into the Pentagon Papers are now a Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and the messy challenges facing American power milestone in our slo-mo exit from in Europe, Russia, Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. -

School of Library and Information Science Central University of Gujarat

School of Library and Information Science Central University of Gujarat Master of Library and Information Science COURSE AND CREDIT STRUCTURE Semester Course Course Title Credits Code 1 LIS-401 Knowledge Society 4 LIS-402 Knowledge Organization I: Classification (Theory & Practice) 3 LIS-403 Knowledge Processing I: Cataloguing (Theory & Practice) 3 LIS-404 Information Sources and Services 4 LIS-405 Information Communication Technology (Theory & Practice) 4 2 LIS-451 Management of Libraries and Information Centres 4 LIS-452 Information Storage and Retrieval 4 LIS-453 Knowledge Organization II: Classification (Theory & Practice) 3 LIS-454 Knowledge Processing II: Cataloguing (Theory & Practice) 3 LIS-455 Library Automation (Theory and Practice) 4 3 LIS-501 Research Methodology 4 LIS-502 Digital Libraries (Theory) 3 LIS-503 Web Technologies and Web-based Information Management 3 (Theory and Practice) LIS-541 Digital Libraries (Practice) 3 LIS-542 Library Internship in a Recognized Library/Information 5 Centre 4 LIS-551 Knowledge Management 4 LIS-552 Informetrics and Scientometrics 3 LIS-571* Social Science Information Systems 3 LIS-572* Community Information Systems LIS-573* Science Information Systems LIS-574* Agricultural Information Systems LIS-575* Health Information Systems LIS-591 Dissertation 8 Total credits 72 *Students are required to select any one course from LIS-571 to LIS-575 1 SEMESTER I Name of the Programme Master of Library and Information Science Course Title Knowledge Society Course Number LIS-401 Semester 1 Credits 4 Objectives of the Course: To introduce the basic concepts of knowledge and its formation To understand the influence of knowledge in the society To understand the process of communication Course Content: Evolution of Knowledge Society, Components, Dimensions, and Indicators of Knowledge Society. -

Fall Conference

NAIBA Fall Conference October 6 - October 8, 2018 Baltimore, MD CONTENTS NAIBA Board of Directors 1 NOTES Letters from NAIBA’s Presidents 2 REGISTRATION HOURS Benefits of NAIBA Membership 4 Schedule At A Glance 6 Constellation Foyer Detailed Conference Schedule 8 Saturday, October 6, Noon – 7:00pm Sunday, October 7, 7:30am – 7:00pm Exhibition Hall Map 23 Monday, October 8, 7:30am – 1:00pm Conference Exhibitors 24 Thank You to All Our Sponsors 34 Were You There? 37 EXHIBIT HALL HOURS Publishers Marketplace Sunday, October 7, 2:00pm – 6:00pm ON BEING PHOTOGRAPHED Participating in the NAIBA Fall Conference and entering any of its events indicates your agreement to be filmed or photographed for NAIBA’s purposes. NO CARTS /naiba During show hours, no hand carts or other similar wheeled naibabooksellers devices are allowed on the exhibit floor. @NAIBAbook #naiba CAN WE TALK? The NAIBA Board Members are happy to stop and discuss retail and association business with you. Board members will be wearing ribbons on their badges to help you spot them. Your input is vital to NAIBA’s continued growth and purpose. NAIBA BOARD OF DIRECTORS Todd Dickinson Trish Brown Karen Torres (Outgoing President) One More Page Hachette Book Group Aaron’s Books 2200 N. Westmoreland Street 1290 6th Ave. 35 East Main Street Arlington, VA 22213 New York, NY 10104 Lititz, PA 17543 Ph: 703-861-8326 212-364-1556 Ph: 717-627-1990 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Jenny Clines Stephanie Valdez Bill Reilly (Incoming Board member) (Outgoing Board member) (Incoming President) Politics & Prose 143 Seventh Ave. -

Please Order Books by Using the Contact Information Listed Under Each Press's Name, Or Visit Your Local Bookstore Or Online R

Please order books by using the contact information listed under each press’s name, or visit your local bookstore or online retailer. DEARTIME PUBLISHER WHITE CLOUD PRESS CLASSICAL GIRL PRESS [email protected], www.deartime.com PO Box 3400, Ashland, OR 97520 1095 Middleton Dr. Boulder Creek CA 95006; (541) 488-6415 (831) 338-4023; DEAR TIME: CIRCLE OF www.whitecloudpress.com www.classicalgirlpress.com, [email protected] LIFE by Jon Ng THE CHARISMA CODE OUTSIDE THE LIMELIGHT Premonitions, nightmares, and paranor- Communicating in a Language Beyond by Terez Mertes Rose mal phenomena bring John and Jeanne Words Kirkus’ Indie Books of the Month Selec- together as they journey the world in by Robin Sol Lieberman tion Jan 2017. Two competing dancer search of answers connecting the past, “The Charisma Code offers a wealth of sisters reexamine loyalty when a devastat- present, and future. tools for resolving conflict, inspiring en- ing medical condition leaves one fighting 9789671457900 • Paperback, $18.99 gagement, and changing culture.” –Tony for her career. “A lovely and engaging tale Hsieh, CEO, Zappos.com. of sibling rivalry in the high-stakes dance 9789671457917 • eBook, $2.99 world.” – Kirkus 9781940468402 • Paper, $18.95 492 pages • Fiction, Epic Fantasy 9780986093432 • Paper, $12.99 240 pages • Leadership / Personal Growth Available on Ingram, barnesandnoble. 390 pages • Contemporary women’s com, amazon.com, & lulu.com. See author’s website: robinsol.com. fiction Also available at amazon.com and your Author website: terezrose.com. Available favorite independent booksellers. through amazon.com and Ingram Book Company. IVORY LEAGUE PUBLISHING NATURE SPEAKS NICK BROWN www.ivoryleaguepublishing.com Art & Poetry for the Earth [email protected], www.theapologybook.com. -

The Materiality of Books and TV House of Leaves and the Sopranos in a World of Formless Content and Media Competition

The Materiality of Books and TV House of Leaves and The Sopranos in a World of Formless Content and Media Competition Alexander Starre* In Western societies, the proliferation of ever new forms of digital media has initiated a fierce competition between various narrative media for the time and attention of readers and viewers. Within the context of the increasingly complex media ecology of the contemporary United States, this paper describes the aes- thetic phenomenon of ‘materiality-based metareference’. Building on theories of mediality and metareference, this specific mode is first described with regard to its general forms and effects. Subsequently, two symptomatic media texts are analyzed in an intermedial comparison between literature and television. The novel House of Leaves (2000) by Mark Z. Danielewski constantly investigates the relationship between its narrative and the printed book, while the serial television drama The Sopranos (1999–2007) ties itself in numerous ways to its apparatus. As these examples show, the increased competition between media fosters narratives which foreground their ultimate adhesion to a fixed material form. Intermedial studies of metareference need to address the mediality of representations, nar- rative and otherwise, in order to fully explain the causes and functions of the increased occurrence of metareference in the digital age. 1. Introduction: from book to content (and back?) On September 17, 2009, Google announced its collaboration with On Demand Books (ODB), a company whose product portfolio consists solely of one item: the Espresso Book Machine (EBM). According to the official press release, this machine “can print, bind and trim a single-copy library-quality paperback book complete with a full-color paperback cover” within minutes (“Google” 2009: online). -

Eretail Services

Why OverDrive? Your Digital Distribution Partner for retail Unique dedication & focus Digital media distribution is all we do. As a leader in this field, we are the only firm dedicated solely to helping you maximize your revenue in this important, growing market. Recognized leader OverDrive has developed an impeccable reputation as a global distributor and infrastructure provider. With the eRetail Services Content Reserve portal and vast distribution network of 8,500 libraries, schools, and retailers around the world, OverDrive has earned a long list of accolades from satisfied customers. eBook & Audiobook Delivery Platform Experience With more than 20 years experience in the digital arena, OverDrive has pioneered many advances in the management, protection, and fulfillment of premium digital content. The Global Leader Proven success in Digital Distribution Whether you’re a publisher or a retailer, OverDrive can help maximize the value of your digital assets. We’ve enabled hundreds of publishers and thousands of libraries, schools, and retailers to do just that. Scalable and flexible OverDrive solutions can grow as you grow. Because we support the entire manage-protect-fulfill process, you Add Value to Your Online Store! not only can add capacity, you can also add channels. - Large collection of digital books & more for your existing or custom-built website Publishers - Proven success at top retailers To apply online: www.contentreserve.com/publisher.asp Retailers - Most compatible service with titles To apply online: www.contentreserve.com/retailer.asp for PC, Mac®, iPod® & Sony® Reader For more information about OverDrive’s services for Publishers, Libraries, Schools & Retailers, please visit www.overdrive.com About OverDrive OverDrive is a leading full-service digital distributor of eBooks, audiobooks, music, and video.