The Dark Knight

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'The Mystery Cruise' Cast Bios Gail O'grady

‘THE MYSTERY CRUISE’ CAST BIOS GAIL O’GRADY (Alvirah Meehan) – Multiple Emmy® nominee Gail O'Grady has starred in every genre of entertainment, including feature films, television movies, miniseries and series television. Her most recent television credits include the CW series “Hellcats” as well as "Desperate Housewives" as a married woman having an affair with the teenaged son of Felicity Huffman's character. On "Boston Legal," her multi-episode arc as the sexy and beautiful Judge Gloria Weldon, James Spader's love interest and sometime nemesis, garnered much praise. Starring series roles include the Kevin Williamson/CW drama series "Hidden Palms," which starred O'Grady as Karen Miller, a woman tormented by guilt over her first husband's suicide and her son's subsequent turn to alcohol. Prior to that, she starred as Helen Pryor in the critically acclaimed NBC series "American Dreams." But O'Grady will always be remembered as the warm-hearted secretary Donna Abandando on the series "NYPD Blue," for which she received three Emmy Award nominations for Best Supporting Actress in a Dramatic Series. O'Grady has made guest appearances on some of television's most acclaimed series, including "Cheers," "Designing Women," "Ally McBeal" and "China Beach." She has also appeared in numerous television movies and miniseries including Hallmark Channel's "All I Want for Christmas" and “After the Fall” and Lifetime's "While Children Sleep" and "Sex and the Single Mom," which was so highly rated that it spawned a sequel in which she also starred. Other television credits include “Major Crimes,” “Castle,” “Hawaii Five-0,” “Necessary Roughness,” “Drop Dead Diva,” “Ghost Whisperer,” “Law & Order: SVU,” “CSI: Miami,” "The Mentalist," "Vegas," "CSI," "Two and a Half Men," "Monk," "Two of Hearts," "Nothing Lasts Forever" and "Billionaire Boys Club." In the feature film arena, O'Grady has worked with some of the industry's most respected directors, including John Landis, John Hughes and Carl Reiner and has starred with several acting legends. -

Theaters 3 & 4 the Grand Lodge on Peak 7

The Grand Lodge on Peak 7 Theaters 3 & 4 NOTE: 3D option is only available in theater 3 Note: Theater reservations are for 2 hours 45 minutes. Movie durations highlighted in Orange are 2 hours 20 minutes or more. Note: Movies with durations highlighted in red are only viewable during the 9PM start time, due to their excess length Title: Genre: Rating: Lead Actor: Director: Year: Type: Duration: (Mins.) The Avengers: Age of Ultron 3D Action PG-13 Robert Downey Jr. Joss Whedon 2015 3D 141 Born to be Wild 3D Family G Morgan Freeman David Lickley 2011 3D 40 Captain America : The Winter Soldier 3D Action PG-13 Chris Evans Anthony Russo/ Jay Russo 2014 3D 136 The Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader 3D Adventure PG Georgie Henley Michael Apted 2010 3D 113 Cirque Du Soleil: Worlds Away 3D Fantasy PG Erica Linz Andrew Adamson 2012 3D 91 Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs 2 3D Animation PG Ana Faris Cody Cameron 2013 3D 95 Despicable Me 3D Animation PG Steve Carell Pierre Coffin 2010 3D 95 Despicable Me 2 3D Animation PG Steve Carell Pierre Coffin 2013 3D 98 Finding Nemo 3D Animation G Ellen DeGeneres Andrew Stanton 2003 3D 100 Gravity 3D Drama PG-13 Sandra Bullock Alfonso Cuaron 2013 3D 91 Hercules 3D Action PG-13 Dwayne Johnson Brett Ratner 2014 3D 97 Hotel Transylvania Animation PG Adam Sandler Genndy Tartakovsky 2012 3D 91 Ice Age: Continetal Drift 3D Animation PG Ray Romano Steve Martino 2012 3D 88 I, Frankenstein 3D Action PG-13 Aaron Eckhart Stuart Beattie 2014 3D 92 Imax Under the Sea 3D Documentary G Jim Carrey Howard Hall -

Batman Year One Proprosal by Larry and Andy

BATMAN YEAR ONE PROPROSAL BY LARRY AND ANDY WACHOWSKI The scene is Gotham City, in the past. A party is going on and from it descends Thomas Wayne with his wife Martha, and son Bruce. They are talking, with Bruce chatting away about how he wants to see The Mark of Zorro again. Obviously they have just come from a movie premiere. As they turn a corner to their car, they are met by a hooded gunman who tries holding them up. There is a struggle and the Wayne parents are murdered in a bloodbath. Bruce is left there, when he is met by a police officer. There is a screech and a bat flies overhead... Twenty years have passed. Bruce is now twenty‐eight and quite dynamic. The main character has been travelling the world, training for a war on crime, to avenge his parents' deaths. He is at the Ludlow International Airport, where his butler Alfred picks him up. The two drive to Wayne Manor, just outside of Gotham. Bruce watches the city from the distance. The scene moves to downtown Gotham, where Bruce is wearing a hockey mask and black clothes. A fight breaks out between him and a pimp which leads to Bruce escaping to a rotting building. Bleeding badly, he doesn't know whether to continue his crusade against crime. A screech fills the area and a bat dives at him, knocking him onto an old chair. Bruce realises his destiny... The opening credits feature Bruce at Wayne Manor, slamming down a hammer on scrap metal, moulding it into shape. -

Movie Museum MAY 2011 COMING ATTRACTIONS

Movie Museum MAY 2011 COMING ATTRACTIONS THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY MONDAY Hawaii Premiere! 2 Hawaii Premieres! BLACK SWAN Mother's Day 2 Hawaii Premieres! SUMO DO, SUMO DON'T LIKE TWO DROPS OF (2010) THE KING'S SPEECH THE ARMY OF CRIME aka Shiko funjatta WATER in widescreen (2010-UK/Australia/US) (2009-France) (1992-Japan) (1963-Netherlands) in widescreen in French/Grman w/ English in Dutch/German with in Japanese with English with Natalie Portman, with Colin Firth, Geoffrey subtitles & in widescreen subtitles & in widescreen English subtitles & widescreen with Simon Abkarian. Directed by Fons Rademakers. Mila Kunis, Vincent Cassel, Rush, Helena Bonham Carter, with Masahiro Motoki, Barbara Hershey, 12:30, 3 & 5:30pm only 12:30 & 3pm only Guy Pearce, Jennifer Ehle, ---------------------------------- Misa Shimizu, Naoto Winona Ryder. Michael Gambon, Derek Jacobi. Takenaka, Akira Emoto. ---------------------------------- LIKE TWO DROPS OF THE ARMY OF CRIME WATER Written and Directed by (2009-France) Directed by Directed by (1963-Netherlands) Masayuki Suo. in French/Grman w/ English Darren Aronofsky. Tom Hooper. in Dutch/German with subtitles & in widescreen English subtitles & widescreen 12:30, 2:30, 4:30, 6:30 with Simon Abkarian. 12:30, 2:30, 4:30, 6:30 12:15, 2:30, 4:45, 7:00 & Directed by Fons Rademakers. & 8:30pm 9:15pm 8pm only & 8:30pm 5 5:30 & 8pm only 6 7 8 9 2 Hawaii Premieres! THE MAGIC HOUR BLUE VALENTINE Hawaii Premiere! 2 Hawaii Premieres! KATALIN VARGA JE VOUS TROUVE (2008-Japan) (2010) THE TIGER BRIGADES TRÈS BEAU aka -

The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Theses Department of English 12-2009 Static, Yet Fluctuating: The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences Perry Dupre Dantzler Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Dantzler, Perry Dupre, "Static, Yet Fluctuating: The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2009. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses/73 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STATIC, YET FLUCTUATING: THE EVOLUTION OF BATMAN AND HIS AUDIENCES by PERRY DUPRE DANTZLER Under the Direction of H. Calvin Thomas ABSTRACT The Batman media franchise (comics, movies, novels, television, and cartoons) is unique because no other form of written or visual texts has as many artists, audiences, and forms of expression. Understanding the various artists and audiences and what Batman means to them is to understand changing trends and thinking in American culture. The character of Batman has developed into a symbol with relevant characteristics that develop and evolve with each new story and new author. The Batman canon has become so large and contains so many different audiences that it has become a franchise that can morph to fit any group of viewers/readers. Our understanding of Batman and the many readings of him gives us insight into ourselves as a culture in our particular place in history. -

Die Superschurken Greifen An!

Die Superschurken greifen an! Bearbeitet von J. E. Bright, Laurie S. Sutton, Jane Mason, Leo H. Strohm, Shawn McManus, Luciano Vecchio 1. Auflage 2015. Buch. 208 S. Hardcover ISBN 978 3 596 85674 9 Format (B x L): 14,6 x 21,5 cm Gewicht: 518 g schnell und portofrei erhältlich bei Die Online-Fachbuchhandlung beck-shop.de ist spezialisiert auf Fachbücher, insbesondere Recht, Steuern und Wirtschaft. Im Sortiment finden Sie alle Medien (Bücher, Zeitschriften, CDs, eBooks, etc.) aller Verlage. Ergänzt wird das Programm durch Services wie Neuerscheinungsdienst oder Zusammenstellungen von Büchern zu Sonderpreisen. Der Shop führt mehr als 8 Millionen Produkte. Unverkäufliche Leseprobe aus: J.E., Bright Laurie S., Sutton Jane, Mason Die Superschurken greifen an Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Die Verwendung von Text und Bildern, auch auszugsweise, ist ohne schriftliche Zustimmung des Verlags urheber rechts- widrig und strafbar. Dies gilt insbesondere für die Verviel fältigung, Übersetzung oder die Verwendung in elektronischen Systemen. © S. Fischer Verlag GmbH, Frankfurt am Main ENTHÄLT DIE GESCHICHTEN: DER JOKER AUF HOHER SEE SINESTRO UND DAS RAD DES SCHRECKENS BLACK MANTA UND DIE TINTENFISCH-ARMEE Copyright © 2015 DC Comics. All related characters and elements are trademarks of and © DC Comics. (s15) SFIS34249 Sammelband Erschienen bei FISCHER KJB Die amerikanischen Originalausgaben der drei Einzelbände erschienen 2012 unter den Titeln ,Joker on the High Seas‘, ‚Sinestro and the Ring of Fear‘ und ‚Black Manta and the Octopus Army‘ bei Stone Arch Books, A Capstone Imprint, Mankato, Minnesota, USA Für die deutschsprachige Ausgabe: © S. Fischer Verlag GmbH, Frankfurt am Main 2015 Umschlaggestaltung: Suse Kopp, Hamburg Satz: pagina GmbH, Tübingen Druck und Bindung: CPI books GmbH, Leck Printed in Germany ISBN 978-3-596-85674-9 Auf hoher See GESCHRIEBEN VON J.E. -

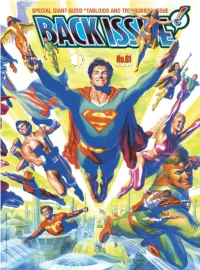

No.61 2 1 0 2

D e c . 2 0 1 2 No.61 $10.95 Legion of Super-Heroes TM & © DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. Rights All Comics. DC © & TM Super-Heroes of Legion Volume 1, Number 61 December 2012 EDITOR-IN- CHIEF Michael Eury Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTIST Alex Ross COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER FLASHBACK: The Perils of the DC/Marvel Tabloid Era . .1 Rob Smentek Pitfalls of the super-size format, plus tantalizing tabloid trivia SPECIAL THANKS BEYOND CAPES: You Know Dasher and Dancer: Rudolph the Red-Nosed Rein- Jack Abramowitz Dan Jurgens deer . .7 Neal Adams Rob Kelly and The comics comeback of Santa and the most famous reindeer of all Erin Andrews TreasuryComics.com FLASHBACK: The Amazing World of Superman Tabloids . .11 Mark Arnold Joe Kubert A planned amusement park, two movie specials, and your key to the Fortress Terry Austin Paul Levitz Jerry Boyd Andy Mangels BEYOND CAPES: DC Comics’ The Bible . .17 Rich Bryant Jon Mankuta Kubert and Infantino recall DC’s adaptation of the most spectacular tales ever told Glen Cadigan Chris Marshall FLASHBACK: The Kids in the Hall (of Justice): Super Friends . .24 Leslie Carbaga Steven Morger A whirlwind tour of the Super Friends tabloid, with Alex Toth art Comic Book Artist John Morrow Gerry Conway Thomas Powers BEYOND CAPES: The Secrets of Oz Revealed . .29 DC Comics Alex Ross The first Marvel/DC co-publishing project and its magical Marvel follow-up Paul Dini Bob Rozakis FLASHBACK: Tabloid Team-Ups . .33 Mark Evanier Zack Smith The giant-size DC/Marvel crossovers and their legacy Jim Ford Bob Soron Chris Franklin Roy Thomas INDEX: Bronze Age Tabloids Checklist . -

Erin Brockovich

Erin Brockovich Dir: Steven Soderbergh, USA, 2000 A review by Matthew Nelson, University of Wisconsin- Madison, USA When a film opens with the title "based on a true story," a sinking feeling of gloom comes over me. Will this be yet another typical triumph over adversity, human-interest flick, cranked out by the Hollywood machine to force-feed an increasingly lazy mass audience interested only in star power and happy endings? The lack of original story lines and plot conventions has turned the American motion picture industry into a creator of shallow popular interest films bested in their absurdity and lack of depth only by made-for-TV movies. While it has been said that our greatest stories come from real life, the griminess of the modern world rarely fits into the tightly regulated limitations surrounding mainstream American screenwriting. Details that do not fit within the formula of a marketable "true story" film, which must attempt to appeal to a large audience base of diverse people, are edited out in favor of more pleasing elements, such as a love story, gripping court room confession, or death bed recovery. With this admittedly jaded viewpoint, I went into Erin Brockovich hoping for the best (a rather vacant, feel-good movie, forgotten before I had pulled out of the multi-plex parking garage), but expected far worse. To my pleasant surprise, it turned out to be neither. Director Steven Soderbergh (of Sex, Lies and Videotape fame) manages to pull off an amazingly interesting film, with snappy writing, fine casting, and plenty of that feel good energy, that does not fall into sugary sentimentalism. -

Domestic Affairs

CAT-TALES DDOMESTIC AAFFAIRS CAT-TALES DDOMESTIC AAFFAIRS By Chris Dee Edited by David L. COPYRIGHT © 2001 BY CHRIS DEE ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. BATMAN, CATWOMAN, GOTHAM CITY, ET AL CREATED BY BOB KANE, PROPERTY OF DC ENTERTAINMENT, USED WITHOUT PERMISSION DOMESTIC AFFAIRS I was in the mood to celebrate. Lexcorp was pulling out of Gotham City! As soon as I saw the headline, I headed over to a popular coffee shop in the financial district to eavesdrop on the brokers. The rumor mill was saying Lex Luthor got wind of the enormous sums Talia was spending on the war with Wayne Enterprises and ordered her to knock it off. Meow—Purr—and Hot Damn, Yippie KaiYay! ‘Course Luthor had no idea why she was in Gotham in the first place, probably assumed she was just following his lead during No Man’s Land. If he knew she was focused on Wayne Enterprises because of a personal obsession with Bruce, or that she was spending so much because she was chasing bogus research and products we deliberately planted for her to uncover, he’d have fired her worthless ass. But we can’t have everything. The important thing was: she was gone—at least until she makes it up with Daddy (and she will, let’s not kid ourselves about that). So anyway, I was in the mood to celebrate. Picked up a bottle of champagne and headed out to the manor. Now Alfred answers by the third ring, always. So after five rings and six knocks, I was quite sure he’d taken the day off. -

Justice League: Origins

JUSTICE LEAGUE: ORIGINS Written by Chad Handley [email protected] EXT. PARK - DAY An idyllic American park from our Rockwellian past. A pick- up truck pulls up onto a nearby gravel lot. INT. PICK-UP TRUCK - DAY MARTHA KENT (30s) stalls the engine. Her young son, CLARK, (7) apprehensively peeks out at the park from just under the window. MARTHA KENT Go on, Clark. Scoot. CLARK Can’t I go with you? MARTHA KENT No, you may not. A woman is entitled to shop on her own once in a blue moon. And it’s high time you made friends your own age. Clark watches a group of bigger, rowdier boys play baseball on a diamond in the park. CLARK They won’t like me. MARTHA KENT How will you know unless you try? Go on. I’ll be back before you know it. EXT. PARK - BASEBALL DIAMOND - MOMENTS LATER Clark watches the other kids play from afar - too scared to approach. He is about to give up when a fly ball plops on the ground at his feet. He stares at it, unsure of what to do. BIG KID 1 (yelling) Yo, kid. Little help? Clark picks up the ball. Unsure he can throw the distance, he hesitates. Rolls the ball over instead. It stops halfway to Big Kid 1, who rolls his eyes, runs over and picks it up. 2. BIG KID 1 (CONT’D) Nice throw. The other kids laugh at him. Humiliated, Clark puts his hands in his pockets and walks away. Big Kid 2 advances on Big Kid 1; takes the ball away from him. -

Catwoman (White Queen)

KNI_05_p01 CS6.indd 1 10/09/2020 10:41 IN THIS ISSUE YOUR PIECE Meet your white queen – Gotham City’s 3 ultimate femme fatale Selina Kyle, better known as Catwoman. PROFILE From the slums of Gotham City’s East 4 End, Catwoman has become one of the world’s most famous thieves. GOTHAM GUIDE A examination of Gotham’s East End, a 10 grim area of crime and poverty – and the home of Selina Kyle. RANK & FILE Why Catwoman is the white queen and 12 how some of her moves are refl ected in those of the powerful chess piece. RULES & MOVES An essential guide to the white queen 15 and some specifi c gambits using the piece. Editor: Alan Cowsill Thanks to: Art Editor: Gary Gilbert Writers: Devin K. Grayson, Ed Brubaker, Frank Writer: James Hill Miller, Jeph Loeb, Will Pfeifer, Judd Winick, Consultant: Richard Jackson Darwyn Cooke, Andersen Grabrych. Figurine Sculptor: Imagika Sculpting Pencillers: Jim Balent, Michael Avon Oeming, Studio Ltd David Mazzucchelli, Cameron Stewart, Jim Lee, Pete Woods, Guillem March, Darwyn US CUSTOMER SERVICES Cooke, Brad rader, Rick Burchett. Call: +1 800 261 6898 Inkers: John Stanisci, Mike Manley, Scott Email: [email protected] Williams, Mike Allred, Rick Burchett, Cameron Stewart, Alavaro Lopez. UK CUSTOMER SERVICES Call: +44 (0) 191 490 6421 Email: [email protected] Batman created by Bob Kane with Bill Finger Copyright © 2020 DC Comics. CATWOMAN and all related characters and elements © and TM DC Comics. (s20) EAGL26789 Collectable Figurines. Not designed or intended for play by children. Do not dispose of fi gurine in the domestic waste. -

Dawn of Justice: the DCEU Timeline Explained Pages

Dawn of Justice: The DCEU Timeline Explained Pages: Full Timeline Explained: pg 2 Sources: pg 15 Continuity Errors?: pg 17 !1 4,500,000,000 BCE: • Earth forms. 98,020 BCE: • Krypton's civilization begins to flourish, with its people developing impressive technology. 18,635 BCE: • A class of Kryptonian pilots, including Kara Zor-El, Dev-Em, and Kell-Ur, train for the upcoming interstellar terraforming program Krypton is about to undergo. In order to ensure his acceptance into the program, Dev-Em kills Kell-Ur and attacks Kara Zor-El, but is stopped and handed over to the Kryptonian council by Kara. • The terraforming program begins on Krypton, with thousands of ships sent into the universe in order to colonize more planets. Kara Zor-El and her crew enter their cryopods and sleep, waiting to land on their chosen planet. 18,625 BCE: • Kara Zor-El wakes up in her pod and discovers that Dev-Em not only entered her ship, but also changed the ship's destination to Earth and killed the rest of her crew. The two battle it out, each getting stronger as they get closer to the Sun. The ship is damaged during the scuffle. • Kara wins the battle, although she cannot maintain control of the ship. It crash lands in what is now Canada. She places the dead crew in their pods and wanders into the icy wilderness. 4,357 BCE: • Dzamor and Incubus are born. 2,983 BCE: • Steppenwolf invades Earth.* o *One of the Amazons in Justice League mentioned that the warning signal hadn’t been used for 5,000 years.