Quality in Education?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Benchmarking Tree Canopy in Sydney's Hot Schools

BENCHMARKING TREE CANOPY IN SYDNEY’S HOT SCHOOLS OCTOBER 2020 WESTERN SYDNEY UNIVERSITY AUTHORS Sebastian Pfautsch, Agnieszka Wujeska-Klause, Susanna Rouillard Urban Studies School of Social Sciences Western Sydney University, Parramatta, NSW 2150, Australia With respect for Aboriginal cultural protocol and out of recognition that the campuses of Western Sydney University occupy their traditional lands, the Darug, Tharawal (also historically referred to as Dharawal), Gandangara and Wiradjuri people are acknowledged and thanked for permitting this work in their lands (Greater Western Sydney and beyond). This research project was funded by Greening Australia. SUGGESTED CITATION Pfautsch S., Wujeska-Klause A., Rouillard S. (2020) Benchmarking tree canopy in Sydney’s hot schools. Western Sydney University, 40 p. DOI: https://doi.org/10.26183/kzr2-y559 ©Western Sydney University. www.westernsydney.edu.au October, 2020. Image credits: pages 18 and 23 ©Nearmap, other images from istock.com. 2 Western Sydney University Urban parks and school yards with adequate vegetation, shade, and green space have the potential to provide thermally comfortable environments and help reduce vulnerability to heat stress to those active within or nearby. However, in order to provide this function, outdoor spaces, including parks and schoolyards, must be designed within the context of the prevailing urban climate and projected future climates. JENNIFER K. VANOS (ENVIRONMENT INTERNATIONAL, 2015) westernsydney.edu.au 3 WESTERN SYDNEY UNIVERSITY SUMMARY This project identified the 100 most vulnerable schools to heat in Greater Western Sydney using a newly developed Heat Score. The Heat Score combines socio-economic information that captures exposure, sensitivity and adaptivity of local communities to heat with environmental data related to surface and air temperatures of urban space. -

Families, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs Portfolio

Community Affairs Committee Examination of Budget Estimates 2006-2007 Additional Information Received VOLUME 2 HEALTH AND AGEING PORTFOLIO Outcomes: whole of portfolio and Outcomes 1, 2, 3 OCTOBER 2006 Note: Where published reports, etc. have been provided in response to questions, they have not been included in the Additional Information volume in order to conserve resources. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION RELATING TO THE EXAMINATION OF BUDGET EXPENDITURE FOR 2006-2007 Included in this volume are answers to written and oral questions taken on notice and tabled papers relating to the budget estimates hearings on 31 May and 1 June 2006 * Please note that the tabling date of 19 October 2006 is the proposed tabling date HEALTH AND AGEING PORTFOLIO Senator Quest. Whole of portfolio Vol. 2 Date tabled No. Page No. in the Senate* T2 DoHA addresses/organisation unit occupying/lease expiry 1 17.08.06 tabled at date hearing Crossin 55 Rock Eisteddfod 2 17.08.06 McLucas 118 Skin cancer national awareness 3 17.08.06 McLucas 249 Response time to questions from Parliamentary Library 4 17.08.06 Mason 9 Sick leave 5 17.08.06 McLucas 145 PBS and the 2007 Intergenerational Report 6-7 17.08.06 Ludwig 1 Expenditure on legal services 8-9 17.08.06 McLucas 90 Secretary's overseas travel 10 17.08.06 Ludwig 2 Executive coaching and/or other leadership training 11-14 14.09.06 Moore/ 192, Description of the methodology used to create and maintain 15-17 14.09.06 McLucas 250 notional allocations of Departmental funds McLucas 251 Department of Health and Ageing structure -

Cumberland Historical Timeline

Cumberland Historical Timeline Author: Jane Elias Local & Family History Librarian May 2021 Contents Pre-European Period – Pre-1788 ........................................................................................... 3 Early Colonial Period – 1788 to 1843 ..................................................................................... 3 Mid-Colonial Period – 1855 to 1879 ...................................................................................... 6 Late Colonial Period – 1880 to 1899 .................................................................................... 10 Early 20th Century – 1900 to 1913 ....................................................................................... 17 World War I – 1914 to 1918 ................................................................................................ 20 Inter-War Period – 1919 to 1939 ......................................................................................... 22 World War II – 1939 to 1945 ............................................................................................... 30 Post-War Period – 1946 to 1979 .......................................................................................... 32 Late 20th Century – 1981 to 1999 ........................................................................................ 45 21st Century – 2000 to 2020 ................................................................................................ 47 2 Date Event Pre-European Period – Pre-1788 Pre– The land that is now part of Cumberland -

Official Hansard No

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES SENATE Official Hansard No. 7, 2000 6 JUNE 2000 THIRTY-NINTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION—SIXTH PERIOD BY AUTHORITY OF THE SENATE CONTENTS TUESDAY, 6 JUNE Questions Without Notice Goods and Services Tax: Exploitation......................................................... 14641 Industrial Relations: Level of Disputation................................................... 14641 Aboriginals: Living Conditions................................................................... 14642 Private Health Insurance: Government Initiatives....................................... 14644 Centrelink: Client Privacy ........................................................................... 14645 Cox Peninsula Transmitter: Sale ................................................................. 14646 Goods and Services Tax: Australian Business Number Records................. 14646 Timber Industry: Plantations ....................................................................... 14647 Goods and Services Tax: Australian Business Number Records................. 14648 Goods and Services Tax: Local Government .............................................. 14649 Goods and Services Tax: Advertising.......................................................... 14650 Heritage Protection Order: Boobera Lagoon............................................... 14652 Answers To Questions Without Notice Goods and Services Tax: Information ......................................................... 14653 Goods and Services Tax ............................................................................. -

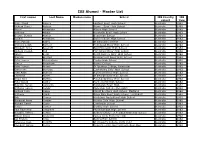

ISS Alumni - Master List

ISS Alumni - Master List First names Last Name Maiden name School ISS Country ISS cohort Year Brian David Aarons Fairfield Boys' High School Australia 1962 Richard Daniel Aldous Narwee Boys' High School Australia 1962 Alison Alexander Albury High School Australia 1962 Anthony Atkins Hurstville Boys' High School Australia 1962 George Dennis Austen Bega High School Australia 1962 Ronald Avedikian Enmore Boys' High School Australia 1962 Brian Patrick Bailey St Edmund's College Australia 1962 Anthony Leigh Barnett Homebush Boys' High School Australia 1962 Elizabeth Anne Beecroft East Hills Girls' High School Australia 1962 Richard Joseph Bell Fort Street Boys' High School Australia 1962 Valerie Beral North Sydney Girls' High School Australia 1962 Malcolm Binsted Normanhurst Boys' High School Australia 1962 Peter James Birmingham Casino High School Australia 1962 James Bradshaw Barker College Australia 1962 Peter Joseph Brown St Ignatius College, Riverview Australia 1962 Gwenneth Burrows Canterbury Girls' High School Australia 1962 John Allan Bushell Richmond River High School Australia 1962 Christina Butler St George Girls' High School Australia 1962 Bruce Noel Butters Punchbowl Boys' High School Australia 1962 Peter David Calder Hunter's Hill High School Australia 1962 Malcolm James Cameron Balgowlah Boys' High Australia 1962 Anthony James Candy Marcellan College, Randwich Australia 1962 Richard John Casey Marist Brothers High School, Maitland Australia 1962 Anthony Ciardi Ibrox Park Boys' High School, Leichhardt Australia 1962 Bob Clunas -

ACER Research Conference Proceedings (2012)

2012 School Improvement: What does research tell us about effective strategies? 26–28 August 2012 Sydney Convention and Exhibition Centre Darling Harbour, NSW Australian Council for Educational Research Conference Proceedings Contents Foreword v Keynote papers Professor Geoff N. Masters 3 Continual improvement through aligned effort Professor David H. Hargreaves 8 Endgame: a self-improving school system Dr Michele Bruniges 9 Developing and implementing an explicit school improvement agenda Ms Valerie Hannon 16 Innovating a new future for learning: Finding our path Concurrent papers Professor Kathryn Moyle 23 Differentiated classroom learning, technologies and school improvement: What experience and research can tell us Professor Brian Caldwell and Dr Tanya Vaughan 29 Transforming education through the Arts: Creating a culture that promotes learning Professor Stephen Dinham 34 Walking the walk: The need for school leaders to embrace teaching as a clinical practice profession Professor Helen Timperley 40 Building professional capability in school improvement Professor Helen Wildy 44 Using data to drive school improvement Associate Professor John Munro 48 Effective strategies for implementing differentiated instruction Mr Brian Giles-Browne and Ms Gina Milgate 55 Improving school practices for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students: The voices of their parents and carers Professor Mike Askew 59 Effective teaching: Lessons from mathematics Dr John Ainley 63 Lessons for improvement from international comparative studies Mr Mark Campling, -

2015 Annual Report

2015 Annual Report Contents Catholic Education Commission NSW 1. TRANSMITTAL LETTER 5 2. CHAIRMAN’S REPORT 6 3. EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR’S REPORT 7 4. Governance 9 5. NSW Catholic Schools 16 6. Advocacy, Consultation and Engagement 19 7. School Resourcing 32 8. Education Services to Schools 36 9. Legislative monitoring and compliance 39 Secretariat 1. Our people 42 2. Executive Director’s Office 43 3. Education Policy and Programs 43 4. Resources Policy and Capital Programs 45 5. Corporate Services 46 Appendix A: 2015 Financial Report 47 Appendix B: Commission Core Committees and Working Parties 65 TRANSMITTAL LETTER 1. TRANSMITTAL LETTER Most Reverend Michael McKenna Secretary Trustees of the Province of Sydney and Archdiocese of Canberra and Goulburn 118 Keppel Street BATHURST NSW 2795 My Lord, It is with great pleasure that I submit the 2015 Annual Report of the Catholic Education Commission New South Wales (CECNSW) for the consideration of The Trustees of the Province of Sydney and Archdiocese of Canberra and Goulburn. In accord with its Charter from the Bishops, the Commission continues to carry out its role of overseeing the disbursement of funds from the Australian and NSW Governments as well as representing the Catholic Schools sector and advocating on its behalf. This is evident in this report. I commend the 2015 CECNSW Annual Report to the NSW/ACT Bishops. Yours fraternally in Christ Bishop Peter A Comensoli DD Chairman 18 May 2016 2015 Annual Report | 5 CHAIRMAN’S REPORT 2. CHAIRMAN’S REPORT Commission and Secretariat to ensure that all Catholic schools in NSW understand the new legal requirements It is with great pleasure that I present my second report as including the training of all Responsible Persons. -

Chairpersons Annual Report 2012

CHAIRPERSONS ANNUAL REPORT 2012 It gives me great pleasure to present this annual report on behalf of the executive, diocesan and association representatives and individual sport conveners. The scope of this report reflects another amazing year of sporting achievement for our catholic school students and staff in secondary schools across NSW. It provides a reflection of the incredible talent we have in our schools and the pathways that are available in a wide variety of sports. It is always rewarding to see students from our catholic secondary schools listed as members of NSW All School and Australian teams. Pope Benedict XVI in praying for this year’s London Olympic and Paralympic Games hoped for the promotion of world peace and friendship emphasizing the positive role that sports can play in society. He said, “the Olympics are the greatest sporting event in the world, at which athletes from a great many nations participate, and as such they have a strong symbolic value. The Games remind us of human endeavour and ambition at its most pure; the will to come together to measure our abilities and soar to ever greater heights in the name not of profit or greed but, in the words of the Olympic Charter: “at the service of the harmonious development of man, with a view to promoting a peaceful society concerned with the preservation of human dignity” Our NSWCCC sporting activities can foster these great values and are further testimony to the spirit of partnership and co-operation that are part of our Catholic education tradition. The report that follows is a most detailed account of the many sporting events for the year. -

Gratitude ~ Passion Hope PATRICIAN INTERNATIONAL NEWSLETTER Number 40 DECEMBER 2020

Gratitude ~ Passion Hope PATRICIAN INTERNATIONAL NEWSLETTER Number 40 DECEMBER 2020 The Christ is With Us! Let us Rejoice and be Glad! PATRICIAN INTERNATIONAL NEWSLETTER DECEMBER 2020 Dear Brothers and friends, This year were find ourselves experiencing the mystery of Christ’s birth against the threatening backdrop of a pandemic, the likes of which humanity has not witnessed in over a century. Four Patricians – three in India, one in Kenya - contracted Co- vid-19 but thankfully recovered. I am immensely grateful to Community Leaders who keep our most vulnerable Brothers safe and immensely proud of Brothers in various administrative roles who try their utmost to protect the livelihoods of our employees and organise food relief. They are potent signs of solidarity within and beyond ourselves. A very much prized value within in our Patrician family is capacity for cultivating a global outlook. Our cultural diversity and geographic spread are graces for being ‘Brothers without borders’. In his October 2020 encyclical Fratelli Tutti, Pope Francis urges nations to be ‘Neighbours without borders’, so as to dispel “The dark clouds over a closed world’ and nurture hearts ‘Open to the whole world’. Our Pope unashamedly pro- vokes humanity with the example of the Good Samaritan. It was a ‘stranger and nobody’, who freely, gener- ously and at considerable personal cost, unhesitatingly suspended his personal journey and agenda. These days vigilance is required of us, lest the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on our respective nations erodes our commitment or narrows our perspective. For millions of people around the world, Christmas 2020 and New Year 2021 will difficult, if not altogether bleak due to the separations, suffering, death and economic loss caused by the Corona virus. -

Ireland / Kenya Newsletter

IRELAND / KENYA NEWSLETTER Patrician Brothers October 2014 Tragic loss of two Presentation Sisters Sister Paula Buckley Sister Imelda Carew In common with all Congregations in Ireland we offer our deepest sympathy to the Presentation Congregation on the accidental death by drowning of two of their sisters, Imelda and Paula. As they had been doing over many years of committed religious living, Paula, in her various ministries, and Imelda, as Provincial Leader of the South Eastern Province and member for the last two years of the CORI Executive, were continuing to make a huge contribution to the life of the Presentation Family and to the life of the Church in Ireland. The following is part of the homily delivered by Bishop Denis Nulty of Kildare & Leighlin during the funeral Mass for Sister Imelda: “Enjoying the peace of the evening time and the beauty of that place in the Kerry kingdom; letting ourselves go in the freedom of the purest and freshest water … aren’t all religious and priests called to let go, how often Imelda and all of us heard those words in Luke’s and Mark’s gospel: “take nothing with you for the journey”. Last Thursday both Imelda and Paula were called to the ultimate understanding of letting go, knowing that that going was into the freedom and the peace of God’s presence. For colleagues, family and friends that ultimate letting go is a huge ask in terms of the shock factor, the stunned reaction, the search for meaning and words. And so often death robs us of much more than the loss of someone we have loved, we have cherished, we have appreciated … their death robs us of our own sense of security, our own future plans, our own sense of place and presence.” News from Finglas All is changed As has already been announced, Patrician College, Finglas, has been amalgamated with Mater Christi Girls! School to form New Cross College. -

Using Data to Support Learning (Conference Proceedings)

Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER) ACEReSearch 2005 - Using data to support learning 1997-2008 ACER Research Conference Archive 2005 Using Data to Support Learning (Conference Proceedings) Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER) Follow this and additional works at: https://research.acer.edu.au/research_conference_2005 Part of the Educational Assessment, Evaluation, and Research Commons Recommended Citation Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER), "Using Data to Support Learning (Conference Proceedings)" (2005). https://research.acer.edu.au/research_conference_2005/2 This Book is brought to you by the 1997-2008 ACER Research Conference Archive at ACEReSearch. It has been accepted for inclusion in 2005 - Using data to support learning by an authorized administrator of ACEReSearch. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Australian Council for Educational Research ACEReSearch 2005 - Using data to support learning Research Conferences 8-28-2008 Using Data to Support Learning (Conference Proceedings) Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER) Recommended Citation Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER), "Using Data to Support Learning (Conference Proceedings)" (2008). 2005 - Using data to support learning. http://research.acer.edu.au/research_conference_2005/2 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Research Conferences at ACEReSearch. It has been accepted for inclusion in 2005 - Using data to support learning by an authorized administrator of -

New South Wales Cross Country Championships

New South Wales Catholic Primary Schools and Combined Catholic Colleges Cross Country Championships Sydney Motorsport Park Friday 12 June 2015 Table of Contents Welcome .................................................................... 2 Conveners’ Message ................................................. 2 NSWCCC Sports Association Representatives ......... 3 NSWCPS Sports Council Representatives ................ 3 Officials ..................................................................... 4 Course Officials ......................................................... 4 Event Program .......................................................... 5 General Information .................................................. 6 Primary Rules ........................................................... 6 Secondary Rules ...................................................... 7 Athletes with a Disability (AWD) ............................... 8 Competitors & Team Managers ................................ 10 Acknowledgements ..................................................... 45 Seating plan .............................................................. 47 Course / Venue Map ................................................. 48 1 WELCOME It is with great pleasure that I welcome students, teachers, parents and friends to the NSW Catholic Primary Schools (CPS) and NSW Combined Catholic Colleges (CCC) Cross Country Championships. This annual Championship brings together students from Catholic Primary and Secondary Schools. It is an achievement for every