“Entangled in Metaphors”: Visions and Notions in Middlemarch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saint Maximus the Confessor and His Defense of Papal Primacy

Love that unites and vanishes: Saint Maximus the Confessor and his defense of papal primacy Author: Jason C. LaLonde Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:108614 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2019 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Love that Unites and Vanishes: Saint Maximus the Confessor and his Defense of Papal Primacy Thesis for the Completion of the Licentiate in Sacred Theology Boston College School of Theology and Ministry Fr. Jason C. LaLonde, S.J. Readers: Fr. Brian Dunkle, S.J., BC-STM Dr. Adrian Walker, Catholic University of America May 3, 2019 2 Introduction 3 Chapter One: Maximus’s Palestinian Provenance: Overcoming the Myth of the Greek Life 10 Chapter Two: From Monoenergism to Monotheletism: The Role of Honorius 32 Chapter Three: Maximus on Roman Primacy and his Defense of Honorius 48 Conclusion 80 Appendix – Translation of Opusculum 20 85 Bibliography 100 3 Introduction The current research project stems from my work in the course “Latin West, Greek East,” taught by Fr. Brian Dunkle, S.J., at the Boston College School of Theology and Ministry in the fall semester of 2016. For that course, I translated a letter of Saint Maximus the Confessor (580- 662) that is found among his works known collectively as the Opuscula theologica et polemica.1 My immediate interest in the text was Maximus’s treatment of the twin heresies of monoenergism and monotheletism. As I made progress -

Water Island US Virgin Islands Title Transfer

\ \ \ X \ Water Island U.S. Virgin Islands Title Transfer Final Environmental Assessment and Finding of No Significant Impact May 1996 United States Department of the Interior 200.If I02VI097701 01.06 0013 Final Environmental Assessment Finding of No Significant Impact Water Island, U.S. Virgin Islands Title Transfer Lead agency: Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Responsible official: Director Office of Insular Affairs For further information contact: Deanna Miller, Activity Manager Bureau of Reclamation D-8650 PO Box 25007 Denver CO 80225 (303) 236-8299 ext. 454 Abstract: The final environmental assessment (EAVfinding of no significant impact documents the analysis of no action and three other alternatives and multiple options that were developed for the title transfer of Water Island. The alternatives are to (1) offer the land for sale (various options), (2) turn the island over to the Virgin Islands (V.I.) Government or to former sublessees via a life estate, and (3) combination, offer land for sale and turn over part to V.I. Government. The preferred alternative is the combination, offer land for sale and turn over part to the V.I. Government. This final EA was prepared in compliance with the National Environmental Policy Act and Bureau of Reclamation procedures and is intended to serve the environmental review and consultation requirements pursuant to Executive Order 11990 (Wetlands Protection), National Historic Preservation Act (Section 106), Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act, and the Endangered Species Act (Section 7c). The Department of the Interior (Interior) is not required to seek comments on the final EA. The Bureau of Reclamation and the Interior thank everyone who provided comments, recommendations, or objections on the draft EA so that comments may be considered and responded to in this final EA. -

Comparative Saints' Cults of St Catherine of Alexandria and Rabi'a of Basr

Eylül Çetinbaş A BRIDE OF CHRIST AND AN INTERCESSOR OF MUHAMMAD: COMPARATIVE SAINTS’ CULTS OF ST CATHERINE OF ALEXANDRIA AND RABI’A OF BASRA IN THE MIDDLE AGES MA Thesis in Late Antique, Medieval and Early Modern Studies Central European University Budapest June 2020 CEU eTD Collection A BRIDE OF CHRIST AND AN INTERCESSOR OF MUHAMMAD: COMPARATIVE SAINTS’ CULTS OF ST CATHERINE OF ALEXANDRIA AND RABI’A OF BASRA IN THE MIDDLE AGES by Eylül Çetinbaş (Turkey) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Late Antique, Medieval and Early Modern Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ Examiner ____________________________________________ Examiner CEU eTD Collection Budapest June 2020 A BRIDE OF CHRIST AND AN INTERCESSOR OF MUHAMMAD: COMPARATIVE SAINTS’ CULTS OF ST CATHERINE OF ALEXANDRIA AND RABI’A OF BASRA IN THE MIDDLE AGES by Eylül Çetinbaş (Turkey) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Late Antique, Medieval and Early Modern Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ External Reader CEU eTD Collection Budapest June 2020 A BRIDE OF CHRIST AND AN INTERCESSOR OF MUHAMMAD: COMPARATIVE SAINTS’ CULTS OF ST CATHERINE OF ALEXANDRIA AND RABI’A OF BASRA IN THE MIDDLE AGES by Eylül Çetinbaş (Turkey) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Late Antique, Medieval and Early Modern Studies. -

Baby Girl Names Registered in 2018

Page 1 of 46 Baby Girl Names Registered in 2018 Frequency Name Frequency Name Frequency Name 8 Aadhya 1 Aayza 1 Adalaide 1 Aadi 1 Abaani 2 Adalee 1 Aaeesha 1 Abagale 1 Adaleia 1 Aafiyah 1 Abaigeal 1 Adaleigh 4 Aahana 1 Abayoo 1 Adalia 1 Aahna 2 Abbey 13 Adaline 1 Aaila 4 Abbie 1 Adallynn 3 Aaima 1 Abbigail 22 Adalyn 3 Aaira 17 Abby 1 Adalynd 1 Aaiza 1 Abbyanna 1 Adalyne 1 Aaliah 1 Abegail 19 Adalynn 1 Aalina 1 Abelaket 1 Adalynne 33 Aaliyah 2 Abella 1 Adan 1 Aaliyah-Jade 2 Abi 1 Adan-Rehman 1 Aalizah 1 Abiageal 1 Adara 1 Aalyiah 1 Abiela 3 Addalyn 1 Aamber 153 Abigail 2 Addalynn 1 Aamilah 1 Abigaille 1 Addalynne 1 Aamina 1 Abigail-Yonas 1 Addeline 1 Aaminah 3 Abigale 2 Addelynn 1 Aanvi 1 Abigayle 3 Addilyn 2 Aanya 1 Abiha 1 Addilynn 1 Aara 1 Abilene 66 Addison 1 Aaradhya 1 Abisha 3 Addisyn 1 Aaral 1 Abisola 1 Addy 1 Aaralyn 1 Abla 9 Addyson 1 Aaralynn 1 Abraj 1 Addyzen-Jerynne 1 Aarao 1 Abree 1 Adea 2 Aaravi 1 Abrianna 1 Adedoyin 1 Aarcy 4 Abrielle 1 Adela 2 Aaria 1 Abrienne 25 Adelaide 2 Aariah 1 Abril 1 Adelaya 1 Aarinya 1 Abrish 5 Adele 1 Aarmi 2 Absalat 1 Adeleine 2 Aarna 1 Abuk 1 Adelena 1 Aarnavi 1 Abyan 2 Adelin 1 Aaro 1 Acacia 5 Adelina 1 Aarohi 1 Acadia 35 Adeline 1 Aarshi 1 Acelee 1 Adéline 2 Aarushi 1 Acelyn 1 Adelita 1 Aarvi 2 Acelynn 1 Adeljine 8 Aarya 1 Aceshana 1 Adelle 2 Aaryahi 1 Achai 21 Adelyn 1 Aashvi 1 Achan 2 Adelyne 1 Aasiyah 1 Achankeng 12 Adelynn 1 Aavani 1 Achel 1 Aderinsola 1 Aaverie 1 Achok 1 Adetoni 4 Aavya 1 Achol 1 Adeyomola 1 Aayana 16 Ada 1 Adhel 2 Aayat 1 Adah 1 Adhvaytha 1 Aayath 1 Adahlia 1 Adilee 1 -

The Assumption of All Humanity in Saint Hilary of Poitiers' Tractatus Super Psalmos

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Dissertations (1934 -) Projects The Assumption of All Humanity in Saint Hilary of Poitiers' Tractatus super Psalmos Ellen Scully Marquette University Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu Part of the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Scully, Ellen, "The Assumption of All Humanity in Saint Hilary of Poitiers' Tractatus super Psalmos" (2011). Dissertations (1934 -). 95. https://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu/95 THE ASSUMPTION OF ALL HUMANITY IN SAINT HILARY OF POITIERS’ TRACTATUS SUPER PSALMOS by Ellen Scully A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Milwaukee, Wisconsin May 2011 ABTRACT THE ASSUMPTION OF ALL HUMANITY IN SAINT HILARY OF POITIERS’ TRACTATUS SUPER PSALMOS Ellen Scully Marquette University, 2011 In this dissertation, I focus on the soteriological understanding of the fourth- century theologian Hilary of Poitiers as manifested in his underappreciated Tractatus super Psalmos . Hilary offers an understanding of salvation in which Christ saves humanity by assuming every single person into his body in the incarnation. My dissertation contributes to scholarship on Hilary in two ways. First, I demonstrate that Hilary’s teaching concerning Christ’s assumption of all humanity is a unique development of Latin sources. Because of his understanding of Christ’s assumption of all humanity, Hilary, along with several Greek fathers, has been accused of heterodoxy resulting from Greek Platonic influence. I demonstrate that Hilary is not influenced by Platonism; rather, though his redemption model is unique among the early Latin fathers, he derives his theology from a combination of Latin-influenced biblical exegesis and classical Roman themes. -

Marriage Certificates

GROOM LAST NAME GROOM FIRST NAME BRIDE LAST NAME BRIDE FIRST NAME DATE PLACE Abbott Calvin Smerdon Dalkey Irene Mae Davies 8/22/1926 Batavia Abbott George William Winslow Genevieve M. 4/6/1920Alabama Abbotte Consalato Debale Angeline 10/01/192 Batavia Abell John P. Gilfillaus(?) Eleanor Rose 6/4/1928South Byron Abrahamson Henry Paul Fullerton Juanita Blanche 10/1/1931 Batavia Abrams Albert Skye Berusha 4/17/1916Akron, Erie Co. Acheson Harry Queal Margaret Laura 7/21/1933Batavia Acheson Herbert Robert Mcarthy Lydia Elizabeth 8/22/1934 Batavia Acker Clarence Merton Lathrop Fannie Irene 3/23/1929East Bethany Acker George Joseph Fulbrook Dorothy Elizabeth 5/4/1935 Batavia Ackerman Charles Marshall Brumsted Isabel Sara 9/7/1917 Batavia Ackerson Elmer Schwartz Elizabeth M. 2/26/1908Le Roy Ackerson Glen D. Mills Marjorie E. 02/06/1913 Oakfield Ackerson Raymond George Sherman Eleanora E. Amelia 10/25/1927 Batavia Ackert Daniel H. Fisher Catherine M. 08/08/1916 Oakfield Ackley Irving Amos Reid Elizabeth Helen 03/17/1926 Le Roy Acquisto Paul V. Happ Elsie L. 8/27/1925Niagara Falls, Niagara Co. Acton Robert Edward Derr Faith Emma 6/14/1913Brockport, Monroe Co. Adamowicz Ian Kizewicz Joseta 5/14/1917Batavia Adams Charles F. Morton Blanche C. 4/30/1908Le Roy Adams Edward Vice Jane 4/20/1908Batavia Adams Edward Albert Considine Mary 4/6/1920Batavia Adams Elmer Burrows Elsie M. 6/6/1911East Pembroke Adams Frank Leslie Miller Myrtle M. 02/22/1922 Brockport, Monroe Co. Adams George Lester Rebman Florence Evelyn 10/21/1926 Corfu Adams John Benjamin Ford Ada Edith 5/19/1920Batavia Adams Joseph Lawrence Fulton Mary Isabel 5/21/1927Batavia Adams Lawrence Leonard Boyd Amy Lillian 03/02/1918 Le Roy Adams Newton B. -

Spring 2021 Dean's List

Nashville State Community College Dean’s List Spring 2021 Elijah Joy Abat Spelanda Alexis Calen Arnold Alyssa Barnes Marina Abdelnour Ruqia Ali Timothy Arnold Desiree Barnhill Masi Abdoli Raghad Alkadi Jonathan Arroyo Shanna Barr Sharmeen Abdulah Henry Allard Shirgul Aryobi Sandy Baseet Dalya Abdullah Robert Allbert Amanda Asgari-Rad Cherry Ann Basiculan Ramzy Abdurzak Hannah Allen Obaid Ashari Eddy Basiluabo Rebekah Abraham Sierra Allen Joel Askew Candice Bass Genesis Abreu Abigail Allen Dina Attalla Kimberly Bateman Jose Acosta Julia Allen Danielle Aucoin Erin Bates Artemio Acosta Shannon Allen Andrew Awad Joseph Batson Brandi Adams Gabriel Allensworth Chase Aymett Emily Baucum Drew Adams John Allison Eman Ayoub Mackenzie Baumann Sydney Adams Grace Allison Bahija Aziz Annabelle Beamer Epiphanie Adams Rafan Alsabbagh B Cheyenne Beasley Lydia Adams Mohamed Alsafi Thomas Bacha Phillip Beasley Maegen Adkins Aqabal Alvarez Leaser Bacon John Beavin Skylar Adkins Mayer Alvarez Barrios Felo Dominic Justin Bagsic Jesse Beck Candice Aguilera Marielis Ametller Matalobos Nathan Bailey Zozan Beduhe Rukhsora Akhmadjonova Loren Amsbary Darius Baisden Ashley Beigert Randall Akin Isabella Anderson Diondre’ Baisden Magda Bekhit Mari Al Kanakri Shonta Anderson Carley Baker Tytionne Bellamy Farah Al Roome Al Taie Tammy Anderson Lucas Baker Armin Beni Omar Al Sharbati Amanda Andrews Cody Baker Reysalen Bernhoffer Sara Al-Ali Matthew Angel Joshua Baker Hari Bernstein Maryam Al-Zhyri Melissa Angevine Kelsey Baker Sara Bernstein Bayan Alamrani Stella Ann Lawrence -

Becoming Saints: Coptic Orthodox Monasticism, Exemplarity, & Negotiating Christian Virtue

Becoming Saints: Coptic Orthodox Monasticism, Exemplarity, & Negotiating Christian Virtue by Joseph Youssef A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology University of Toronto © Copyright by Joseph Youssef (2019) Becoming Saints: Coptic Orthodox Monasticism, Exemplarity, & Negotiating Christian Virtue Joseph Youssef Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology University of Toronto 2019 Abstract Based on 13 months of transnational ethnographic fieldwork between Egypt, Southern California, and Toronto, this dissertation examines questions around exemplarity, morality, and the cultivation of virtue among Coptic Orthodox Christians. Specifically, this thesis investigates the relationship between Coptic monks and the wider Coptic community. Many Copts view monasticism as a morally exemplary way of life. The monk as one who has forsaken all social ties and lives in the desert is regarded as one who has attained the highest form of virtue. This view results in different levels of engagement with monastic practice and competing voices for what it means to be a Coptic Christian. As will be demonstrated through ethnographic details, there is a gap between the ideals of the Coptic monastic imaginary and the lived reality of negotiating Christian virtue for monks and laity alike. Furthermore, this dissertation unpacks the ways in which Coptic monasticism is (re-)imagined and (re-)produced in North America and how Coptic subjectivity is (re-)negotiated in relation to Egypt and the Mother Church. ii Acknowledgments Becoming exemplary is a process as this dissertation will soon show. Whether one strives to be the best monk, Christian, or anthropologist, there are many along the path who are a part of this process, who challenge, encourage, and patiently watch for the individual to grow and formulate their vocation. -

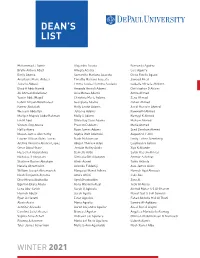

Winter 2021 Dean's List

DEAN’S LIST Mohammad J Aamir Alejandro Acosta Fernando Aguirre Brylle Altheia Abad Allegra Acosta Luis Aguirre Emily Abarca Samantha Mariano Acuesta Olivia Fidelis Aguzzi Anastasia Marie Abbasi Timothy Mariano Acuesta Jawaad Ahed Zakaria Abbasi Emma Louise Elomina Aculado Isabelle Mirielle Ahlborn Ehab A Abdelhamid Amanda Areceli Adame Christopher D Ahlers Ali Ahmed Abdellatief Asia Monea Adams Amna Ahmad Yassin AbdelMagid Christina Marie Adams Zena Ahmad Fahmi Amjad Abdulhafeez Georgiana Adams Zuhair Ahmad Kamar Abdullah Holly Leann Adams Aseal Hussein Ahmed Weseem Abdullah Julia Iva Adams Fawwad H Ahmed Mariyah Mujeeb AbdurRahman Molly G Adams Kumayl K Ahmed Ian M Abel Olivia Ray Case Adams Mahum Ahmed Vincent Ong Abella Preston D Adams Maria Ahmed Haffiz Abera Ryan James Adams Syed Zeeshan Ahmed Mason James Abernethy Sophia Wolf Adamski Augustine Y Ahn Lauren Allison Ables-Torres Noah M Adamson Emily Esther Aizenberg Andrea Veronica Abonce Lopez Abigail Therese Adan Luqmaan S Ajmeri Omar Aboul-Nasr Jordain Hailey Addis Xiya K Akande Hussein A Abourahma Danielle Addo Saleh Kasem Akhras Nicholas R Abraham Simisola Gift Adedunni Ammar A Akhtar Shalinee Rachel Abraham Almir Ademi Taiwo Akinola Natalia Abramovich Adenike F Adeniji Alex James Akins William Joseph Abramovich Marquise Monet Adkins Hannah Ayat Akroush Noah Benjamin Abrams Amira Afridi Jake Aks Dina Mousa Abuhadba Syed Aftaabuddin Zara Al Egerton Ekata Abulu Rafia Waseem Afzal Jude Al Abosy Lena Abu-Safieh Sarah O Agboola Ahmad Matar S S Al Ghanim Hannah Abuzir Sarah Agolia -

Catherine of Alexandria

Catherine of Alexandria “Katherine of Alexandria” redirects here. For the 2014 of the best pagan philosophers and orators to dispute with film, see Katherine of Alexandria (film). her, hoping that they would refute her pro-Christian ar- guments, but Catherine won the debate. Several of her Saint Catherine of Alexandria, also known as Saint adversaries, conquered by her eloquence, declared them- selves Christians and were at once put to death.[6] Catherine of the Wheel and The Great Martyr Saint Catherine (Greek: ἡ Ἁγία Αἰκατερίνα ἡ Μεγαλο- μάρτυς) is, according to tradition, a Christian saint and virgin, who was martyred in the early 4th century at the 1.1 Torture and martyrdom hands of the pagan emperor Maxentius. According to her hagiography, she was both a princess and a noted scholar, who became a Christian around the age of fourteen, and converted hundreds of people to Christianity. Over 1,100 years following her martyrdom, St. Joan of Arc identified Catherine as one of the Saints who appeared to her and counselled her.[3] The Orthodox Church venerates her as a Great Martyr, and celebrates her feast day on 24 or 25 November (de- pending on the local tradition). In the Catholic Church she is traditionally revered as one of the Fourteen Holy Helpers. In 1969 the Catholic Church removed her feast day from the General Roman Calendar;[4] however, she continued to be commemorated in the Roman Martyrol- ogy on November 25.[5] In 2002, her feast was restored to the General Roman Calendar as an optional memorial. 1 Life According to the traditional narrative, Catherine was the beautiful daughter of the pagan King Costus and Queen Sabinella, who governed Alexandria. -

Names Meanings

Name Language/Cultural Origin Inherent Meaning Spiritual Connotation A Aaron, Aaran, Aaren, Aarin, Aaronn, Aarron, Aron, Arran, Arron Hebrew Light Bringer Radiating God's Light Abbot, Abbott Aramaic Spiritual Leader Walks In Truth Abdiel, Abdeel, Abdeil Hebrew Servant of God Worshiper Abdul, Abdoul Middle Eastern Servant Humble Abel, Abell Hebrew Breath Life of God Abi, Abbey, Abbi, Abby Anglo-Saxon God's Will Secure in God Abia, Abiah Hebrew God Is My Father Child of God Abiel, Abielle Hebrew Child of God Heir of the Kingdom Abigail, Abbigayle, Abbigail, Abbygayle, Abigael, Abigale Hebrew My Farther Rejoices Cherished of God Abijah, Abija, Abiya, Abiyah Hebrew Will of God Eternal Abner, Ab, Avner Hebrew Enlightener Believer of Truth Abraham, Abe, Abrahim, Abram Hebrew Father of Nations Founder Abriel, Abrielle French Innocent Tenderhearted Ace, Acey, Acie Latin Unity One With the Father Acton, Akton Old English Oak-Tree Settlement Agreeable Ada, Adah, Adalee, Aida Hebrew Ornament One Who Adorns Adael, Adayel Hebrew God Is Witness Vindicated Adalia, Adala, Adalin, Adelyn Hebrew Honor Courageous Adam, Addam, Adem Hebrew Formed of Earth In God's Image Adara, Adair, Adaira Hebrew Exalted Worthy of Praise Adaya, Adaiah Hebrew God's Jewel Valuable Addi, Addy Hebrew My Witness Chosen Addison, Adison, Adisson Old English Son of Adam In God's Image Adleaide, Addey, Addie Old German Joyful Spirit of Joy Adeline, Adalina, Adella, Adelle, Adelynn Old German Noble Under God's Guidance Adia, Adiah African Gift Gift of Glory Adiel, Addiel, Addielle -

Civil War Manuscripts

CIVIL WAR MANUSCRIPTS CIVIL WAR MANUSCRIPTS MANUSCRIPT READING ROW '•'" -"•••-' -'- J+l. MANUSCRIPT READING ROOM CIVIL WAR MANUSCRIPTS A Guide to Collections in the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress Compiled by John R. Sellers LIBRARY OF CONGRESS WASHINGTON 1986 Cover: Ulysses S. Grant Title page: Benjamin F. Butler, Montgomery C. Meigs, Joseph Hooker, and David D. Porter Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Library of Congress. Manuscript Division. Civil War manuscripts. Includes index. Supt. of Docs, no.: LC 42:C49 1. United States—History—Civil War, 1861-1865— Manuscripts—Catalogs. 2. United States—History— Civil War, 1861-1865—Sources—Bibliography—Catalogs. 3. Library of Congress. Manuscript Division—Catalogs. I. Sellers, John R. II. Title. Z1242.L48 1986 [E468] 016.9737 81-607105 ISBN 0-8444-0381-4 The portraits in this guide were reproduced from a photograph album in the James Wadsworth family papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress. The album contains nearly 200 original photographs (numbered sequentially at the top), most of which were autographed by their subjects. The photo- graphs were collected by John Hay, an author and statesman who was Lin- coln's private secretary from 1860 to 1865. For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402. PREFACE To Abraham Lincoln, the Civil War was essentially a people's contest over the maintenance of a government dedi- cated to the elevation of man and the right of every citizen to an unfettered start in the race of life. President Lincoln believed that most Americans understood this, for he liked to boast that while large numbers of Army and Navy officers had resigned their commissions to take up arms against the government, not one common soldier or sailor was known to have deserted his post to fight for the Confederacy.