Tackling the Problem of Youth Unemployment in Denmark

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oversigt Over Retskredsnumre

Oversigt over retskredsnumre I forbindelse med retskredsreformen, der trådte i kraft den 1. januar 2007, ændredes retskredsenes numre. Retskredsnummeret er det samme som myndighedskoden på www.tinglysning.dk. De nye retskredsnumre er følgende: Retskreds nr. 1 – Retten i Hjørring Retskreds nr. 2 – Retten i Aalborg Retskreds nr. 3 – Retten i Randers Retskreds nr. 4 – Retten i Aarhus Retskreds nr. 5 – Retten i Viborg Retskreds nr. 6 – Retten i Holstebro Retskreds nr. 7 – Retten i Herning Retskreds nr. 8 – Retten i Horsens Retskreds nr. 9 – Retten i Kolding Retskreds nr. 10 – Retten i Esbjerg Retskreds nr. 11 – Retten i Sønderborg Retskreds nr. 12 – Retten i Odense Retskreds nr. 13 – Retten i Svendborg Retskreds nr. 14 – Retten i Nykøbing Falster Retskreds nr. 15 – Retten i Næstved Retskreds nr. 16 – Retten i Holbæk Retskreds nr. 17 – Retten i Roskilde Retskreds nr. 18 – Retten i Hillerød Retskreds nr. 19 – Retten i Helsingør Retskreds nr. 20 – Retten i Lyngby Retskreds nr. 21 – Retten i Glostrup Retskreds nr. 22 – Retten på Frederiksberg Retskreds nr. 23 – Københavns Byret Retskreds nr. 24 – Retten på Bornholm Indtil 1. januar 2007 havde retskredsene følende numre: Retskreds nr. 1 – Københavns Byret Retskreds nr. 2 – Retten på Frederiksberg Retskreds nr. 3 – Retten i Gentofte Retskreds nr. 4 – Retten i Lyngby Retskreds nr. 5 – Retten i Gladsaxe Retskreds nr. 6 – Retten i Ballerup Retskreds nr. 7 – Retten i Hvidovre Retskreds nr. 8 – Retten i Rødovre Retskreds nr. 9 – Retten i Glostrup Retskreds nr. 10 – Retten i Brøndbyerne Retskreds nr. 11 – Retten i Taastrup Retskreds nr. 12 – Retten i Tårnby Retskreds nr. 13 – Retten i Helsingør Retskreds nr. -

Delo Ehf Champions League 2020/21

MEDIA INFORMATION DELO EHF CHAMPIONS LEAGUE 2020/21 MOTW Round 8: Team Esbjerg vs Rostov-Don TEAM ESBJERG (DEN) VS ROSTOV-DON (RUS) GROUP A Sunday 15 November 2020, 14:00 CET ROUND 8 Playing hall Blue Water Dokken Gammel Vardevej 82 6700 Esbjerg Denmark Capacity: 2,949 • Rostov-Don defeated Team Esbjerg 28:24 last week Most games vs Rostov-Don: in round 7 of the DELO EHF Champions League. Most games vs Team Esbjerg: • Both teams missed their No. 1 goalkeeper last week: Kristine Breistøl 3 Mayssa Pessoa (Rostov) and Rikke Poulsen (Esbjerg). Vladlena Bobrovnikova 5 Marit Malm Frafjord 3 Anna Sen 5 • Mette Tranborg is Esbjerg's best scorer so far with 33 Sonja Frey 3 goals; Anna Vyakhireva leads for Rostov with 28. Galina Gabisova 4 Rikke Marie Granlund 3 Marina Sudakova 4 Elma Halicevic 3 • Rostov’s Swedish line player Anna Lagerquist played Viktoriya Borshchenko 3 Marit Røsberg Jacobsen 3 in Denmark for the past three seasons, for Nykøbing. Regina Kalinichenko 3 Sanna Solberg-Isaksen 3 • Rostov's squad includes five Russian 2016 Olympic Kristina Kozhokar 3 champions (Viktoriia Kalinina, Anna Vyakhireva, Anna Iuliia Managarova 3 Sen, Vladlena Bobrovnikova, Polina Kuznetsova), one Most goals vs Rostov-Don: French EHF EURO 2018 champion (Grace Zaadi), and one Brazilian world champion from 2013 (Mayssa Pessoa). Most goals vs Team Esbjerg: Lotte Grigel 20 • Esbjerg line player Marit Malm Frafjord has won Sonja Frey 16 the EHF EURO (2006, 2008, 2010, 2016), the World Regina Kalinichenko 23 Championship (2011) and the Olympic Games (2008, Sanna Solberg-Isaksen 15 2012) with the Norwegian national team. -

Odense – a City with Water Issues Urban Hydrology Involves Many Different Aspects

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Available online at www.sciencedirect.com 2 Laursen et al./ Procedia Engineering 00 (2017) 000–000 Procedia Engineering 00 (2017) 000–000 www.elsevier.com/locate/procedia ScienceDirect underground specialists on one side and the surface planners, decision makers and politicians on the other. There is a strong need 2for positive interaction and sharing of knowledgeLaursen et al./ between Procedia all Engineering involved parties. 00 (2017) It is000–000 important to acknowledge the given natural Procedia Engineering 209 (2017) 104–118 conditions and work closely together to develop a smarter city, preventing one solution causing even greater problems for other parties. underground specialists on one side and the surface planners, decision makers and politicians on the other. There is a strong need forKeyword positive: Abstraction; interaction groundwater; and sharing climate of knowledge change; city between planning; all exponential involved parties.growth; excessiveIt is important water to acknowledge the given natural Urban Subsurface Planning and Management Week, SUB-URBAN 2017, 13-16 March 2017, conditions and work closely together to develop a smarter city, preventing one solution causing even greater problems for other parties. Bucharest, Romania Keyword1. Introduction: Abstraction; and groundwater; background climate change; city planning; exponential growth; excessive water Odense – A City with Water Issues Urban hydrology involves many different aspects. In our daily work as geologists at the municipality and the local water1. Introduction supply, it isand rather background difficult to “force” city planners, decision makers and politicians to draw attention to “the a b* Underground”. Gert Laursen and Johan Linderberg RegardingUrban hydrology the translation involves many and differentcommunication aspects. -

PRESS ACCREDITATION for ROYAL RUN, May 21St 2018 Royal

PRESS ACCREDITATION FOR ROYAL RUN, May 21st 2018 HRH The Crown Prince turns 50 on May 26th 2018. The birthday will be marked with a weeklong celebration starting on May 21st with Royal Run, a big running event taking place in Denmark’s five largest cities. Royal Run will take place in Aalborg, Aarhus, Esbjerg, Odense and Copenhagen where Danes are invited to participate in a One mile (1,609 Km) or a 10k run. The Crown Prince will run the One mile distance in the first four cities and finish with a 10k run in Copenhagen. Royal Run is organised by The National Olympic Committee & Sports Confederation of Denmark, DGI and the Danish Athletic Federation as part of “Move for Life”, which is the shared vision to make Denmark the most active nation in the world. A vision, which is supported by Nordea-Fonden and TrygFonden. The Crown Prince is protector of “Move for Life”. In order for the press to cover the event, accreditation is needed. The accreditation provides access to the press and photo positions for accredited media only. Only journalists and photographers with a documented working relation to a specific media will be granted accreditation. Freelancers need to document their assignment of the covering of the Royal Run with an acknowledged media. The press is invited to cover the event in one or more Royal Run cities. AALBORG: Aalborg Press Center opens at 08:00. Address: Utzon Centret, Slotspladsen 4, 9000 Aalborg. 8.15: Briefing of accredited photographers and journalists, including access to media areas etc. -

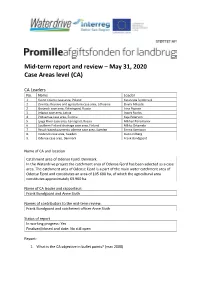

Midterm Case Area Denmark

Mid-term report and review – May 31, 2020 Case Areas level (CA) CA Leaders No. Name Leader 1. Kutno County case area, Poland Katarzyna Izydorczyk 2. Zuvintas Reserve and agriculture case area, Lithuania Elvyra Miksyte 2. Gurjevsk case area, Kaliningrad, Russia Irina Popova 3. Jelgava case area, Latvia Ingars Rozitis 4. Pöltsamaa case area, Estonia Kaja Peterson 5. Ljuga River case area, Leningrad, Russia Mikhail Ponomarev 6. Southern Finland drainage case area, Finland Mikko Ortamala 7. Result-based payments scheme case area, Sweden Emma Svensson 8. Västervik case area, Sweden Gun Lindberg 9. Odense case area, Denmark Frank Bondgaard Name of CA and location Catchment area of Odense Fjord. Denmark. In the Waterdrive project the catchment area of Odense Fjord has been selected as a case area. The catchment area of Odense Fjord is a part of the main water catchment area of Odense Fjord and constitutes an area of 105.600 ha, of which the agricultural area constitutes approximately 63.960 ha. Name of CA leader and rapporteur: Frank Bondgaard and Anne Sloth Names of contributors to the mid-term review: Frank Bondgaard and catchment officer Anne Sloth Status of report In working progress: Yes Finalized/closed and date: No still open Report: 1. What is the CA objective in bullet points? (max 2000) 1. Increase rural cooperation on targeted water management solutions that go hand in hand with efficient agricultural production. 2. Test instruments/tools to strengthen leadership and capacity building among the water management target groups. 3. Secure local cross-sector cooperation. 4. Find out how agriculture's environmental advisors/catchment officers best can work in a clear and coordinated way with the local authorities, agricultural companies and the local community. -

Klaptilladelse Til: Bregnør Havn

Kerteminde Kommune Vandplaner og havmiljø Hans Schacksvej 4 J.nr. NST-4311-00124 5300 Kerteminde Ref. CGRUB CVR: 29 18 97 06 Den 30. juni 2015 Att.: Lars Bertelsen Mail: [email protected] Tlf: 65 15 14 61 Klaptilladelse til: Bregnør Havn. Tilladelsen omfatter: Naturstyrelsen meddeler hermed en 5-årig tilladelse til klapning af 2.500m3 havbundsmateriale fra indsejlingen til Bregnør Havn1. Klapningen skal foregå på klapplads Gabet (K_088_01). Oversigt over havnen og den anviste klapplads. Annonceres den 30. juni 2015 på Naturstyrelsens hjemmeside www.naturstyrelsen.dk/Annonceringer/Klaptilladelser/. Tilladelsen må ikke udnyttes før klagefristen er udløbet. Klagefristen udløber den 28. juli 2015. Tilladelsen er gældende til og med den 1. august 2020. 1 Tilladelsen er givet med hjemmel i havmiljølovens § 26, jf. lovbekendtgørelse nr. 963 af 3. juli 2013 af lov om beskyttelse af havmiljøet. Naturstyrelsen • Haraldsgade 53 • 2100 København Ø Tlf. 72 54 30 00 • Fax 39 27 98 99 • CVR 33157274 • EAN 5798000873100 • [email protected] • www.nst.dk Indholdsfortegnelse 1. Vilkår for klaptilladelsen .............................................................. 3 1.1 Vilkår for optagning og brugen af klappladsen ........................ 3 1.2 Vilkår for indberetning .................................................................. 3 1.3 Vilkår for tilsyn og kontrol ............................................................ 4 2. Oplysninger i sagen ..................................................................... 5 2.1 Baggrund for ansøgningen ........................................................ -

Regulativ for Gudenåen Silkeborg - Randers 2000 Regulativ for Gudenåen Silkeborg - Randers 2000

Regulativ for Gudenåen Silkeborg - Randers 2000 Regulativ for Gudenåen Silkeborg - Randers 2000 Viborg Amtsvandløb nr.: O 10 km 20 105 i Viborg amt 78 i Århus amt Indholdsfortegnelse side Forord 4 1. Grundlag for regulativet 5 2. Vandløbet 6 2. l Beliggenhed 6 2.2 Opmåling 6 2.3 Afmærkning 7 3. Vandløbets strækninger, vandføringsevne og dimensioner 9 3.1 Strækningsoversigt 9 3.2 Vandføringsevne 9 3.3 Dimensioner 10 4. Bygværker og tilløb. 12 4.1 Broer 12 4.2 Opstemningsanlæg 13 4.3 Andre bygværker 14 4.4 Større åbne tilløb 15 5. Administrative bestemmelser 16 5.1 Administration 16 5.2 Bygværker 16 5.3 Trækstien 17 6. Bestemmelser for sejlads 18 6.1 Generelt 18 6.2. Ikke - erhvervsmæssig sejlads 18 6.2. l Ikke - erhvervsmæssig sejlads på Tange Sø 18 6.3 Erhvervsmæssig sejlads 18 7. Bredejerforhold 19 7.1 Banketter 19 7.2 Arbejdsbælte langs vandløbet 19 7.3 Hegning 19 7.4 Ændring af vandløbets tilstand 19 7.5 Reguleringer m.m. 19 7.6 Forureninger m.v. 19 7.7 Drænudløb og grøfter 20 7.8 Skade på bygværker 20 7.9 Vandindvinding m.m. 20 7.10 Overtrædelse af bestemmelserne 20 8.1.1 Særbidrag 21 8.2 Oprensning 21 8.3 Grødeskæring 22 8.4 Kantskæring 22 8.5 Oprenset bundmateriale 22 9. Tilsyn 23 10. Revision 23 11. Regulativets ikrafttræden 23 Forord Dette regulativ er retsgrundlaget for administrationen af amtsvandløbet Gudenåen på strækningen mellem Silkeborg og Randers. Det indeholder bestemmelser om vandløbets fysiske udseende, vedligeholdelse samt de respektive amtsråds og lodsejeres forpligtelser og rettigheder ved vandløbet, og er derfor af stor betydning for såvel de afoandingsmæssige forhold som miljøet i og ved vandløbet. -

6-Benet Rundkørsel I Kolding Vest

6-benet Rundkørsel i Kolding Vest Undersøgelse af trafikanternes samspilsadfærd i ny 2-sporet rundkørsel Belinda la Cour Lund 7. September 2014 Trafitec Scion-DTU Diplomvej 376 2800 Kgs. Lyngby www.trafitec.dk 6-benet rundkørsel i Kolding. Undersøgelse af trafikanternes samspilsadfærd i 2-sporet rundkørsel Trafitec Indhold 1 Indledning ............................................................................................................ 3 2 Adfærdsundersøgelse ......................................................................................... 4 2.1 Rundkørselsgeometri ..................................................................................... 4 2.2 Adfærdsregistrering af hvert af de seks rundkørselsben................................ 5 2.3 Opsamling af konfliktende adfærd og samspilsadfærd ............................... 15 BILAG 1 Afmærkningsplan ............................................................................... 17 2 6-benet rundkørsel i Kolding. Undersøgelse af trafikanternes samspilsadfærd i 2-sporet rundkørsel Trafitec 1 Indledning Dette notat indeholder en adfærdsanalyse af en ny 6-benet rundkørsel ved Kolding Vest, ved frakørsel <64> på den Sønderjyske Motorvej. Rundkørslen er 2-sporet og har en ø-diameter på 110 m. Rundkørslen blev taget i brug i juni 2013, og har således været i brug i et år. Selvom der det første år efter ibrugtagning hverken er registreret ulykker eller anden uhensigtsmæssig kørsel, ved man af erfaring, at det kan være svært for tra- fikanter at navigere i store 2-sporede rundkørsler. -

Intercity Og Intercitylyn 06.01.2008-10.01.2009

InterCity og InterCityLyn 06.01.2008-10.01.2009 Frederikshavn Thisted Aalborg Struer Viborg Herning Århus H Roskilde København Kolding Ringsted Kbh.s Lufthavn, Esbjerg Odense Kastrup Sønderborg Padborg Rejser med InterCity og InterCityLyn Indhold Plan Side Frederikshavn 6 Tegnforklaring 4 7 1 Sådan bruger du køreplanen 6 Thisted Aalborg Hvor lang tid skal du bruge til at skifte tog? 8 Vigtigste ændringer for køreplanen 10 Struer 2 Sporarbejder medfører ændringer 10 Viborg Århus 3 2 6 7 1 Trafikinformation 11 Herning Pladsreservation 12 Vejle København H Middelfart Odense 2 10 2 Rejsetidsgaranti 13 Esbjerg 3 3 6 1 1 4 4 4 Ystad Køb af billet 13 5 5 Kbh./ Kastrup Rønne 10 Røgfri tog 13 Sønderborg 7 1 København - Frederikshavn 14 5 Padborg 5 7 2 København - Århus - Struer 38 3 København - Herning - Struer - Thisted 48 Sådan bruges kortet 4 København - Esbjerg 56 Numrene på kortene viser, i hvilken køreplan du bedst 5 København - Sønderborg/Padborg 68 kan finde din rejse mellem to stationer. 6 Frederikshavn - Århus - Esbjerg 76 7 Frederikshavn - Sønderborg/Padborg 88 Hvis begge stationer ligger på en rød del af linjen, kan du finde alle rejser mellem de to stationer i den køreplan, 10 København - Ystad/Bornholm 100 der er vist ved linjen. Rejser og helligdage 108 Hvis den ene station ligger på den røde del og den Kalender 109 anden station ligger på den grå del af samme linje, viser køreplanen alle rejser til og fra den station, der ligger på den røde del af linjen. Opdateret den 17. jan 2008 Tryk Nørhaven Paperback A/S Udgivet af: DSB tager forbehold for trykfejl og ændringer i Hvis begge stationer ligger på den grå del af linjen, DSB Planlægning og Trafik køreplanerne. -

Odense Harbour Mussel Project Report

Report on Odense Harbour Mussel Project – September 2015 A pilot study to assess the feasibility of cleaning sea water in Odense harbour by means of filter-feeding blue mussels on suspended rope nets Florian Lüskow – Baojun Tang – Hans Ulrik Riisgård Marine Biological Research Centre, University of Southern Denmark, Hindsholmvej 11, DK-5300 Kerteminde, Denmark ___________________________________________________________________________ SUMMARY: The Odense Kommune initiated in May 2015 a five month long pilot study to evaluate the feasibility of bio-filtering blue mussels to clean the heavily eutrophicated water in the harbour of Odense and called for meetings with NordShell and the University of Southern Denmark. Over a period of 16 weeks the environmental conditions, mussel offspring, growth, and filtration capacity was investigated on a weekly basis. The results of the present pilot study show that the growth conditions for mussels in Odense harbour are reasonably good. Thus, the weight-specific growth rates of transplanted mussels in net-bags are comparable to other marine areas, such as the Great Belt and Limfjorden. Even if the chlorophyll a concentration is 5 to 10 times higher than the Chl a concentration in the reference station in the Kerteminde Fjord mussels do not grow with a factor of 5 to 10 faster. Changing salinities, which might influence the growth of mussels to a minor degree, rarely fall below the critical value of 10. The natural recruitment of the local mussel population which is mainly located up to 2 m below the water surface is sufficient for rope farming, and natural thinning of densely populated ropes leads to densities between 20 to 56 ind. -

Mental Health and Safety at Aalborg University, Denmark

Mental health and safety at Aalborg University, Denmark In Denmark, your health issues should usually be directed towards your GP. In special cases like assault or sexual assault, you should contact the police who will assist you to medical treatment. Outside your GP’s opening hours, you can contact the on-call GP, whose phone number will be provided upon calling your GP, or you can find it on www.lægevagten.dk In case of acute emergency, call 112. In our Survival Guide, attached above, you can find additional information regarding health and safety on pages 21-24. Local Police Department Information Campus Aalborg Nordjyllands Politi (The Northern Jutland Police Department). Tel: +45 96301448. In case of emergency: 114. Address: Jyllandsgade 27, 9000 Aalborg Campus Esbjerg Syd- og Sønderjyllands Politi Kirkegade 76 6700 Esbjerg Tel:+45 76111448 Campus Copenhagen Københavns Politi Polititorvet 14 1567 København V Tel:+45 3314 1448 Dean of Students Information We do not have deans of students. If students experience abusive behavior or witness it, they can turn to the university's central student guidance: AAU STUDENT GUIDANCE: Phone: +45 99 40 94 40 (Monday-Friday from 12-15) Mail: [email protected] https://www.en.aau.dk/education/student-guidance/guidance/personal-issues/ https://www.en.aau.dk/education/student-guidance/guidance/offensive-behaviour/ Students are also encouraged to contact an employee in their educational environment if they are more comfortable with that. All employees who receive inquiries about abusive behavior from students must ensure that the case is handled properly. Advice and help on how to handle specific cases can be obtained by contacting the central student guidance on the above contact information. -

An Immigrant Story

THE DANISH IMMIGRANT MUSEUM - AN INTERNATIONAL CULTURAL CENTER Activity book An Immigrant Story The story of Jens Jensen and his journey to America in 1910. The Danish Immigrant Museum 2212 Washington Street Elk Horn, Iowa 51531 712-764-7001 www.danishmuseum.org 1 Name of traveler This is Denmark. From here you start your journey as an emigrant towards America. Denmark is a country in Scandinavia which is in the northern part of Europe. It is a very small country only 1/3 the size of the state of Iowa. It is made up of one peninsula called Jutland and 483 islands so the seaside is never far away. In Denmark the money is called kroner and everyone speaks Danish. The capital is called Copenhagen and is home to Denmark’s Royal Family and Parliament. The Danish royal family is the oldest in Europe. It goes all the way back to the Viking period. Many famous people have come from Denmark including Hans Christian Andersen who wrote The Little Mermaid. He was born in Odense and moved to Copenhagen. The Danish Immigrant Museum 2212 Washington Street Elk Horn, Iowa 51531 712-764-7001 www.danishmuseum.org Can you draw a line from Odense to Copenhagen? Did he have to cross the water to get there? 2 This is Jens Jensen. He lived in Denmark on a farm in 1910. That was a little over a hundred years ago. You can color him in. In 1910 Denmark looked much like it does today except that most people were farmers; they would grow wheat and rye, and raise pigs and cows.