An Evaluationevaluation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aasif Mandvi, Actor, Writer, Correspondent for the Daily Show

Aasif Mandvi, Actor, Writer, Correspondent for The Daily Show Aasif Mandvi is widely known for his work as a correspondent on Comedy Central’s The Daily Show with John Stewart. Also a renowned theater actor, Mandvi starred in the critically acclaimed production of Ayad Akhtar’s play Disgraced at Lincoln Center. Mandvi’s recent work includes The Internship (2013), wherein he stars alongside Will Ferrell, Owen Wilson, and Vince Vaughn. His other upcoming projects include Million Dollar Arm alongside John Hamm. Mandvi is the recipient of the 1999 OBIE Award for his critically acclaimed play Sakina’s Restaurant. Mandvi both performed and conceived this one- man show, which later became the inspiration for his feature film Today’s Special. Additional New York stage credits include the Broadway revival of Oklahoma, directed by Trevor Nunn, Homebody/Kabul by Tony Kushner, subUrbia by Eric Bogosian, and Trudy Blue by Marcia Norman. Mandvi’s film credits include M Night Shyamalan's The Last Airbender, Merchant/Ivory’s The Mystic Masseur, The Proposal with Sandra Bullock, Ghost Town with Ricky Gervais, Music and Lyrics with Hugh Grant and Drew Barrymore, Spiderman 2, Freedomland, The Siege, and Analyze This. Additional feature film credits include It’s Kind of a Funny Story, Ruby Sparks, Premium Rush and Margin Call. Aasif has a recurring role on the new FOX show Us & Them. Notable television credits include Curb Your Enthusiasm, Sex and the City, Sleeper Cell, The Sopranos, The Bedford Diaries, Oz, CSI, Law & Order, and Tanner on Tanner, directed by Robert Altman. He is also known for recurring roles on Jericho and ER. -

CAST BIOGRAPHIES Season 2 RICKY WHITTLE

CAST BIOGRAPHIES Season 2 RICKY WHITTLE (SHADOW MOON) Ricky Whittle was born in Oldham, near Manchester in the north of England. Growing up, Whittle excelled in various sports representing his country at youth level in football, rugby, American football and athletics. After being scouted by both Arsenal and Celtic Football Clubs, injuries forced him to pursue a law degree at Southampton University. It was here he began modeling, becoming the face of a Reebok campaign in 2000. Whittle left university to pursue an acting career and soon joined several action-packed seasons as bad boy Ryan Naysmith in Sky One’s “Dream Team.” Following that, Whittle quickly joined the U.K.’s hugely popular long-running drama, “Hollyoaks,” in which he played rookie cop Calvin Valentine to acclaim across 400+ episodes. In 2010, Whittle made the decision to relocate to California and, within months of settling in, booked the role of Captain George East in the romantic-comedy feature Austenland for Sony Pictures, which was produced by Twilight creator Stephanie Meyer. Additionally, he was soon cast in a major recurring role in VH1’s popular series, “Single Ladies.” Another major recurring role followed on The CW’s popular post-apocalyptic sci-fi series “The 100.” Whittle’s character, Lincoln, immediately became a fan-favorite character, so he was upped to a series regular. Simultaneously, Whittle also had a recurring arc as Daniel Zamora in ABC’s “Mistresses.” In 2016, after a vigorous casting process, Whittle won the coveted role of Shadow Moon in Starz’s “American Gods.” In 2017, Whittle was seen opposite Sanaa Lathan in the Netflix feature film Nappily Ever After, which is based on the novel of the same name by Trisha R. -

John Oliver, Burkean Frames, and the Performance of Public Intellect Gabriel Francis Nott Bates College, [email protected]

Bates College SCARAB Honors Theses Capstone Projects 5-2017 Not a Laughing Matter: John Oliver, Burkean Frames, and the Performance of Public Intellect Gabriel Francis Nott Bates College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scarab.bates.edu/honorstheses Recommended Citation Nott, Gabriel Francis, "Not a Laughing Matter: John Oliver, Burkean Frames, and the Performance of Public Intellect" (2017). Honors Theses. 198. http://scarab.bates.edu/honorstheses/198 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Capstone Projects at SCARAB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of SCARAB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nott 1 Not a Laughing Matter: John Oliver, Burkean Frames, and the Performance of Public Intellect An Honors Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Rhetoric Bates College In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts By Gabriel Nott Lewiston, Maine March 24, 2017 Nott 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 “Our Main Story Tonight Is…”: Introducing John Oliver 4 The Men Behind the Desk: A History of the Political Comedy News Host 10 Watching the Watchers: A Review of Existing Literature 33 Burkean Frames: A Theoretical Foundation 43 Laughing and Learning: John Oliver’s Comic Performance of Public Intellect 63 John Oliver and the Performance of Public Intellect 65 John Oliver, the Comic Comic 70 Oliver vs. the Walking, Talking Brush Fire 78 Oliver’s Barrier 84 John Oliver and the News Media 86 “That’s Our Show”: John Oliver and the Future of Civic Discourse 89 Works Cited 92 Nott 3 Acknowledgements Though mine is the only name appearing on the cover page of this thesis, it would be folly on my part not to acknowledge that this work is the product of the efforts of many people other than myself, a fact for which I am endlessly grateful. -

Seite 6 Episodensynopsen

INHALT CREDITS – SEITE 2 SYNOPSIS – SEITE 6 EPISODENSYNOPSEN – SEITE 7 SPOILER-LISTE – SEITE 9 FIGURENBESCHREIBUNGEN – SEITE 10 ÜBER DIE PRODUKTION – SEITE 13 BIOGRAFIEN DER HAUPTDARSTELLER – SEITE 21 BIOGRAFIEN WEITERER DARSTELLER – SEITE 30 BIOGRAFIEN DER SERIENMACHER – SEITE 35 KONTAKT LEWIS Communications [email protected] Tel.: 089 - 17301956 1 IN DEN HAUPTROLLEN Ricky Whittle Shadow Moon Ian McShane Mr. Wednesday Emily Browning Laura Moon Pablo Schreiber Mad Sweeney Crispin Glover Mr. World Orlando Jones Mr. Nancy Yetide Badaki Bilquis Bruce Langley Technical Boy Mousa Kraish The Jinn Omid Abtahi Salim Demore Barnes Mr. Ibis WEITERE ROLLEN Peter Stormare Czernobog Cloris Leachman Zorya Vechernyaya Kahyun Kim New Media Devery Jacobs Sam Black Crow Sakina Jaffrey Mama-Ji Dean Winters Mr. Town 2 AUF BASIS EINES ROMANS VON NEIL GAIMAN EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Jesse Alexander Neil Gaiman Craig Cegielski Scott Hornbacher Ian McShane Stefanie Berk Padraic McKinley Christopher J. Byrne CO-EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Heather Bellson Rodney Barnes SUPERVISING PRODUCER Adria Lang PRODUZENTEN Lisa Kussner BERATENDE PRODUZENTEN Peter Calloway Orlando Jones KAMERA Tico Poulakakis David Greene Marc Laliberté Else PRODUKTIONSDESIGNER Rory Cheyne CASTING-DIREKTOREN Debra Zane Jason Knight (CAN) KOSTÜMBILDNER Claire Anderson Robert Blackman MASKE Colin Penman STYLING Daniel Curet 3 STUNT-KOORDINATOR Layton Morrison SENIOR VISUAL EFFECTS SUPERVISOR Eric J. Robertson VISUAL EFFECTS SUPERVISOR Chris MacLean REDAKTEURE Wendy Hallam Martin Christopher Donaldson Don Cassidy TON Tyler Whitham REGIE (201) Christopher J. Byrne AUTOREN (201) Jesse Alexander Neil Gaiman REGIE (202) Frederick E.O. Toye AUTOREN (202) Tyler Dinucci Andres Fischer-Centeno REGIE (203) Deborah Chow AUTOR (203) Heather Bellson REGIE (204) Stacie Passon AUTOREN (204) Peter Calloway Aditi Brennan Kapil REGIE (205) Salli Richardson-Whitfield 4 AUTOR (205) Rodney Barnes REGIE (206) Rachel Talalay AUTOR (206) Adria Lang REGIE (207) Paco Cabezas AUTOR (207) Heather Bellson REGIE (208) Christopher J. -

Lisa Robinson & Annie J. Howell

A SACHA PICTURES PRODUCTION, IN ASSOCIATION WITH RUNNING MAN CLAIRE IN MOTION WRITTEN AND DIRECTED BY LISA ROBINSON & ANNIE J. HOWELL 2016 | USA | English | Drama | 80 min | HD 2:35 | Dolby 5.1 Sales Contact: Publicity Contact: Indie-PR / Jim Dobson [email protected] 173 Richardson Street, Brooklyn, NY 11222 USA Office: +1.718.312.8210 Fax: +1.718.362.4865 Email: [email protected] Web: www.visitfilms.com LOGLINE When Claire’s search for her missing husband leads her to an alluring and manipulative graduate student, she uncovers a world of secrets that threaten to shatter their family. SHORT SYNOPSIS Three weeks after Claire’s husband has mysteriously disappeared, the police have ended their investigation and her son is beginning to grieve. The only person who hasn’t given up is Claire. Soon she discovers his troubling secrets, including an alluring yet manipulative graduate student with whom he had formed a close bond. As she digs deeper, Claire begins to lose her grip on how well she truly knew her husband and questions her own identity in the process. Claire in Motion twists the missing person thriller into an emotional take on uncertainty and loss. TECH SPECS Run Time: 80 min Aspect Ratio: 2.35 Shooting Format: HD Sound: Dolby 5.1 Country: USA Language: English WEBSITE FACEBOOK TWITTER DIRECTORS’ STATEMENT With this film, we were interested in telling a story about something that’s been lost — both physically and spiritually. It was intriguing to give Claire a life crisis that leads to a bigger mystery, one that unravels her perception of all she knows to be true. -

RUSSIAN WORLD VISION Russian Content Distributor Russian World Vision Signed an Inter- National Distribution Deal with Russian Film Company Enjoy Movies

CISCONTENT:CONTENTRREPORTEPORT C ReviewОбзор of новостейaudiovisual рынка content производства production and и дистрибуции distribution аудиовизуальногоin the CIS countries контента Media«»«МЕДИ ResourcesА РЕСУРСЫ МManagementЕНЕДЖМЕНТ» №11№ 1(9) February №213 января, 1 April, 22, 20132011 2012 тема FOCUSномера DEARслово COLLEAGUES редакции WeУже are в happyпервые to presentдни нового you the года February нам, issue редак ofц theии greatПервый joy itномер appeared Content that stillReport there выходит are directors в кану whoн КИНОТЕАТРАЛЬНЫ Й CISContent Content Report, Report сразу where стало we triedпонятно, to gather что в the 2011 mostм treatСтарого film industryНового as года, an art который rather than (наконецто) a business за все мы будем усердно и неустанно трудиться. За вершает череду праздников, поэтому еще раз РЫНTVО КMARKETS В УКРАИН Е : interesting up-to-date information about rapidly de- velopingнимаясь contentподготовкой production первого and выпуска distribution обзора markets но хотим пожелать нашим подписчикам в 2011 ЦИФРОВИЗАЦИ Я КА К востей рынка производства и аудиовизуального годуAnd one найти more свой thing верный we’d likeпуть to и remindследовать you. емуPlan с- IN TAJIKISTAN, of the CIS region. As far as most of the locally pro- ning you business calendar for 2013 do not forget to ducedконтента series в этом and год TVу ,movies мы с радостью are further обнаружили distributed, упорством, трудясь не покладая рук. У каждого UZBEKISTAN,ОСНОВНОЙ ТРЕН ANDД что даже в новогодние праздники работа во мно свояbook timeдорога, to visit но theцель major у нас event одн forа – televisionразвивать and и and broadcast mainly inside the CIS territories, we media professionals in the CIS region - KIEV MEDIA РАЗВИТИ Я (25) pickedгих продакшнах up the most идет interesting полным хо andдом, original а дальше, projects как улучшать отечественный рынок. -

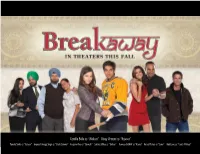

Vinay Virmani As

Camilla Belle as “Melissa” Vinay Virmani as “Rajveer” Pamela Sinha as “Jasleen” Gurpreet Ghuggi Singh as “Uncle Sammy” Anupam Kher as “Darvesh” Sakina Jaffrey as “Livleen” Noureen DeWulf as “Reena” Russell Peters as “Sonu” Rob Lowe as “Coach Winters” FEATURE SHEET Form: Feature Film Genre: Family, Cross Cultural, Comedic Drama Runtime: 95 min Date of Completion: June 30th, 2011 Expected to be Premiered at TIFF (Toronto International Film Festival) September 2011 Country of Production: Canada Country of Filming: Canada Production Budget: $12M CDN Producers / Fund Source: Hari Om Entertainment, First Take Entertainment Whizbang Films, Caramel Productions Don Carmody Productions, TeleFilm Canada CBC TV (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation) Distribution: Canada – Alliance Films India – Hari Om Entertainment All other international territories currently available LEAD CAST Vinay Virmani as Rajveer Singh Russell Peters as Sonu Camilla Belle as Melissa Winters Anupam Kher as Darvesh Singh Rob Lowe as Coach Dan Winters Sakina Jaffrey as Livleen Singh Gurpreet Ghuggi as Uncle Sammy Noureen DeWulf as Reena Cameo Appearances Akshay Kumar Aubrey “DRAKE” Graham Chris “LUDACRIS” Bridges SYNOPSIS BACKGROUND: BREAKAWAY, is a cross-cultural hockey drama set in the Indo-Canadian community in suburban Toronto, Canada. The movie is a full action, colourful, humourous, heart-felt musical. The setting is an obstacle-strewn love story with a dramatic quest for the hero. It’s also a keenly observed cross-cultural drama in the same classification as Bend It Like Beckham and Slumdog Millionaire with a hero caught between a family’s traditional expectations and a dream to make it big in the national sport of an adopted country. -

Motherhood and the Political Project of Queer Indian Cinema

Syracuse University SURFACE Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects Projects Spring 5-1-2007 Motherhood and the Political Project of Queer Indian Cinema Bryce J. Renninger Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/honors_capstone Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, Radio Commons, Religion Commons, and the Television Commons Recommended Citation Renninger, Bryce J., "Motherhood and the Political Project of Queer Indian Cinema" (2007). Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects. 560. https://surface.syr.edu/honors_capstone/560 This Honors Capstone Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Motherhood and the Political Project of Queer Indian Cinema Bryce J. Renninger Candidate for B.A. Degree in English & Textual Studies, Television Radio Film, and Religion & Society with Honors May 2007 APPROVED Thesis Project Advisor: ____________________________ Roger Hallas Honors Reader: __________________________________ Tula Goenka Honors Director: __________________________________ Samuel Gorovitz Date:___________________________________________ Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………...i Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………...…iii Introduction………………………………………………………………………1 -

Comedy and Politics

Comedy and Politics The Daily Show’s influence on public opinion: framing and criticism in the 2004 and 2008 general elections Juul Weijers S4231473 American Studies 15 June, 2018 Supervisor: Prof. dr. Frank Mehring Second reader: Dr. S.A. Shobeiri Weijers, s4231473/1 ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND CULTURE Teacher who will receive this document: Prof. dr. Frank Mehring Title of document: Comedy and Politics – The Daily Show’s influence on public opinion: framing and criticism in the 2004 and 2008 general elections Name of course: Bachelor Thesis American Studies Date of submission: 15 June, 2018 Word Count: 17242 The work submitted here is the sole responsibility of the undersigned, who has neither committed plagiarism nor colluded in its production. Signed Juul Peter Marien Weijers, 15 June 2018 Name of student: Juul Weijers Student number: s4231473 Weijers, s4231473/2 Acknowledgments I would like to thank James E. Caron, professor at the University of Hawaii, contributor to the Journal of Studies in American Humor and author of “The Quantum Paradox of Truthiness: Satire, Activism, and the Postmodern Condition” for sending me his article free of charge. Professor Caron has been most accommodating, and his work regarding the distinction between comedy and politics has been most helpful. Without his ideas this thesis would have been not as good. I would also like to extend my thanks to Prof. dr. Frank Mehring of the Radboud University for his guidance during this thesis, as without his notes and literature suggestions this thesis would never have taken shape at all. Setting high standards, he urged me to make the best thesis I could possibly make. -

ÂI Try to Write Things on a Very Personal Place So They Resonate Into A

M THE STORYTELLERS Mandvi with THE MAGAZINE 8 Top Chef host Padma Lakshmi. India Abroad November 14, 2014 ry acter that no one was writing because they did not have a point of view a ve In the hilarious and the poignant about those people in the way that I did. gs on So I started writing characters based on myself, my parents, my family thin stories in Aasif Mandvi’s memoir and people I grew up with and stuff like that. I started writing these char - write nate acters that actually represented South Asians in a real way, at least ry to reso No Land’s Man, Arthur J Pais attempting to. ÂI t they What happened from that was that a lot of South Asians came to see e so finds a reflection on identity, race, Sakina’s Restaurant . It was a revelation, I think, for a lot of South Asian plac Ê audiences because they had never seen that play that was done by a South onal text and dislocation. Photographs by Asian about a South Asian family, that was done on the mainstream pers l con American stage! ltura Those of us who were not artists, those of us who were not actors, felt er cu Paresh Gandhi empowered by what you had done. It showed us we could aspire to be what a larg we wanted to and did not have to kill our identity. into ver two decades ago, Aasif Mandvi, who was wait - Yes! We got bus loads of South Asians coming from New Jersey, ing tables in New York, broke the rules and whis - Connecticut and Long Island. -

IAAC FIRST ANNUAL LITERARY FESTIVAL • November 7-9, 2014

IAAC FIRST ANNUAL LITERARY FESTIVAL • November 7-9, 2014 The First IAAC Literary Festival will feature work by authors whose heritage lies in the Indian subcontinent, as well as those who have written about a subject connected to any aspect of that part of the world. We will feature veteran as well as emerging authors along with publishers and literary agents in order to create exciting discussions surrounding the various genres and themes represented. Kickoff Book Launch, Aasif Mandvi’s No Land’s Man Closing Night Dinner Reception, Monday, November 3rd, 7:00-10:00pm. AICON Gallery, 35 Great Jones, NYC Sunday November 9th, 7 - 10 pm Smithsonian Museum of the American Indian, 5 Bowling Green, NYC. Opening Reception, Friday November 7th, 6:30 - 9:30 pm. Smithsonian Museum of the American Indian, Bowling Green, NYC New York Times Theatre Journalist Patrick Healy will engage Pulitzer Prize winning Prof. Akeel Bilgrami , Director of the South Asian Institute, Columbia University will Playwright Ayad Akhtar in conversation (along w/excerpts of his plays). Post-conver - engage Booker of booker author Salman Rushdie in conversation about his writing. sation reception with wine, hors d'oeuvres and music by Somdutta Pal Post-conversation reception with wine, hors d'oeuvres and music by Zoya November 8th, 2014 at The Mahmood Mamdani, Gary Bass, Neil Sharbari Ahmed, Renu Balakrishnan, Nayana Writing the South Asian LGBT community This Padukone, Jaya Kamlani. Moderated by Mitra Currimbhoy, Victor Rangel-Ribeiro, Shuvendu category emphasizes a diversity of lesbian, gay, bi - South Asia Institute, Knox Kalita Sen. Moderated by Rajika Bhandari sexual and transgender writing in all genres, includ - Hall, 606 West 122nd Street, Hot off the press: Recent History in South Asia Fiction - including Short Stories All imaginative ing fiction and nonfiction and works of varying Columbia University, NYC. -

Outstanding Performance by a Female Actor in a Leading Role JUDI DENCH

11.30.17 • BACKSTAGE.COM FOR YOUR SAG CONSIDERATION Outstanding Performance by a Female Actor in a Leading Role JUDI DENCH “ A ROYAL TRIUMPH INDEED. JUDI DENCH GIVES A TOUCHING, MAJESTIC PERFORMANCE.” NEW YORK OBSERVER “ J UDI DENCH GIVES A CAREER-HIGH TURN.” THE TIMES For more on this film, go to www.FocusFeaturesGuilds2017.com © 2017 FOCUS FEATURES LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. VICTORIA & ABDUL - BACKSTAGE - Final (BONUS) SAG LEADING FILM & TV DRAMA November 21, 2017 12:53 PM PST COVER 1, 4C VAB_Bckstge_11-29_Cvr1_1F STREET: 11/29/17 DUE: 11/21/17 BLEED: 9.5" X 11.25" • TRIM: 9" X 10.75" • SAFETY: .25" FROM TRIM FOR YOUR SAG CONSIDERATION OUTSTANDING PERFORMANCE BY A M A L E A C T O R I N A L E A D I N G R O L E DANIEL DAY-LEWIS OUTSTANDING PERFORMANCE BY A F E M A L E A C T O R I N A L E A D I N G R O L E VICKY KRIEPS © 2017 PHANTOM THREAD, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PHANTOM THREAD - BACKSTAGE - Final (BONUS) SAG LEADING FILM & TV DRAMA November 21, 2017 12:30 PM PST COVER 2, 4C PT_Bckstge_11-29_Cvr2_1F STREET: 11/29/17 DUE: 11/21/17 BLEED: 9.5" X 11.25" • TRIM: 9" X 10.75" • SAFETY: .25" FROM TRIM 11.30.17 • BACKSTAGE.COM Why screenwriter Steven Rogers cast Allison Janney as his “I, Tonya” villain How to land a spot on a film crew Comedian Aasif Mandvi serves up the drama for Hulu’s “Shut Eye” REALITY CHECK AND: 10+ PAGES OF Lilli Cooper and Ethan Slater on CASTING NOTICES realizing their dream of taking “SpongeBob SquarePants” to Broadway CONTENTS vol.