Less Trave L E D T H E C O N Servation R O

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MAU EBURU: Intensive Bongo Monitoring Begins

THE NEWSLETTER OF THE RHINO ARK CHARITABLE TRUST ISSUE 52 | MAY 2018 MAU EBURU: INTENSIVE BONGO MONITORING BEGINS page 7 page 13 page 15 MAU EBURU: MT. KENYA FENCE RHINO ARK COMMUNITY PROGRESSES AS FOUR NYERI OFFICE LIVELIHOODS ANIMAL GRIDS ARE OFFICIALLY UPDATE BEING BUILT OPENED EXECUTIVE DIRECTor’s VIEW CHRISTIAN LAMBRECHTS MANAGING KENYA’S WATER TOWERS: A NEW DAWN Since its inception, Rhino Ark’s conservation work has focused on Cover picture by Eric Kihiu implementing practical and tangible solutions to the challenges affecting Kenyan mountain forests and their biodiversity. At the core of our conservation are our fencing projects, implemented in all the ecosystems where we are operating. Rhino Ark does not work INSIDE ARKIVE in isolation. All our conservation interventions are implemented through public/private partnership that involve the two main Executive Director’s View 03 government agencies in charge of the management of the montane 04 Mau Eburu Ecosystem forests: Kenya Forest Service and Kenya Wildlife Service. As such, over the past 30 years, Rhino Ark has gained a unique wealth of 09 South Western Mau Ecosystem experience and understanding, including from the perspective of KFS and KWS, of the continued challenges and emerging issues 12 Mt. Kenya Ecosystem impacting on the conservation of our mountain forest and the 15 Aberdare Ecosystem wildlife therein. 17 Rhino Ark News Based on these 30 years of experience, but also the in-house expertise at Rhino Ark, we were recently invited to be part of 18 Hog Charge the Government Task Force on the inquiry into Forest Resources 20 The Raffle Donors Management and Logging Activities in Kenya, where I chaired the Forest Conservation Committee. -

Fence Maintenance

THE NEWSLETTER OF THE RHINO ARK CHARITABLE TRUST ISSUE 56 | MAY 2020 FENCE MAINTENANCE: A TEAM EFFORT THAT REQUIRES CONTINUED SUPPORT page 9 page 12 page 23 SPECIAL EBURU FARMERS CONSERVATION FORMALIZING THE COVID-19 TAKE TO BIOGAS EDUCATION INITIATIVE PARTNERSHIP FOR TO CONSERVE THE BRINGS BIG GAINS TO FENCING KAKAMEGA ISSUE FOREST SOUTH WESTERN MAU FOREST SCHOOLS Remote Teaching and Learning #strongertogether Confident Individuals Responsible Citizens Learners Enjoying Success braeburn.com EXECUTIVE Director’S VIEW CHRISTIAN LAMBRECHTS We are in an era of unprecedented focus on the conservation of nature and forests, driven by the need to secure our collective sustainable future. Cover picture by Adam Mwangi Amid the disruptions occasioned by the COVID-19 pandemic, there INSIDE ARKIVE remains a constant, most challenging threat in the background: climate change. Every year new reports are published observing that the changes are worse than predicted and that we are reaching 03 Executive Director’s View dangerous tipping points beyond which changes are irreversible. 04 Special Feature But solutions exist. In a 2018 special Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report, the global scientific community 07 Mau Eburu Ecosystem highlighted the key role that forests will play in all pathways to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. 12 South Western Mau Ecosystem 16 Mt. Kenya Ecosystem Here in Kenya, each of us have experienced the impacts of climate change. Rainy seasons are becoming more variable and extreme 20 Aberdare Ecosystem rainfall events more frequent. Our mountain areas are experiencing reduced cloudiness, making our forests drier and more vulnerable 23 Kakamega Ecosystem to fires in the dry seasons. -

Saving Vultures from Poisoning Scourge Climbing Uganda’S Mountains of the Moon

COVID-19 EFFECTS ON WILDLIFE CONSERVATION SAVING VULTURES FROM POISONING SCOURGE CLIMBING UGANDA’S MOUNTAINS OF THE MOON ILLEGAL TRADE IN CHEETAH CUBS UNABATED PROFILES OF BIG 5 OF WILDLIFE FILMMAKERS MARK DEEBLE & PHOTOGRAPHY VICTORIA STONE INITIATIVE FRONTLINE 05 Director’s Letter 08 David Western critiques the Nairobi National Park draft management plan. 10 News Update OPINION 22 Benjamin Mkapa urges African governments to 39 The illegal trade in cheetah cubs caught in the wild provide greater support to conservation efforts and continues unabated, as Rupi Mangat reports. tourism. 43 Kakamega Forest, the only equatorial rainforest CONSERVATION in Kenya, has been earmarked for sustainable 24 Felix Patton throws some light on how the management, as Storm Stanley explains. coronavirus pandemic has affected wildlife conservation. 47 An elephant named Chemukung is recovering well from injuries sustained in a snaring ordeal in 31 Brothers Myles and Rory Root adventure into the Kenya’s Mt Elgon, as Stephen Powles and Charles wild in aid of an anti-poaching effort. Kerfoot report. 34 Kari Mutu highlights concerted efforts to save 51 Wildlife photographer Graeme Green explains his vultures from the scourge of poisoning. brainchild of Big 5 of Wildlife Photography. 4 | JULY - SEPTEMBER 2020 BIODIVERSITY 56 The Secretary bird, the world’s tallest raptor, is on the decline, as Kari Mutu reports. SCIENCE & RESEARCH 58 Ingo Lehmann throws describes on Kenya’s coastal 71 Benjamin Cowburn reports on an ongoing study Kaya forests and the mysteries of metarbelidae that suggests that some coral reefs in Watamu Marine carpenter moths found therein. National Park may be adapting to better cope with heat stress. -

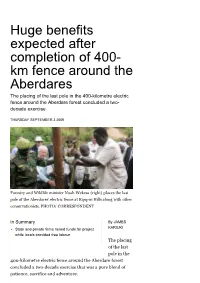

Huge Benefits Expected After Completion of 400 Km Fence Around

Huge benefits expected after completion of 400 km fence around the Aberdares The placing of the last pole in the 400kilometre electric fence around the Aberdare forest concluded a two decade exercise THURSDAY SEPTEMBER 3 2009 Forestry and Wildlife minister Noah Wekesa (right) places the last pole of the Aberdares’ electric fence at Kipipiri Hills along with other conservationists. PHOTO/ CORRESPONDENT In Summary By JAMES State and private firms raised funds for project KARIUKI while locals provided free labour The placing of the last pole in the 400kilometre electric fence around the Aberdare forest concluded a twodecade exercise that was a pure blend of patience, sacrifice and adventure. The stakeholders’ patience was stretched to the farthest limit by the numerous challenges and outright risks that the exercise came with. But none left Kenyans holding their collective breath like the television images that captured a helicopter carrying top executives on a tour to assess progress of the exercise crashing after it developed problems. The then Nation Media Group Chief Executive Officer, Mr Wilfred Kiboro, Rhino Ark chairman Collin Church, Safaricom’s Michael Joseph and Eddy Njoroge of KenGen all miraculously escaped by the skin of their teeth from the chopper crash on April 8, 2004. However, these setbacks never derailed the commitment by the government and private sector players who had helped raise the hundreds of millions of shillings needed to ring the conservancy. The contribution of simple village folks who put in unpaid manhours to erect the fence was vital for the success of the project. It was a joy last Friday to see representatives of the groups and local community turn up to witness what amounted to the final rite to the whole exercise. -

Safaricom Foundation Grants Rhino Ark Ksh 155 Million for Mau

THE NEWSLETTER OF THE RHINO ARK CHARITABLE TRUST NO. 40 MAY 2012 Safaricom Foundation Grants Rhino Ark RHINO Ksh 155 million For Mau Eburu CHAE RG ‘ 12 The Safaricom Foundation will provide Rhino Ark Ksh • Establishment of tree nurseries for communities 155 million for the restoration of the Mau Eburu Forest under the self-sustainable principle developed by It’s a way of life and its wider ecosystem. Rhino Ark; ……63 cars for The funds will be rolled out over a four-year period • Planning and development of compatible starting with immediate effect. livelihood projects that will earn income for forest- the 2012 Charge The grant was announced on April 3rd 2012 at a press edge communities; The 24th annual Rhino Charge conference in the Michael Joseph Centre at Safaricom • Creation of conditions for a broader ecosystem – Kenya’s self created unique House, Nairobi. conservation effort to enable wildlife corridors to motor sport off-road event – is just weeks away. Among the activities in which the funds will play a function through Eburu Forest linking the East Mau role are: and Lake Naivasha range and wetlands areas; and “The Rhino Charge is more • Protect the forest’s considerable biodiversity and than just an extreme sport, • Support for the Rhino Ark Eburu Forest Electric it becomes a way of life”, Fence to its completion; particularly its outstanding birdlife and threatened wildlife including a special effort to support the mouthed one veteran entrant • Restoration of areas degraded by unsolicited critically endangered Eastern Mountain Bongo. as he spat oil from his mouth encroachment; whilst fixing an undercar- A portion of the funds will also be set aside for an • Resolving of human/wildlife conflict with the riage oil seal on his bush endowment to be managed by a Trust in which the scarred Land Rover. -

Impact of Conservation

FACT SHEET 2 Impact of 30 years of Conservation The lessons learned from the successful fencing projects undertaken for Most of Kenya’s forests are in mountain areas – in Mount Kenya, Aberdares, Mount Eburu and Mount Kenya have opened up other forested areas the Aberdares, the Mau complex, the Cherangani Hills, and Mount for fence protection. These now include the South Western Mau and possibly Elgon. They are known as the ‘water towers’ of Kenya, forming the the Kakamega Forest in western Kenya. upper catchment of all main rivers of Kenya. The water towers are vital national assets in terms of climate regulation, water storage, Building a fence is one part of the equation. Equally, fences need to be recharge of groundwater, river flow regulation, flood migration, maintained and protected. In the Aberdares, parts of the fence are over control of soil erosion, and conservation of biological diversity. 20 years old and have to be replaced. Vigilance, too, is a crucial part of fence They are Kenya’s single most important source of water for direct management. Working with its partners, Rhino Ark conducts ground and aerial human consumption and for industrial and farming activities. The patrols and surveys of the forested areas it covers – identifying illegal activities majority of Kenyan livelihoods depend in some way on the rivers, and taking remedial action as necessary. Engaging local communities has been climate, forest and wildlife of these mountain ecosystems. They also an essential part of Rhino Ark strategy – both to guard and protect the fences. help mitigate the impacts of climate change, such as flooding. -

Arkive Nov 2018

THE NEWSLETTER OF THE RHINO ARK CHARITABLE TRUST ISSUE 53 | NOV 2018 RHINO ARK’S 30 YEARS... IN CONSERVING KENYA’S MOUNTAIN FORESTS page 19 page 22 page 24 MAU EBURU: WILDLIFE S.W. MAU: FOREST MT. KENYA: PATROL CORRIDOR MONITORING REHABILITATION WORK MONITORING SYSTEM SYSTEM IN PLACE COMMENCES FURTHER EXPANDED ON MT. KENYA With over 40 years operating, Braeburn is a well established group of International Schools, providing a world class education to over 4000 pupils. Our schools actively value and celebrate diversity, nurturing personal growth by providing a friendly and supportive environment. Confident Individuals Responsible Citizens Learners Enjoying Success P.O. Box 45112 00100 Nairobi Kenya • Tel: +254 (0)722 386 679 Email: [email protected] www.braeburn.com Photography by: Eric Kihiu EXECUTIVE DIRECTor’s viEW CHRISTIAN LAMBRECHTS INSIDE ARKIVE Rhino Ark and our annual Rhino Charge fundraiser have just turned 04 2018 Results and Awards 30. The achievements over the past three decades place our work at the summit of conservation efforts in Kenya. But the journey 05 Rhino Charge Millionaires since the humble beginnings in 1988 is even more remarkable. The journey is about individual belief and commitment. It is about Special Feature 08 not just discussing solutions and sharing ideas, but investing the 10 Car Sponsors necessary time and energy to actualize these ideas. It is also about leadership: engaging and empowering people to take care of public 16 Rhino Ark Audited Accounts goods, including the environment, hence securing their future and the future of the entire society. 18 Rhino Ark News At the outset, there was one man, Ken Kuhle, an engineer with a 19 Highlights from the Mountains strong passion for conservation. -

Fence Maintenance

THE NEWSLETTER OF THE RHINO ARK CHARITABLE TRUST ISSUE 56 | MAY 2020 FENCE MAINTENANCE: A TEAM EFFORT THAT REQUIRES CONTINUED SUPPORT page 9 page 12 page 23 SPECIAL EBURU FARMERS CONSERVATION FORMALIZING THE COVID-19 TAKE TO BIOGAS EDUCATION INITIATIVE PARTNERSHIP FOR TO CONSERVE THE BRINGS BIG GAINS TO FENCING KAKAMEGA ISSUE FOREST SOUTH WESTERN MAU FOREST SCHOOLS Remote Teaching and Learning #strongertogether Confident Individuals Responsible Citizens Learners Enjoying Success braeburn.com EXECUTIVE Director’S VIEW CHRISTIAN LAMBRECHTS We are in an era of unprecedented focus on the conservation of nature and forests, driven by the need to secure our collective sustainable future. Cover picture by Adam Mwangi Amid the disruptions occasioned by the COVID-19 pandemic, there INSIDE ARKIVE remains a constant, most challenging threat in the background: climate change. Every year new reports are published observing that the changes are worse than predicted and that we are reaching 03 Executive Director’s View dangerous tipping points beyond which changes are irreversible. 04 Special Feature But solutions exist. In a 2018 special Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report, the global scientific community 07 Mau Eburu Ecosystem highlighted the key role that forests will play in all pathways to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. 12 South Western Mau Ecosystem 16 Mt. Kenya Ecosystem Here in Kenya, each of us have experienced the impacts of climate change. Rainy seasons are becoming more variable and extreme 20 Aberdare Ecosystem rainfall events more frequent. Our mountain areas are experiencing reduced cloudiness, making our forests drier and more vulnerable 23 Kakamega Ecosystem to fires in the dry seasons. -

KFS Board Inaugurated

A Quartely Magazine of the Kenya Forest Service Issue No. 15 : January - June 2015 KFS Board Inaugurated Kenya and Tanzania Sign Pact to Curtail Illegal Movement of Forest Produce Western Regime Tree Planting Kicks Off Forest Rangers Recruited THE FORESTER :: JANUARY -JUNE 2015 1 FROM THE EDITOR In this issue of the Forester Magazine, we cover news and feature stories touching on activities that took place in the last three months and a forecast of activities that will take place within the year. The Service continues in its quest to ensure the security and continuity of our country’s forests as one of its mandates, for- est areas which continue to be subject to various forms of destruc- tion. In conjunction with the Ministry of Environment, Water and Natural Resources and the World Bank, the Service also con- tinues to facilitate dialogue and foster cooperation with forest ad- jacent communities for the continued sustainable management of forests. Towards this, a number of Forest Management Agreements have been successfully signed and launched across the country with the latest Plan being launched in Jilore Forest Block, Kilifi County. The Service also continues to implement the Green Schools pro- gramme together with the Ministry of Environment in an initiative geared towards increasing the country’s tree cover as well as as- sisting public schools generate extra income through commercial forestry. Earlier this year, the Service began an exercise involving all County Governments geared towards transferring devolved forestry functions to Counties. Towards this, a number of regional workshops took place in various parts of the country to help kick off the Transitional Implementation Plans (TIPs) as required by the Constitution. -

ACCESSING FUNDING for Conservanon and RESEARCH WORK in KENYA

Accessing Funding for Conservation and Research Work in Kenya: presented at a workshop on 'Writing Funding Proposals and Communcating Results', National Museums of Kenya 10-12 May 2004. Item Type Report Authors Ruhiu, J.M. Publisher CDTF, Biodiversity Conservation Programme (BCP) Download date 01/10/2021 14:16:14 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/6993 ACCESSING FUNDING FOR CONSERVAnON AND RESEARCH WORK IN KENYA By Joseph M. Ruhiu Technical OffIcer-Wildlife & Environment Biodiversity Conservation Programme (BCP) - E-mail [email protected] Presented at a workshop on Writing Funding Proposals and Communicating Results National Museums of Kenya lO_12th May 2004 Summary Developing countries have limitedfinancial resources to support conservation and research and even where finances are incorporated in government budgets, these are inadequate. Kenya has a diverse assemblage of natural resources requiring huge financial resources. Although wildlife tourism generates up to US$ 27 million annually and a third of foreign exchange earnings, contributing up to 10% to formal employment and 5% to GDP, little of this fund is ploughed back either to support conservation or to benefit communities which support conservation. Most of the generated income is repatriated to developed nations and up to 55% of generated resources is believed to remain in developed nations where booking and marketing are carried out. Conservation has both public and private costs. Management costs are estimated at US$ 25 million and opportunity cost of conserving wildlife habitats in terms of alternative land uses forgone estimated at US$200 million per year. Wildlife related damage is estimated at 35-45 of total production in wildlife areas. -

Arkive April

THE NEWSLETTER OF THE RHINO ARK CHARITABLE TRUST NO. 34 MAY 2009 Rhino Charge 2009 Roars off May 31 The world famous, world unique Rhino Charge 4x4 off-road event, is fully subscribed. Vehicles - of all shapes and types – some with mind boggling modifications and ordinary 4x4s will compete. This year’s event is slated for the 31st May at a secret location which will be unveiled the day before the event by the Clerk of Course Anton Levitan. Money raised from this event is used for the building and maintenance of Rhino Ark’s fence, helping to conserve one of Kenya’s finest indigenous forests and its total habitat. “Entries are strongly competed for under Community in conservation: Members of the Kipipiri community assist in fence construction. Rhino Ark’s pledge system whereby Continued on page 5 Aberdare Fence... final Chargers Rev up! countdown to completion The event that raises the greatest funds for conservation in Kenya’s history – the annual Rhino Charge is just weeks away! The Aberdare Fence will be completed by the 82 km Phase Five in 2003-05. Our September this year. It will be a distance teams are carrying every post, rolls of of almost 400 kms. (see map on page 4) heavy wire, nails and insulators as much as 1.5 kms to reach sections of the fence As of March 31 this year, 21 kms of the line. Roads do not reach such areas. The Kipipiri Extra Section totalling approxi- Eastern side near Gaita will be easier and mately 40 kms in length was com- faster to build. -

Annual Report and Financial Statements 2011

Annual Report and Financial Statements 2011 i Contents Board of Trustees iii Our Core Statements iv List of Abbreviations and Acronyms v Chairman’s Statement vi Director’s Statement viii Wildlife Conservation 1 Law Enforcement 8 Service Delivery 12 Wangari Maathai 18 Financial Statements 24 KWS Park Visitor Numbers 43 List of Partners 44 KWS Contact Addresses 46 ii Board of Trustees Hon David Mwiraria Margaret Wawuda Julius Kipng`etich Chairman Vice Chair Director Winnie Kiiru Dr Thomas Manga Edward Ngigi Member Member Member Gideon Gathaara David Mbugua Ian Craig Rep. Permanent Secretary Member Member Ministry of Forestry and Wildlife iii Board of Trustees Felix Oulo Hassan Noor Hassan Patricia Awori Member Member Member Nicholas Ole Kamwaro Adil Khawaja Stephen Karani Member Member Rep. PS Ministry of Finance Julius Ndegwa Mutea Iringo Rep. Commissioner of Police Rep. PS Office of the President and Internal Security iv Our Core Statements To be a world leader in wildlife conservation To sustainably conserve and manage Kenya’s wildlife and its habitats in collaboration with stakeholders for posterity Our Vision At KWS, we conserve and manage Kenya’s wildlife scientifically, responsively and professionally. We do this Ourwith integrity, Mission recognising and encouraging staff creativity and continuous learning and teamwork inpartnership with communities and stakeholders. Value Statement v List of Abbreviations and Acronyms AP Administration Police BATUK British Army Training Unit in Kenya CITES Convention on International Trade in Endangered