AICPA Comments on IRS Virtual Currency Guidance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rev. Rul. 2019-24 ISSUES (1) Does a Taxpayer Have Gross Income Under

26 CFR 1.61-1: Gross income. (Also §§ 61, 451, 1011.) Rev. Rul. 2019-24 ISSUES (1) Does a taxpayer have gross income under § 61 of the Internal Revenue Code (Code) as a result of a hard fork of a cryptocurrency the taxpayer owns if the taxpayer does not receive units of a new cryptocurrency? (2) Does a taxpayer have gross income under § 61 as a result of an airdrop of a new cryptocurrency following a hard fork if the taxpayer receives units of new cryptocurrency? BACKGROUND Virtual currency is a digital representation of value that functions as a medium of exchange, a unit of account, and a store of value other than a representation of the United States dollar or a foreign currency. Foreign currency is the coin and paper money of a country other than the United States that is designated as legal tender, circulates, and is customarily used and accepted as a medium of exchange in the country of issuance. See 31 C.F.R. § 1010.100(m). - 2 - Cryptocurrency is a type of virtual currency that utilizes cryptography to secure transactions that are digitally recorded on a distributed ledger, such as a blockchain. Units of cryptocurrency are generally referred to as coins or tokens. Distributed ledger technology uses independent digital systems to record, share, and synchronize transactions, the details of which are recorded in multiple places at the same time with no central data store or administration functionality. A hard fork is unique to distributed ledger technology and occurs when a cryptocurrency on a distributed ledger undergoes a protocol change resulting in a permanent diversion from the legacy or existing distributed ledger. -

White Paper of Bitcoin Ultimatum Introduction

White Paper of Bitcoin Ultimatum Introduction 1. Problematic of the Blockchain 4. Bitcoin Ultimatum Architecture industry 4.1. Network working principle 1.1. Transactions Anonymity 4.1.1. Main Transaction Types 1.2. Insufficient Development of Key Aspects of the 4.1.1.1. Public transactions Technology 4.1.1.2. Private transactions 1.3. Centralization 4.1.2. Masternode Network 1.4. Mining pools and commission manipulation 4.2. How to become a validator or masternode in 1.5. Decrease in Transaction Speeds BTCU 4.3. Network Scaling Principle 2. BTCU main solutions and concepts 4.4. Masternodes and Validators Ranking System 4.5. Smart Contracts 2.1. Consensus algorithm basis 4.6. Anonymization principle 2.2. Leasing and Staking 4.7. Staking and Leasing 2.3. Projects tokenization and DeFi 4.7.1. Staking 2.4. Transactions Privacy 4.7.2. Leasing 2.5. Atomic Swaps 4.7.2 Multileasing 4.8. BTCU Technical Specifications 3. Executive Summary 4.8.1. Project Stack 4.8.2. Private key generation algorithm 5. Bitcoin Ultimatum Economy 5.1. Initial Supply and Airdrop 5.2. Leasing Economy 5.3. Masternodes and Validators Commission 5.4. Transactions Fee 6. Project Roadmap 7. Legal Introduction The cryptocurrency market is inextricably tied to the blockchain – its fundamental and underlying technology. The modern market is brimming with an abundance of blockchain protocols, algorithms, and concepts, all of which have fostered the development of a wide variety of services and applications. The modern blockchain market offers users an alternative to both established financial systems and ecosystems/infrastructures of applications and services. -

Virtual Currency Schemes of 2012

VIRTUAL CURRENCY SCHEMES OCTOBER 2012 VIRTUAL CURRENCY SCHEMES OctoBer 2012 In 2012 all ECB publications feature a motif taken from the €50 banknote. © European Central Bank, 2012 Address Kaiserstrasse 29 60311 Frankfurt am Main Germany Postal address Postfach 16 03 19 60066 Frankfurt am Main Germany Telephone +49 69 1344 0 Website http://www.ecb.europa.eu Fax +49 69 1344 6000 All rights reserved. Reproduction for educational and non-commercial purposes is permitted provided that the source is acknowledged. ISBN: 978-92-899-0862-7 (online) CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 1 INTRODUCTION 9 1.1 Preliminary remarks and motivation 9 1.2 A short historical review of money 9 1.3 Money in the virtual world 10 2 VIRTUAL CURRENCY SCHEMES 13 2.1 Definition and categorisation 13 2.2 Virtual currency schemes and electronic money 16 2.3 Payment arrangements in virtual currency schemes 17 2.4 Reasons for implementing virtual currency schemes 18 3 CASE STUDIES 21 3.1 The Bitcoin scheme 21 3.1.1 Basic features 21 3.1.2 Technical description of a Bitcoin transaction 23 3.1.3 Monetary aspects 24 3.1.4 Security incidents and negative press 25 3.2 The Second Life scheme 28 3.2.1 Basic features 28 3.2.2 Second Life economy 28 3.2.3 Monetary aspects 29 3.2.4 Issues with Second Life 30 4 THE RELEVANCE OF VIRTUAL CURRENCY SCHEMES FOR CENTRAL BANKS 33 4.1 Risks to price stability 33 4.2 Risks to financial stability 37 4.3 Risks to payment system stability 40 4.4 Lack of regulation 42 4.5 Reputational risk 45 5 CONCLUSION 47 ANNEX: REFERENCES AND FURTHER INFORMATION ON VIRTUAL CURRENCY SCHEMES 49 ECB Virtual currency schemes October 2012 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Virtual communities have proliferated in recent years – a phenomenon triggered by technological developments and by the increased use of the internet. -

Cryptocurrency: the Economics of Money and Selected Policy Issues

Cryptocurrency: The Economics of Money and Selected Policy Issues Updated April 9, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45427 SUMMARY R45427 Cryptocurrency: The Economics of Money and April 9, 2020 Selected Policy Issues David W. Perkins Cryptocurrencies are digital money in electronic payment systems that generally do not require Specialist in government backing or the involvement of an intermediary, such as a bank. Instead, users of the Macroeconomic Policy system validate payments using certain protocols. Since the 2008 invention of the first cryptocurrency, Bitcoin, cryptocurrencies have proliferated. In recent years, they experienced a rapid increase and subsequent decrease in value. One estimate found that, as of March 2020, there were more than 5,100 different cryptocurrencies worth about $231 billion. Given this rapid growth and volatility, cryptocurrencies have drawn the attention of the public and policymakers. A particularly notable feature of cryptocurrencies is their potential to act as an alternative form of money. Historically, money has either had intrinsic value or derived value from government decree. Using money electronically generally has involved using the private ledgers and systems of at least one trusted intermediary. Cryptocurrencies, by contrast, generally employ user agreement, a network of users, and cryptographic protocols to achieve valid transfers of value. Cryptocurrency users typically use a pseudonymous address to identify each other and a passcode or private key to make changes to a public ledger in order to transfer value between accounts. Other computers in the network validate these transfers. Through this use of blockchain technology, cryptocurrency systems protect their public ledgers of accounts against manipulation, so that users can only send cryptocurrency to which they have access, thus allowing users to make valid transfers without a centralized, trusted intermediary. -

Cryptocurrencies As an Alternative to Fiat Monetary Systems David A

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Digital Commons at Buffalo State State University of New York College at Buffalo - Buffalo State College Digital Commons at Buffalo State Applied Economics Theses Economics and Finance 5-2018 Cryptocurrencies as an Alternative to Fiat Monetary Systems David A. Georgeson State University of New York College at Buffalo - Buffalo State College, [email protected] Advisor Tae-Hee Jo, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Economics & Finance First Reader Tae-Hee Jo, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Economics & Finance Second Reader Victor Kasper Jr., Ph.D., Associate Professor of Economics & Finance Third Reader Ted P. Schmidt, Ph.D., Professor of Economics & Finance Department Chair Frederick G. Floss, Ph.D., Chair and Professor of Economics & Finance To learn more about the Economics and Finance Department and its educational programs, research, and resources, go to http://economics.buffalostate.edu. Recommended Citation Georgeson, David A., "Cryptocurrencies as an Alternative to Fiat Monetary Systems" (2018). Applied Economics Theses. 35. http://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/economics_theses/35 Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/economics_theses Part of the Economic Theory Commons, Finance Commons, and the Other Economics Commons Cryptocurrencies as an Alternative to Fiat Monetary Systems By David A. Georgeson An Abstract of a Thesis In Applied Economics Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts May 2018 State University of New York Buffalo State Department of Economics and Finance ABSTRACT OF THESIS Cryptocurrencies as an Alternative to Fiat Monetary Systems The recent popularity of cryptocurrencies is largely associated with a particular application referred to as Bitcoin. -

The Nature of Decentralized Virtual Currencies: Benefits, Risks and Regulations

MILE 14 Thesis | Fall 2014 The Nature of Decentralized Virtual Currencies: Benefits, Risks and Regulations. Paul du Plessis Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Kern Alexander 1 DECLARATION This master thesis has been written in partial fulfilment of the Master of International Law and Economics Programme at the World Trade Institute. The ideas and opinions expressed in this paper are made independently, represent my own views and are based on my own research. I confirm that this work is my own and has not been submitted for academic credit in any other subject or course. I have acknowledged all material and sources used in this paper. I understand that my thesis may be made available in the World Trade Institute library. 2 ABSTRACT Virtual currency schemes have proliferated in recent years and have become a focal point of media and regulators. The objective of this paper is to provide a description of the technical nature of Bitcoin and the reason for its existence. With an understanding of the basic workings of this new payment system, we can draw comparisons to fiat currency, analyze the associated risks and benefits, and effectively discusses the current regulatory framework. 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1. Introduction .............................................................................................. 4 2. The Evolution of Money .......................................................................... 6 2.1. Defining Money ................................................................................. 6 2.2. The Origin of Money ........................................................................ -

Blockchain & Cryptocurrency Regulation

Blockchain & Cryptocurrency Regulation Third Edition Contributing Editor: Josias N. Dewey Global Legal Insights Blockchain & Cryptocurrency Regulation 2021, Third Edition Contributing Editor: Josias N. Dewey Published by Global Legal Group GLOBAL LEGAL INSIGHTS – BLOCKCHAIN & CRYPTOCURRENCY REGULATION 2021, THIRD EDITION Contributing Editor Josias N. Dewey, Holland & Knight LLP Head of Production Suzie Levy Senior Editor Sam Friend Sub Editor Megan Hylton Consulting Group Publisher Rory Smith Chief Media Officer Fraser Allan We are extremely grateful for all contributions to this edition. Special thanks are reserved for Josias N. Dewey of Holland & Knight LLP for all of his assistance. Published by Global Legal Group Ltd. 59 Tanner Street, London SE1 3PL, United Kingdom Tel: +44 207 367 0720 / URL: www.glgroup.co.uk Copyright © 2020 Global Legal Group Ltd. All rights reserved No photocopying ISBN 978-1-83918-077-4 ISSN 2631-2999 This publication is for general information purposes only. It does not purport to provide comprehensive full legal or other advice. Global Legal Group Ltd. and the contributors accept no responsibility for losses that may arise from reliance upon information contained in this publication. This publication is intended to give an indication of legal issues upon which you may need advice. Full legal advice should be taken from a qualified professional when dealing with specific situations. The information contained herein is accurate as of the date of publication. Printed and bound by TJ International, Trecerus Industrial Estate, Padstow, Cornwall, PL28 8RW October 2020 PREFACE nother year has passed and virtual currency and other blockchain-based digital assets continue to attract the attention of policymakers across the globe. -

Central Bank Cryptocurrencies1

Morten Bech Rodney Garratt [email protected] [email protected] Central bank cryptocurrencies1 New cryptocurrencies are emerging almost daily, and many interested parties are wondering whether central banks should issue their own versions. But what might central bank cryptocurrencies (CBCCs) look like and would they be useful? This feature provides a taxonomy of money that identifies two types of CBCC – retail and wholesale – and differentiates them from other forms of central bank money such as cash and reserves. It discusses the different characteristics of CBCCs and compares them with existing payment options. JEL classification: E41, E42, E51, E58. In less than a decade, bitcoin has gone from being an obscure curiosity to a household name. Its value has risen – with ups and downs – from a few cents per coin to over $4,000. In the meantime, hundreds of other cryptocurrencies – equalling bitcoin in market value – have emerged (Graph 1, left-hand panel). While it seems unlikely that bitcoin or its sisters will displace sovereign currencies, they have demonstrated the viability of the underlying blockchain or distributed ledger technology (DLT). Venture capitalists and financial institutions are investing heavily in DLT projects that seek to provide new financial services as well as deliver old ones more efficiently. Bloggers, central bankers and academics are predicting transformative or disruptive implications for payments, banks and the financial system at large.2 Lately, central banks have entered the fray, with several announcing that they are exploring or experimenting with DLT, and the prospect of central bank crypto- or digital currencies is attracting considerable attention. But making sense of all this is difficult. -

On the Security of Electroneum Cloud Mining

This Selfie Does Not Exist: On the Security of Electroneum Cloud Mining Alexander Marsalek1, Edona Fasllija2 and Dominik Ziegler3 1Secure Information Technology Center Austria, Vienna, Austria 2Institute for Applied Information Processing and Communications (IAIK), Graz University of Technology, Graz, Austria 3Know-Center GmbH, Graz, Austria Keywords: Electroneum Cloud Mining, Cryptocurrency, Impersonation Attack, Image Manipulation. Abstract: The Electroneum cryptocurrency provides a novel mining experience called “cloud mining”, which enables iOS and Android users to regularly earn cryptocurrency tokens by simply interacting with the Electroneum app. Besides other security countermeasures against automated attacks, Electroneum requires the user to up- load selfies with a predefined gesture or a drawing of a symbol as a prerequisite for the activation of the mining process. In this paper, we show how a malicious user can circumvent all of these security features and thus create and maintain an arbitrary number of fake accounts. Our impersonation attack particularly focuses on creating non-existing selfies by relying on Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) techniques during account initialization. Furthermore, we employ reverse engineering to develop a bot that simulates the genuine Elec- troneum app and is capable of operating an arbitrary number of illegitimate accounts on one Android device, enabling the malicious user to obtain an unfairly large payout. 1 INTRODUCTION Rivet, 2019). Due to these effects, both Google and Apple prohibit cryptocurrency mining apps from their During 2017, the first and most popular cryptocurrency, application stores (Apple, 2019; Google, 2018), limiting Bitcoin, experienced an astonishing 13-fold increase in the accessibility of the average smartphone users to crypto mining. Despite this fact, several projects like value (Corcoran, 2017). -

NFT Yearly Report 2020, Fresh from the Oven!

NON-FUNGIBLE TOKENS YEARLY REPORT 2020 FREE EDITION MARKET RESEARCH. TRENDS DECRYPTION. PROJECT REVIEW. EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT THE NFT ECOSYSTEM FOREWORDS The NFT Yearly Report 2020, fresh from the oven! The purpose of this report is to provide an overarching and detailed view of the Non-Fungible Token ecosystem during 2020. The exponential growth within the sector has been particularly impressive, especially given that the Crypto bear market was in full force during most of the early stages of development. There is little doubt that the loyal and tight knit groups who initially evolved around various NFT blockchain projects have since seen the contents of their wallets dramatically increase in value as the ecosystem evolved and NFT projects began to attract more and more outside and mainstream interest. This report is not meant for Non-Fungible experts but to help everyone in or outside the Non- Fungible Tokens ecosystem to better understand what is going on. What is the potential? Why should you care about NFT? 2020 has been an unprecedented year for most of the world's population, with many challenges to face, from a global pandemic and lockdown to political upheavals, riots and not to mention catastrophic natural disasters… we’ve had it all! In stark contrast and perhaps partially due to such turbulent global events, interest and investment in virtual economies and digital assets has boomed, more than ever seen before. Within the Non-Fungible Token ecosystem individual sectors have seen success, Art, Gaming and Digital Assets have all gained remarkable traction during 2020 with this once niche and experimental industry maturing into a force to be reckoned with. -

What's in Your E-Wallet?

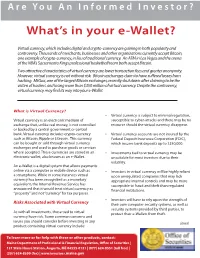

Are You An Informed Investor? What’s in your e-Wallet? Virtual currency, which includes digital and crypto-currency are gaining in both popularity and controversy. Thousands of merchants, businesses and other organizations currently accept Bitcoin, one example of crypto-currency, in lieu of traditional currency. An ATM in Las Vegas and the arena of the NBA’s Sacramento Kings professional basketball team both accept Bitcoin. Two attractive characteristics of virtual currency are lower transaction fees and greater anonymity. However, virtual currency is not without risk. Bitcoin exchanges claim to have suffered losses from hacking. MtGox, one of the largest Bitcoin exchanges, recently shut down after claiming to be the victim of hackers and losing more than $350 million of virtual currency. Despite the controversy, virtual currency may find its way into your e-Wallet. What is Virtual Currency? • Virtual currency is subject to minimal regulation, Virtual currency is an electronic medium of susceptible to cyber-attacks and there may be no exchange that, unlike real money, is not controlled recourse should the virtual currency disappear. or backed by a central government or central bank. Virtual currency includes crypto-currency • Virtual currency accounts are not insured by the such as Bitcoin, Ripple or Litecoin. This currency Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), can be bought or sold through virtual currency which insures bank deposits up to $250,000. exchanges and used to purchase goods or services where accepted. These currencies are stored in an • Investments tied to virtual currency may be electronic wallet, also known as an e-Wallet. unsuitable for most investors due to their volatility. -

Pay Toll with Coins: Looking Back on Fbar Penalties and Prosecutions to Inform the Future of Cryptocurrency Taxation

PAY TOLL WITH COINS: LOOKING BACK ON FBAR PENALTIES AND PROSECUTIONS TO INFORM THE FUTURE OF CRYPTOCURRENCY TAXATION Caroline T. Parnass* Cryptocurrencies are gaining a foothold in the global economy, and the government wants its cut. However, few people are reporting cryptocurrency transactions on their tax returns. How will the IRS solve its cryptocurrency noncompliance problem? Its response so far bears many similarities to the government’s campaign to increase Reports of Foreign Bank and Financial Accounts (FBARs). FBAR noncompliance penalties are notoriously harsh, and the government has pursued them vigorously. This Note explores the connections and differences between cryptocurrency reporting and foreign bank account reporting in an effort to predict the future regime of cryptocurrency tax compliance. * J.D. Candidate, 2021, University of Georgia School of Law; M.S., 2018, Georgia State University; B.A., 2013, Wellesley College. Thanks to Professor Camilla E. Watson for her help developing this Note. Dedicated to Nadia Tscherny, Ph.D. 359 360 GEORGIA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 55:359 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................... 361 II. WHAT IS CRYPTOCURRENCY? ............................................. 365 III. THE IRS’S RESPONSE TO CRYPTOCURRENCY ................... 369 A. ADMINISTRATIVE ACTS ............................................. 369 B. LEGAL ACTION .......................................................... 372 IV. FOREIGN BANK ACCOUNT REPORTING ............................