Philippines Campaign (1944–1945) - Wikipedia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Distribution and Nesting Density of the Philippine Eagle Pithecophaga

Ibis (2003), 145, 130–135 BlackwellDistribution Science, Ltd and nesting density of the Philippine Eagle Pithecophaga jefferyi on Mindanao Island, Philippines: what do we know after 100 years? GLEN LOVELL L. BUESER,1 KHARINA G. BUESER,1 DONALD S. AFAN,1 DENNIS I. SALVADOR,1 JAMES W. GRIER,1,2* ROBERT S. KENNEDY3 & HECTOR C. MIRANDA, JR1,4 1Philippine Eagle Foundation, VAL Learning Village, Ruby Street, Marfori Heights Subd., Davao City 8000 Philippines 2Department of Biological Sciences, North Dakota State University, Fargo, North Dakota 58105, USA 3Maria Mitchell Association, 4 Vestal Street, Nantucket, MA 02554, USA 4University of the Philippines Mindanao, Bago Oshiro, Davao City 8000 Philippines The Philippine Eagle Pithecophaga jefferyi, first discovered in 1896, is one of the world’s most endangered eagles. It has been reported primarily from only four main islands of the Philippine archipelago. We have studied it extensively for the past three decades. Using data from 1991 to 1998 as best representing the current status of the species on the island of Mindanao, we estimated the mean nearest-neighbour distances between breeding pairs, with remarkably little variation, to be 12.74 km (n = 13 nests plus six pairs without located nests, se = ±0.86 km, range = 8.3–17.5 km). Forest cover within circular plots based on nearest-neighbour pairs, in conjunction with estimates of remaining suitable forest habitat (approximately 14 000 km2), yield estimates of the maximum number of breeding pairs on Mindanao ranging from 82 to 233, depending on how the forest cover is factored into the estimates. The Philippine Eagle Pithecophaga jefferyi is a large insufficient or unreliable data, and inadequately forest raptor considered to be one of the three reported methods. -

World War Ii in the Philippines

WORLD WAR II IN THE PHILIPPINES The Legacy of Two Nations©2016 Copyright 2016 by C. Gaerlan, Bataan Legacy Historical Society. All Rights Reserved. World War II in the Philippines The Legacy of Two Nations©2016 By Bataan Legacy Historical Society Several hours after the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the Philippines, a colony of the United States from 1898 to 1946, was attacked by the Empire of Japan. During the next four years, thou- sands of Filipino and American soldiers died. The entire Philippine nation was ravaged and its capital Ma- nila, once called the Pearl of the Orient, became the second most devastated city during World War II after Warsaw, Poland. Approximately one million civilians perished. Despite so much sacrifice and devastation, on February 20, 1946, just five months after the war ended, the First Supplemental Surplus Appropriation Rescission Act was passed by U.S. Congress which deemed the service of the Filipino soldiers as inactive, making them ineligible for benefits under the G.I. Bill of Rights. To this day, these rights have not been fully -restored and a majority have died without seeing justice. But on July 14, 2016, this mostly forgotten part of U.S. history was brought back to life when the California State Board of Education approved the inclusion of World War II in the Philippines in the revised history curriculum framework for the state. This seminal part of WWII history is now included in the Grade 11 U.S. history (Chapter 16) curriculum framework. The approval is the culmination of many years of hard work from the Filipino community with the support of different organizations across the country. -

LAYOUT for 2UPS.Pmd

July-SeptemberJuly-September 20072007 PHILJA NEWS DICIA JU L EME CO E A R U IN C P R P A U T P D S I E L M I H Y P R S E S U S E P P E U N R N I I E B P P M P I L P E B AN L I ATAS AT BAY I C I C L H I O P O H U R E F T HE P T O F T H July to September 2007 Volume IX, Issue No. 35 EE xx cc ee ll ll ee nn cc ee ii nn tt hh ee JJ uu dd ii cc ii aa rr yy 2 PHILJA NEWS PHILJAPHILJA BulletinBulletin REGULAR ACADEMIC A. NEW APPOINTMENTS PROGRAMS REGIONAL TRIAL COURTS CONTINUING LEGAL EDUCATION PROGRAM REGION I FOR COURT ATTORNEYS Hon. Jennifer A. Pilar RTC Br. 32, Agoo, La Union The Continuing Legal Education Program for Court Attorneys is a two-day program which highlights REGION IV on the topics of Agrarian Reform, Updates on Labor Hon. Ramiro R. Geronimo Law, Consitutional Law and Family Law, and RTC Br. 81, Romblon, Romblon Review of Decisions and Resolutions of the Civil Hon. Honorio E. Guanlao, Jr. Service Commission, other Quasi-judicial Agencies RTC Br. 29, San Pablo City, Laguna and the Ombudsman. The program for the Hon. Albert A. Kalalo Cagayan De Oro Court of Appeals Attorneys was RTC Br. 4, Batangas City held on July 10 to 11, 2007, at Dynasty Court Hotel, Hon. -

Southeast Asia Treaty Organization

TWO PAPERS ON PHILIPPINE FOREIGN POLICY� The Philippines and the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization The Record of the Philippines in the United Nationsi . TWO PAPERS ON PHILIPPINE FORKIGN POLICY The Philippines and the Southeast 1lsia Treaty Organ-iz·at ion by . Roger. M. Smit•h; The Record of the Philippines in the United Nations by i�-ru F. Somerts Data Paper.: • Number 38 Southeast .Asia Progr�:m • � • I .... D�pa�ment of Far••• .Eastetn-· St-µdies.� -1;..., •. Cornell Uniye�sity,, Ithaca.,. N.ew..York December, 1959 Price $2.00 THE CORNELL trnlVImSITY SOUT�ST ASIA PROORAM The southeast Asia Program was organized at Cornell University in the- Department of Far Eastern studies in 19SO. :rt is a teaching and research pro gram of interdisciplinary studies in the humanities, social sciences and some natural sciences. It deals with southeast Asia �s a region, and with the in dividual countries of the area1 · Burma, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaya, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam. The activities of the Program are carried on both at Cornell and in Southeast Asia. They include an undergraduate and graduate . curriculum at Cornell which provides instruction by' specialists in South east Asian cultural history and present-day affairs and offers intensive training in each of the major languages of the area. The Program sponsors group research projects on Thailand, on Indonesia, on the Philippines, and on the area•s Chinese minorities. At the same time, individual staff' and students of the Program have done field research in every South east Asian country. A list of publicatoions relating to Southeast Asia which may be obtained on prepaid order directly from the Program is given at·othe end of this volume. -

10. Survey of Timber Entrepreneurs in Region 8 and Cebu, the Philippines: Preliminary Findings

10. SURVEY OF TIMBER ENTREPRENEURS IN REGION 8 AND CEBU, THE PHILIPPINES: PRELIMINARY FINDINGS Janet Cedamon, Edwin Cedamon, Steve Harrison, Nestor Gregorio, Eduardo Mangaoang and John Herbohn The lack of information by smallholders about market opportunities and the timber product requirements of buyers may be a major impediment to development of formal or regular timber markets. Anecdotal evidence suggests that growers fare poorly in terms of prices obtained under current arrangements, with consequent inadequate market signals to encourage tree planting. This paper presents preliminary results of a survey conducted to investigate the status and prospects of timber enterprises in Leyte and Cebu in the Philippines. The operators were interviewed in 51 timber enterprises, of which 34 are registered with the Department of Environment and Natural Resources. The majority (74%) of the enterprises were engaged in retailing sawn timber. About 58% obtained some or 61% obtained timber from timber merchants while 33% directly from tree growers. Respondents identified proper plantation management as one of the measures to improve the quality of timber from smallholder tree farmers. The present forest policies, support from the government, low quality of timber and insufficient supply of timber were nominated as problems experienced by the respondents. INTRODUCTION A substantial number of smallholders on Leyte Island in the Philippines have small-scale tree plantings on the land they own or cultivate (Cedamon and Emtage 2005). Emtage (2004) explained that there are clear opportunities for communities and smallholder tree farmers to supply timber products into local markets, if they can meet bureaucratic requirements for timber harvesting and transport. -

Establishing the Power Plant Contracts for the Leyte Geothermal Power Project

Javellanaet al. ESTABLISHING THE POWER PLANT CONTRACTS FOR THE LEYTE GEOTHERMAL POWER PROJECT P Javellana', B F M Dolor', M A Medado', M V de Jesus'. P R National Oil Company Energy Development Corporation, Manila, Philippines Morrison Ltd, Auckland. New Zealand KEYWORDS form, and in the Philippines, the conversion plant and the electricity market had both been the responsibility of NAPOCOR Figure Geothermal. Power Plant, Contracts. BOT, BOO illustrates this ABSTRACT This paper describes the process whereby PNOC-EDC, as resource developer and host utility, established a number of Build, Operate, Transfer (BOT) contracts for the power plants involved in the Leyte Geothermal Power Project. It the project itself and PNOC-EDC NAPOCOR describes some of the issues involved in selecting the strategy for establishing the contracts The bidding, evaluation and award processes are outlined and a number of lessons are drawn from the 1 Geothermal in Philippine experience gained, these lessons being of significance both hosts and prospective private sector developers. It concludes that the establishment of the contracts has been well executed and For the agreed development at Leyte, the power plant component emphasises that maintaining a very short timetable for bidding is a would be undertaken by However, the capital definite advantage. investment required (initially estimated as being of the order of US$ 700 million in addition the resource and developments) BACKGROUND was much to be undertaken on a self basis, and it was therefore decided to seek external participation by private sector Initial surface exploration of the Leyte geothermal resources power plant developerdoperators. commenced in 1972, and the Tongonan geothermal project came on line in 1983, using the lower Mahiao and Sambaloran sectors of In the case of a private sector involvement in the power plant, the the Mahiao reservoir. -

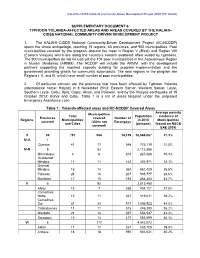

Supplementary Document 6: Typhoon Yolanda-Affected Areas and Areas Covered by the Kalahi– Cidss National Community-Driven Development Project

KALAHI–CIDSS National Community-Driven Development Project (RRP PHI 46420) SUPPLEMENTARY DOCUMENT 6: TYPHOON YOLANDA-AFFECTED AREAS AND AREAS COVERED BY THE KALAHI– CIDSS NATIONAL COMMUNITY-DRIVEN DEVELOPMENT PROJECT 1. The KALAHI–CIDDS National Community-Driven Development Project (KC-NCDDP) spans the whole archipelago, reaching 15 regions, 63 provinces, and 900 municipalities. Poor municipalities covered by the program abound the most in Region V (Bicol) and Region VIII (Eastern Visayas) which are along the country’s eastern seaboard often visited by typhoons. The 900 municipalities do not include yet the 104 poor municipalities in the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM). The NCDDP will include the ARMM, with the development partners supporting the required capacity building for program implementation and the government providing grants for community subprojects. The new regions in the program are Regions I, II, and III, which have small number of poor municipalities. 2. Of particular concern are the provinces that have been affected by Typhoon Yolanda (international name: Haiyan) in 8 November 2013: Eastern Samar, Western Samar, Leyte, Southern Leyte, Cebu, Iloilo, Capiz, Aklan, and Palawan, and by the Visayas earthquake of 15 October 2013: Bohol and Cebu. Table 1 is a list of areas targeted under the proposed Emergency Assistance Loan. Table 1: Yolanda-affected areas and KC-NCDDP Covered Areas Average poverty Municipalities Total Population incidence of Provinces covered Number of Regions Municipalities in 2010 Municipalities -

Occs and Bccs with Microsoft Office 365 Accounts1

List of OCCs and BCCs with Microsoft Office 365 Accounts1 COURT/STATION ACCOUNT TYPE EMAIL ADDRESS RTC OCC Caloocan City OCC [email protected] METC OCC Caloocan City OCC [email protected] RTC OCC Las Pinas City OCC [email protected] METC OCC Las Pinas City OCC [email protected] RTC OCC Makati City OCC [email protected] METC OCC Makati City OCC [email protected] RTC OCC Malabon City OCC [email protected] METC OCC Malabon City OCC [email protected] RTC OCC Mandaluyong City OCC [email protected] METC OCC Mandaluyong City OCC [email protected] RTC OCC Manila City OCC [email protected] METC OCC Manila City OCC [email protected] RTC OCC Marikina City OCC [email protected] METC OCC Marikina City OCC [email protected] 1 to search for a court or email address, just click CTRL + F and key in your search word/s RTC OCC Muntinlupa City OCC [email protected] METC OCC Muntinlupa City OCC [email protected] RTC OCC Navotas City OCC [email protected] METC OCC Navotas City OCC [email protected] RTC OCC Paranaque City OCC [email protected] METC OCC Paranaque City OCC [email protected] RTC OCC Pasay City OCC [email protected] METC OCC Pasay City OCC [email protected] RTC OCC Pasig City OCC [email protected] METC OCC Pasig City OCC [email protected] RTC OCC Quezon City OCC [email protected] METC OCC -

13. Inventory and Assessment of Mother Trees of Indigenous Timber Species on Leyte Island and Southern Mindanao, the Philippines

13. INVENTORY AND ASSESSMENT OF MOTHER TREES OF INDIGENOUS TIMBER SPECIES ON LEYTE ISLAND AND SOUTHERN MINDANAO, THE PHILIPPINES Nestor Gregorio, Urbano Doydora, Steve Harrison, John Herbohn and Jose Sebua The scarcity of information about the distribution and phenology of superior mother trees is a major constraint in scaling up the production of high quality seedlings of native timber trees in the Philippines. There is also a lack of knowledge among seedling producers and seed collectors about the ideal characteristics of superior mother trees resulting in the collection of germplasm from low quality sources. A survey to identify the location and phenology and to assess the phenotypic quality of mother trees of native timber species on Leyte Island was carried out as part of the implementation of the ACIAR Q-Seedling Project. A similar survey was also undertaken in Southern Mindanao as an offshoot of the Q-seedling project implementation and to support the reforestation program of Sagittarius Mines Incorporated. Locations of mother trees were recorded using a global positioning system and phenologies were determined through local knowledge of seedling producers and available literature. Phenotypic quality was assessed using the method developed by the Department of Environment and Natural Resources. On Leyte Island, 502 mother trees belonging to 32 species were identified. However, almost half of the identified mother trees were of low physical quality, with bent, forking and eccentric stems. In Southern Mindanao, 763 trees belonging to 117 species were identified from the natural forest and on-farm sites. There is a need for an information campaign on the importance of germplasm quality and capacity building to encourage seedling producers to adopt the germplasm collection protocol to increase the collection and use of high quality germplasm. -

I Had Well Over 1000 Hours of Time in the Air Before I

“I had well over 1,000 hours of time in the air before I entered combat. Most of that was as an instrument instructor fl ying the SNJ. Instrument fl ying really teaches you the fi ner points of fl ying an airplane. It also makes you focus and for some reason I found that it carried over to gunnery work in the Hellcat as well. Every time I got behind a Japanese airplane I was very focused as my bullets tore into them!” —Lin Lindsay Joining the fi ght I joined VF-19 “Satan’s Kittens” as one of its founding members in August of 1943. We gathered at Los Alamitos, California, and “Fighting Nineteen” was supplied with a paltry sum of airplanes; an SNJ, a JF2 Duck, a Piper Cub, and a single F6F-3 Hellcat. Most of them were not much to write home about as far as fi ghters go except of course, the F6F. To me, the Hellcat was a thing of beauty. It was Grumman made and damn near inde- structible! As a gun platform it was hard hit- ting with six .50 caliber machine guns in the wings, bulletproof glass up front and armor protection for the pilot. It was certainly bet- ter than anything the Japanese had, especially with self-sealing gas tanks, better radios, bet- ter fi repower and better trained pilots. 24 fl ightjournal.com Bad Kitty.indd 24 5/10/13 11:51 AM Bad KittyVF-19 “Satan’s Kittens” Chew Up the Enemy BY ELVIN “LIN” LINDSAY, LT. -

Manila American Cemetery and Memorial

Manila American Cemetery and Memorial American Battle Monuments Commission - 1 - - 2 - - 3 - LOCATION The Manila American Cemetery is located about six miles southeast of the center of the city of Manila, Republic of the Philippines, within the limits of the former U.S. Army reservation of Fort William McKinley, now Fort Bonifacio. It can be reached most easily from the city by taxicab or other automobile via Epifanio de los Santos Avenue (Highway 54) and McKinley Road. The Nichols Field Road connects the Manila International Airport with the cemetery. HOURS The cemetery is open daily to the public from 9:00 am to 5:00 pm except December 25 and January 1. It is open on host country holidays. When the cemetery is open to the public, a staff member is on duty in the Visitors' Building to answer questions and escort relatives to grave and memorial sites. HISTORY Several months before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, a strategic policy was adopted with respect to the United States priority of effort, should it be forced into war against the Axis powers (Germany and Italy) and simultaneously find itself at war with Japan. The policy was that the stronger European enemy would be defeated first. - 4 - With the surprise Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941 and the bombing attacks on 8 December on Wake Island, Guam, Hong Kong, Singapore and the Philippine Islands, the United States found itself thrust into a global war. (History records the other attacks as occurring on 8 December because of the International Date Line. -

Oral History Essay Components

Oral History Essay Components Comment [kwl1]: Format: In bold, give rank and I. Sample Introductions full name of veteran Comment [kwl2]: Format: List their unit (from smallest to largest) below their name (or Civilian + Sample #1: War) Coxswain Daniel Folsom Comment [kwl3]: Content: This intro paragraph 111th Battalion NCB, U.S. Navy combines information about the veteran and a specific memorable event (see the components sheet) “…Going into Normandy was a very moving experience. Seeing so many kids my age…that was Comment [KL4]: Content & style: Used a direct their last day. It was very hard to do that.” Like so many of his young comrades, Daniel Folsom was only quote from anecdote to “hook” the reader. th Comment [KL5]: Content: By using the nineteen years old when the invasion of Normandy took place on the 6 of June, 1944. After being information on the bio sheet, it is possible to drafted into the Navy in the fall of 1942, Folsom became a coxswain1 on a rhino barge where he spent calculate the veteran’s age at a given time during their service. Here, knowing that he was only 19 four years in service of the 111th Battalion NCB. His battalion was the only battalion in the Navy to fight years old adds historical context as well as interest for the reader. in every continent that was fought on during World War II. Comment [KL6]: Organization: In your intro paragraph, add an endnote to indicate the veteran’s [During my service] I went to Europe…. I was in Normandy on June the 6th, and came name and date of the interview.