Youtube Vs. the Music Industry: Are Online Service Providers Doing Enough to Prevent Piracy?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uila Supported Apps

Uila Supported Applications and Protocols updated Oct 2020 Application/Protocol Name Full Description 01net.com 01net website, a French high-tech news site. 050 plus is a Japanese embedded smartphone application dedicated to 050 plus audio-conferencing. 0zz0.com 0zz0 is an online solution to store, send and share files 10050.net China Railcom group web portal. This protocol plug-in classifies the http traffic to the host 10086.cn. It also 10086.cn classifies the ssl traffic to the Common Name 10086.cn. 104.com Web site dedicated to job research. 1111.com.tw Website dedicated to job research in Taiwan. 114la.com Chinese web portal operated by YLMF Computer Technology Co. Chinese cloud storing system of the 115 website. It is operated by YLMF 115.com Computer Technology Co. 118114.cn Chinese booking and reservation portal. 11st.co.kr Korean shopping website 11st. It is operated by SK Planet Co. 1337x.org Bittorrent tracker search engine 139mail 139mail is a chinese webmail powered by China Mobile. 15min.lt Lithuanian news portal Chinese web portal 163. It is operated by NetEase, a company which 163.com pioneered the development of Internet in China. 17173.com Website distributing Chinese games. 17u.com Chinese online travel booking website. 20 minutes is a free, daily newspaper available in France, Spain and 20minutes Switzerland. This plugin classifies websites. 24h.com.vn Vietnamese news portal 24ora.com Aruban news portal 24sata.hr Croatian news portal 24SevenOffice 24SevenOffice is a web-based Enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems. 24ur.com Slovenian news portal 2ch.net Japanese adult videos web site 2Shared 2shared is an online space for sharing and storage. -

Trump Is Still Banned on Youtube. Now the Clock Is Ticking. - WSJ

5/8/2021 Trump Is Still Banned on YouTube. Now the Clock Is Ticking. - WSJ This copy is for your personal, non-commercial use only. To order presentation-ready copies for distribution to your colleagues, clients or customers visit https://www.djreprints.com. https://www.wsj.com/articles/trump-is-still-banned-on-youtube-that-could-change-11620293402 TECH Trump Is Still Banned on YouTube. Now the Clock Is Ticking. The video-sharing giant says it is continuing to monitor threat of violence in wake of Jan. 6 Capitol riot Former President Donald Trump has been suspended from posting on YouTube since January. PHOTO: YURI GRIPASPOOLSHUTTERSTOCK By Tripp Mickle Updated May 6, 2021 1115 am ET Listen to this article 6 minutes With Donald Trump’s return to Facebook in limbo, YouTube has emerged as the former president’s best chance to return to social media in the near future. Mr. Trump has been suspended from posting on the video-sharing service owned by Alphabet Inc.’s GOOG 0.73% ▲ Google since January. Company leaders have said they will revisit their decision but have given few details on when, or who will make the call. Unlike Facebook Inc. and Twitter Inc., which has permanently banned Mr. Trump, YouTube has provided limited information on its call. Facebook first explained its ban in a personal post by Chief Executive Mark Zuckerberg and then referred the matter to its https://www.wsj.com/articles/trump-is-still-banned-on-youtube-that-could-change-11620293402?mod=searchresults_pos10&page=1 1/5 5/8/2021 Trump Is Still Banned on YouTube. -

'Boxing Clever

NOVEMBER 05 2018 sandboxMUSIC MARKETING FOR THE DIGITAL ERA ISSUE 215 ’BOXING CLEVER SANDBOX SUMMIT SPECIAL ISSUE Event photography: Vitalij Sidorovic Music Ally would like to thank all of the Sandbox Summit sponsors in association with Official lanyard sponsor Support sponsor Networking/drinks provided by #MarketMusicBetter ast Wednesday (31st October), Music Ally held our latest Sandbox Summit conference in London. While we were Ltweeting from the event, you may have wondered why we hadn’t published any reports from the sessions on our site and ’BOXING CLEVER in our bulletin. Why not? Because we were trying something different: Music Ally’s Sandbox Summit conference in London, IN preparing our writeups for this special-edition sandbox report. From the YouTube Music keynote to panels about manager/ ASSOCIATION WITH LINKFIRE, explored music marketing label relations, new technology and in-house ad-buying, taking in Fortnite and esports, Ed Sheeran, Snapchat campaigns and topics, as well as some related areas, with a lineup marketing to older fans along the way, we’ve broken down the key views, stats and debates from our one-day event. We hope drawn from the sharp end of these trends. you enjoy the results. :) 6 | sandbox | ISSUE 215 | 05.11.2018 TALES OF THE ’TUBE Community tabs, premieres and curation channels cited as key tools for artists on YouTube in 2018 ensions between YouTube and the music industry remain at raised Tlevels following the recent European Parliament vote to approve Article 13 of the proposed new Copyright Directive, with YouTube’s CEO Susan Wojcicki and (the day after Sandbox Summit) music chief Lyor Cohen both publicly criticising the legislation. -

Youtube Yrityksen Markkinoinnin Välineenä

Lassi Tuomikoski Youtube yrityksen markkinoinnin välineenä Metropolia Ammattikorkeakoulu Tradenomi Liiketalouden koulutusohjelma Opinnäytetyö Lokakuu 2014 Tiivistelmä Tekijä Lassi Tuomikoski Otsikko Youtube yrityksen markkinoinnin välineenä Sivumäärä 47 sivua + 2 liitettä Aika 9.11.2014 Tutkinto Tradenomi Koulutusohjelma Liiketalous Suuntautumisvaihtoehto Markkinointi Ohjaaja lehtori Raisa Varsta Tämän opinnäytetyön tarkoituksena oli luoda ohjeistus oman sisällön luomiseen Youtubessa aloittelevalle yritykselle. Työn toisena tavoitteena on osoittaa, miten yritys pystyy hyödyntämään videonjakopalvelu Youtubea omassa liiketoiminnassaan muiden markkinoinnin keinojen avulla. Työn viitekehyksessä käydään läpi keskeisimmät käsitteet ja termit ja esitellään Youtube yrityksenä sekä videonjakopalveluna. Työssä kerrotaan, millä eri tavoin yritys voi näkyä Youtubessa ja Youtube yrityksen markkinoinnissa. Toiminnallisena osana työtä tuotettiin konkreettisten esimerkkien pohjalta ohjeistus Youtuben parissa aloittelevalle yritykselle siitä, kuinka päästä alkuun tehokkaassa ja yritykselle lisäarvoa tuottavassa sisällöntuottamisessa. Mitä asiota oman sisällön luomisessa täytyy ottaa huomioon ja millä keinoilla Youtubessa voidaan menestyä. Opinnäytetyön johtopäätöksenä todettiin, että ennen oman sisällön luomista on yrityksen sisältöstrategian oltava kunnossa. Sisällön tärkeyttä ei voi oman sisällön luomisessa tarpeeksi korostaa. Sisällön on oltava merkityksellistä asiakkaan kannalta. Avainsanat youtube, sisältömarkkinointi, sosiaalinen media Abstract -

Value of Youtube to the Music Industry - Paper III - Promotion

Value of YouTube to the music industry - Paper III - Promotion June 2017 RBB Economics 1 1 Introduction The music industry has undergone significant change over the past few years, with declining volumes of music sold through an ownership model (such as downloads) and rapid growth in usage models (such as streaming).1 While many services provide value to the recorded music industry, in the 12 months to December 2016 one video streaming platform, YouTube, paid out over USD 1 billion to the music industry from advertising alone.2 YouTube claims that not only does it return money directly to creators, but also that it has a promotional effect on music.3 However, some commentators argue that YouTube has a negative impact on the music industry: paying insufficiently for content and cannibalising other services. RBB Economics has undertaken several empirical analyses in order to evaluate YouTube’s potential promotional or cannibalisation effects on the music industry in Europe. We analyse the results from 1,500 person user surveys carried out in each of four European countries, as well as data on YouTube views and streams on audio platforms of over 8,000 tracks across these countries over a three year period.4 In our first note we considered the evidence of cannibalisation by YouTube of other legitimate music services. ● Looking at survey evidence we found that significant cannibalisation is unlikely: users of music on YouTube are primarily lighter users, and if music videos were no longer shown on YouTube, 85% of users’ time would be lost or shifted to lower or similar value channels, and even to file sharing or piracy. -

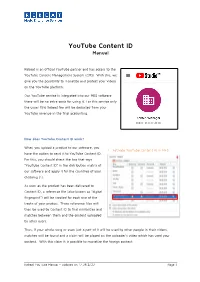

Manual Youtube Content ID

YouTube Content ID Manual Rebeat is an official YouTube partner and has access to the YouTube Content Management System (CMS). With this, we give you the possibility to monetize and protect your videos on the YouTube platform. Our YouTube service is integrated into our MES software – there will be no extra costs for using it. For this service only the usual 15% Rebeat fee will be deducted from your YouTube revenue in the final accounting. How does YouTube Content ID work? When you upload a product to our software, you 1. Activate YouTube Content ID in MES have the option to send it to YouTube Content ID. For this, you should check the box that says “YouTube Content ID” in the distribution matrix of our software and apply it for the countries of your choosing (1). As soon as the product has been delivered to Content ID, a reference file (also known as “digital fingerprint”) will be created for each one of the tracks of your product. These reference files will then be used by Content ID to find similarities and matches between them and the content uploaded by other users. Thus, if your whole song or even just a part of it will be used by other people in their videos, matches will be found and a claim will be placed on the uploader’s video which has used your content. With this claim it is possible to monetize the foreign content. Rebeat YouTube Manual – updated on 17.08.2020 Page 1 With the help of Content ID we can also claim any of your content manually. -

You(Tube), Me, and Content ID: Paving the Way for Compulsory Synchronization Licensing on User-Generated Content Platforms Nicholas Thomas Delisa

Brooklyn Law Review Volume 81 | Issue 3 Article 8 2016 You(Tube), Me, and Content ID: Paving the Way for Compulsory Synchronization Licensing on User-Generated Content Platforms Nicholas Thomas DeLisa Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/blr Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons, and the Internet Law Commons Recommended Citation Nicholas T. DeLisa, You(Tube), Me, and Content ID: Paving the Way for Compulsory Synchronization Licensing on User-Generated Content Platforms, 81 Brook. L. Rev. (2016). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/blr/vol81/iss3/8 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Law Review by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. You(Tube), Me, and Content ID PAVING THE WAY FOR COMPULSORY SYNCHRONIZATION LICENSING ON USER- GENERATED CONTENT PLATFORMS INTRODUCTION Ever wonder about how the law regulates your cousin’s wedding video posted on her YouTube account? Most consumers do not ponder questions such as “Who owns the content in my video?” or “What is a fair use?” or “Did I obtain the proper permission to use Bruno Mars’s latest single as the backing track to my video?” These are important questions of law that are answered each day on YouTube1 by a system called Content ID.2 Content ID identifies uses of audio and visual works uploaded to YouTube3 and allows rights holders to collect advertising revenue on that content through the YouTube Partner Program.4 It is easy to see why Content ID was implemented—300 hours of video are uploaded to YouTube per minute.5 Over six billion hours of video are watched each month on YouTube (almost an hour for every person on earth),6 and it is unquestionably the most popular streaming video site on the Internet.7 Because of the staggering amount of content 1 See A Guide to YouTube Removals,ELECTRONIC fRONTIER fOUND., https://www.eff.org/issues/intellectual-property/guide-to-youtube-removals [http://perma.cc/ BF4Y-PW6E] (last visited June 6, 2016). -

The Musicless Music Video As a Spreadable Meme Video: Format, User Interaction, and Meaning on Youtube

International Journal of Communication 11(2017), 3634–3654 1932–8036/20170005 The Musicless Music Video as a Spreadable Meme Video: Format, User Interaction, and Meaning on YouTube CANDE SÁNCHEZ-OLMOS1 University of Alicante, Spain EDUARDO VIÑUELA University of Oviedo, Spain The aim of this article is to analyze the musicless music video—that is, a user-generated parodic musicless of the official music video circulated in the context of online participatory culture. We understand musicless videos as spreadable content that resignifies the consumption of the music video genre, whose narrative is normally structured around music patterns. Based on the analysis of the 22 most viewed musicless videos (with more than 1 million views) on YouTube, we aim, first, to identify the formal features of this meme video format and the characteristics of the online channels that host these videos. Second, we study whether the musicless video generates more likes, dislikes, and comments than the official music video. Finally, we examine how the musicless video changes the multimedia relations of the official music video and gives way to new relations among music, image, and text to generate new meanings. Keywords: music video, music meme, YouTube, participatory culture, spreadable media, interaction For the purposes of this research, the musicless video is considered as a user-generated memetic video that alters and parodies an official music video and is spread across social networks. The musicless video modifies the original meaning of the official-version music video, a genre with one of the greatest impacts on the transformation of the audiovisual landscape in the past 10 years. -

Android App for Free Music Downloads Top 10 Free Music Download Apps for Android to Download Free Music

android app for free music downloads Top 10 Free Music Download Apps for Android to Download Free Music. Along with the rapid development of internet and Smartphone, you can handily enjoy your favorite music on mobile devices at any time, rather than listen to music with your old CD or MP3 player. Just a music app on your phone, can totally replace all your music devices. However, nowadays, you may easily find out that lots of free music download apps for Android no longer enable you to download songs free. No matter how deep you love music, you won't pay money for every song you like and downloaded. Because you like all kinds of music types, you fancy too many singers. So many times, free music download apps for Android can be the biggest saviors for you. In this article, we will show you 10 great Android apps for you to free stream and download mp3 songs. Let's look at the top free music apps for Android to download free music. 1. Gaana Music - One-stop solution music download app for Android. Gaana is an excellent free music downloading app on Android for you to download music for free. It provides you with free and unlimited access to all your favorite songs, no matter where you are. Based on the India's largest online music broadcasting service, Gaana can be the one-stop solution for all your music needs. Gaana carries huge collection of Bollywood movie songs. So if you like listening to Hindi music, it can be your best choice to free download MP3 songs. -

The Power of You in Youtube

HA RNESSING THE POWER OF " YOU" IN YouTube How just one word - "YOU" - can double your YouTube viewership Writ t en and Researched by Dane Golden and Phil St arkovich a st udy by and .com HARNESSING THE POWER OF "YOU" IN YOUTUBE - A TUBEBUDDY/ HEY.COM STUDY - Published Feb. 7, 2017 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY HINT: IT'S NOT ME, IT'S "YOU" various ways during the first 30 platform. But it's more likely that "you" is seconds versus videos that did not say a measurable result of videos that are This study is all about YouTube and "YOU." "you" at all in that period. focused on engaging the audience rather than only talking about the subject of the After extensive research, we've found that saying These findings show a clear advantage videos. YouTube is a personal, social video the word "you" just once in the first 5 seconds of for videos that begin with a phrase platform, and the channels that recognize a YouTube video can increase overall views by such as: "Today I'm going to show you and utilize this factor tend to do better. 66%. And views can increase by 97% - essentially how to improve your XYZ." doubling the viewcount - if "you" is said twice in Importantly, this study shows video the first 5 seconds (see table on page 22). While the word "you" is not a silver creators and businesses how to make bullet to success on YouTube, when more money with YouTube. With the word And "you" affects more than YouTube views. We used in context as a part of otherwise "you," YouTubers can double their also learned that simply saying "you" just once in helpful or interesting videos, combined advertising revenue, ecommerce the first 5 seconds of a video is likely to increase with a channel optimization strategy, companies can drive more website clicks, likes per view by approximately 66%, and overall saying "you" has been proven to apps can drive more downloads, and B2B engagements per view by about 68%. -

Marketing Plan

ALLIED ARTISTS MUSIC GROUP An Allied Artists Int'l Company MARKETING & PROMOTION MARKETING PLAN: ROCKY KRAMER "FIRESTORM" Global Release Germany & Rest of Europe Digital: 3/5/2019 / Street 3/5/2019 North America & Rest of World Digital: 3/19/2019 / Street 3/19/2019 MASTER PROJECT AND MARKETING STRATEGY 1. PROJECT GOAL(S): The main goal is to establish "Firestorm" as an international release and to likewise establish Rocky Kramer's reputation in the USA and throughout the World as a force to be reckoned with in multiple genres, e.g. Heavy Metal, Rock 'n' Roll, Progressive Rock & Neo-Classical Metal, in particular. Servicing and exposure to this product should be geared toward social media, all major radio stations, college radio, university campuses, American and International music cable networks, big box retailers, etc. A Germany based advance release strategy is being employed to establish the Rocky Kramer name and bona fides within the "metal" market, prior to full international release.1 2. OBJECTIVES: Allied Artists Music Group ("AAMG"), in association with Rocky Kramer, will collaborate in an innovative and versatile marketing campaign introducing Rocky and The Rocky Kramer Band (Rocky, Alejandro Mercado, Michael Dwyer & 1 Rocky will begin the European promotional campaign / tour on March 5, 2019 with public appearances, interviews & live performances in Germany, branching out to the rest of Europe, before returning to the U.S. to kick off the global release on March 19, 2019. ALLIED ARTISTS INTERNATIONAL, INC. ALLIED ARTISTS MUSIC GROUP 655 N. Central Ave 17th Floor Glendale California 91203 455 Park Ave 9th Floor New York New York 10022 L.A. -

SCMS 2019 Conference Program

CELEBRATING SIXTY YEARS SCMS 1959-2019 SCMSCONFERENCE 2019PROGRAM Sheraton Grand Seattle MARCH 13–17 Letter from the President Dear 2019 Conference Attendees, This year marks the 60th anniversary of the Society for Cinema and Media Studies. Formed in 1959, the first national meeting of what was then called the Society of Cinematologists was held at the New York University Faculty Club in April 1960. The two-day national meeting consisted of a business meeting where they discussed their hope to have a journal; a panel on sources, with a discussion of “off-beat films” and the problem of renters returning mutilated copies of Battleship Potemkin; and a luncheon, including Erwin Panofsky, Parker Tyler, Dwight MacDonald and Siegfried Kracauer among the 29 people present. What a start! The Society has grown tremendously since that first meeting. We changed our name to the Society for Cinema Studies in 1969, and then added Media to become SCMS in 2002. From 29 people at the first meeting, we now have approximately 3000 members in 38 nations. The conference has 423 panels, roundtables and workshops and 23 seminars across five-days. In 1960, total expenses for the society were listed as $71.32. Now, they are over $800,000 annually. And our journal, first established in 1961, then renamed Cinema Journal in 1966, was renamed again in October 2018 to become JCMS: The Journal of Cinema and Media Studies. This conference shows the range and breadth of what is now considered “cinematology,” with panels and awards on diverse topics that encompass game studies, podcasts, animation, reality TV, sports media, contemporary film, and early cinema; and approaches that include affect studies, eco-criticism, archival research, critical race studies, and queer theory, among others.