Evensong Live 2019 Anthems and Canticles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

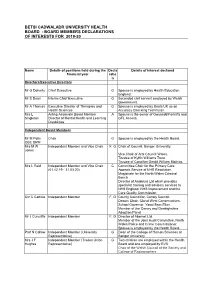

Board Members Declarations of Interests for 2019-20

BETSI CADWALADR UNIVERSITY HEALTH BOARD - BOARD MEMBERS DECLARATIONS OF INTERESTS FOR 2019-20 Name Details of positions held during the Decla Details of interest declared financial year ratio n Directors/Executive Directors Mr G Doherty Chief Executive G Spouse is employed by Health Education England. Mr S Dean Interim Chief Executive G Seconded civil servant employed by Welsh Government. Mr A Thomas Executive Director of Therapies and G Spouse is employed by Boots UK as an Health Sciences Accuracy Checking Technician. Mrs L Acting Associate Board Member A Spouse is the owner of Gwynedd Forklifts and Singleton Director of Mental Health and Learning GFL Access. Disabilities Independent Board Members Mr M Polin Chair G Spouse is employed by the Health Board. OBE QPM Mrs M W Independent Member and Vice Chair F, G Chair of Council, Bangor University. Jones Vice Chair of Arts Council Wales. Trustee of Kyffin Williams Trust. Trustee of Canolfan Gerdd William Mathias. Mrs L Reid Independent Member and Vice Chair C Committee Chair for the Primary Care (01.12.19 - 31.03.20) Appeals Service of NHS Resolution. Magistrate for the North Wales Criminal Bench Director of Anakrisis Ltd which provides specialist training and advisory services to NHS England, NHS Improvement and the Care Quality Commission Cllr C Carlisle Independent Member F, G County Councillor, Conwy Council. Deputy Chair, Clwyd West Conservatives. School Governor, Ysgol Bryn Elian. Member of the Conwy and Denbighshire Adoption Panel Mr J Cuncliffe Independent Member F, G Director of Abernet Ltd. Member of the Joint Audit Committee, North Wales Police and Crime Commissioner. -

DANCING DAY MUSIC FORCHRISTMAS FIFTH AVENUE,NEWYORK JOHN SCOTT CONDUCTOR Matthew Martin (B

DANCING DAY MUSIC FOR CHRISTMAS SAINT THOMAS CHOIR OF MEN & BOYS, FIFTH AVENUE, NEW YORK JOHN SCOTT CONDUCTOR RES10158 Matthew Martin (b. 1976) John Rutter (b. 1945) Dancing Day 1. Novo profusi gaudio [3:36] Dancing Day Part 1 Music for Christmas Patrick Hadley (1899-1973) 17. Prelude [3:35] 2. I sing of a maiden [2:55] 18. Angelus ad virginem [1:55] 19. A virgin most pure [5:04] Benjamin Britten (1913-1976) 20. Personent hodie [1:57] A Ceremony of Carols, Op. 28 Part 2 Saint Thomas Choir of Men & Boys, Fifth Avenue, New York 3. Procession [1:32] 21. Interlude [4:05] 4. Wolcum Yole! [1:24] 22. There is no rose [1:53] 3-15 & 17-24 5. There is no Rose [2:26] 23. Coventry Carol [3:54] Sara Cutler harp [1:46] 1 & 16 6. That yonge child 24. Tomorrow shall be my Stephen Buzard organ 7. Balulalow [1:21] dancing day [3:03] Benjamin Sheen organ 2 & 25-26 8. As dew in Aprille [1:02] 9. This little babe [1:30] Traditional English 10. Interlude [3:32] arr. Philip Ledger (1937-2012) John Scott conductor 11. In Freezing Winter Night [3:50] 25. On Christmas Night [2:00] 12. Spring Carol [1:14] (Sussex Carol) 13. Adam lay i-bounden [1:12] 14. Recession [1:37] William Mathias (1934-1992) [1:41] 26. Wassail Carol Benjamin Britten 15. A New Year Carol [2:19] Total playing time [63:58] Traditional Dutch arr. John Scott (b. 1956) About the Saint Thomas Choir of Men & Boys: 16. -

New Head for Hawford, OV Artists, Stephen Cleobury Concert & A

N ew Head for Hawford, OV Artists, Stephen Cleobury concert & a tribute to Cecil Duckworth Announcement of New Head at King’s Hawford The Headmaster and Governors of The King’s School, Worcester are delighted to announce the appointment of Mrs Jennie Phillips as the new Head of King’s Hawford, one of Worcester’s leading 2 – 11 Prep Schools. Jennie will join in April 2021 from Monmouth School Girls’ Prep School where she is currently the Head. She was appointed from a dynamic field of sitting Heads and Deputies, and was the unanimous choice of the Headmaster, Governors and the staff who met her. Jennie was educated at Oxford High School, and read Education at the University of Exeter. A keen hiker and swimmer, Jennie is married to Eddie and they have two daughters, Amelia and Daisy, who are all excited about the move. Reflecting on her appointment, Mrs Phillips said, “I am absolutely delighted to be joining the team at King’s Hawford. The school has a wonderful warmth and a sense of community which is clearly held dear by parents, staff and pupils alike. I very much look forward to getting to know the school community and building on the excellent work of Mr Jim Turner, whilst working closely with Mr Richard Chapman, Head of King’s St Albans, under the Head of our Foundation, Mr Gareth Doodes. We will work together to provide parents with the choice of two outstanding, vibrant Prep school learning environments with high aspirations, that prepare our pupils well for the next step in their journey as they move on to King’s Worcester at the age 11.” The Headmaster of the King’s Foundation, Gareth Doodes, celebrated Jennie’s appointment. -

Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected]

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2016 Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Van Oort, Danielle, "Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal" (2016). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 1016. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. REST, SWEET NYMPHS: PASTORAL ORIGINS OF THE ENGLISH MADRIGAL A thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music Music History and Literature by Danielle Van Oort Approved by Dr. Vicki Stroeher, Committee Chairperson Dr. Ann Bingham Dr. Terry Dean, Indiana State University Marshall University May 2016 APPROVAL OF THESIS We, the faculty supervising the work of Danielle Van Oort, affirm that the thesis, Rest Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal, meets the high academic standards for original scholarship and creative work established by the School of Music and Theatre and the College of Arts and Media. This work also conforms to the editorial standards of our discipline and the Graduate College of Marshall University. With our signatures, we approve the manuscript for publication. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to express appreciation and gratitude to the faculty and staff of Marshall University’s School of Music and Theatre for their continued support. -

The Pelican Record Corpus Christi College Vol

The Pelican Record Corpus Christi College Vol. LV December 2019 The Pelican Record The President’s Report 4 Features 10 Ruskin’s Vision by David Russell 10 A Brief History of Women’s Arrival at Corpus by Harriet Patrick 18 Hugh Oldham: “Principal Benefactor of This College” by Thomas Charles-Edwards 26 The Building Accounts of Corpus Christi College, Oxford, 1517–18 by Barry Collett 34 The Crew That Made Corpus Head of the River by Sarah Salter 40 Richard Fox, Bishop of Durham by Michael Stansfield 47 Book Reviews 52 The Renaissance Reform of the Book and Britain: The English Quattrocento by David Rundle; reviewed by Rod Thomson 52 Anglican Women Novelists: From Charlotte Brontë to P.D. James, edited by Judith Maltby and Alison Shell; reviewed by Emily Rutherford 53 In Search of Isaiah Berlin: A Literary Adventure by Henry Hardy; reviewed by Johnny Lyons 55 News of Corpuscles 59 News of Old Members 59 An Older Torpid by Andrew Fowler 61 Rediscovering Horace by Arthur Sanderson 62 Under Milk Wood in Valletta: A Touch of Corpus in Malta by Richard Carwardine 63 Deaths 66 Obituaries: Al Alvarez, Michael Harlock, Nicholas Horsfall, George Richardson, Gregory Wilsdon, Hal Wilson 67-77 The Record 78 The Chaplain’s Report 78 The Library 80 Acquisitions and Gifts to the Library 84 The College Archives 90 The Junior Common Room 92 The Middle Common Room 94 Expanding Horizons Scholarships 96 Sharpston Travel Grant Report by Francesca Parkes 100 The Chapel Choir 104 Clubs and Societies 110 The Fellows 122 Scholarships and Prizes 2018–2019 134 Graduate -

Visual Art in the English Parish Church Since 1945

Peter Webster Institute of Historical Research Visual art in the English parish church since 1945 [One of a series of short articles contributed to the DVD-ROM The English Parish Church (York, Centre for the Study of Christianity and Culture, 2010).1] Even the most fleeting of tours of the English cathedrals in the present day would give an observer the impression that the Church of England was a major patron of contemporary art. Commissions, competitions and exhibitions abound; at the time of writing Chichester cathedral is in the process of commissioning a major new work, and the shortlist of artists includes figures of the stature of Mark Wallinger and Antony Gormley. It is less well known that this activity is in fact a relatively recent phenomenon. In the early 1930s, by contrast, it was widely thought (amongst those clergy, artists and critics who thought about such things) that there was, in the strictest sense, no art at all in English churches. Of course, the medieval cathedrals and parish churches contained many exquisite examples of the art of their time. The nineteenth century had seen a massive boom in urban church building in the revived Gothic style, with attendant furnishings and decoration. However, the vast bulk of the stained glass, ornaments and church plate of the more recent past was regarded as hopelessly derivative at best, and of poor workmanship at worst. The sculptor Henry Moore wrote of the ‘affected and sentimental prettiness’ of much of the church art of his time. One director of the Tate Gallery argued that if the contents of churches were the only evidence available, ‘our civilisation would be found shallow, vulgar, timid and complacent, the meanest there has ever been.’ Much research remains to be done on that nineteenth century heritage, to determine how justly such charges were laid against it. -

Trinity Choral Services:Choral Services 2

Trinity College Chapel Choral Services & Anthem Texts Lent Term 2010 Sundays COLLEGE COMMUNION 10.00 a.m. COLLEGE EVENSONG WITH ADDRESS 6.15 p.m. Tuesdays EVENSONG 6.15 p.m. Thursdays EVENSONG 6.15 p.m. Tuesday 2nd February: Sung Eucharist for Candlemas 10.55 a.m. Ash Wednesday 17th February: Holy Communion & Imposition of Ashes 6.15 p.m. Holy Communion is celebrated each Wednesday lunchtime 12.30 p.m. Morning Prayer is said each weekday (except Friday) and Saturday morning 8.45 a.m. Holy Communion is celebrated each Friday morning during term 8.00 a.m. Evening Prayer is said on Monday and Wednesday evenings 6.15 p.m. The Reverend Dr Michael Banner Dean of Chapel Stephen Layton Director of Music The Reverend Alice Goodman Chaplain The Reverend Christopher Stoltz Chaplain Michael Waldron, Simon Bland Organ Scholars JANUARY 17 The Second Sunday after Epiphany 10:00 am College Communion Hymn 377: St Denio (Welsh melody / Roberts) Mass (MacMillan) 1st Lesson Isaiah 62: 1-5 Hymn 367 (i): Capetown (Filitz) Gospel John 2: 1-11 Preacher The Dean of Chapel Hymn 141: Salisbury (Howells) Hymn 484, omitting *: Aurelia (Wesley) Voluntary March (Choveaux) 5:40 pm Organ Music Before Evensong Stephen Cleobury (King’s College) Prelude and Fugue in c, BWV 546 (Bach) Sei gegrüßet, Jesu gütig, BWV 768 (Bach) 6:15 pm College Evensong Responses (McWilliam) Psalm 89: 1-8 Magnificat Primi toni (Victoria) Nunc Dimittis Double Choir (Holst) Anthem This worldes joie (Bax) Hymn 47: Dix (Kocher / Monk) Preacher Professor Amartya Sen, formerly Master of Trinity Hymn 49 (i): Wessex (Surplice) Voluntary Fantasia and Fugue in c, BWV 537 (Bach) 19 Tuesday 6:15 pm Choral Evensong Joint Service with the Choir of King’s School Ely Voluntary Postlude in G (Stanford) Introit Justorum animæ (Stanford) Responses (Rose) Psalm 150 1st Lesson Amos 7: 1-17 Canticles Service in C (Stanford) 2nd Lesson 1 Corinthians 6: 12-end Anthem Te lucis ante terminum (Balfour Gardiner) Hymn 413: Nun danket (Crüger / Mendelssohn) Final Responses (Rose) Voluntary Symphony No. -

LCOM182 Lent & Eastertide

LITURGICAL CHORAL AND ORGAN MUSIC Lent, Holy Week, and Eastertide 2018 GRACE CATHEDRAL 2 LITURGICAL CHORAL AND ORGAN MUSIC GRACE CATHEDRAL SAN FRANCISCO LENT, HOLY WEEK, AND EASTERTIDE 2018 11 MARCH 11AM THE HOLY EUCHARIST • CATHEDRAL CHOIR OF MEN AND BOYS LÆTARE Introit: Psalm 32:1-6 – Samuel Wesley Service: Collegium Regale – Herbert Howells Psalm 107 – Thomas Attwood Walmisley O pray for the peace of Jerusalem - Howells Drop, drop, slow tears – Robert Graham Hymns: 686, 489, 473 3PM CHORAL EVENSONG • CATHEDRAL CAMERATA Responses: Benjamin Bachmann Psalm 107 – Lawrence Thain Canticles: Evening Service in A – Herbert Sumsion Anthem: God so loved the world – John Stainer Hymns: 577, 160 15 MARCH 5:15PM CHORAL EVENSONG • CATHEDRAL CHOIR OF MEN AND BOYS Responses: Thomas Tomkins Psalm 126 – George M. Garrett Canticles: Third Service – Philip Moore Anthem: Salvator mundi – John Blow Hymns: 678, 474 18 MARCH 11AM THE HOLY EUCHARIST • CATHEDRAL CHOIR OF MEN AND BOYS LENT 5 Introit: Psalm 126 – George M. Garrett Service: Missa Brevis – Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina Psalm 51 – T. Tertius Noble Anthem: Salvator mundi – John Blow Motet: The crown of roses – Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Hymns: 471, 443, 439 3PM CHORAL EVENSONG • CATHEDRAL CAMERATA Responses: Thomas Tomkins Psalm 51 – Jeffrey Smith Canticles: Short Service – Orlando Gibbons Anthem: Aus tiefer Not – Felix Mendelssohn Hymns: 141, 151 3 22 MARCH 5:15PM CHORAL EVENSONG • CATHEDRAL CHOIR OF MEN AND BOYS Responses: William Byrd Psalm 103 – H. Walford Davies Canticles: Fauxbourdons – Thomas -

Lent Term 2010

KING’SCOLLEGE CAMBRIDGE CHAPELSERVICES LENTTERM HOLYWEEKANDEASTER 2010 NOT TO BE TAKEN AWAY THE USE OF CAMERAS, RECORDING EQUIPMENT, VIDEO CAMERAS AND MOBILE PHONES IS NOT PERMITTED IN CHAPEL [ 2 ] NOTICES SERMONSAND ADDRESSES 17 January Dr Edward Kessler Director Woolf Institute of Abrahamic Faiths, Cambridge; Fellow St Edmund’s College 24 January The Revd Richard Lloyd Morgan Acting Dean 31 January The Revd Abi Smetham Assistant Curate of Sheffield Manor Parish 7 February The Revd Canon Michael Hampel Acting Dean and Precentor, St Edmundsbury Cathedral 14 February The Revd Canon Anna Matthews St Albans Cathedral 21 February The Very Revd Dr John Hall Dean of Westminster 28 February The Rt Revd Dr Richard Cheetham Bishop of Kingston 7 March The Revd Canon Brian Watchorn Assistant Chaplain Maundy Thursday Professor Ellen Davies Amos Ragan Kearns Professor, Duke Divinity School, North Carolina Easter Day The Revd Richard Lloyd Morgan Acting Dean SERVICE BOOKLETS Braille and large print service booklets are available from the Chapel Administrator for Evensong and Sung Eucharist services. CHORAL SERVICES Services are normally sung by King’s College Choir on Sundays and from Tuesdays to Saturdays. Services on Mondays are sung by King’s Voices, the College’s mixed voice choir. Exceptions are listed. ORGAN RECITALS Each Saturday during term time there is an organ recital at 6.30 p.m. until 7.15 p.m. Admission is free, and there is a retiring collection. There is no recital on 16 January; the recital on 20 February will last 30 minutes and start at 6.45 p.m. following the longer Evensong that day. -

CHOIR MUSIC ANDREW NUNN (Dean)

PETER WRIGHT (Organist) STEPHEN DISLEY (Assistant Organist) FEBRUARY 2019 SOUTHWARK CATHEDRAL RACHEL YOUNG (Succentor) GILLY MYERS (Canon Precentor) CHOIR MUSIC ANDREW NUNN (Dean) DAY SERVICE RESPONSES PSALMS HYMNS SETTINGS ANTHEMS 1 Friday 5.30pm Evensong Smith 62 157 Stanford in B flat Look up, sweet babe (Lennox Berkeley) 3 SUNDAY 11.00am Eucharist 24 (7-end) 336; 44; SP 13 Missa Aeterna Christi munera O thou, the central orb (Charles Wood) CANDLEMAS (Palestrina) O nata lux (Thomas Tallis) Nunc dimittis (Dyson in F) 3.00pm Evensong Smith 132 (1-10) 156 (t. 288); CP 65 (t. 33) Stanford in A When to the temple Mary went (Johannes Eccard) 6.00pm Eucharist (Trad Rite) (men’s voices) 157; 57; 373 (t. CP 466); Missa Aeterna Christi munera Tout puissant (Francis Poulenc) 338 (Palestrina) Seigneur, je vous en prie (Francis Poulenc) 4 Monday 5.30pm Evensong Rawsthorne 4 457 (ii) Rubbra in A flat Mother of God, here I stand (John Tavener) 5 Tuesday 5.30pm Evensong Smith 9 (1-12) 346 Wise in F Hail, gladdening light (Charles Wood) 6 Wednesday 5.30pm Evensong (Cranleigh Voices) Byrd 34 373 (t. Coe Fen) Stanford in G And I saw a new heaven (Edgar Bainton) 7 Thursday 5.30pm Evensong (treble voices) Plainsong 118 (19-end) 338 (omit *) Rawsthorne in F Auf meinen lieben Gott (J. S. Bach) 8 Friday 5.30pm Evensong (men’s voices) Moore 22 245 Tonus peregrinus (Plainsong) Laudem dicite Deo (John Sheppard) 10 SUNDAY 11.00am Eucharist 138 377; CP 390; Darke in F Let all mortal flesh keep silence (Edward Bairstow) IV BEFORE 353 (omit v.3); CP 470 Ave verum corpus (William Byrd) LENT 3.00pm Evensong Shephard 2 254 (t. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Reexamining Portamento As an Expressive Resource in Choral Music, Ca. 1840-1940 a Disserta

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Reexamining Portamento as an Expressive Resource in Choral Music, Ca. 1840-1940 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts by Desiree Janene Balfour 2020 © Copyright by Desiree Janene Balfour 2020 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Reexamining Portamento as an Expressive Resource in Choral Music, ca. 1840-1940 by Desiree Janene Balfour Doctor of Musical Arts University of California, Los Angeles, 2020 Professor William A. Kinderman, Co-Chair Professor James K. Bass, Co-Chair This study reexamines portamento as an important expressive resource in nineteenth and twentieth-century Western classical choral music. For more than a half-century, portamento use has been in serious decline and its absence in choral performance is arguably an impoverishment. The issue is encapsulated by John Potter, who writes, “A significant part of the early music agenda was to strip away the vulgarity, excess, and perceived incompetence associated with bizarre vocal quirks such as portamento and vibrato. It did not occur to anyone that this might involve the rejection of a living tradition and that singers might be in denial about their own vocal past.”1 The present thesis aims to show that portamento—despite its fall from fashion—is much more than a “bizarre vocal quirk.” When blended with aspects of the modern aesthetic, 1 John Potter, "Beggar at the Door: The Rise and Fall of Portamento in Singing,” Music and Letters 87 (2006): 538. ii choral portamento is a valuable technique that can enhance the expressive qualities of a work. -

Download Album Booklet

CHRISTMAS WITH ST JOHN’S Christmas with St John’s unhurried, easy-flowing vernacular feel as Sansom’s powerful verses, and the overall For many people, the pleasures of the Christmas structure is equally effective; the melody is 1 The Shepherd’s Carol Bob Chilcott [3.40] season can be summed up in a single word: first presented by trebles alone before the 2 The Holly and the Ivy Traditional, arr. Henry Walford Davies [2.54] tradition. However, perhaps strangely for a other voices softly enter, one by one, gradually 3 Sir Christèmas William Mathias [1.33] world so steeped in the music and practices layering a serene pillow of harmonic suspensions. 4 O Oriens Cecilia McDowall [4.35] of centuries past, the English sacred choral The one fortissimo moment comes at the 5 Adam Lay ybounden Boris Ord [1.19] scene is as much about the new as it is the central climax, when all the vocal parts join 6 A Spotless Rose Philip Ledger [2.00] in homophony, for the first and only time, 7 The Seven Joys of Mary William Whitehead [4.45] old at this time of year; Christmas presents 8 Dormi Jesu John Rutter [4.56] a golden opportunity to present brand new to describe the angels’ voices. 9 Creator of the Stars of Night Plainsong, arr. John Scott [3.41] music to wide audiences, and the role played 0 I Wonder as I Wander Carl Rutti [1.46] by St John’s College Choir in this area has Henry Walford Davies’ popular 1913 q O Little Town of Bethlehem Henry Walford Davies [4.49] been significant, as demonstrated by this arrangement of The Holly and the Ivy sticks w I Saw Three Ships Traditional arr.