Improvised Exploration Through the Realms of Shamanic Chaos Magick, Insight Meditation and Gender Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Sonic Retro-Futures: Musical Nostalgia as Revolution in Post-1960s American Literature, Film and Technoculture Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/65f2825x Author Young, Mark Thomas Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Sonic Retro-Futures: Musical Nostalgia as Revolution in Post-1960s American Literature, Film and Technoculture A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Mark Thomas Young June 2015 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Sherryl Vint, Chairperson Dr. Steven Gould Axelrod Dr. Tom Lutz Copyright by Mark Thomas Young 2015 The Dissertation of Mark Thomas Young is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As there are many midwives to an “individual” success, I’d like to thank the various mentors, colleagues, organizations, friends, and family members who have supported me through the stages of conception, drafting, revision, and completion of this project. Perhaps the most important influences on my early thinking about this topic came from Paweł Frelik and Larry McCaffery, with whom I shared a rousing desert hike in the foothills of Borrego Springs. After an evening of food, drink, and lively exchange, I had the long-overdue epiphany to channel my training in musical performance more directly into my academic pursuits. The early support, friendship, and collegiality of these two had a tremendously positive effect on the arc of my scholarship; knowing they believed in the project helped me pencil its first sketchy contours—and ultimately see it through to the end. -

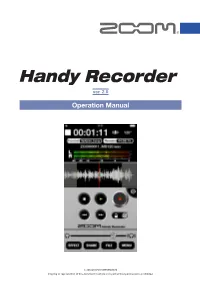

Zoom Handy Recorder App Operations Manual (13 MB Pdf)

ver. 2.0 Operation Manual © 2014 ZOOM CORPORATION Copying or reproduction of this document in whole or in part without permission is prohibited. Contents Introduction‥ ‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 3 Copyrights‥ ‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 3 Main Screen ‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 4 Landscape mode (new in ver. 2.0)‥ ‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 5 Recording‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 6 Pausing recording‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 6 Adjusting the recording level‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 7 Setting the recording format‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 7 Muting the input‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 8 Adding recordings (landscape mode only) (new in ver. 2.0)‥ ‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 9 Using mid-side recording ( series MS mic only feature)‥ ‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 11 Setting mid-side monitoring‥ ‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 11 Playback‥ ‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 12 Selecting‥and‥playing‥files‥ ‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 12 Pausing playback‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 13 Playing‥files‥from‥the‥FILE‥screen‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 13 Adjusting the playback level‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 14 Repeating playback of an interval (new in ver. 2.0) ‥ ‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 14 Editing‥and‥deleting‥files‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 15 Dividing‥files‥(landscape‥mode‥only)‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ -

Ordo Templi Orientis, U.S.A

AGAPÉ VOL. XIX NO. 3/4 The official organ of the U.S. Grand Lodge of O.T.O. A in a in b AnnoB in Viiie VolumeVolume XIX, XVII, No. No. 3/4, 1, 2017 2020 EV EV M M M Ordo Templi Orientis, U.S.A. Mysteria Mystica Maxima E.G.C. 2020 EV 1 A IN a • VVI AGAPÉ VOL. XIX NO. 3/4 FROM THE EDITOR Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law. Welcome to our double-issue of Agapé. We decided to play a little bit of catch-up with this issue, so we can get ourselves back on track and on time. The official organ of the U.S. Grand Lodge of O.T.O. The recent pandemic has affected all of us here, as we’re sure it has you as well. For the time being, we will be CONTENTS publishing issues of Agapé in digital-format only. We’re From the Editor 2 also working on building a new website for Agapé, and From the Grand Master 3 we hope we can show that off to you soon. Updates from the Electoral College 4 Poems by Jori-Ville Rahkonen 5, 13 In the meantime, we hope you’re staying safe and sane Featured Articles 6 U.S.G.L. Officers Directory 14 in these weird times. Please check in on your Siblings, attend the myriad of virtual events local bodies continue to put together, and be well! Love is the law, love under will. Executive Editor: Sabazius X° Editor: Andrew Lent Andrew Assistant Editor: Courtney Padrutt Editor, Agapé Layout: Ron Labhart Proofreading: David Rodgers, Lori Lent Editorial Address: 20436 Route 19, Suite 620 Cranberry Twp, PA 16066 [email protected] Cover Art: Frater Arretos Agapé is published quarterly by Ordo Templi Orientis, U.S.A., a California not-for-profit religious corporation with business offices at P.O. -

Partyman by Title

Partyman by Title #1 Crush (SCK) (Musical) Sound Of Music - Garbage - (Musical) Sound Of Music (SF) (I Called Her) Tennessee (PH) (Parody) Unknown (Doo Wop) - Tim Dugger - That Thing (UKN) 007 (Shanty Town) (MRE) Alan Jackson (Who Says) You - Can't Have It All (CB) Desmond Decker & The Aces - Blue Oyster Cult (Don't Fear) The - '03 Bonnie & Clyde (MM) Reaper (DK) Jay-Z & Beyonce - Bon Jovi (You Want To) Make A - '03 Bonnie And Clyde (THM) Memory (THM) Jay-Z Ft. Beyonce Knowles - Bryan Adams (Everything I Do) I - 1 2 3 (TZ) Do It For You (SCK) (Spanish) El Simbolo - Carpenters (They Long To Be) - 1 Thing (THM) Close To You (DK) Amerie - Celine Dion (If There Was) Any - Other Way (SCK) 1, 2 Step (SCK) Cher (This Is) A Song For The - Ciara & Missy Elliott - Lonely (THM) 1, 2, 3, 4 (I Love You) (CB) Clarence 'Frogman' Henry (I - Plain White T's - Don't Know Why) But I Do (MM) 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New (SF) Cutting Crew (I Just) Died In - Coolio - Your Arms (SCK) 1,000 Faces (CB) Dierks Bentley -I Hold On (Ask) - Randy Montana - Dolly Parton- Together You And I - (CB) 1+1 (CB) Elvis Presley (Now & Then) - Beyonce' - There's A Fool Such As I (SF) 10 Days Late (SCK) Elvis Presley (You're So Square) - Third Eye Blind - Baby I Don't Care (SCK) 100 Kilos De Barro (TZ) Gloriana (Kissed You) Good - (Spanish) Enrique Guzman - Night (PH) 100 Years (THM) Human League (Keep Feeling) - Five For Fighting - Fascination (SCK) 100% Pure Love (NT) Johnny Cash (Ghost) Riders In - The Sky (SCK) Crystal Waters - K.D. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Artist Title DiscID 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night 00321,15543 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants 10942 10,000 Maniacs Like The Weather 05969 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 06024 10cc Donna 03724 10cc Dreadlock Holiday 03126 10cc I'm Mandy Fly Me 03613 10cc I'm Not In Love 11450,14336 10cc Rubber Bullets 03529 10cc Things We Do For Love, The 14501 112 Dance With Me 09860 112 Peaches & Cream 09796 112 Right Here For You 05387 112 & Ludacris Hot & Wet 05373 112 & Super Cat Na Na Na 05357 12 Stones Far Away 12529 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About Belief) 04207 2 Brothers On 4th Come Take My Hand 02283 2 Evisa Oh La La La 03958 2 Pac Dear Mama 11040 2 Pac & Eminem One Day At A Time 05393 2 Pac & Eric Will Do For Love 01942 2 Unlimited No Limits 02287,03057 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 04201 3 Colours Red Beautiful Day 04126 3 Doors Down Be Like That 06336,09674,14734 3 Doors Down Duck & Run 09625 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 02103,07341,08699,14118,17278 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 05609,05779 3 Doors Down Loser 07769,09572 3 Doors Down Road I'm On, The 10448 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 06477,10130,15151 3 Of Hearts Arizona Rain 07992 311 All Mixed Up 14627 311 Amber 05175,09884 311 Beyond The Grey Sky 05267 311 Creatures (For A While) 05243 311 First Straw 05493 311 I'll Be Here A While 09712 311 Love Song 12824 311 You Wouldn't Believe 09684 38 Special If I'd Been The One 01399 38 Special Second Chance 16644 3LW I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) 05043 3LW No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) 09798 3LW Playas Gon' Play -

Джоð½ Зоñ€Ð½ ÐлÐ

Джон Зорн ÐÐ »Ð±ÑƒÐ¼ ÑÐ ¿Ð¸ÑÑ ŠÐº (Ð ´Ð¸ÑÐ ºÐ¾Ð³Ñ€Ð°Ñ„иÑÑ ‚а & график) The Big Gundown https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-big-gundown-849633/songs Spy vs Spy https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/spy-vs-spy-249882/songs Buck Jam Tonic https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/buck-jam-tonic-2927453/songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/six-litanies-for-heliogabalus- Six Litanies for Heliogabalus 3485596/songs Late Works https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/late-works-3218450/songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/templars%3A-in-sacred-blood- Templars: In Sacred Blood 3493947/songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/moonchild%3A-songs-without-words- Moonchild: Songs Without Words 3323574/songs The Crucible https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-crucible-966286/songs Ipsissimus https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/ipsissimus-3154239/songs The Concealed https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-concealed-1825565/songs Spillane https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/spillane-847460/songs Mount Analogue https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/mount-analogue-3326006/songs Locus Solus https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/locus-solus-3257777/songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/at-the-gates-of-paradise- At the Gates of Paradise 2868730/songs Ganryu Island https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/ganryu-island-3095196/songs The Mysteries https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-mysteries-15077054/songs A Vision in Blakelight -

Acknowledgments P. Xi Encountering the Scarlet Goddess P. 1 Western Esotericism, Occultism, and Magic P

Acknowledgments p. xi Encountering the Scarlet Goddess p. 1 Western Esotericism, Occultism, and Magic p. 6 Notes on Methodology p. 8 Technicalities and Demarcations p. 10 Outline of the Book p. 12 Divine Women, Femmes, and Whores: The Theorization of Multiple Femininities p. 17 Feminism and Sex: Passion, Prostitution, and Pleasure p. 18 Difference, Divinity, and Multiple Femininities p. 19 Fem(me)ininity and Vulnerable Subversion p. 23 "The Sex That Is Not One": The Concept of Plural Femininities p. 26 The Scarlet Goddess and the Wine of Her Fornications: Crowley, Babalon, and the Femmep. 35 Fatale 1898-1909 Good, Bad, and Scarlet: Femininities of the Fin-de-Siècle p. 36 Scripture and Scourging: The King James Bible and Pariah Femininities before Babalon p. 39 "Fresh Blossoms from the Heart of Hell": Jezebel and the Influence of Decadence p. 39 "The Work of Wickedness": The Scarlet Woman in Liber AL vel Legis (1904) p. 43 "Into Unguessed Abysses": Lola of the Infernal Bliss p. 46 "I Was Really Being Married": Pain and Erotic Submission in Crowley's Early Work p. 49 The Dancing God and the Pyramid Gateway: Babalon in The Vision and the Voice p. 51 Dancers, Bulls, and Amphoras: Babalon below the Abyss p. 52 Enter the Mother of Abominations: Babalon above the Abyss p. 55 The Daughter and the Blasphemy: Babalon beyond the City of the Pyramids p. 58 Enthroned in Eternity: Babalon in the 2nd Aethyr p. 63 Erotic Destruction and Pariah Femininities: Blood, Receptivity, and Reframed p. 65 Whoredom Yielding Peaches and Women with Whips: Babalon, Crowley, and Magical Systematizationp. -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

Between Liminality and Transgression: Experimental Voice in Avant-Garde Performance

BETWEEN LIMINALITY AND TRANSGRESSION: EXPERIMENTAL VOICE IN AVANT-GARDE PERFORMANCE _________________________________________________________________ A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theatre and Film Studies in the University of Canterbury by Emma Johnston ______________________ University of Canterbury 2014 ii Abstract This thesis explores the notion of ‘experimental voice’ in avant-garde performance, in the way it transgresses conventional forms of vocal expression as a means of both extending and enhancing the expressive capabilities of the voice, and reframing the social and political contexts in which these voices are heard. I examine these avant-garde voices in relation to three different liminal contexts in which the voice plays a central role: in ritual vocal expressions, such as Greek lament and Māori karanga, where the voice forms a bridge between the living and the dead; in electroacoustic music and film, where the voice is dissociated from its source body and can be heard to resound somewhere between human and machine; and from a psychoanalytic perspective, where the voice may bring to consciousness the repressed fears and desires of the unconscious. The liminal phase of ritual performance is a time of inherent possibility, where the usual social structures are inverted or subverted, but the liminal is ultimately temporary and conservative. Victor Turner suggests the concept of the ‘liminoid’ as a more transgressive alternative to the liminal, allowing for permanent and lasting social change. It may be in the liminoid realm of avant-garde performance that voices can be reimagined inside the frame of performance, as a means of exploring new forms of expression in life. -

Circus Arts at O.Z.O.R.A

THE DAILY NEWSPAPER OF THE OZORIAN TRIBE FREE * 4 PAGES SUNDAY AUGUST, 2012 ozorafestival.eu spiced with some dark humor in vaudeville style. The spectacu- lar juggling, acrobatic, trapeze and burlesque dance performers Circus Arts at O.Z.O.R.A. are the s-cream of the international underground circus life.The characters of the performance keep their masks on even after AT THIS YEAR’S FESTIVAL THE their show, mingling with the MODERN CIRCUS ARTS GOT A SPE- audience and further building CIAL SPACE. INTERNATIONALLY the atmosphere, so anything FAMOUS AND PROFESSIONAL CIR- can happen anywhere at any CUS AND JUGGLING GROUPS ARE time! PERFORMING AT THE OPENING CEREMONY AND ON DIFFERENT A new stage at the festival is the STAGES OF THE FESTIVAL. Firespace, this is a project from Germany essentially an open space for fire dancers and fire On the main stage legendary fire jugglers, supports a diversity of artists, like Magma Fire Theather, fire arts. Moreover, we regard Flame Flowers, Firebirds, Freak Fu- Fire Space as a cultural space, sion Cabaret, Anamintas Fire The- allowing for inspiration and in- ather, Mietar, Spark Firedance, Los teraction seeks the best condi- Del Fuego and Firesthetic are pre- tions for audience and artists, senting their new and special proj- as well as for environment and ects. It is also an important mission material. The space is open for us to teach the flow arts. We from dusk till dawn, come by hold and held workshops, where with your fire gear and spin people can try out all kinds of body with us or just sit down around manipulation, circus, juggling and the circle and enjoy the show! acrobatic arts with experienced trainers and safe equipments. -

Olena Semenyaka, the “First Lady” of Ukrainian Nationalism

Olena Semenyaka, The “First Lady” of Ukrainian Nationalism Adrien Nonjon Illiberalism Studies Program Working Papers, September 2020 For years, Ukrainian nationalist movements such as Svoboda or Pravyi Sektor were promoting an introverted, state-centered nationalism inherited from the early 1930s’ Ukrainian Nationalist Organization (Orhanizatsiia Ukrayins'kykh Natsionalistiv) and largely dominated by Western Ukrainian and Galician nationalist worldviews. The EuroMaidan revolution, Crimea’s annexation by Russia, and the war in Donbas changed the paradigm of Ukrainian nationalism, giving birth to the Azov movement. The Azov National Corps (Natsional’nyj korpus), led by Andriy Biletsky, was created on October 16, 2014, on the basis of the Azov regiment, now integrated into the Ukrainian National Guard. The Azov National Corps is now a nationalist party claiming around 10,000 members and deployed in Ukrainian society through various initiatives, such as patriotic training camps for children (Azovets) and militia groups (Natsional’ny druzhiny). Azov can be described as a neo- nationalism, in tune with current European far-right transformations: it refuses to be locked into old- fashioned myths obsessed with a colonial relationship to Russia, and it sees itself as outward-looking in that its intellectual framework goes beyond Ukraine’s territory, deliberately engaging pan- European strategies. Olena Semenyaka (b. 1987) is the female figurehead of the Azov movement: she has been the international secretary of the National Corps since 2018 (and de facto leader since the party’s very foundation in 2016) while leading the publishing house and metapolitical club Plomin (Flame). Gaining in visibility as the Azov regiment transformed into a multifaceted movement, Semenyaka has become a major nationalist theorist in Ukraine. -

Karaoke Book

10 YEARS 3 DOORS DOWN 3OH!3 Beautiful Be Like That Follow Me Down (Duet w. Neon Hitch) Wasteland Behind Those Eyes My First Kiss (Solo w. Ke$ha) 10,000 MANIACS Better Life StarStrukk (Solo & Duet w. Katy Perry) Because The Night Citizen Soldier 3RD STRIKE Candy Everybody Wants Dangerous Game No Light These Are Days Duck & Run Redemption Trouble Me Every Time You Go 3RD TYME OUT 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL Going Down In Flames Raining In LA Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 3T 10CC Here Without You Anything Donna It's Not My Time Tease Me Dreadlock Holiday Kryptonite Why (w. Michael Jackson) I'm Mandy Fly Me Landing In London (w. Bob Seger) 4 NON BLONDES I'm Not In Love Let Me Be Myself What's Up Rubber Bullets Let Me Go What's Up (Acoustative) Things We Do For Love Life Of My Own 4 PM Wall Street Shuffle Live For Today Sukiyaki 110 DEGREES IN THE SHADE Loser 4 RUNNER Is It Really Me Road I'm On Cain's Blood 112 Smack Ripples Come See Me So I Need You That Was Him Cupid Ticket To Heaven 42ND STREET Dance With Me Train 42nd Street 4HIM It's Over Now When I'm Gone Basics Of Life Only You (w. Puff Daddy, Ma$e, Notorious When You're Young B.I.G.) 3 OF HEARTS For Future Generations Peaches & Cream Arizona Rain Measure Of A Man U Already Know Love Is Enough Sacred Hideaway 12 GAUGE 30 SECONDS TO MARS Where There Is Faith Dunkie Butt Closer To The Edge Who You Are 12 STONES Kill 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER Crash Rescue Me Amnesia Far Away 311 Don't Stop Way I Feel All Mixed Up Easier 1910 FRUITGUM CO.