Chief Shavehead

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REVEREND ISAAC Mccoy & the CAREY MISSION

BERRIEN & CASS COUNTY, MICHIGAN PROFILES PRESERVING LOCAL HISTORY WITH PEOPLE, EVENTS & PLACES By Jeannie Watson REVEREND ISAAC McCOY & THE CAREY MISSION Isaac McCoy founded and ran the Carey Mission in Niles, Michigan from 1822-1832. He was a Baptist missionary and minister who served the Native American Indians. His impact on Berrien and Cass County Patawatomi Indians and pioneers was profound having both positive and negative effects. Carey Mission was the "point from which the American frontier was extended." Before Isaac McCoy arrived, Southwest Michigan was considered a savage, dangerous wilderness. He gave the Indians compassion, education and sanctuary, where fear, hatred and war had preceded. In doing so, he built a reputation that provided pioneers the confidence to move into the area. His Carey Mission became a sanctuary for all races, a way station for travelers, and a meeting place for government officials. His methods brought understanding, peace, and co-existence, until serious problems developed. Isaac played a major role in the Indian Removal Act, and was a significant figure in the complex history of Berrien and Cass County. In 1922, the "Fort St. Joseph Chapter of the Daughters Of The American Revolution" located the site of the Carey Mission. It was located one mile west of the St. Joseph River, on what is now Niles-Buchanan Road. Carey Mission consisted of 200 acres of land in 1832, which now encompasses subdivisions, woodlands. The DAR had a large boulder placed at the corner of Niles-Buchaan Road and Philip Street, then attached a plaque, which marked the location of the main entrance to the Carey Mission. -

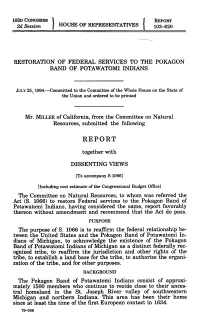

REPORT 2D Session HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES 103-620

103D CONGRESS I REPORT 2d Session HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 103-620 RESTORATION OF FEDERAL SERVICES TO THE POKAGON BAND OF POTAWATOMI INDIANS JULY 25, 1994.-Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed Mr. MILLER of California, from the Committee on Natural Resources, submitted the following REPORT together with DISSENTING VIEWS [To accompany S.1066] [Including cost estimate of the Congressional Budget Office] The Committee on Natural Resources, to whom was referred the Act (S. 1066) to restore Federal services to the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians, having considered the same, report favorably thereon without amendment and recommend that the Act do pass. PURPOSE The purpose of S. 1066 is to reaffirm the federal relationship be- tween the United States and the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi In- dians of Michigan, to acknowledge the existence of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians of Michigan as a distinct federally rec- ognized tribe, to reaffirm the jurisdiction and other rights of the tribe, to establish a land base for the tribe, to authorize the organi- zation of the tribe, and for other purposes. BACKGROUND The Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians consist of approxi- mately 1500 members who continue to reside close to their ances- tral homeland in the St. Joseph River valley of southwestern Michigan and northern Indiana. This area has been their home since at least the time of the first European contact in 1634. 79-006 Early treaty relationships The Pokagon Bank of Potawatomi Indians are the descendants of, and political successors to, the Potawatomi bands that were sig- natories to at least eleven treaties negotiated between representa- tives of the United States and Indian tribal governments: the Trea- ty of Greenville (1795), the Treaty of Grouseland (1806), the Treaty of Spring Wells (1815), The Treaty of the Rapids of the Miami of Lake Erie (1817), the Treaty of St. -

THE Removal of the POTA~ATOMI INDIANS: 1820 TO

The removal of the Potawatomi Indians : 1820 to the trail of death Item Type Thesis Authors McCabe, Michael A. Download date 03/10/2021 01:51:11 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10484/5099 THE REMOvAL OF THE POTA~ATOMI INDIANS: - 1820 TO 'rHE TRAIL OF DEATH A Thesis Presented. To The Faculty of the Graduate School Indiana State Teachers College Terre Haute, Indiana In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arta in Social Studies by Michael A. McCabe- August 1960- . " , ", " "" ,. , '.' , " , .,. , .. , ., '" . " , " , . THESIS APPROVAL SHEET The thesis of Michael A. McCabe, Contri- bution of the Graduate Division, Indiana State Teachers College, Series I, Number 805, under the title--THE REMOVAL OF THE POTAWATOMI INDIANS: 1820 TO THE TRAIL OF DEATH is hereby approved as counting toward the completion of the Master's Degree in the amount of 8 quarter hours' credit. Approval of Thesis Committee: ~ ... !iii ,~ppr;o:val of. !is:sociate Dean, ~ of Instruction "~ )t; for Grad'!late, , S,tudies: ~,~L ;~J\.l/~o i ee.w ' (Date) -;.'~ j~': ,~;, oj '"", lx':' 1,,_ :. __ ,' c, , ] .~ <-."J '-- "1-," '-~' . 38211 , I PREF'ACE During the 1830's and 1840's the Potawatomi and Miami Indians were removed from Indiana. Various reasons for these removals have been given by history writers. Some of the reasons usually found include the following: Because of Black Hawk's War the settlers were afraid of the Indians and wanted them removed; in order to build canals and roads the Indians' lands were needed; the removal of the Indians was a natural result of the popu- lation increase in Indiana; the Indians were removed because of trouble which developed between the races; and so on. -

![People of the Three Fires: the Ottawa, Potawatomi, and Ojibway of Michigan.[Workbook and Teacher's Guide]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7487/people-of-the-three-fires-the-ottawa-potawatomi-and-ojibway-of-michigan-workbook-and-teachers-guide-1467487.webp)

People of the Three Fires: the Ottawa, Potawatomi, and Ojibway of Michigan.[Workbook and Teacher's Guide]

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 321 956 RC 017 685 AUTHOR Clifton, James A.; And Other., TITLE People of the Three Fires: The Ottawa, Potawatomi, and Ojibway of Michigan. Workbook and Teacher's Guide . INSTITUTION Grand Rapids Inter-Tribal Council, MI. SPONS AGENCY Department of Commerce, Washington, D.C.; Dyer-Ives Foundation, Grand Rapids, MI.; Michigan Council for the Humanities, East Lansing.; National Endowment for the Humanities (NFAH), Washington, D.C. REPORT NO ISBN-0-9617707-0-8 PUB DATE 86 NOTE 225p.; Some photographs may not reproduce ;4011. AVAILABLE FROMMichigan Indian Press, 45 Lexington N. W., Grand Rapids, MI 49504. PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Guides - Classroom Use - Guides '.For Teachers) (052) -- Guides - Classroom Use- Materials (For Learner) (051) EDRS PRICE MFU1 /PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *American Indian Culture; *American Indian History; American Indians; *American Indian Studies; Environmental Influences; Federal Indian Relationship; Political Influences; Secondary Education; *Sociix- Change; Sociocultural Patterns; Socioeconomic Influences IDENTIFIERS Chippewa (Tribe); *Michigan; Ojibway (Tribe); Ottawa (Tribe); Potawatomi (Tribe) ABSTRACT This book accompanied by a student workbook and teacher's guide, was written to help secondary school students to explore the history, culture, and dynamics of Michigan's indigenous peoples, the American Indians. Three chapters on the Ottawa, Potawatomi, and Ojibway (or Chippewa) peoples follow an introduction on the prehistoric roots of Michigan Indians. Each chapter reflects the integration -

A Ten-Year Plan to End Homelessness 2006-2016

Cass County A Ten-Year Plan To End Homelessness 2006-2016 Cover and document photo credits to Kristina Barroso-Burrell and the Cass County website. Our vision… By 2016, everyone in Cass County will be enabled to live in a safe and decent home. To obtain a copy of this plan or for more information, please contact: Shelley Klug, Associate Planner Southwest Michigan Planning Commission 185 East Main Street, Suite 701 Benton Harbor, MI 49022 www.swmpc.org [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.......................................................................................... 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY........................................................................................... 6 AN OVERVIEW OF CASS COUNTY ....................................................................... 9 Population................................................................................................................ 12 Housing.................................................................................................................... 16 Health and Human Services ................................................................................... 22 HOMELESSNESS IN CASS COUNTY ................................................................... 23 Issues........................................................................................................................ 24 Solutions................................................................................................................... 37 Summary ................................................................................................................. -

Simon Pokagon: Charlatan Or Authentic Spokesman for the 19Th-Century Anishinaabeg?

Simon Pokagon: Charlatan or Authentic Spokesman for the 19th-century Anishinaabeg? LAWRENCE T. MARTIII University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire There are a number of fairly early accounts of Anishmaabe oral traditions found in writings of European and Euro-American missionaries, travelers, and early anthropologists. The best known of these are probably those published by Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, who was Indian Agent in Sault Ste. Marie (Mich.) and Mackinac from 1822 to 1841 (Williams 1991:xix-xx). Fairly recently recognition has been given to the writings of Schoolcraft's mixed-blood wife, Jane Johnston Schoolcraft (Ruoff 1996c). Jane Schoolcraft was one of many 19th-century Anishinaabeg who were raised at least partially in a traditional way, spoke Anishinaabemowin as their first language, but became Christianized and educated in the literate tradition, and then wrote down something of traditional Anishinaabe oral tradition. Other examples are William Warren, George Copway, Peter Jones, and Andrew Blackbird. These writers are, in a sense, the Anishi naabe equivalent of the Beowulf 'poet or the Icelander Snorri Sturluson — people who in a sense had one foot in the Christianized literate tradition and the other in the pre-Christian oral tradition. A quest for native writers with this sort of dual stance led me to spend a month or two at the Newberry Library in Chicago. In the catalog of the Ayer collection, I came upon a reference to a "Potawatomie Book of Genesis". Something about the catalog entry suggested that this was not simply a translation of the biblical book of Genesis into Potawatomi, and I put in a request for the book. -

The Emigrant Métis of Kansas: Rethinking the Pioneer Narrative Written by Shirley E

THE EMIGRANT MÉTIS OF KANSAS: RETHINKING THE PIONEER NARRATIVE by SHIRLEY E. KASPER B.A., Marshall University, 1971 M.S., University of Kansas, 1984 M.A., University of Missouri-Kansas City, 1998 A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History 2012 This dissertation entitled: The Emigrant Métis of Kansas: Rethinking the Pioneer Narrative written by Shirley E. Kasper has been approved for the Department of History _______________________________________ Dr. Ralph Mann _______________________________________ Dr. Virginia DeJohn Anderson Date: April 13, 2012 The final copy of this dissertation has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. iii ABSTRACT Kasper, Shirley E. (Ph.D., History) The Emigrant Métis of Kansas: Rethinking the Pioneer Narrative Dissertation directed by Associate Professor Ralph Mann Under the U.S. government’s nineteenth century Indian removal policies, more than ten thousand Eastern Indians, mostly Algonquians from the Great Lakes region, relocated in the 1830s and 1840s beyond the western border of Missouri to what today is the state of Kansas. With them went a number of mixed-race people – the métis, who were born of the fur trade and the interracial unions that it spawned. This dissertation focuses on métis among one emigrant group, the Potawatomi, who removed to a reservation in Kansas that sat directly in the path of the great overland migration to Oregon and California. -

Chief Simon Pokagon : “The Indian Longfellow”

Chief Simon Pokagon : “The Indian Longfellow” David H. Dickason* Pokagon is now an almost forgotten name except among those travelers in the Midwest who visit the Potawatomi Inn in Indiana’s Pokagon State Park or the small village of Pokagon in Cass County, Michigan. But during his lifetime Chief Simon Pokagon of the Potawatomi’ was known to many because of his two visits with Lincoln at the White House, his appearance as unassuming guest of honor and orator for the Chicago Day celebrations at the Columbian Exposition, his various other public addresses, and his articles on Indian subjects in national magazines.2 His most extensive literary work, the prose-poetry romance of the forest entitled O-Gi- Maw-Kwe Mit-I-ma-Ki (Queen of the Woods), was in type but not yet published at the time of his death in 1899. His contemporary reputation was such that the editor of the Review of R<eviews referred to “this distinguished Pottawattomie chieftain” as “one of the most remarkable men of our time. His great eloquence, his sagacity, and his wide range of information mark him as a man of excep- tional endowments.”a A feature article in the Arena spoke of “this noble representative of the red-man” as “simple-hearted and earnest.”‘ Looked on as the “best educated full-blood Indian of his time,”5 he was called the “ ‘Longfellow of his * David H. Dickason is professor of English at Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana. 1 For a biographical study of his father, Chief Leopold, with brief notes on Simon, see Cecelia Bain Buechner, The Pokagons (Indiana Historical Society Publications, Vol. -

Isaac Mccoy : His Plan of and Work for Indian Colonization

Fort Hays State University FHSU Scholars Repository Master's Theses Graduate School Spring 1939 Isaac McCoy : His Plan of and Work For Indian Colonization. Emory J. Lyons Fort Hays Kansas State College Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.fhsu.edu/theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Lyons, Emory J., "Isaac McCoy : His Plan of and Work For Indian Colonization." (1939). Master's Theses. 300. https://scholars.fhsu.edu/theses/300 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at FHSU Scholars Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of FHSU Scholars Repository. ISAA C MCCOY: His Plan of and Work f or Indian Colonization b eing A t h esi s presen ted to t h e Gradu ate Fa culty of t h e Fort Hay s Kan sas State Coll ege i n partial fulfillment of t h e r equ i r ement s f or t h e Degr ee of Mast er of Sc ience by Emory J . _!:y ons, A. B., 193ry Ottawa Uni v ersi t y . Chr . Gradu a t e Coun c i l I 9680 ii 4 £1. P R E F A C E Several books and articles have been written concerning Isaa.c McCoy, but as far ai.s I am able to find out there has been no book, article, or research paper written on the plan of Indian colonization tha.t originated with McCoy, and his work f or the fulfillment of that plan. -

The Indians and the Michigan Road

The Indians and the Michigan Road Juanita Hunter* The United States Confederation Congress adopted on May 20, 1785, an ordinance that established the method by which the fed- eral government would transfer its vast, newly acquired national domain to private ownership. According to the Land Ordinance of 1785 the first step in this transferral process was purchase by the government of all Indian claims. In the state of Indiana by 1821 a series of treaties had cleared Indian title from most land south of the Wabash River. Territory north of the river remained in the hands of the Miami and Potawatomi tribes, who retained posses- sion of at least portions of the area until their removals from the state during the late 1830s and early 1840s.’ After a brief hiatus following 1821, attempts to secure addi- tional cessions of land from the Indians in Indiana resumed in 1826. In the fall of that year three commissioners of the United States government-General John Tipton, Indian agent at Fort Wayne; Lewis Cass, governor of Michigan Territory; and James Brown Ray, governor of Indiana-met with leading chiefs and warriors of the Potawatomi and Miami tribes authorized in part “to propose an exchange of land. acre for acre West, of the Mississippi . .’’z The final treaty, signed October 26, 1826, contained no provision for complete Indian removal from the state. The Potawatomis agreed, however, to three important land cessions and received cer- tain benefits that included payment of debts and claims held against * Juanita Hunter is a graduate of Indiana State Teachers College, Terre Haute, and was a social studies teacher at Logansport High School, Logansport, Indiana, at the time of her retirement. -

The Centennial of “The Trail of Death” Irvingmckm on September 4, 1838, the Last Considerable Body of Indians in Indiana Was Forcibly Removed

The Centennial of “The Trail of Death” IRVINGMcKm On September 4, 1838, the last considerable body of Indians in Indiana was forcibly removed. The subsequent emigration of these Indians to the valley of the Osage River in Kansas has been appropriately named “The Trail of Death” by Jacob P. Dunn.l An article by Benjamin F. Stuart deal- ing with the removal of Menominee and his tribe, and Judge William Polke’s journal^' tell a vital part of the story.* In addition there are two monuments at Twin Lakes, Marshall County, that mark the scene of this removal. One is a statue of a conventional Indian upon a lofty pedestal with the following inscription : In Memory of Chief Menominee And His Band of 859 Pottawattomie Indians Removed From This Reservation Sept. 4, 1838 By A Company of Soldiers Under Command of General John Tipton Authon’zed By Governor David Wallace. Immediately below the above historical matter, the fol- lowing 2s inscribed: Governor of Indiana J. Frank Hanly Author of Law Representative Daniel McDonald, Plymouth Trustees Colonel A. F. Fleet, Culver Colonel William Hoynes, Notre Dame Charles T. Mattingly, Plymouth Site Donated By John A. McFarlin 1909 The second memorial is a tableted rock a quarter of a mile away from the first, at the northern end of the larger of the Twin Lakes, which marks the location of an old In- dian chapel. The inscription reads : Site of Menominee Chapel Pottawattomie Indian Church at 1 True Zndian Stories (Indianapolis, 1909). 237. ’ Stuart, “The Deportation of Menominee and His Tribe of Pottawattomie Indians.” Indiana Mawine of History (Septemher, 1922). -

Potawatomi Indians of the West: Origins of the Citizen Band

This dissertation has been 61-3062 microfilmed exactly as received MURPHY, Joseph Francis, 1910— POTAWATOMI INDIANS OF THE WEST: ORIGINS OF THE CITIZEN BAND. The University of Oklahoma, Ph.D., 1961 History, archaeology University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan Copyright by Joseph Francis Murphy 1961 THE UNIVERSITY OF OKIAHOMA. GRADUATE COLLEGE POTAWATOMI INDIANS OF THE WEST ORIGINS OF THE CITIZEN BAND A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY JOSEPH FRANCIS MURPHY Norman, Oklahoma 1961 POTAWATOMI INDIANS OF THE WEST: ORIGINS OF THE CITIZEN BAND APPROVED BY DISSERTATION COMMITTEE ACKNOWLEDGMENT It is with the deepest sense of gratitude that the àüthdr'"âcknowledges the assistance of Dr. Donald J. Berthrong, Department of History, University of Oklahoma, who gave so unsparingly of his time in directing all phases of the prep aration of this dissertation. The other members of the Dissertation Committee, Dr. Gilbert C. Fite, Dr. W. Eugene Hollon, Dr. Arrell M. Gibson, and Dr. Robert E. Bell were also most kind in performing their services during a very busy season of the year. Many praiseworthy persons contributed to the success of the period of research. Deserving of special mention are: Miss Gladys Opal Carr, Library of the University of Oklahoma; Mrs. 0. C. Cook, Mrs. Relia Looney, and Mrs, Dorothy Williams, all of the Oklahoma Historical Society, Oklahoma Çity; Mrs. Lela Barnes and M r . Robert W. Richmond of the Kansas State Historical Society, Topeka; and Father Augustin Wand, S. J., St. Mary's College, St. Marys, Kansas.