Advocacy for the Implementation of the Vested Property Return Act

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Name : Mr. Rajarshi Chakrabarty Designation : Assistant Professor

Name : Mr. Rajarshi Chakrabarty Designation : Assistant Professor Email, Contact Number & Address : [email protected]/[email protected] Research Area/ Ph. D: Urban History Distinction, Awards & Scholarships: Awarded Professor B.B. Chaudhuri Prize for Best Paper in the section on Social & Economic History of India, presented at the 71st session of the Indian History Congress, 2011. Publication: International: 1. Raja Krisnanath:Bangla Renaissance Ekjon Ujjal kintu Abahelita Baktito, published in Itihas Probondha Mala 2010, Itihas Academy, Dhaka, ISSN 1995-1000. 2. Krishnath College er Troi: Masterda Suryasen, Abul Barkat o Anowar Pasha, published in Itihas Probondha Mala 2011, Itihas Academy, Dhaka, ISSN 1995-1000. 3. Desh Bibhager Prekshapote Murshidabad Jela, published in Itihas Samity Patrika, Bangladesh Itihas Samity, ISSN 1560-7585. National Level Publication: 1. Shatranj Ke Khiladi and Umrao Jaan: Revisiting History through Films (received Professor B. B. Chaudhuri Prize), published in the Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, 71st Session, Malda, 2010-11, ISSN 2249-1937. 2. Bharater Jouna Sankhaloghu Andolon er Opor Bishwayaner Probhab, published in Proceedings of the UGC Sponsored National Seminar on “One and a half decade of Globalization”, organized by Barrackpore Rashtraguru Surendranath College and Samaj Bijwan Paricharcha-O-Gabesona Samsad. 3. Emulating Radha for Krsna Bhakti, published in the proceedings of UGC Sponsored National Seminar held at Krishnagar Govt. College titled Panchadas abong Sorosh Sataker Bhakti o Sufi Andolon: tar Aitihasik, Rajnaitik, abong Darshonik Prekshapot Bichar. State Level Publication: 1. Poschimbanga jounata o samajik linga nirman er korana prantik manus der sangathita andolon, published in Itihas Anusandhan 23, Paschimbanga Itihas Samsad. Local Level Publication: 1. -

State Denial, Local Controversies and Everyday Resistance Among the Santal in Bangladesh

The Issue of Identity: State Denial, Local Controversies and Everyday Resistance among the Santal in Bangladesh PhD Dissertation to attain the title of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) Submitted to the Faculty of Philosophische Fakultät I: Sozialwissenschaften und historische Kulturwissenschaften Institut für Ethnologie und Philosophie Seminar für Ethnologie Martin-Luther-University Halle-Wittenberg This thesis presented and defended in public on 21 January 2020 at 13.00 hours By Farhat Jahan February 2020 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Burkhard Schnepel Reviewers: Prof. Dr. Burkhard Schnepel Prof. Dr. Carmen Brandt Assessment Committee: Prof. Dr. Carmen Brandt Prof. Dr. Kirsten Endres Prof. Dr. Rahul Peter Das To my parents Noor Afshan Khatoon and Ghulam Hossain Siddiqui Who transitioned from this earth but taught me to find treasure in the trivial matters of life. Abstract The aim of this thesis is to trace transformations among the Santal of Bangladesh. To scrutinize these transformations, the hegemonic power exercised over the Santal and their struggle to construct a Santal identity are comprehensively examined in this thesis. The research locations were multi-sited and employed qualitative methodology based on fifteen months of ethnographic research in 2014 and 2015 among the Santal, one of the indigenous groups living in the plains of north-west Bangladesh. To speculate over the transitions among the Santal, this thesis investigates the impact of external forces upon them, which includes the epochal events of colonization and decolonization, and profound correlated effects from evangelization or proselytization. The later emergence of the nationalist state of Bangladesh contained a legacy of hegemony allowing the Santal to continue to be dominated. -

Islami Bank Bangladesh Limited Corporate Investment Wing Sustainable Finance Division Corporate Social Responsibility Department Head Office, Dhaka

Islami Bank Bangladesh Limited Corporate Investment Wing Sustainable Finance Division Corporate Social Responsibility Department Head Office, Dhaka. Sub: Result of IBBL Scholarship Program, HSC Level-2019 Following 1500(Male-754, Female-746) students mentioned below have been selected finally for IBBL Scholarship program, HSC Level -2019. Sl. No. Name of Branch Beneficiary ID Student's Name Father's Name Mother's Name 1 Agrabad Branch 8880202516103 Halimatus Sadia Didarul Alam Jesmin Akter 2 Agrabad Branch 8880202516305 Imam Hossain Mahbubul Hoque Aleya Begum 3 Agrabad Branch 8880202508003 Md Mahmudul Hasan Al Qafi Mohammad Mujibur Rahman Shaheda Akter 4 Agrabad Branch 8880202516204 Proma Mallik Gopal Mallik Archana Mallik 5 Alamdanga Branch 8880202313016 Mst. Husniara Rupa Md. Habibur Rahman Mst. Nilufa Yeasmin 6 Alamdanga Branch 8880202338307 Sharmin Jahan Shormi Md. Abdul Khaleque Israt Jahan 7 Alanga SME/Krishi Branch 8880202386310 Tammim Khan Mim Md. Gofur Khan Mst. Hamida Khanom 8 Amberkhana Branch 8880202314017 Fahmida Akter Nitu Babul Islam Najma Begum 9 Amberkhana Branch 8880202402015 Fatema Akter Abdul Kadir Peyara Begum 10 Amberkhana Branch 8880202252201 Mahbubur Rahman Md. Juned Ahmed Mst. Shomurta Begum 11 Amberkhana Branch 8880202208505 Md. Al-Amin Moin Uddin Rafia Begum 12 Amberkhana Branch 8880202457814 Md. Ismail Hossen Md. Rasedul Jaman Ismotara Begum 13 Amberkhana Branch 8880202413118 Mst. Shima Akter Tofazzul Islam Nazma Begum 14 Amberkhana Branch 8880202378513 Tania Akther Muffajal Hossen Kamrun Nahar 15 Amberkhana Branch 8880202300618 Tanim Islam Tanni Shahidul Islam Shibli Islam 16 Amberkhana Branch 8880202234504 Tanjir Hasan Abdul Malik Rahena Begum 17 Anderkilla Branch 8880202497414 Arpita Barua Alak Barua Tapasi Barua 18 Anderkilla Branch 8880202269108 Sakibur Rahman Mohammad Younus Ruby Akther 19 Anwara Branch 8880202320115 Jinat Arabi Mohammad Fajlul Azim Raihan Akter 20 Anwara Branch 8880202263607 Mizanur Rahman Abdul Khalaque Monwara Begum 21 Anwara Branch 8880202181101 Mohammad Arif Uddin Mohammad Shofi Fatema Begum Sl. -

Hindus in South Asia & the Diaspora: a Survey of Human Rights 2007

Hindus in South Asia and the Diaspora: A Survey of Human Rights 2007 www.HAFsite.org May 19, 2008 “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights” (Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948, Article 1) “Religious persecution may shield itself under the guise of a mistaken and over-zealous piety” (Edmund Burke, February 17, 1788) Endorsements of the Hindu American Foundation's 3rd Annual Report “Hindus in South Asia and the Diaspora: A Survey of Human Rights 2006” I would like to commend the Hindu American Foundation for publishing this critical report, which demonstrates how much work must be done in combating human rights violations against Hindus worldwide. By bringing these abuses into the light of day, the Hindu American Foundation is leading the fight for international policies that promote tolerance and understanding of Hindu beliefs and bring an end to religious persecution. Senator Sherrod Brown (D-OH) Freedom of religion and expression are two of the most fundamental human rights. As the founder and former co-chair of the Congressional Caucus on India, I commend the important work that the Hindu American Foundation does to help end the campaign of violence against Hindus in South Asia. The 2006 human rights report of the Hindu American Foundation is a valuable resource that helps to raise global awareness of these abuses while also identifying the key areas that need our attention. Congressman Frank Pallone, Jr. (D-NJ) Several years ago in testimony to Congress regarding Religious Freedom in Saudi Arabia, I called for adding Hindus, Sikhs and Buddhists to oppressed religious groups who are banned from practicing their religious and cultural rights in Saudi Arabia. -

Chapter-I Historical Background: a Reflection

Chapter-I Historical Background: A Reflection 1 Chapter-I Historical Background: A Reflection The „Refugee and Migration Problem‟ is not a new phenomenon on the pages of History. However, it is difficult to determine when and how the movement of the refugees and the process of migration started. It is believed that History witnessed its first „Refugee and Migration Problem‟ with the Exodus that took place in c1446 B.C. under the leadership of Mosses.1 In case of Bengal, the „Refugee and Migration Problem‟ was largely the product of its Partition in 1947. However, it may reasonably be assumed that after the Pakistan Resolution of 1940, migration of the upper caste Hindus commenced from the eastern part of Bengal. The process got accelerated in 1946 when a horrible riot took place in Noakhali and other such areas in East Bengal. But with the Partition of British India and therewith also of Bengal in 1947 the influx of refugees into West Bengal began in large scale. However, before going into details let us have a short look at the key factors which played vital roles behind the Partition of India vis-à-vis Bengal in 1947. It may be said that the process of the Partition of Indian provinces started in 712 A.D. when Mohammad Ibn-al Qasim, popularly known as Mohammad Bin Kasim, Son-in-law of the Governor of Iraq, al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf al-Thaqafi, defeated Dahir, the Brahmin King of Sind, in the battle of „Raor‟ and captured it. Though, the impact of the Arabs rule in Sind did not last long, unquestionably, it sowed the seed of Islam on Indian soil.2 Some of the local people embraced Islam on their own accord and some of the upper caste Hindu rulers might have accepted the same in order to retain their existing political status. -

Beacon 2018 College Building

BEACON 2018 COLLEGE BUILDING BEACON 2018 A PICTORIAL YEAR BOOK NATIONAL DEFENCE COLLEGE MIRPUR CANTONMENT, DHAKA, BANGLADESH Contents Editorial Board 07 Commandant’s Message 09 Governing Body 10 Family Album 11 Course Opening 47 Guest Speakers 51 Internal Visits 81 Miscellaneous Activities 107 Social and Cultural Activities 120 Overseas Study Tour 132 Graduation Dinner 148 Graduation Ceremony 152 Editorial Board Lt Gen Sheikh Mamun Khaled SUP, rcds, psc, PhD Chief Patron Col Shahriar Zaman, afwc, psc, G Lt Col A S M Badiul Alam, afwc, psc, G+, Arty Editor Associate Editor Maj Lasker Jewel Rana, psc, Inf Lt Cdr Israth Zahan, (ND), BN Asst Dir Md. Nazrul Islam Assistant Editor Assistant Editor Assistant Editor BEACON 2018 │ 7 Commandant’s Message 8 │ BEACON 2018 I am extremely delighted to see the 18th issue of Pictorial Yearbook of NDC “BEACON”, which has quite vividly portrayed the glimpses of courses curricula and activities conducted in the National Defence College (NDC). I am sanguine that the Course Members, the faculty, staff and the alumni alike would love to scan down this pictorial book to stroll through the nostalgic and colourful memory lane. All concerned will find this magazine as a treasure trove of happy memories. NDC is the premier national institution in Bangladesh, a centre of excellence conducting training, research and education on defence, security, strategy and development studies. With the passage of time this prestigious institution has developed into an important training institution for the selected senior military and civil services officers from home and abroad on national and international security related matters as well as to impart training to mid-ranking military officers of Bangladesh Armed Forces on war studies. -

Political Political Economy of Fundamentalism of Fundamentalism in Bangladesh

Political Economy of Fundamentalism in Bangladesh Abul Barkat Professor, Department of Economics, University of Dhaka, Dhaka, Bangladesh (email: [email protected]; [email protected]) March 06, 2013 Political Economy of Fundamentalism in Bangladesh: Abul Barkat 2 Political Economy of Fundamentalism in Bangladesh: Abul Barkat 3 Abstract: The genesis of Islam reveals liberal and humanistic origin of Islam in East Bengal. But this liberal -humanistic Islam has turned in to “Political Islam” mainly due to three major regressive transformations associated with the emergence of “religious doctrine-based Pakistan State” (in 1947), failure in punishing the ‘war criminals’ (in 1971 War of Independence), and legitimizing communalism by replacing `secularism’ by “Islam as state religion” in the Constitution (eighth amendment 1988). The failure of the State in satisfying basic needs of the people, growing criminalization of economy and politics, growing inequality in society, increasing youth unemployment, communalization of culture and education, lack of people’s confidence on mainstream political (democratic) leadership, external environment – all contributed to the growth of Islamist extremism in Bangladesh. Religious fundamentalism, in the process, has gained momentum to shape organized `political Islam’, which intends to capture the state power by force. The religious fundamentalist forces have successfully assimilated the mythos of religion with logos of reality, and pursuing their aim of capturing the state power by using religion as pretext through an well organized economic power based political process. In so doing, the fundamentalists have created “an economy within the economy“, and “a state within the state”. They have adequate economic strength (from micro to macro levels) to sustain their political organizations. -

Why Do I Speak Bangla?

dhakat ribune.co m http://www.dhakatribune.com/op-ed/2014/feb/19/why-do-i-speak-bangla Why do I speak Bangla? Behnaz Ahmed I have a love-hate relationship with dinner parties. As a Bengali twentysomething who grew up in the United States, you could say these gatherings def ined a certain part of my cultural upbringing. In suburban American-Bengali communities, these af f airs usually involve women, “aunties” as I call them, crowding around a kitchen, assisting the host serve culinary marvels straight f rom Siddika Kabir’s cookbook. Their husbands sit in the drawing room and attempt to solve the world’s political problems over a game of cards. Late into the evening, there is tea, and if we’re lucky, the culturally enlightened among us will f ind a harmonium somewhere and grace us with their talents. What’s there not to like? So we’ve talked about the love, let’s talk about some of the hate. While I was growing up, it was without f ail that at these gatherings, I was asked in some way or f orm: “Your Bangla’s pretty good, how did you learn to speak so well?” I never really understood why my linguistic capabilities earned me so much Bengali party street cred. One thing the nine-year-old me did know was if I f orgot Bangla, the next winter vacation I went to Dhaka, my Mama, one of my f avourite people in the world, probably wouldn’t buy me an ice cream cone if I asked f or it in English. -

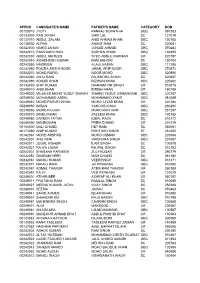

Appno Candidate's Name Father's Name Category Dob

APPNO CANDIDATE'S NAME FATHER'S NAME CATEGORY DOB 00120010 JYOTI PANKAJ TEWATHIA OBC 091283 00133030 RAN SINGH SHIV LAL SC 121079 00137010 ABDUL SALAM ANIS AHMAD KHAN OBC 150785 00138030 ALPNA ANANT RAM SC 220681 00242000 NAHID JAHAN JUNAID AHMAD OBC 070482 00242010 RAMZAAN KHAN SUBHAN KHAN OBC 160885 00242030 ABDUL MATEEN SYED ABDUL RAHMAN UR 020787 00242040 AWADHESH KUMAR RAM BAHORI SC 130784 00242050 NAZREEN ALAULHASAN OBC 111185 00242060 FOUZIA ARSHI NOOR JAMAL ARIF NOOR OBC 270872 00242070 MOHD RAFIQ NOOR MOHD OBC 020980 00242080 ANJU RANI RAJENDRA SINGH SC 020887 00242090 KOSAR KHAN RIZWAN KHAN OBC 220682 00143020 SHIV KUMAR DHARAM VIR SINGH UR 010878 00249010 ANIS KHAN IDRISH KHAN UR 190789 00249020 MUJAHID MOHD YUSUF SHAIKH SHAIKH YUSUF USMANGANI OBC 220787 00249030 MOHAMMAD ADEEL MOHAMMAD ZAKIR OBC 081089 00249040 MOHD PARVEJ KHAN MOHD ILIYAS KHAN UR 020184 00249050 IMRAN YAKOOB KHAN OBC 230284 00249060 MOHD RIJUAN MOHD RAFI ARIF OBC 251287 00249070 BINDU KHAN SALEEM KHAN OBC 160785 00249080 ZAHEEN FATMA IQBAL RAZA SC 010172 00249090 MANMOHAN PREM CHAND UR 201279 00166000 DULI CHAND HET RAM SC 030681 00173080 ANIP KUMAR ROHTASH SINGH ST 231085 00142061 MOHD ARSHAD MOHD USMAN OBC 220686 00242001 ANU RANI VIRENDRA SINGH OBC 201087 00242011 JUGAL KISHOR ILAM SINGH SC 100578 00242021 RAJYA LAXMI RAJPAL SINGH SC 010783 00242031 SHABANA PARVEEN ZULFAQQAR UR 290779 00242051 DHARAM VEER MAM CHAND SC 061180 00242061 MANOJ KUMAR VEERSINGH OBC 010171 00242071 MANJU RANI JAI PRAKASH OBC 010585 00242081 KOMAL THAKUR ATMA RAM THAKUR UR 260388 -

Mapping Bangladesh's Political Crisis

Mapping Bangladesh’s Political Crisis Asia Report N°264 | 9 February 2015 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Anatomy of a Conflict ....................................................................................................... 3 A. A Bitter History .......................................................................................................... 3 B. Democracy Returns ................................................................................................... 5 C. The Caretaker Model Ends ........................................................................................ 5 D. The 2014 Election ...................................................................................................... 6 III. Political Dysfunction ........................................................................................................ 8 A. Parliamentary Incapacity ........................................................................................... 8 B. An Opposition in Disarray ......................................................................................... 9 1. BNP Politics ......................................................................................................... -

ANINDITA BANDYOPADHYAY [email protected] Mobile No--+91 9434306797,+91 8697349079

ANINDITA BANDYOPADHYAY [email protected] mobile no--+91 9434306797,+91 8697349079 Professor Department of Bengali University of Burdwan Burdwan-713104 West Bengal,India Date of Birth: 20.04.1962 Academic Qualification: - MA, Department of Bengali, Vidya Bhavana, Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan - 1985 - PhD, Department of Bengali, Vidya Bhavana,Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan - 2002 Teaching Experience: - Professor, Department of Bengali, University of Burdwan, 2012 – present - Associate Professor, Department of Bengali, University of Burdwan, 2006 - 2012 - Reader, Department of Bengali, University of Burdwan, 2002 - 2005 - Lecturer, Bolpur College, University of Burdwan, 1993 - 2002 Professional Experience: - Head of Department, Department of Bengali, University of Burdwan, 2009 – 2011 - Coordinator, Bengali Course, Directorate of Distance Education, University of Burdwan,2009--2011 - Joint Coordinator of 3 Refresher Courses, Academic Staff College, University of Burdwan - Coordinator of NET-SET,Dept.of Bengali,University of Burdwan 2014 Published Books: Five (05) Published Essays: Thirty eight( 39),including 04 in international journals and book Delivered lectures: Fifty six (56) including 08 international ones Present Projects: a) Cultural history of Bengal: contribution of "Surabhi o Pataka" in collaboration with National Council of Education, Jadavpur University,K olkata b) Child marriage: in Bengali Society and Literature (1847-1929)--personal project c) Rabindranath: as reflected in Nineteenth century periodicals, in collaboration with Bangiya Sahitya Parishad (funded by West Bengal Govt Ph.D. awarded under my supervision: 09 Running Doctoral Fellow: 03 M.Phil. awarded under my supervision: 10 Doing M.Phil. Dissertation: 01 Papers presented in conferences, seminars, workshop, symposia No. Title of the lecture Thrust Area Organiser / Place International/ Date national/state level 1. -

BANGLADESH – Joint Civil Society Report

BANGLADESH – Joint Civil Society Report BANGLADESH Civil Society Report on the Implementation of the ICCPR (Replies to the List of Issues CCPR/C/BGD/Q/1) For the Review of the Initial State Report of Bangladesh (CCPR/C/BGD/1) At the 119th session of the Human Rights Committee (Geneva – March 2017) Submitted by: Coalition of individual Human Rights Defenders Bangladesh 6 February 2017 With the support of : Centre for Civil and Political Rights 1 BANGLADESH – Joint Civil Society Report Table of Contents I. Introduction 3 II. Civil Society Replies to LOI 4 a. Non-discrimination and equality between men and women (arts. 2, 3 and 26) 4 b. Right to life (art. 6) 6 c. Prohibition of torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment; liberty and security of person, treatment of persons deprived of their liberty (arts. 7, 9 and 10) 8 d. Elimination of slavery and servitude (art. 8) 9 e. Freedom of religion, opinion and eXpression, and freedom of association (arts. 18, 19 and 22) 10 f. Rights of the child (art. 24) 17 g. Right to participate in public life and vote in free and fair elections (art. 25) 18 h. Right of minorities and indigenous peoples, freedom of movement, right to privacy and home (arts. 27, 12 and 17) 18 2 BANGLADESH – Joint Civil Society Report I. Introduction This report is prepared finalised by a group of individual human rights defenders and practitioners who have contributed both in organizational and individual capacity, with support of the Centre for Civil and Political Rights. A workshop was held on 28 January 2017 in Dhaka, Bangladesh, to elaborate and finalise the present report.