Flowering Records of Some Subalpine Trees and Shrubs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEWSLETTER NUMBER 84 JUNE 2006 New Zealand Botanical Society

NEW ZEALAND BOTANICAL SOCIETY NEWSLETTER NUMBER 84 JUNE 2006 New Zealand Botanical Society President: Anthony Wright Secretary/Treasurer: Ewen Cameron Committee: Bruce Clarkson, Colin Webb, Carol West Address: c/- Canterbury Museum Rolleston Avenue CHRISTCHURCH 8001 Subscriptions The 2006 ordinary and institutional subscriptions are $25 (reduced to $18 if paid by the due date on the subscription invoice). The 2006 student subscription, available to full-time students, is $9 (reduced to $7 if paid by the due date on the subscription invoice). Back issues of the Newsletter are available at $2.50 each from Number 1 (August 1985) to Number 46 (December 1996), $3.00 each from Number 47 (March 1997) to Number 50 (December 1997), and $3.75 each from Number 51 (March 1998) onwards. Since 1986 the Newsletter has appeared quarterly in March, June, September and December. New subscriptions are always welcome and these, together with back issue orders, should be sent to the Secretary/Treasurer (address above). Subscriptions are due by 28th February each year for that calendar year. Existing subscribers are sent an invoice with the December Newsletter for the next years subscription which offers a reduction if this is paid by the due date. If you are in arrears with your subscription a reminder notice comes attached to each issue of the Newsletter. Deadline for next issue The deadline for the September 2006 issue is 25 August 2006 Please post contributions to: Joy Talbot 17 Ford Road Christchurch 8002 Send email contributions to [email protected] or [email protected]. Files are preferably in MS Word (Word XP or earlier) or saved as RTF or ASCII. -

Council Member Guest Editorial

E-newsletter: No 107. October 2010 Deadline for next issue: Wednesday 14 November 2012 Council member guest editorial In 2005, I remember giving a presentation to my fellow reference librarians at Christchurch City Libraries on a range of electronic resources providing information about New Zealand’s environment. The Network’s website particularly impressed me and it wasn’t long before I signed up as a member. Back then, I never would have predicted that I would have the opportunity to contribute to that impressive website, but here I am doing just that! As many of you will have read in the August issue of Trilepidea, the Network’s website is undergoing some redevelopment to improve usability. I am enjoying the challenge of helping to improve access to the amazing trove of information contained on our website. I’ve rediscovered hidden corners of the website I’d forgotten about and great new additions such as the lichens and macroalgae species pages. The amazing range of images contributed by hundreds of photographers is a powerful resource that will feature more prominently in the redeveloped site. The new site will be launched soon and I am looking forward to hearing what people think about the changes. Keep your ears and eyes open for the new website and please send your feedback to: [email protected]. There will also be some exciting changes to the Favourite Native Plant vote this year. Though some people may find this annual exercise a bit frivolous, I think it provides a good excuse to share our love for native plants with everyone. -

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT (Ff AGRICULTURE

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT (ff AGRICULTURE INVENTORY No. Washington, D. C. T Issued February, 1930 PLANT MATERIAL INTRODUCED BY THE OFFICE OF FOREIGN PLANT INTRODUCTION, BUREAU OF PLANT INDUSTRY, JULY 1 TO SEPTEMBER 30,1928 (NOS. 77261 TO 77595) CONTENTS Page Introductory statement 1 Inventory 3 Index of common and scientific names 19 INTRODUCTORY STATEMENT The most outstanding plant material contained in this inventory, No. 96, covering the period from July 1 to September 30, 1928, is the collection of 51 sugarcane varieties (Saccarum offvoinarum, Nos. 77334 to 77384) procured by E. W. Brandes in New Guinea for use in his official investigations. Part of the interest in this shipment is due to the fact that Doctor Brandes is the first agricultural explorer to use an airplane for his collecting tour. Doctor Brandes not only collected sugarcanes in person but also obtained the cooper- ation of P. H. Goldfinch, Sydney, Australia, who sent in a collection of 44 varieties (Nos. 77496 to 77539). Another lot of five varieties (Nos. 77298 to 77302) was received from Argentina. As in the previous inventory, the bulk of the plant material received in this period comes from the Southern Hemisphere. Through the activities of Mrs. Frieda Cobb Blanchard two collections of Australian plants (Nos. 77273 to 77292 and Nos. 77441 to 77447), as well as a collection from New Zealand (Nos. 77540 to 77582), were received. Through O. F. Cook there was received a collection of rubber-producing plants (Nos. 77387 to 77394) from Haiti. Five kinds of cover crops (Nos. 77293 to 77297) from Ceylon may be of value for the southern United States. -

Patterns of Flammability Across the Vascular Plant Phylogeny, with Special Emphasis on the Genus Dracophyllum

Lincoln University Digital Thesis Copyright Statement The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). This thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: you will use the copy only for the purposes of research or private study you will recognise the author's right to be identified as the author of the thesis and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate you will obtain the author's permission before publishing any material from the thesis. Patterns of flammability across the vascular plant phylogeny, with special emphasis on the genus Dracophyllum A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of philosophy at Lincoln University by Xinglei Cui Lincoln University 2020 Abstract of a thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of philosophy. Abstract Patterns of flammability across the vascular plant phylogeny, with special emphasis on the genus Dracophyllum by Xinglei Cui Fire has been part of the environment for the entire history of terrestrial plants and is a common disturbance agent in many ecosystems across the world. Fire has a significant role in influencing the structure, pattern and function of many ecosystems. Plant flammability, which is the ability of a plant to burn and sustain a flame, is an important driver of fire in terrestrial ecosystems and thus has a fundamental role in ecosystem dynamics and species evolution. However, the factors that have influenced the evolution of flammability remain unclear. -

An Assessment for Fisheries Operating in South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands

FAO International Plan of Action-Seabirds: An assessment for fisheries operating in South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands by Nigel Varty, Ben Sullivan and Andy Black BirdLife International Global Seabird Programme Cover photo – Fishery Patrol Vessel (FPV) Pharos SG in Cumberland Bay, South Georgia This document should be cited as: Varty, N., Sullivan, B. J. and Black, A. D. (2008). FAO International Plan of Action-Seabirds: An assessment for fisheries operating in South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands. BirdLife International Global Seabird Programme. Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, The Lodge, Sandy, Bedfordshire, UK. 2 Executive Summary As a result of international concern over the cause and level of seabird mortality in longline fisheries, the United Nations Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO) Committee of Fisheries (COFI) developed an International Plan of Action-Seabirds. The IPOA-Seabirds stipulates that countries with longline fisheries (conducted by their own or foreign vessels) or a fleet that fishes elsewhere should carry out an assessment of these fisheries to determine if a bycatch problem exists and, if so, to determine its extent and nature. If a problem is identified, countries should adopt a National Plan of Action – Seabirds for reducing the incidental catch of seabirds in their fisheries. South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands (SGSSI) are a United Kingdom Overseas Territory and the combined area covered by the Territorial Sea and Maritime Zone of South Georgia is referred to as the South Georgia Maritime Zone (SGMZ) and fisheries within the SGMZ are managed by the Government of South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands (GSGSSI) within the framework of the Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living (CCAMLR). -

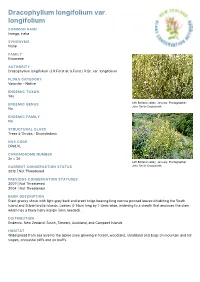

Dracophyllum Longifolium Var. Longifolium

Dracophyllum longifolium var. longifolium COMMON NAME Inanga, inaka SYNONYMS None FAMILY Ericaceae AUTHORITY Dracophyllum longifolium (J.R.Forst et G.Forst.) R.Br. var. longifolium FLORA CATEGORY Vascular – Native ENDEMIC TAXON Yes ENDEMIC GENUS Left Borland valley, January. Photographer: John Smith-Dodsworth No ENDEMIC FAMILY No STRUCTURAL CLASS Trees & Shrubs - Dicotyledons NVS CODE DRALVL CHROMOSOME NUMBER 2n = 26 Left Borland valley, January. Photographer: CURRENT CONSERVATION STATUS John Smith-Dodsworth 2012 | Not Threatened PREVIOUS CONSERVATION STATUSES 2009 | Not Threatened 2004 | Not Threatened BRIEF DESCRIPTION Erect grassy shrub with light grey bark and erect twigs bearing long narrow pointed leaves inhabiting the South Island and Subantarctic Islands. Leaves 4-14cm long by 1-4mm wide, widening to a sheath that encloses the stem which has a finely hairy margin (lens needed). DISTRIBUTION Endemic. New Zealand: South, Stewart, Auckland, and Campbell Islands HABITAT Widespread from sea level to the alpine zone growing in forest, woodland, shrubland and bogs on mountain and hill slopes, oncoastal cliffs and on bluffs. FEATURES Erect to spreading single–stemmed shrub or tree 1–12 m tall. Bark on old branches grey to blackish brown, finely to deeply fissured, young stems reddish brown. Leaves dimorphic. Juvenile leaves spirally arranged or crowded at tips of branches, erect to spreading; lamina sheath 9–20 × 5–11 mm, light green, shoulders tapering to truncate and margin ciliate in upper half; lamina 100.0–250.0 × 2.5–7.0 mm, linear–triangular to lanceolate; margins serrulate with 50–80 teeth per 10 mm. Adult leaves erect to spreading; lamina sheath 5–15 × 4–7 mm, light green, striate, shoulders rounded to auricled and margin membranous with the top half ciliate; lamina 40–232 × 1–6 mm, linear to linear–triangular, prominently striated; margins serrulate with 120–170 teeth per 10 mm; apex triquetrous. -

Notification of Access Arrangement for MP 41279, Mt Te Kuha

Attachment C Draft Terrestrial Ecology Report 106 VEGETATION AND FAUNA OF THE PROPOSED TE KUHA MINE SITE Prepared for Te Kuha Limited Partnership October 2013 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Te Kuha mining permit is located predominantly within the Westport Water Conservation Reserve (1,825 ha), which is a local purpose reserve administered by the Buller District Council. The coal deposit is situated outside the water catchment within an area of approximately 490 ha of Brunner Coal Measures vegetation approximately 5 km southwest of Mt Rochfort. Access would be required across conservation land to reach the coal resource. The Te Kuha site was recommended as an area for protection by the Protected Natural Areas Programme surveys in the 1990s on the basis that in the event it was removed from the local purpose reserve for any reason, addition to the public conservation estate would increase the level of protection of coal measures habitats which, although found elsewhere (principally in the Mt Rochfort Conservation Area), were considered inadequately protected overall. The proposal to create an access road and an opencast mine at the site would affect twelve different vegetation types to varying degrees. The habitats present at the proposed mine site are overwhelmingly indigenous and have a very high degree of intactness reflecting their lack of human disturbance. Previous surveys have shown that some trees in the area are more than 500 years old. Habitats affected by the proposed access road are less intact and include exotic pasture as well as regenerating shrubland and forest. Te Kuha is not part of the Department of Conservation’s Buller Coal Plateaux priority site and is unlikely to receive management for that reason. -

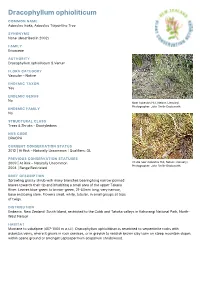

Dracophyllum Ophioliticum

Dracophyllum ophioliticum COMMON NAME Asbestos Inaka, Asbestos Turpentine Tree SYNONYMS None (described in 2002) FAMILY Ericaceae AUTHORITY Dracophyllum ophioliticum S.Venter FLORA CATEGORY Vascular – Native ENDEMIC TAXON Yes ENDEMIC GENUS No Near Asbestos Hut, Nelson (January). Photographer: John Smith-Dodsworth ENDEMIC FAMILY No STRUCTURAL CLASS Trees & Shrubs - Dicotyledons NVS CODE DRAOPH CURRENT CONSERVATION STATUS 2012 | At Risk – Naturally Uncommon | Qualifiers: OL PREVIOUS CONSERVATION STATUSES 2009 | At Risk – Naturally Uncommon At site near Asbestos Hut, Nelson (January). Photographer: John Smith-Dodsworth 2004 | Range Restricted BRIEF DESCRIPTION Sprawling grassy shrub with many branches bearing long narrow pointed leaves towards their tip and inhabiting a small area of the upper Takaka River. Leaves blue-green to brown-green, 21-50mm long, very narrow, base enclosing stem. Flowers small, white, tubular, in small groups at tops of twigs. DISTRIBUTION Endemic. New Zealand: South Island, restricted to the Cobb and Takaka valleys in Kahurangi National Park, North- West Nelson. HABITAT Montane to subalpine (457-1000 m a.s.l.). Dracophyllum ophioliticum is restricted to serpentinite rocks with asbestos veins, where it grows in rock crevices, or in greyish to reddish brown clay loam on steep mountain slopes within opens ground or amongst Leptospermum scoparium shrub/wood. FEATURES Shrub 0.3m-1.0 m tall but reaching 2.0 m in shade, multi-stemmed, decumbent; bark grey and finely fissured. Leaves spreading and crowded at the tips of branches, sheathing at base; sheath glaucous to light green, 4-9 mm x4-8 mm, coriaceous, striate, shoulder rounded to truncate, margin ciliate; lamina coriaceous, glaucous to light green, linear-triangular, 2-50 x 1.0-2.5 mm, slightly concave, surfaces minutely verrucose and covered in short, white scabrid caducous hairs; margin serrulate, with 10-13 teeth per cm; apex triquetrous. -

1992 New Zealand Botanical Society President: Dr Eric Godley Secretary/Treasurer: Anthony Wright

NEW ZEALAND BOTANICAL SOCIETY NEWSLETTER NUMBER 28 JUNE 1992 New Zealand Botanical Society President: Dr Eric Godley Secretary/Treasurer: Anthony Wright Committee: Sarah Beadel, Ewen Cameron, Colin Webb, Carol West Address: New Zealand Botanical Society C/- Auckland Institute & Museum Private Bag 92018 AUCKLAND Subscriptions The 1992 ordinary and institutional subs are $14 (reduced to $10 if paid by the due date on the subscription invoice). The 1992 student sub, available to full-time students, is $7 (reduced to $5 if paid by the due date on the subscription invoice). Back issues of the Newsletter are available at $2.50 each - from Number 1 (August 1985) to Number 28 (June 1992). Since 1986 the Newsletter has appeared quarterly in March, June, September and December. New subscriptions are always welcome and these, together with back issue orders, should be sent to the Secretary/Treasurer (address above). Subscriptions are due by 28 February of each year for that calendar year. Existing subscribers are sent an invoice with the December Newsletter for the next year's subscription which offers a reduction if this is paid by the due date. If you are in arrears with your subscription a reminder notice comes attached to each issue of the Newsletter. Deadline for next issue The deadline for the September 1992 issue (Number 29) is 28 August 1992. Please forward contributions to: Ewen Cameron, Editor NZ Botanical Society Newsletter C/- Auckland Institute & Museum Private Bag 92018 AUCKLAND Cover illustration Mawhai (Sicyos australis) in the Cucurbitaceae. Drawn by Joanna Liddiard from a fresh vegetative specimen from Mangere, Auckland; flowering material from Cuvier Island herbarium specimen (AK 153760) and the close-up of the spine from West Island, Three Kings Islands herbarium specimen (AK 162592). -

Interactive Effects of Climate Change and Species Composition on Alpine Biodiversity and Ecosystem Dynamics

Interactive effects of climate change and plant invasion on alpine biodiversity and ecosystem dynamics Justyna Giejsztowt M.Sc., 2013 University of Poitiers, France; Christian-Albrechts University, Germany B. Sc., 2010 University of Canterbury, New Zealand A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Biological Sciences Victoria University of Wellington Te Herenga Waka 2019 i ii This thesis was conducted under the supervision of Dr Julie R. Deslippe (primary supervisor) Victoria University of Wellington Wellington, New Zealand And Dr Aimée T. Classen (secondary supervisor) University of Vermont Burlington, United States of America iii iv “May your mountains rise into and above the clouds.” -Edward Abbey v vi Abstract Drivers of global change have direct impacts on the structure of communities and functioning of ecosystems, and interactions between drivers may buffer or exacerbate these direct effects. Interactions among drivers can lead to complex non-linear outcomes for ecosystems, communities and species, but are infrequently quantified. Through a combination of experimental, observational and modelling approaches, I address critical gaps in our understanding of the interactive effects of climate change and plant invasion, using Tongariro National Park (TNP; New Zealand) as a model. TNP is an alpine ecosystem of cultural significance which hosts a unique flora with high rates of endemism. TNP is invaded by the perennial shrub Calluna vulgaris (L.) Hull. My objectives were to: 1) determine whether species- specific phenological shifts have the potential to alter the reproductive capacity of native plants in landscapes affected by invasion; 2) determine whether the effect of invasion intensity on the Species Area Relationship (SAR) of native alpine plant species is influenced by environmental stress; 3) develop a novel modelling framework that would account for density-dependent competitive interactions between native species and C. -

Dracophyllum Urvilleanum

Dracophyllum urvilleanum COMMON NAME D’urvilles Grass Tree SYNONYMS None FAMILY Ericaceae AUTHORITY Dracophyllum urvilleanum A.Rich. FLORA CATEGORY Vascular – Native ENDEMIC TAXON No ENDEMIC GENUS Dracophyllum urvilleanum. Photographer: No Shannel Courtney ENDEMIC FAMILY No STRUCTURAL CLASS Trees & Shrubs - Dicotyledons NVS CODE DRAURV CURRENT CONSERVATION STATUS 2012 | At Risk – Naturally Uncommon | Qualifiers: PD Dracophyllum urvilleanum. Photographer: Shannel Courtney PREVIOUS CONSERVATION STATUSES 2009 | At Risk – Naturally Uncommon | Qualifiers: DP 2004 | Threatened – Nationally Vulnerable BRIEF DESCRIPTION Erect grassy shrub with many very long and fine grass-like wavy leaves inhabiting the northern tip of the South Island. Leaves 54-128mm long by 0.4-1.7mm wide, abruptly narrowing to a lobed base that sheaths the stem. Flowers white, in clusters of 2-4 on short side branches, nearly hidden by leaves. DISTRIBUTION Endemic. northern South Island where it is known from Abel Tasman National Park eastwards to the Marlborough Sounds. HABITAT Coastal. Growing on cliff faces and in coastal scrub and forest often within the splash zone. FEATURES Small single–stemmed shrub or small tree 2–8 m tall. Bark on old branches grey to greyish brown, finely fissured, young stems reddish brown. Leaves dimorphic. Juvenile leaves spirally arranged along branches, spreading to recurved; lamina sheath 5.0–6.0 × 1.3–1.5 mm, truncate, yellowish green, margin membranous with the upper half ciliate; lamina 79.0–145.0 × 1.5–3.7 mm, linear–triangular, margins serrulate with 40–50 teeth per 10 mm. Adult leaves spreading to recurved; lamina sheath 3.6–9.0 × 2.5–3.0 mm, thinly coriaceous, shoulders truncate to auricled and margins membranous with the top half ciliate; lamina 33.0–128.0 × 0.42–1.68 mm, linear to linear–triangular, adaxial surface sometimes shortly scabrid; margins serrulate with 45–60 teeth per 10 mm. -

NOTES on AGATHIS AUSTRALIS. by C

NOTES ON AGATHIS AUSTRALIS. By C. T. SANDO. Introduction.—Much has been published about our kauri (Agathis australis) and it is now generally recognised as one of the finest coniferous trees of the world. The New Zealand species is one of a genus of ten—the most important being— A. Palmerstoni ... (Queensland) A. microstachya ... (Queensland) A. robusta ... (Queensland and Philippine Islands) A. vitiensis * ... (Fiji) A. alba ... (Malaya, Sumatra, Java, Celebes, Borneo, and Philippine Islands) A. lanceolata ... (New Caledonia) A. macrophylla ... (Solomon Islands) The value of Agathis australis was first recognised before 1800 by which time a considerable trade in kauri spars had sprung up between Australia and New Zealand. Later, naval-store ships were sent out from England for cargoes and from that time on kauri has increased in value. Up till a short time ago it was used for building and interior furnishing, but now the limited supplies demand a price far too high for these purposes so that its present uses have been confined to carriage building, cabinet-making, and general joinery, vats, tubs, and other special purposes. Wanton waste has so depleted out kauri areas that now, more than ever it is forced upon us, the necessity of making very serious attempts at conservation of the remaining supplies and propagation of this tree for scenic purposes, and, if economic conditions warrant it, for timber production. Geographical, Climatic, and Edaphic Range.—Kauri occurs in the northern parts of the North Island except in the extreme northern peninsula. It is found from Ahipara and Mangonui in the north as far south as the Bay of Plenty on the East Coast and Kawhia Harbour on the west, i.e.