The Gordon Gekko Effect

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CIVIL SERVICES EXAMINATION Section

u RAU’S IAS—UPSC Syllabus for Civil Services Exam u CIVIL SERVICES EXAMINATION Section - I Plan of Exam The Civil Services Examination comprises two successive stages : (i) Civil Services (Preliminary) Examinations (Objective Type) for the selection of candidates for Main Examination; and (ii) Civil Services (Main) Examination (Written and Interview) for the selection of candidates for the various services and posts. The Preliminary Examination will consist of two papers of Objective type (multiple choice questions) and carry a maximum of 450 marks [ General Studies - 150 marks and any one optional subject (out of 23 subjects) – 300 marks] in the subjects mentioned in Section II. There are four alternatives for the answer to every question. For each question for which a wrong answer has been given by the candidate, one- third (0.33) of the marks assigned to that question will be deducted as penalty. This examination is meant to serve as a screening test only; the marks obtained in the Preliminary Examination by the candidates who are declared qualified for admission to the Main Examination will not be counted for determining their final order of merit. The number of candidates to be admitted to the Main Examination will be about twelve to thirteen times the total approximate number of vacancies to be filled in the year in the various Services and Posts. Only those candidates who are declared by the Commission to have qualified in the Preliminary Examination in a year will be eligible for admission to the Main Examination of that year provided they are otherwise eligible for admission to the Main Examination. -

Buddhism in America

Buddhism in America The Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series The United States is the birthplace of religious pluralism, and the spiritual landscape of contemporary America is as varied and complex as that of any country in the world. The books in this new series, written by leading scholars for students and general readers alike, fall into two categories: some of these well-crafted, thought-provoking portraits of the country’s major religious groups describe and explain particular religious practices and rituals, beliefs, and major challenges facing a given community today. Others explore current themes and topics in American religion that cut across denominational lines. The texts are supplemented with care- fully selected photographs and artwork, annotated bibliographies, con- cise profiles of important individuals, and chronologies of major events. — Roman Catholicism in America Islam in America . B UDDHISM in America Richard Hughes Seager C C Publishers Since New York Chichester, West Sussex Copyright © Columbia University Press All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Seager, Richard Hughes. Buddhism in America / Richard Hughes Seager. p. cm. — (Columbia contemporary American religion series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN ‒‒‒ — ISBN ‒‒‒ (pbk.) . Buddhism—United States. I. Title. II. Series. BQ.S .'—dc – Casebound editions of Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. -

Broadcasting Taste: a History of Film Talk, International Criticism, and English-Canadian Media a Thesis in the Department of Co

Broadcasting Taste: A History of Film Talk, International Criticism, and English-Canadian Media A Thesis In the Department of Communication Studies Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication Studies) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada December 2016 © Zoë Constantinides, 2016 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Zoë Constantinides Entitled: Broadcasting Taste: A History of Film Talk, International Criticism, and English- Canadian Media and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in Communication Studies complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: __________________________________________ Beverly Best Chair __________________________________________ Peter Urquhart External Examiner __________________________________________ Haidee Wasson External to Program __________________________________________ Monika Kin Gagnon Examiner __________________________________________ William Buxton Examiner __________________________________________ Charles R. Acland Thesis Supervisor Approved by __________________________________________ Yasmin Jiwani Graduate Program Director __________________________________________ André Roy Dean of Faculty Abstract Broadcasting Taste: A History of Film Talk, International Criticism, and English- Canadian Media Zoë Constantinides, -

Faculty Development Programme on Entrepreneurship & Innovation 1

1 Faculty Development Programme on Entrepreneurship & Innovation Faculty Development Programme in Entrepreneurship & Innovation December 21-31, 2016 at Sarvajanik College of Engineering & Technology Supported by National Science & Technology Entrepreneurship Development Board Department of Science & Technology, Government of India (NSTEDB) UNDER DST-NIMAT PROJECT Sardar Vallabhbhai National Institute of Technology Jointly Organizes with Sarvajanik College of Engineering & Technology Rationale Among several initiatives taken at various levels against the backdrop that entrepreneurship can be taught like any other discipline, the recent and a notable one is the establishment of the Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship (MSDE), by the Union Government of India. The efforts will not just develop entrepreneurial and employability skills among the youth but will also deliver world class Learning and Management System (LMS) to equip potential as well as early stage entrepreneurs. Besides, Government's pan India programmes, viz. 'Startup India', 'Stand-up India', 'Make-in India', 'Digital India', 'Swachha Bharat (Clean India)', aim at further propelling entrepreneurship movement in India. Sculpting its mandate around the mission of nationwide promotion of entrepreneurship, EDC aids the efforts by training faculty members to impart learning in entrepreneurship as well as counsel youths to adopt this discipline as a career. In SCET, Entrepreneur Development Cell aims to "create entrepreneurial culture in SCET to foster growth of innovation and entrepreneurship amongst the students". Since inception in September 2014 under the guidance of Dr. Vaishali Mungurwadi, EDC has organized 19 motivational introductory lectures, 12 guest lectures, 03 industrial visits, 03 workshops and two Entrepreneurship Awareness camp and one Institute visit to motivate the students. -

The Not-So-Spectacular Now by Gabriel Broshy

cinemann The State of the Industry Issue Cinemann Vol. IX, Issue 1 Fall/Winter 2013-2014 Letter from the Editor From the ashes a fire shall be woken, A light from the shadows shall spring; Renewed shall be blade that was broken, The crownless again shall be king. - Recited by Arwen in Peter Jackson’s adaption of the final installment ofThe Lord of the Rings Trilogy, The Return of the King, as her father prepares to reforge the shards of Narsil for Ara- gorn This year, we have a completely new board and fantastic ideas related to the worlds of cinema and television. Our focus this issue is on the states of the industries, highlighting who gets the money you pay at your local theater, the positive and negative aspects of illegal streaming, this past summer’s blockbuster flops, NBC’s recent changes to its Thursday night lineup, and many more relevant issues you may not know about as much you think you do. Of course, we also have our previews, such as American Horror Story’s third season, and our reviews, à la Break- ing Bad’s finale. So if you’re interested in the movie industry or just want to know ifGravity deserves all the fuss everyone’s been having about it, jump in! See you at the theaters, Josh Arnon Editor-in-Chief Editor-in-Chief Senior Content Editor Design Editors Faculty Advisor Josh Arnon Danny Ehrlich Allison Chang Dr. Deborah Kassel Anne Rosenblatt Junior Content Editor Kenneth Shinozuka 2 Table of Contents Features The Conundrum that is Ben Affleck Page 4 Maddie Bender How Real is Reality TV? Page 6 Chase Kauder Launching -

Beyond the Pink: (Post) Youth Iconography in Cinema

Beyond the Pink: (Post) Youth Iconography in Cinema Christina Lee Bachelor of Arts with First Class Honours in Communication Studies This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Murdoch University 2005 Declaration I declare that this dissertation is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. ______________________ Christina LEE Hsiao Ping i Publications and Conference Presentations Refereed Publications Christina Lee. “Party people in the house(s): The hobos of history” in Liverpool of the South Seas: Perth and Its Popular Music. Tara Brabazon (ed.) Crawley: University of Western Australia Press, 2005. pp. 43-52. This chapter was written in association with the research on rave culture, as featured in Chapter Six. Christina Lee. “Let me entertain you” in TTS Australia: Critical Reader. Bec Dean (ed.) Northbridge: PICA, 2005. pp. 17-18. This piece was written in association with the research on nationalism and xenophobia, as featured in Chapter Seven. Christina Lee. “Lock and load(up): The action body in The Matrix”, Continuum: Journal of Media and Cultural Studies, forthcoming 2005. This journal article was written in association with the research on simulacra and masculinity, as featured in Chapter Two and Chapter Seven. Conference Presentations “Lock and Load(up): The Action Body in The Matrix”. Alchemies: Community Exchanges. 7th Annual Humanities Graduate Research Conference. Curtin University of Technology: Bentley, Australia. 6-7 November, 2003. This conference presentation was derived from research on the simulacra and the action hardbody as presented in Chapter Two and Chapter Seven. -

Sesiune Speciala Intermediara De Repartitie - August 2018 DACIN SARA Aferenta Difuzarilor Din Perioada 01.04.2008 - 31.03.2009

Sesiune speciala intermediara de repartitie - August 2018 DACIN SARA aferenta difuzarilor din perioada 01.04.2008 - 31.03.2009 TITLU TITLU ORIGINAL AN TARA R1 R2 R3 R4 R5 R6 R7 R8 R9 S1 S2 S3 S4 S5 S6 S7 S8 S9 S10 S11 S12 S13 S14 S15 A1 A2 3:00 a.m. 3 A.M. 2001 US Lee Davis Lee Davis 04:30 04:30 2005 SG Royston Tan Royston Tan Liam Yeo 11:14 11:14 2003 US/CA Greg Marcks Greg Marcks 1941 1941 1979 US Steven Bob Gale Robert Zemeckis (Trecut, prezent, viitor) (Past Present Future) Imperfect Imperfect 2004 GB Roger Thorp Guy de Beaujeu 007: Viitorul e in mainile lui - Roger Bruce Feirstein - 007 si Imperiul zilei de maine Tomorrow Never Dies 1997 GB/US Spottiswoode ALCS 10 produse sau mai putin 10 Items or Less 2006 US Brad Silberling Brad Silberling 10.5 pe scara Richter I - Cutremurul I 10.5 I 2004 US John Lafia Christopher Canaan John Lafia Ronnie Christensen 10.5 pe scara Richter II - Cutremurul II 10.5 II 2004 US John Lafia Christopher Canaan John Lafia Ronnie Christensen 100 milioane i.Hr / Jurassic in L.A. 100 Million BC 2008 US Griff Furst Paul Bales 101 Dalmatians - One Hamilton Luske - Hundred and One Hamilton S. Wolfgang Bill Peet - William 101 dalmatieni Dalmatians 1961 US Clyde Geronimi Luske Reitherman Peed EG/FR/ GB/IR/J Alejandro Claude Marie-Jose 11 povesti pentru 11 P/MX/ Gonzalez Amos Gitai - Lelouch - Danis Tanovic - Alejandro Gonzalez Amos Gitai - Claude Lelouch Danis Tanovic - Sanselme - Paul Laverty - Samira septembrie 11'09''01 - September 11 2002 US Inarritu Mira Nair SACD SACD SACD/ALCS Ken Loach Sean Penn - ALCS -

Administration of Barack Obama, 2012 Remarks to the United Nations

Administration of Barack Obama, 2012 Remarks to the United Nations General Assembly in New York City September 25, 2012 Mr. President, Mr. Secretary-General, fellow delegates, ladies and gentleman: I would like to begin today by telling you about an American named Chris Stevens. Chris was born in a town called Grass Valley, California, the son of a lawyer and a musician. As a young man, Chris joined the Peace Corps and taught English in Morocco. And he came to love and respect the people of North Africa and the Middle East. He would carry that commitment throughout his life. As a diplomat, he worked from Egypt to Syria, from Saudi Arabia to Libya. He was known for walking the streets of the cities where he worked, tasting the local food, meeting as many people as he could, speaking Arabic, listening with a broad smile. Chris went to Benghazi in the early days of the Libyan revolution, arriving on a cargo ship. As America's representative, he helped the Libyan people as they coped with violent conflict, cared for the wounded, and crafted a vision for the future in which the rights of all Libyans would be respected. And after the revolution, he supported the birth of a new democracy, as Libyans held elections and built new institutions and began to move forward after decades of dictatorship. Chris Stevens loved his work. He took pride in the country he served, and he saw dignity in the people that he met. And 2 weeks ago, he traveled to Benghazi to review plans to establish a new cultural center and modernize a hospital. -

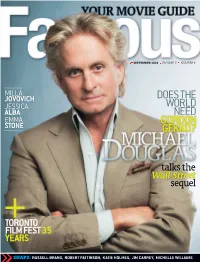

Does the World Need Gordon Gekko?

SEPTEMBER 2010 VOLUME 11 NUMBER 9 MILLA JOVOVICH DOES THE JESSICA WORLD ALBA NEED EMMA GORDON STONE GEKKO? talks the Wall Street sequel + TORONTO FILM FEST 35 YEARS PUBLICATIONS MAIL AGREEMENT NO. 40708019 SNAPS: RUSSELL BRAND, ROBERT PATTINSON, KATIE HOLMES, JIM CARREY, MICHELLE WILLIAMS FORDFO FLEX - With so many comfort features it’s no wonder Flex has so many fans. AAvailable features like heated leather seats, multi-panel Vista Roof™, interior refrigerator anand more. All on optional 20 inch wheels so you can ride in style, no matter where you’re ririding.d It’s a family vehicle for the whole family. Visit ford.ca for more. Starting from $29,999† MSRP Highway: 8.4L/100km (34 MPG)° City: 12.6L/100km (22 MPG)° V ehicle shown with optional equipment. °Estimated fuel consumption for 2011 Ford Flex. Fuel consumption ratings based on Transport Canada approved test methods. Actual fuel consumption may vary based on road conditions, vehicle loading and equipment, and driving habits. † 2011 Flex SE FWD starting from $29,999MSRP (Manufacturer’s Suggested Retail Price). Optional features, freight, Air Tax, licence, fuel fill charge, insurance, PDI, PPSA, administration fees, any environmental charges or fees, and all applicable taxes extra. Dealer may sell or lease for less. Model shown is Limited FWD starting from $41,199 MSRP. InsideFamous SEPTEMBER 2010VOLUME 11•9 regulars EDITOR’S NOTE6 CAUGHT ON FILM8 ENTERTAINMENT IN BRIEF10 SPOTLIGHT12 IN THEATRES14 STYLE42 DVD RELEASES46 TRIVIA48 FAMOUS LAST WORDS50 features DOUBLE TROUBLE20 Jessica Alba plays twins in director Robert Rodriguez’s Machete. And with four movies coming out this year, she says it not the size of the roles that counts, but how you use them • By Jim Slotek cover RUMOUR HAS IT24 story Emma Stone on playing a teen who takes control of the rumour mill in Easy A • By Bob Strauss EVIL DOER30 Milla Jovovich models, sings 34 and twitters, but nothing beats THE MONEY MAN Michael Douglasreturns as “greed is good” guru Gordon Gekko in theWall Street the rush of whacking zombies. -

Afi's 100 Years…100 Heroes and Villains Rank Heroes Villains 1

AFI'S 100 YEARS…100 HEROES AND VILLAINS RANK HEROES VILLAINS 1. Atticus Finch Dr. Hannibal Lecter (in TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD) (in THE SILENCE OF THE LAMBS) 2. Indiana Jones Norman Bates (in RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK) (in PSYCHO) 3. James Bond Darth Vader (in DR. NO) (in THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK) 4. Rick Blaine The Wicked Witch of the West (in CASABLANCA) (in THE WIZARD OF OZ) 5. Will Kane Nurse Ratched (in HIGH NOON) (in ONE FLEW OVER THE CUCKOO’S NEST) 6. Clarice Starling Mr. Potter (in THE SILENCE OF THE LAMBS) (in IT’S A WONDERFUL LIFE) 7. Rocky Balboa Alex Forrest (in ROCKY) (in FATAL ATTRACTION) 8. Ellen Ripley Phyllis Dietrichson (in ALIENS) (in DOUBLE INDEMNITY) 9. George Bailey Regan MacNeil (in IT’S A WONDERFUL LIFE) (in THE EXORCIST) 10. T. E. Lawrence The Queen (in LAWRENCE OF ARABIA) (in SNOW WHITE AND THE SEVEN DWARFS) 11. Jefferson Smith Michael Corleone (in MR. SMITH GOES TO (in THE GODFATHER: PART II) WASHINGTON) 12. Tom Joad Alex De Large (in THE GRAPES OF WRATH) (in CLOCKWORK ORANGE) 13. Oskar Schindler HAL 9000 (in SCHINDLER’S LIST) (in 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY) 14. Han Solo The Alien (in STAR WARS) (in ALIEN) 15. Norma Rae Webster Amon Goeth (in NORMA RAE) (in SCHINDLER’S LIST) 16. Shane Noah Cross (in SHANE) (in CHINATOWN) 17. Harry Callahan Annie Wilkes (in DIRTY HARRY) (in MISERY) 18. Robin Hood The Shark (in THE ADVENTURES OF ROBIN (in JAWS) HOOD) 19. Virgil Tibbs Captain Bligh (in IN THE HEAT OF THE NIGHT) (in MUTINY ON THE BOUNTY) 20. -

Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps

WALL STREET: He’s a ‘green’ version of Gekko’s former protégé Bud Fox (Charlie Sheen) – who also makes a cameo in this MONEY NEVER SLEEPS follow-up. Jake meets his prospective father-in-law, (Cert 15) who expresses a need to be reconciled with his daughter. Reel Issues author: Clive Price Overview: Sequel to Oliver Stone’s Wall Street of Gekko shows Jake how to take revenge on merciless 1987, this latest incarnation shows fallen money guru finance executive Bretton James (Josh Brolin), who was Gordon Gekko ending his eight-year prison sentence behind the downfall of Jake’s mentor Lou Zabel (Frank for insider trading. It appears he wants to make peace Langella). However, as always, there is much more to with friends and family, but in reality he’s planning a Gekko than meets the eye. Eventually it emerges he’s return to the stock markets – with a vengeance. really after a fund belonging to his daughter. Producer and director: Oliver Stone (2010). Jake persuades Winnie to sign over her money, Length: 127 minutes. Cautions: includes swearing. thinking it could help fund an eco-friendly power scheme. But Gekko makes off with the loot. He THE FILM vanishes, leaving an empty apartment behind. Jake and Winnie split, and it looks like life is over for them. Financial wizard Gordon Gekko – played once again The turning point comes when Jake tracks him down by Michael Douglas – has paid his biggest bill yet. and shows him a video clip of his baby grandson, He’s just completed an eight-year custodial sentence growing in Winnie’s womb. -

Wall Street 1987

WALL STREET ORIGINAL STORY AND SCREENPLAY BY STANLEY WEISER AND OLIVER STONE FIRST DRAFT EDWARD P~ESSMA.N PRODUCTIONS January 31, 1987 1 • EXT. WALL STREET - EARLY MORNING FADE IN. THE STREET. The most famous third of a mile in the world. Towering landmark structures nearly blot out the dreary grey flannel sky. The morning rush hour crowds swarm through the dark, narrow streets like mice in a maze, all in pursuit of one thing: MONEY... CREDITS run. INT. SUBWAYPLATFORM - EARLY MORNING we hear the ROAR of the trains pulling out of the station. Blurred faces, bodies, suits, hats, attache cases float into view pressed like sardines against the sides of a door which now open, releasing an outward velocity of anger and greed, one of them JOE FOX. EXT. SUBWAYEXIT - MORNING The bubbling mass charges up the stairs. Steam rising from a grating, shapes merging into the crowd. Past the HOMELESS VETS, the insane BAG LADY with 12 cats and 20 shopping bags huddled in the corner of Trinity Church .•. Joe the Fox straggling behind, in a crumpied raincoat, tie askew, young, very young, his bleary face buried in~ Wall Street Journal, as he crosses the street against the light. JOE Why Fox? Why didn't you buy ... schmuck A car honks, swerving past. INT. OFFICE BUILDING - DAY Cavernous modern lobby. Bodies cramming into elevators. Joe, stuffing the newspaper into his coat, jams in. INT. ELEVATOR - MORNING Blank faces stare ahead, each lost in private thoughts, Joe again mouthing the thought, "stupid schmuck", his· ,:yes catching a blonde executive who quickly flicks her eyes away.