A Marine and Estuarine Habitat Classification System For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FALL 2016 Newsletter of the Washington Chapter of the Wildlife Society

Page | 1 The WashingtonTHE WASHINGTON WILDLIFER Wildlifer FALL 2016 Newsletter of the Washington Chapter of The Wildlife Society MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT meeting. During the banquet at the annual meeting each year Danielle Munzing we give out awards to biologists, organizations, and landowners. The last couple of years I have been involved Happy Fall, Wildlife Society with WA-TWS, I have been surprised that we haven’t members! Time for wool socks, a hot received more nominations. Last month during our board drink in the thermos, and dark skies at meeting, I asked everyone to do some homework and I would 1630. Across Washington, wildlife like to ask the same of each of you. biologists will be busy with their winter work, whether it’s surveying Do you know someone who deserves to be recognized? big game, writing reports, or planning Consider nominating that person for the 2017 awards season. the 2017 annual conference. That’s right, your Washington There are EIGHT different awards available from the Chapter is hard at work with the Washington State Society of Chapter. American Foresters to bring you an incredible 4 days of I think many of us know someone who: workshops, speaker sessions, delicious food, and opportunities to socialize and network. All of this will be Does more than they need to taking place in the heart of Central Washington, at the Red Makes valuable and unique contributions to wildlife Lion Hotel and Convention Center in Yakima. The theme for conservation this year is Forests and Wildlife: Responding to Change. Uses foresight to address problems early As you can imagine, there will be a lot to talk about and we Shows their dedication are bringing together experts in both forestry and wildlife to Shows exceptional leadership inspire discussions ranging from white-nose syndrome to Established partnerships that would not have existed forest health and ecological integrity and so much more. -

HELCOM Red List

SPECIES INFORMATION SHEET Corophium multisetosum English name: Scientific name: – Corophium multisetosum Taxonomical group: Species authority: Class: Malacostraca Stock, 1952 Order: Amphipoda Family: Corophiidae Subspecies, Variations, Synonyms: Generation length: 2 years? Trophonopsis truncata Strøm, 1768 Trophon truncatus Strøm, 1768 Past and current threats (Habitats Directive Future threats (Habitats Directive article 17 article 17 codes): Fishing (bottom trawling; codes): Fishing (bottom trawling; F02.02.01), F02.02.01), Eutrophication (H01.05) Eutrophication (H01.05) IUCN Criteria: HELCOM Red List NT B2b Category: Near Threatened Global / European IUCN Red List Category Habitats Directive: – – Protection and Red List status in HELCOM countries: Denmark –/–, Estonia –/–, Finland –/–, Germany –/G (endangered by unknown extent), Latvia –/–, Lithuania –/–-, Poland –/–, Russia –/–, Sweden: –/– Distribution and status in the Baltic Sea region C. multisetosum is reported mainly from coastal waters (bays) along southern shores of the Baltic Sea and those in the Danish straits, including adjacent fjords, canals, lagoons, e.g. the Curonian Lagoon, which is the easternmost area. However, there are also records from more open sea, and thus more saline areas such as the Hevring Bay, Arhus Bay, Arkona Basin by Darss-Zingst Peninsula, and the outer Puck Bay. Declining population trends are reported from the Szczecin Lagoon (Wawrzyniak-Wydrowska, pers. comm.). ©HELCOM Red List Benthic Invertebrate Expert Group 2013 www.helcom.fi > Baltic Sea trends > Biodiversity > Red List of species SPECIES INFORMATION SHEET Corophium multisetosum Distribution map The georeferenced records of species compiled from the Danish national database for marine data (MADS), Russian monitoring data (Elena Ezhova, pers. comm), and the database of the Leibniz Institute for Baltic Sea Research (IOW), where also the Polish literature and monitoring data for the species are stored. -

New Species, Corallivory, in Situ Video Observations and Overview of the Goniasteridae (Valvatida, Asteroidea) in the Hawaiian Region

Zootaxa 3926 (2): 211–228 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2015 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3926.2.3 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:39FE0179-9D06-4FC2-9465-CE69D79B933F New species, corallivory, in situ video observations and overview of the Goniasteridae (Valvatida, Asteroidea) in the Hawaiian Region CHRISTOPHER L. MAH Dept. of Invertebrate Zoology, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. 20007 Abstract Two new species of Goniasteridae, Astroceramus eldredgei n. sp. and Apollonaster kelleyi n. sp. are described from the Hawaiian Islands region. Prior to this occurrence, Apollonaster was known only from the North Atlantic. The Goniasteri- dae is the most diverse family of asteroids in the Hawaiian region. Additional in situ observations of several goniasterid species, including A. eldredgei n. sp. are reported. These observations extend documentation of deep-sea corallivory among goniasterid asteroids. New species occurrences presented herein suggested further biogeographic affinities be- tween tropical Pacific and Atlantic goniasterid faunas. Key words: Goniasteridae, Valvatida, deep-sea, Hawaiian Islands, predation Introduction Recent discoveries of new genera and species from deep-sea habitats along with new in situ video observations have provided us with new ecological insight into these poorly understood and formerly inaccessible settings (e.g., Mah et al. 2010, 2014; Mah & Foltz 2014). Hawaiian deep-sea Asteroidea are taxonomically diverse and occur in an active area of oceanographic and biological research (Chave and Malahoff 1998). New data on asteroids in this area presents an opportunity to review and highlight this diverse fauna. -

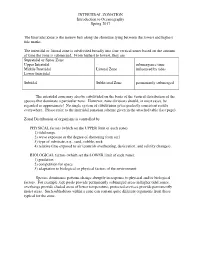

INTERTIDAL ZONATION Introduction to Oceanography Spring 2017 The

INTERTIDAL ZONATION Introduction to Oceanography Spring 2017 The Intertidal Zone is the narrow belt along the shoreline lying between the lowest and highest tide marks. The intertidal or littoral zone is subdivided broadly into four vertical zones based on the amount of time the zone is submerged. From highest to lowest, they are Supratidal or Spray Zone Upper Intertidal submergence time Middle Intertidal Littoral Zone influenced by tides Lower Intertidal Subtidal Sublittoral Zone permanently submerged The intertidal zone may also be subdivided on the basis of the vertical distribution of the species that dominate a particular zone. However, zone divisions should, in most cases, be regarded as approximate! No single system of subdivision gives perfectly consistent results everywhere. Please refer to the intertidal zonation scheme given in the attached table (last page). Zonal Distribution of organisms is controlled by PHYSICAL factors (which set the UPPER limit of each zone): 1) tidal range 2) wave exposure or the degree of sheltering from surf 3) type of substrate, e.g., sand, cobble, rock 4) relative time exposed to air (controls overheating, desiccation, and salinity changes). BIOLOGICAL factors (which set the LOWER limit of each zone): 1) predation 2) competition for space 3) adaptation to biological or physical factors of the environment Species dominance patterns change abruptly in response to physical and/or biological factors. For example, tide pools provide permanently submerged areas in higher tidal zones; overhangs provide shaded areas of lower temperature; protected crevices provide permanently moist areas. Such subhabitats within a zone can contain quite different organisms from those typical for the zone. -

Diversity and Phylogeography of Southern Ocean Sea Stars (Asteroidea)

Diversity and phylogeography of Southern Ocean sea stars (Asteroidea) Thesis submitted by Camille MOREAU in fulfilment of the requirements of the PhD Degree in science (ULB - “Docteur en Science”) and in life science (UBFC – “Docteur en Science de la vie”) Academic year 2018-2019 Supervisors: Professor Bruno Danis (Université Libre de Bruxelles) Laboratoire de Biologie Marine And Dr. Thomas Saucède (Université Bourgogne Franche-Comté) Biogéosciences 1 Diversity and phylogeography of Southern Ocean sea stars (Asteroidea) Camille MOREAU Thesis committee: Mr. Mardulyn Patrick Professeur, ULB Président Mr. Van De Putte Anton Professeur Associé, IRSNB Rapporteur Mr. Poulin Elie Professeur, Université du Chili Rapporteur Mr. Rigaud Thierry Directeur de Recherche, UBFC Examinateur Mr. Saucède Thomas Maître de Conférences, UBFC Directeur de thèse Mr. Danis Bruno Professeur, ULB Co-directeur de thèse 2 Avant-propos Ce doctorat s’inscrit dans le cadre d’une cotutelle entre les universités de Dijon et Bruxelles et m’aura ainsi permis d’élargir mon réseau au sein de la communauté scientifique tout en étendant mes horizons scientifiques. C’est tout d’abord grâce au programme vERSO (Ecosystem Responses to global change : a multiscale approach in the Southern Ocean) que ce travail a été possible, mais aussi grâce aux collaborations construites avant et pendant ce travail. Cette thèse a aussi été l’occasion de continuer à aller travailler sur le terrain des hautes latitudes à plusieurs reprises pour collecter les échantillons et rencontrer de nouveaux collègues. Par le biais de ces trois missions de recherches et des nombreuses conférences auxquelles j’ai activement participé à travers le monde, j’ai beaucoup appris, tant scientifiquement qu’humainement. -

List of Animal Species with Ranks October 2017

Washington Natural Heritage Program List of Animal Species with Ranks October 2017 The following list of animals known from Washington is complete for resident and transient vertebrates and several groups of invertebrates, including odonates, branchipods, tiger beetles, butterflies, gastropods, freshwater bivalves and bumble bees. Some species from other groups are included, especially where there are conservation concerns. Among these are the Palouse giant earthworm, a few moths and some of our mayflies and grasshoppers. Currently 857 vertebrate and 1,100 invertebrate taxa are included. Conservation status, in the form of range-wide, national and state ranks are assigned to each taxon. Information on species range and distribution, number of individuals, population trends and threats is collected into a ranking form, analyzed, and used to assign ranks. Ranks are updated periodically, as new information is collected. We welcome new information for any species on our list. Common Name Scientific Name Class Global Rank State Rank State Status Federal Status Northwestern Salamander Ambystoma gracile Amphibia G5 S5 Long-toed Salamander Ambystoma macrodactylum Amphibia G5 S5 Tiger Salamander Ambystoma tigrinum Amphibia G5 S3 Ensatina Ensatina eschscholtzii Amphibia G5 S5 Dunn's Salamander Plethodon dunni Amphibia G4 S3 C Larch Mountain Salamander Plethodon larselli Amphibia G3 S3 S Van Dyke's Salamander Plethodon vandykei Amphibia G3 S3 C Western Red-backed Salamander Plethodon vehiculum Amphibia G5 S5 Rough-skinned Newt Taricha granulosa -

Revised Essd-2020-161 (20 September 2020)

1 1 Half-hourly changes in intertidal temperature at nine wave-exposed 2 locations along the Atlantic Canadian coast: a 5.5-year study 3 Ricardo A. Scrosati, Julius A. Ellrich, Matthew J. Freeman 4 Department of Biology, St. Francis Xavier University, Antigonish, Nova Scotia B2G 2W5, Canada 5 Correspondence to: Ricardo A. Scrosati ([email protected]) 6 Abstract. Intertidal habitats are unique because they spend alternating periods of 7 submergence (at high tide) and emergence (at low tide) every day. Thus, intertidal temperature 8 is mainly driven by sea surface temperature (SST) during high tides and by air temperature 9 during low tides. Because of that, the switch from high to low tides and viceversa can determine 10 rapid changes in intertidal thermal conditions. On cold-temperate shores, which are 11 characterized by cold winters and warm summers, intertidal thermal conditions can also change 12 considerably with seasons. Despite this uniqueness, knowledge on intertidal temperature 13 dynamics is more limited than for open seas. This is especially true for wave-exposed intertidal 14 habitats, which, in addition to the unique properties described above, are also characterized by 15 wave splash being able to moderate intertidal thermal extremes during low tides. To address this 16 knowledge gap, we measured temperature every half hour during a period of 5.5 years (2014- 17 2019) at nine wave-exposed rocky intertidal locations along the Atlantic coast of Nova Scotia, 18 Canada. This data set is freely available from the figshare online repository (Scrosati and 19 Ellrich, 2020a; https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12462065.v1). -

PROTISTS Shore and the Waves Are Large, Often the Largest of a Storm Event, and with a Long Period

(seas), and these waves can mobilize boulders. During this phase of the storm the rapid changes in current direction caused by these large, short-period waves generate high accelerative forces, and it is these forces that ultimately can move even large boulders. Traditionally, most rocky-intertidal ecological stud- ies have been conducted on rocky platforms where the substrate is composed of stable basement rock. Projec- tiles tend to be uncommon in these types of habitats, and damage from projectiles is usually light. Perhaps for this reason the role of projectiles in intertidal ecology has received little attention. Boulder-fi eld intertidal zones are as common as, if not more common than, rock plat- forms. In boulder fi elds, projectiles are abundant, and the evidence of damage due to projectiles is obvious. Here projectiles may be one of the most important defi ning physical forces in the habitat. SEE ALSO THE FOLLOWING ARTICLES Geology, Coastal / Habitat Alteration / Hydrodynamic Forces / Wave Exposure FURTHER READING Carstens. T. 1968. Wave forces on boundaries and submerged bodies. Sarsia FIGURE 6 The intertidal zone on the north side of Cape Blanco, 34: 37–60. Oregon. The large, smooth boulders are made of serpentine, while Dayton, P. K. 1971. Competition, disturbance, and community organi- the surrounding rock from which the intertidal platform is formed zation: the provision and subsequent utilization of space in a rocky is sandstone. The smooth boulders are from a source outside the intertidal community. Ecological Monographs 45: 137–159. intertidal zone and were carried into the intertidal zone by waves. Levin, S. A., and R. -

THE REVIEW of ECOLOGICAL and GENETIC RESEARCH of PONTO-CASPIAN GOBIES (Pisces, Gobiidae) in EUROPE

Croatian Journal of Fisheries, 2016, 74, 110-123 G. Jakšić et al: Ecological and genetic research of Ponto-Caspian gobies DOI: 10.1515/cjf-2016-0015 CODEN RIBAEG ISSN 1330-061X (print), 1848-0586 (online) THE REVIEW OF ECOLOGICAL AND GENETIC RESEARCH OF PONTO-CASPIAN GOBIES (Pisces, Gobiidae) IN EUROPE Goran Jakšić1, *, Margita Jadan2, Marina Piria3 1City of Karlovac, Banjavčićeva 9, 47000 Karlovac, Croatia 2Division of materials chemistry, Ruđer Bošković Institute, Bijenička 54, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia 3University of Zagreb, Faculty of Agriculture, Department of Fisheries, Beekeeping, Game management and Special Zoology, Svetošimunska 25, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia *Corresponding Author, Email: [email protected] ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Received: 27 January 2016 Invasive Ponto-Caspian gobies (monkey goby Neogobius fluviatilis, round Received in revised form: 14 May 2016 goby Neogobius melanostomus and bighead goby Ponticola kessleri) have Accepted: 20 May 2016 recently caused dramatic changes in fish assemblage structure throughout Available online: 24 May 2016 European river systems. This review provides summary of recent research on their dietary habits, age and growth, phylogenetic lineages and gene diversity. The principal food of all three species is invertebrates, and more rarely fish, which depends on the type of habitat, part of the year, as well as the morphological characteristics of species. According to the von Bertalanffy growth model, size at age is specific for the region, but due to its disadvantages it is necessary to test other growth models. Phylogenetic Keywords: analysis of monkey goby and round goby indicates separation between the European river systems Black Sea and the Caspian Sea haplotypes. The greatest genetic diversity is Invasive gobies found among populations of the Black Sea, and the lowest among European Ecology invaders. -

The Biology of Seashores - Image Bank Guide All Images and Text ©2006 Biomedia ASSOCIATES

The Biology of Seashores - Image Bank Guide All Images And Text ©2006 BioMEDIA ASSOCIATES Shore Types Low tide, sandy beach, clam diggers. Knowing the Low tide, rocky shore, sandstone shelves ,The time and extent of low tides is important for people amount of beach exposed at low tide depends both on who collect intertidal organisms for food. the level the tide will reach, and on the gradient of the beach. Low tide, Salt Point, CA, mixed sandstone and hard Low tide, granite boulders, The geology of intertidal rock boulders. A rocky beach at low tide. Rocks in the areas varies widely. Here, vertical faces of exposure background are about 15 ft. (4 meters) high. are mixed with gentle slopes, providing much variation in rocky intertidal habitat. Split frame, showing low tide and high tide from same view, Salt Point, California. Identical views Low tide, muddy bay, Bodega Bay, California. of a rocky intertidal area at a moderate low tide (left) Bays protected from winds, currents, and waves tend and moderate high tide (right). Tidal variation between to be shallow and muddy as sediments from rivers these two times was about 9 feet (2.7 m). accumulate in the basin. The receding tide leaves mudflats. High tide, Salt Point, mixed sandstone and hard rock boulders. Same beach as previous two slides, Low tide, muddy bay. In some bays, low tides expose note the absence of exposed algae on the rocks. vast areas of mudflats. The sea may recede several kilometers from the shoreline of high tide Tides Low tide, sandy beach. -

OREGON ESTUARINE INVERTEBRATES an Illustrated Guide to the Common and Important Invertebrate Animals

OREGON ESTUARINE INVERTEBRATES An Illustrated Guide to the Common and Important Invertebrate Animals By Paul Rudy, Jr. Lynn Hay Rudy Oregon Institute of Marine Biology University of Oregon Charleston, Oregon 97420 Contract No. 79-111 Project Officer Jay F. Watson U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 500 N.E. Multnomah Street Portland, Oregon 97232 Performed for National Coastal Ecosystems Team Office of Biological Services Fish and Wildlife Service U.S. Department of Interior Washington, D.C. 20240 Table of Contents Introduction CNIDARIA Hydrozoa Aequorea aequorea ................................................................ 6 Obelia longissima .................................................................. 8 Polyorchis penicillatus 10 Tubularia crocea ................................................................. 12 Anthozoa Anthopleura artemisia ................................. 14 Anthopleura elegantissima .................................................. 16 Haliplanella luciae .................................................................. 18 Nematostella vectensis ......................................................... 20 Metridium senile .................................................................... 22 NEMERTEA Amphiporus imparispinosus ................................................ 24 Carinoma mutabilis ................................................................ 26 Cerebratulus californiensis .................................................. 28 Lineus ruber ......................................................................... -

Humboldt Bay Fishes

Humboldt Bay Fishes ><((((º>`·._ .·´¯`·. _ .·´¯`·. ><((((º> ·´¯`·._.·´¯`·.. ><((((º>`·._ .·´¯`·. _ .·´¯`·. ><((((º> Acknowledgements The Humboldt Bay Harbor District would like to offer our sincere thanks and appreciation to the authors and photographers who have allowed us to use their work in this report. Photography and Illustrations We would like to thank the photographers and illustrators who have so graciously donated the use of their images for this publication. Andrey Dolgor Dan Gotshall Polar Research Institute of Marine Sea Challengers, Inc. Fisheries And Oceanography [email protected] [email protected] Michael Lanboeuf Milton Love [email protected] Marine Science Institute [email protected] Stephen Metherell Jacques Moreau [email protected] [email protected] Bernd Ueberschaer Clinton Bauder [email protected] [email protected] Fish descriptions contained in this report are from: Froese, R. and Pauly, D. Editors. 2003 FishBase. Worldwide Web electronic publication. http://www.fishbase.org/ 13 August 2003 Photographer Fish Photographer Bauder, Clinton wolf-eel Gotshall, Daniel W scalyhead sculpin Bauder, Clinton blackeye goby Gotshall, Daniel W speckled sanddab Bauder, Clinton spotted cusk-eel Gotshall, Daniel W. bocaccio Bauder, Clinton tube-snout Gotshall, Daniel W. brown rockfish Gotshall, Daniel W. yellowtail rockfish Flescher, Don american shad Gotshall, Daniel W. dover sole Flescher, Don stripped bass Gotshall, Daniel W. pacific sanddab Gotshall, Daniel W. kelp greenling Garcia-Franco, Mauricio louvar