JAY ZOLA and JERIMIAH JOSEPH LOWNEY, Plaintiffs, Vs. TD

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DELIVERY INSTRUCTIONS: Clearing Firm: TD Ameritrade Clearing, Inc

DELIVERY INSTRUCTIONS: Clearing Firm: TD Ameritrade Clearing, Inc. Wire Instructions Tax ID Number: 47-0533629 If your financial institution is located in the United States, wire to: TD Ameritrade, Inc. Wells Fargo Bank, NA Attn: Transfer of Accounts Department 420 Montgomery Street 200 S 108th Ave San Francisco, CA 94104 Omaha, NE 68154-2631 ABA transit routing # 121000248 Delivery Instructions: For credit to: All deliveries MUST include Client Name and TD Ameritrade Clearing, Inc. TD Ameritrade Account Number. Account # 4123214561 Depository Trust Company: DTC #0188 *For benefit of: Federal Book Entry: Your nine-digit TD Ameritrade account number BK of NYC/Ameritrade Your name ABA #021000018 Your address Book Entry GNMA Securities: * Required for timely and accurate processing of your wire request. PTC Instructions are: BKNYCATP If your financial institution is located outside the United States, Mutual Fund Registration: wire to: TD Ameritrade, Inc. First National Bank of Omaha Tax ID Number: 47-0533629 16th & Dodge Streets FBO Client’s Name and Account Number Omaha, NE 68102 PO Box 2226 ABA # 104000016 Omaha, NE 68103-2226 Swift Code / BIC: FNBOUS44XXX (If your bank requires it) Broker/Dealer: TD Ameritrade, Inc. For credit to: Options Clearing Corporation: OCC #0777 TD Ameritrade Clearing, Inc. A/C # 16424641 Forward Checks and Physical Certificates: TD Ameritrade Clearing, Inc. *For benefit of: FBO Client Name and Account Number Your nine-digit TD Ameritrade account number PO Box 2226 Your name Omaha, NE 68103-2226 Your address * Required for timely and accurate processing of your wire request. Or to: 200 S 108th Ave Contact TD Ameritrade, and not the banks, with questions or Omaha, NE 68154-2631 concerns about wire transfers. -

DTC Participant Alphabetical Listing June 2019.Xlsx

DTC PARTICPANT REPORT (Alphabetical Sort ) Month Ending - June 30, 2019 PARTICIPANT ACCOUNT NAME NUMBER ABN AMRO CLEARING CHICAGO LLC 0695 ABN AMRO SECURITIES (USA) LLC 0349 ABN AMRO SECURITIES (USA) LLC/A/C#2 7571 ABN AMRO SECURITIES (USA) LLC/REPO 7590 ABN AMRO SECURITIES (USA) LLC/ABN AMRO BANK NV REPO 7591 ALPINE SECURITIES CORPORATION 8072 AMALGAMATED BANK 2352 AMALGAMATED BANK OF CHICAGO 2567 AMHERST PIERPONT SECURITIES LLC 0413 AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INVESTMENT SERVICES INC. 0756 AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INVESTMENT SERVICES INC./CONDUIT 7260 APEX CLEARING CORPORATION 0158 APEX CLEARING CORPORATION/APEX CLEARING STOCK LOAN 8308 ARCHIPELAGO SECURITIES, L.L.C. 0436 ARCOLA SECURITIES, INC. 0166 ASCENSUS TRUST COMPANY 2563 ASSOCIATED BANK, N.A. 2257 ASSOCIATED BANK, N.A./ASSOCIATED TRUST COMPANY/IPA 1620 B. RILEY FBR, INC 9186 BANCA IMI SECURITIES CORP. 0136 BANK OF AMERICA, NATIONAL ASSOCIATION 2236 BANK OF AMERICA, NA/GWIM TRUST OPERATIONS 0955 BANK OF AMERICA/LASALLE BANK NA/IPA, DTC #1581 1581 BANK OF AMERICA NA/CLIENT ASSETS 2251 BANK OF CHINA, NEW YORK BRANCH 2555 BANK OF CHINA NEW YORK BRANCH/CLIENT CUSTODY 2656 BANK OF MONTREAL, CHICAGO BRANCH 2309 BANKERS' BANK 2557 BARCLAYS BANK PLC NEW YORK BRANCH 7263 BARCLAYS BANK PLC NEW YORK BRANCH/BARCLAYS BANK PLC-LNBR 8455 BARCLAYS CAPITAL INC. 5101 BARCLAYS CAPITAL INC./LE 0229 BB&T SECURITIES, LLC 0702 BBVA SECURITIES INC. 2786 BETHESDA SECURITIES, LLC 8860 # DTCC Confidential (Yellow) DTC PARTICPANT REPORT (Alphabetical Sort ) Month Ending - June 30, 2019 PARTICIPANT ACCOUNT NAME NUMBER BGC FINANCIAL, L.P. 0537 BGC FINANCIAL L.P./BGC BROKERS L.P. 5271 BLOOMBERG TRADEBOOK LLC 7001 BMO CAPITAL MARKETS CORP. -

TD Ameritrade Prohibitions on Sales of AMC Stock Complaint

8:21-cv-00093-RFR-MDN Doc # 1 Filed: 03/08/21 Page 1 of 25 - Page ID # 1 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF NEBRASKA FRANCIS SHAEFFER, individually, and on behalf No. of all others similarly situated, Plaintiff, Class Action Complaint v. Jury Trial Demanded TD AMERITRADE, INC., Defendant. Francis Shaeffer sues TD Ameritrade, Inc. (“TD” or “Defendant”) for violations of contractual duties under Nebraska state law. He sues on his own behalf and on behalf of all others similarly situated. Mr. Shaeffer (“Plaintiff”) alleges: NATURE OF THE CASE 1. Plaintiff asserts this nationwide class action on behalf of all TD brokerage account customers who attempted to sell AMC securities through TD’s trading platform and were prohibited from doing or delayed in doing so on January 28, 2021, and who sustained damages as a result. Plaintiff brings this action for breaches of contract and implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing. The contracts and covenant are governed by Nebraska law. 2. TD used its power as a securities broker, along with its platform’s, and on-line trading devices, tools and equipment, to block Plaintiff and members of Plaintiff’s putative class who are TD account holders from trading stock in AMC Entertainment Holding, Inc., a company whose securities are traded on the New York Stock Exchange under the symbol (“AMC”). TD did so deliberately during a “short squeeze” market condition that was fully 1 8:21-cv-00093-RFR-MDN Doc # 1 Filed: 03/08/21 Page 2 of 25 - Page ID # 2 known to TD. -

Who We Are by the Numbers | TD Ameritrade Institutional

Fact Sheet Who we are by the numbers TD Ameritrade Holding Corporation Our history FY2020 3rd quarter highlights 1975 First Omaha Securities, Inc. is formed. 1983 Ameritrade Clearing, Inc. is established, providing correspondent clearing $107B $1.461T services for broker-dealers NET NEW and Registered Investment ASSETS CLIENT ASSETS Advisors. 1988 The company is the first to offer automated trades via touch-tone phone. 1995 The company acquires K. Aufhauser & Co, the 2.17M first credited with offering DAILY AVERAGE 10,000 online trading in 1994. REVENUE TRADES EMPLOYEES 1998 The company acquires (DARTS) Jack White & Company, one of the nation’s leading discount brokerages. 1999 Ameritrade is the first to offer trading via mobile device, with Credit ratings the SprintPCS® Wireless Web. 2001 Ameritrade acquires National Discount Brokers Corporation, kicking off a decade of Moody’s S&P industry consolidation. 2002 Ameritrade merges with A2 A Datek Online Holdings to become the largest brokerage firm in average trades per day. 2003 Ameritrade offers the Committed to diversity and inclusion industry’s first trade execution guarantee of 10 seconds. Human Rights Campaign Foundation’s 2006 Ameritrade acquires Corporate Equality Index (2016–2020) TD Waterhouse USA from TD Bank Financial Group 100% and becomes TD Ameritrade. 2009 TD Ameritrade acquires thinkorswim Group Inc. 2017 TD Ameritrade acquires Scottrade. Fact Sheet Who we are and where we’ve been In 1975, the SEC allowed brokers to choose how much they charged to place a trade. Many established firms held fast to their old, exclusive ways, while new start-ups, like TD Ameritrade, opted for something different. -

IDA Program Banks-TDA 0721

IDA Program Banks The following list identifies the “Program Banks” that are a part of the TD Ameritrade FDIC Insured Deposit Account (IDA) program. Available cash will be deposited into one or more Program Banks up to $247,500 per Program Bank, per depositor, per legal capacity, except for “the Excess Bank” which will receive deposits without limit, even if the amount in the IDA exceeds the FDIC insurance available to you. The “Excess Bank” is denoted below with an asterisk (*). Any deposits (including certificates of deposit) that you maintain in the same insurable capacity directly with a Program Bank, or through an intermediary (such as us or another broker), will be aggregated with deposits in your IDA at such Program Bank for purposes of determining your maximum FDIC insurance amount. You are responsible for monitoring the total amount of deposits that you maintain at the Program Banks in order to determine the extent of FDIC coverage available to you. – TD Bank N.A. (“TD Bank”) – TD Bank USA N.A. (“TD Bank USA”) – US Bank N.A. (“US Bank”) – Citibank, N.A. (“Citibank”) – Wells Fargo Bank, N.A. (“Wells Fargo”) – Synchrony Bank (“Synchrony Bank”) – Bank of America N.A. (“Bank of America”) – * Charles Schwab Bank, SSB (“Schwab Bank”) – Charles Schwab Premier Bank, SSB (“Schwab Premier Bank”) – Charles Schwab Trust Bank (“Schwab Trust Bank”) TD Ameritrade, Schwab Bank, Schwab Premier Bank, and Schwab Trust Bank are affiliated through their parent company. TD Ameritrade is not affiliated with any other Program Bank. TD Ameritrade, Inc., member FINRA/SIPC, a subsidiary of The Charles Schwab Corporation. -

1 Hearing Before the United States House Of

HEARING BEFORE THE UNITED STATES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES COMMITTEE ON FINANCIAL SERVICES February 18, 2021 Testimony of Vladimir Tenev Robinhood Markets, Inc. I. Introduction Chairwoman Waters, Ranking Member McHenry, and Members of the Committee: My name is Vlad Tenev, and I am the co-founder and CEO of Robinhood Markets, Inc.1 Thank you for the opportunity to speak with you today about Robinhood and the millions of individual investors we serve. Robinhood has changed the investing world for the better. We pioneered a mobile-first investing platform that allows our customers to trade stocks, exchange-traded funds (“ETFs”), options, and other investments with no trading commissions and no account minimums. By taking down these traditional barriers to investing and creating an accessible and intuitive platform, Robinhood opened up the markets to millions of retail investors. 1 It is common in the financial services industry for broker-dealer firms’ operations to be subsidiaries of a larger holding company, as is the case with Robinhood. Robinhood Markets, Inc. (“Robinhood Markets”) is an American financial services company headquartered in Menlo Park, California. Robinhood Markets wholly owns Robinhood Financial, LLC (“Robinhood Financial”), Robinhood Securities, LLC (“Robinhood Securities”), and Robinhood Crypto, LLC (“Robinhood Crypto”). Robinhood Financial acts as an introducing broker for our customers by taking their trade orders. Robinhood Securities, a member SEC-registered clearinghouse, serves as a clearing broker for Robinhood Financial. In that capacity, Robinhood Securities executes customer orders received from Robinhood Financial by routing them to market-makers. Robinhood Securities also clears and settles customer trades. Robinhood Crypto facilitates cryptocurrency trading. -

Focus on TD Bank, America's Most Convenient Bank June 16, 2010 TD

TD BANK FINANCIAL GROUP INVESTOR DAY Focus on TD Bank, America’s Most Convenient Bank June 16, 2010 Caution regarding forward-looking statements The information presented may contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995 and comparable “safe harbour” provisions of applicable Canadian legislation, including, but not limited to, statements relating to anticipated financial and operating results, the companies’ plans, objectives, expectations and intentions, cost savings and other statements, including words such as “anticipate,” “believe,” “plan,” “estimate,” “expect,” “intend,” “will,” “should,” “may,” and other similar expressions. Such statements are based upon the current beliefs and expectations of our management and involve a number of significant risks and uncertainties. Actual results may differ materially from the results anticipated in these forward-looking statements. The following factors, among others, could cause or contribute to such material differences: the ability to obtain the approval of the transaction by The South Financial Group, Inc. shareholders; the ability to realize the expected synergies resulting from the transaction in the amounts or in the timeframe anticipated; the ability to integrate The South Financial Group, Inc.’s businesses into those of The Toronto-Dominion Bank in a timely and cost-efficient manner; and the ability to obtain governmental approvals of the transaction or to satisfy other conditions to the transaction on the proposed terms and timeframe. Additional factors that could cause The Toronto-Dominion Bank’s and The South Financial Group, Inc.’s results to differ materially from those described in the forward-looking statements can be found in the 2009 Annual Report on Form 40−F for The Toronto-Dominion Bank and the 2009 Annual Report on Form 10−K of The South Financial Group, Inc. -

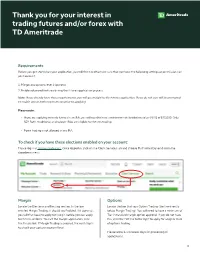

Thank You for Your Interest in Trading Futures And/Or Forex with TD Ameritrade

Thank you for your interest in trading futures and/or forex with TD Ameritrade Requirements Before you get started on your application, you will first need to make sure that you have the following settings or permissions on your account: 1. Margin and options level 2 approval 2. Enable advanced features during the futures application process Note: If you already have these requirements, you will go straight to the futures application. If you do not, you will be prompted to enable one or both requirements prior to applying Please note: • If you are applying to trade futures in an IRA, you will need to have a minimum net liquidation value (NLV) of $25,000. Only SEP, Roth, traditional, and rollover IRAs are eligible for futures trading. • Forex trading is not allowed in any IRA To check if you have these elections enabled on your account: Please log in at tdameritrade.com. Once logged in, click on the Client Services tab and choose My Profile (General) from the dropdown menu. Margin Options Locate the Elections and Routing section. In the line Locate the line that says Option Trading (the line directly entitled Margin Trading, it should say Enabled. If it does not, below Margin Trading). You will need to have a minimum of you will first need to apply for margin before you can apply Tier 2 standard margin option approval. If you do not have for futures or forex. To start the margin application, click this, click the Edit link to the right to apply for a higher level the Enable link. -

Numerical.Pdf

DTC PARTICPANT REPORT (Numerical Sort ) Month Ending - July 31, 2021 NUMBER PARTICIPANT ACCOUNT NAME 0 SERIES 0005 GOLDMAN SACHS & CO. LLC 0010 BROWN BROTHERS HARRIMAN & CO. 0013 SANFORD C. BERNSTEIN & CO., LLC 0015 MORGAN STANLEY SMITH BARNEY LLC 0017 INTERACTIVE BROKERS LLC 0019 JEFFERIES LLC 0031 NATIXIS SECURITIES AMERICAS LLC 0032 DEUTSCHE BANK SECURITIES INC.- STOCK LOAN 0033 COMMERZ MARKETS LLC/FIXED INC. REPO & COMM. PAPER 0045 BMO CAPITAL MARKETS CORP. 0046 PHILLIP CAPITAL INC./STOCK LOAN 0050 MORGAN STANLEY & CO. LLC 0052 AXOS CLEARING LLC 0057 EDWARD D. JONES & CO. 0062 VANGUARD MARKETING CORPORATION 0063 VIRTU AMERICAS LLC/VIRTU FINANCIAL BD LLC 0065 ZIONS DIRECT, INC. 0067 INSTINET, LLC 0075 LPL FINANCIAL LLC 0076 MUFG SECURITIES AMERICAS INC. 0083 TRADEBOT SYSTEMS, INC. 0096 SCOTIA CAPITAL (USA) INC. 0099 VIRTU AMERICAS LLC/VIRTU ITG LLC 100 SERIES 0100 COWEN AND COMPANY LLC 0101 MORGAN STANLEY & CO LLC/SL CONDUIT 0103 WEDBUSH SECURITIES INC. 0109 BROWN BROTHERS HARRIMAN & CO./ETF 0114 MACQUARIE CAPITAL (USA) INC. 0124 INGALLS & SNYDER, LLC 0126 COMMERZ MARKETS LLC 0135 CREDIT SUISSE SECURITIES (USA) LLC/INVESTMENT ACCOUNT 0136 INTESA SANPAOLO IMI SECURITIES CORP. 0141 WELLS FARGO CLEARING SERVICES, LLC 0148 ICAP CORPORATES LLC 0158 APEX CLEARING CORPORATION 0161 BOFA SECURITIES, INC. 0163 NASDAQ BX, INC. 0164 CHARLES SCHWAB & CO., INC. 0166 ARCOLA SECURITIES, INC. 0180 NOMURA SECURITIES INTERNATIONAL, INC. 0181 GUGGENHEIM SECURITIES, LLC 0187 J.P. MORGAN SECURITIES LLC 0188 TD AMERITRADE CLEARING, INC. 0189 STATE STREET GLOBAL MARKETS, LLC 0197 CANTOR FITZGERALD & CO. / CANTOR CLEARING SERVICES 200 SERIES 0202 FHN FINANCIAL SECURITIES CORP. 0221 UBS FINANCIAL SERVICES INC. -

Firm Brochure October 1, 2020

ITEM 1 – COVER PAGE WAYFINDING FINANCIAL, LLC PART 2A – FIRM BROCHURE OCTOBER 1, 2020 WAYFINDING FINANCIAL, LLC 19020 33RD AVENUE, SUITE 390 LYNNWOOD, WA 98036 425-361-0707 This brochure provides information about the qualifications and business practices of Wayfinding Financial, LLC (“Wayfinding Financial”). If you have any questions about the contents of this brochure, please contact us at 425-361-0707. The information in this brochure has not been approved or verified by the United States Securities and Exchange Commission or by any state securities authority. Wayfinding Financial is a Registered Investment Adviser. Registration as an Investment Adviser with the United States Securities and Exchange Commission or any state securities authority does not imply a certain level of skill or training. Additional information about Wayfinding Financial, LLC is available on the SEC’s website at www.adviserinfo.sec.gov. You can search this site by a unique identifying number, known as an IARD number. The IARD number for Wayfinding Financial is IARD# 306208. ITEM 2 – MATERIAL CHANGES SUMMARY OF MATERIAL CHANGES This section of the Brochure will address only those “material changes” that have been incorporated since our last delivery or posting of this document on the SEC’s public disclosure website (IAPD) www.adviserinfo.sec.gov. Our firm was approved by the SEC in February 2020. The following updates have been made since our last ADV filing: • ITEM 4 and ITEM 14 have been updated to reflect the Marketing Services Agreement with SoFi Lending Corporations (“SoFi”). • ITEM 18 was updated to reflect receipt of Paycheck Protection Plan Loan through the SBA in conjunction with the relief afforded from the CARES Act. -

Funding Instructions-TDA 0721

Funding Instructions PO Box 2760 Omaha, NE 68103-2760 Fax: 866-468-6268 Thank you for your interest in funding a new or existing TD Ameritrade account! Below, you’ll find detailed instructions for the many funding options available to you. WAYS TO FUND YOUR TD AMERITRADE ACCOUNT Electronic Funding: For added convenience and accuracy, we recommend funding your account electronically—it’s easy, fast, and free. For complete instructions, see the Electronic Funding section below. Mailing a Check: A conventional way to fund your account—just be sure to include all the required information and ensure your check deposit is acceptable before sending it by mail. For complete instructions, see the Mailing a Check section below. Stock Certificate: Depositing a stock certificate into your account can be as simple as endorsing it and including a few key pieces of information. For complete instructions, see the Stock Certificate section of this document. Brokerage Transfer: Generally, there’s no need to sell stocks, bonds, and ETFs from another broker—just follow a few easy steps to transfer these and other holdings into your like-titled TD Ameritrade account. Be advised that most banks/brokerages will assess a transfer-out fee. For complete instructions, see the Brokerage Transfer section of this document. Wire Transfer: Quickly transfer funds to your account, often within the same business day, from nearly anywhere in the United States. However, most banks will assess a wire fee. For complete instructions, see the Wire Transfer section of this document. ELECTRONIC FUNDING Electronically linking your brokerage account to your bank account can make transferring money between accounts easy, fast, and free. -

ANNUAL REPORT March 31, 2014

ANNUAL REPORT March 31, 2014 METROPOLITAN WEST FUNDS Ultra Short Bond Fund Low Duration Bond Fund Intermediate Bond Fund Total Return Bond Fund High Yield Bond Fund Unconstrained Bond Fund Floating Rate Income Fund Strategic Income Fund AlphaTrak 500 Fund 2014 Metropolitan West Funds March 31, 2014 Table of Contents Letter to Shareholders..................................................................... 1 Fund Performance........................................................................ 7 Disclosure of Fund Expenses (Unaudited) ..................................................... 12 Summary of Portfolio Holdings ............................................................. 15 Schedule of Portfolio Investments ........................................................... 20 Ultra Short Bond Fund .................................................................. 20 Low Duration Bond Fund ................................................................ 29 Intermediate Bond Fund ................................................................. 46 Total Return Bond Fund ................................................................. 58 High Yield Bond Fund .................................................................. 94 Unconstrained Bond Fund ............................................................... 102 Floating Rate Income Fund .............................................................. 120 Strategic Income Fund .................................................................. 126 AlphaTrak 500 Fund...................................................................