The Diva Onscreen by Dolores C Mcelroy a Dissertation Submitted In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’S Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 10-3-2014 The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M. May University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation May, Joshua M., "The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 580. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/580 ABSTRACT The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua Michael May University of Connecticut, 2014 W. A. Mozart’s opera and concert arias for tenor are among the first music written specifically for this voice type as it is understood today, and they form an essential pillar of the pedagogy and repertoire for the modern tenor voice. Yet while the opera arias have received a great deal of attention from scholars of the vocal literature, the concert arias have been comparatively overlooked; they are neglected also in relation to their counterparts for soprano, about which a great deal has been written. There has been some pedagogical discussion of the tenor concert arias in relation to the correction of vocal faults, but otherwise they have received little scrutiny. This is surprising, not least because in most cases Mozart’s concert arias were composed for singers with whom he also worked in the opera house, and Mozart always paid close attention to the particular capabilities of the musicians for whom he wrote: these arias offer us unusually intimate insights into how a first-rank composer explored and shaped the potential of the newly-emerging voice type of the modern tenor voice. -

FY14 Tappin' Study Guide

Student Matinee Series Maurice Hines is Tappin’ Thru Life Study Guide Created by Miller Grove High School Drama Class of Joyce Scott As part of the Alliance Theatre Institute for Educators and Teaching Artists’ Dramaturgy by Students Under the guidance of Teaching Artist Barry Stewart Mann Maurice Hines is Tappin’ Thru Life was produced at the Arena Theatre in Washington, DC, from Nov. 15 to Dec. 29, 2013 The Alliance Theatre Production runs from April 2 to May 4, 2014 The production will travel to Beverly Hills, California from May 9-24, 2014, and to the Cleveland Playhouse from May 30 to June 29, 2014. Reviews Keith Loria, on theatermania.com, called the show “a tender glimpse into the Hineses’ rise to fame and a touching tribute to a brother.” Benjamin Tomchik wrote in Broadway World, that the show “seems determined not only to love the audience, but to entertain them, and it succeeds at doing just that! While Tappin' Thru Life does have some flaws, it's hard to find anyone who isn't won over by Hines showmanship, humor, timing and above all else, talent.” In The Washington Post, Nelson Pressley wrote, “’Tappin’ is basically a breezy, personable concert. The show doesn’t flinch from hard-core nostalgia; the heart-on-his-sleeve Hines is too sentimental for that. It’s frankly schmaltzy, and it’s barely written — it zips through selected moments of Hines’s life, creating a mood more than telling a story. it’s a pleasure to be in the company of a shameless, ebullient vaudeville heart.” Maurice Hines Is . -

Diva Forever the Operatic Voice Between Reproduction and Reception

ERIK STEINSKOG Diva Forever The Operatic Voice between Reproduction and Reception The operatic voice has been among the key dimensions within opera-studies for several years. Within a fi eld seemingly reinventing itself, however, this voice is intimately relat- ed to other dimensions: sound, the body, gender and sexuality, and so forth. One par- ticular voice highlighting these intersections is the diva’s voice. Somewhat paradoxical this is not least the case when this particular voice is recorded, stored, and replayed by way of technology. The technologically reproduced voice makes it possible to fully con- centrate on “the voice itself,” seemingly without paying any attention to other dimen- sions. The paradox thus arises that the above-mentioned intersections might be most clearly found when attempts are made to remove them from the scene of perception. The focus on “the voice itself” is familiar to readers of Michel Chion’s The Voice in Cinema. Starting out with stating that the voice is elusive, Chion asks what is left when one eliminates, from the voice, “everything that is not the voice itself.”1 Relating pri- marily to fi lm, and coming from a strong background in psychoanalysis, Chion moves on to discuss many features of the voice, beginning with the sometimes forgotten dif- ferentiation from speech. The materiality of the voice becomes important, and then already different intersections are hinted at. Combining Chion’s interpretations with musicology is nothing new, but it opens some other questions. The voice in music is not necessarily as elusive as Chion seems to argue, or, perhaps better, its elusiveness is of a different kind.2 And when it comes to the operatic voice, dimensions beyond the ones Chion discusses beckon a refl ection. -

Carol Raskin

Carol Raskin Artistic Images Make-Up and Hair Artists, Inc. Miami – Office: (305) 216-4985 Miami - Cell: (305) 216-4985 Los Angeles - Office: (310) 597-1801 FILMS DATE FILM DIRECTOR PRODUCTION ROLE 2019 Fear of Rain Castille Landon Pinstripe Productions Department Head Hair (Kathrine Heigl, Madison Iseman, Israel Broussard, Harry Connick Jr.) 2018 Critical Thinking John Leguizamo Critical Thinking LLC Department Head Hair (John Leguizamo, Michael Williams, Corwin Tuggles, Zora Casebere, Ramses Jimenez, William Hochman) The Last Thing He Wanted Dee Rees Elena McMahon Productions Additional Hair (Miami) (Anne Hathaway, Ben Affleck, Willem Dafoe, Toby Jones, Rosie Perez) Waves Trey Edward Shults Ultralight Beam LLC Key Hair (Sterling K. Brown, Kevin Harrison, Jr., Alexa Demie, Renee Goldsberry) The One and Only Ivan Thea Sharrock Big Time Mall Productions/Headliner Additional Hair (Bryan Cranston, Ariana Greenblatt, Ramon Rodriguez) (U. S. unit) 2017 The Florida Project Sean Baker The Florida Project, Inc. Department Head Hair (Willem Dafoe, Bria Vinaite, Mela Murder, Brooklynn Prince) Untitled Detroit City Yann Demange Detroit City Productions, LLC Additional Hair (Miami) (Richie Merritt Jr., Matthew McConaughey, Taylour Paige, Eddie Marsan, Alan Bomar Jones) 2016 Baywatch Seth Gordon Paramount Worldwide Additional Hair (Florida) (Dwayne Johnson, Zac Efron, Alexandra Daddario, David Hasselhoff) Production, Inc. 2015 The Infiltrator Brad Furman Good Films Production Department Head Hair (Bryan Cranston, John Leguizamo, Benjamin Bratt, Olympia -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

Kaiser Thesis Revised Final Bez Copyright Page

TRANSGENERATIONAL FECUNDITY COMPENSATION AND POST-PARASITISM REPRODUCTION BY APHIDS IN RESPONSE TO THEIR PARASITOIDS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY MATTHEW CHARLES KAISER IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GEORGE EUGENE HEIMPEL (ADVISOR) March 2017 © Matthew C Kaiser 2017 Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my advisor George Heimpel for his limitless support and encouragement over these years. It has been a true pleasure being a member of his lab group, where I have been surrounded by so many brilliant and sympathetic minds. Through him I gained a mentor, role model, and an outstanding jazz guitar player to jam with. I would also like to thank my advising committee members Drs. David Andow, Elizabeth Borer, and Emilie Snell-Rood for valuable feedback and guidance for improving my work. I thank everyone who has come and gone from our lab group and provided feedback, guidance and discussions of this work while I have been here, especially Dr. Mark Asplen, Dr. Mariana Bulgarella, Megan Carter, Dr. Jeremy Chacón, Dr. Nico Desneux, Dr. Christine Dieckhoff, Jonathan Dregni, Dr. Jim Eckberg, Hannah Gray, Dr. Thelma Heidel-Baker, Dr. Joe Kaser, Dr. Emily Mohl, Nick Padowski, Dr. Julie Peterson, Dr. Milan Plećaš, Anh Tran, Dr. J.J. Weis and Stephanie Wolf. Special thanks to Jonathan for ensuring plants, insects, supplies and chocolate were always there when needed. Thank you to Stephanie Dahl and everyone else behind the Minnesota Department of Agriculture quarantine facility here on campus, where the majority of this work was carried out. -

Cinematic Hamlet Arose from Two Convictions

INTRODUCTION Cinematic Hamlet arose from two convictions. The first was a belief, confirmed by the responses of hundreds of university students with whom I have studied the films, that theHamlet s of Lau- rence Olivier, Franco Zeffirelli, Kenneth Branagh, and Michael Almereyda are remarkably success- ful films.1 Numerous filmHamlet s have been made using Shakespeare’s language, but only the four included in this book represent for me out- standing successes. One might admire the fine acting of Nicol Williamson in Tony Richard- son’s 1969 production, or the creative use of ex- treme close-ups of Ian McKellen in Peter Wood’s Hallmark Hall of Fame television production of 1 Introduction 1971, but only four English-language films have thoroughly transformed Shakespeare’s theatrical text into truly effective moving pictures. All four succeed as popularizing treatments accessible to what Olivier’s collabora- tor Alan Dent called “un-Shakespeare-minded audiences.”2 They succeed as highly intelligent and original interpretations of the play capable of delight- ing any audience. Most of all, they are innovative and eloquent translations from the Elizabethan dramatic to the modern cinematic medium. It is clear that these directors have approached adapting Hamlet much as actors have long approached playing the title role, as the ultimate challenge that allows, as Almereyda observes, one’s “reflexes as a film-maker” to be “tested, battered and bettered.”3 An essential factor in the success of the films after Olivier’s is the chal- lenge of tradition. The three films that followed the groundbreaking 1948 version are what a scholar of film remakes labels “true remakes”: works that pay respectful tribute to their predecessors while laboring to surpass them.4 As each has acknowledged explicitly and as my analyses demonstrate, the three later filmmakers self-consciously defined their places in a vigorously evolving tradition of Hamlet films. -

Opera, Liberalism, and Antisemitism in Nineteenth-Century France the Politics of Halevy’S´ La Juive

Opera, Liberalism, and Antisemitism in Nineteenth-Century France The Politics of Halevy’s´ La Juive Diana R. Hallman published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru,UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, vic 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcon´ 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Diana R. Hallman 2002 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2002 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Dante MT 10.75/14 pt System LATEX 2ε [tb] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data Hallman, Diana R. Opera, liberalism, and antisemitism in nineteenth-century France: the politics of Halevy’s´ La Juive / by Diana R. Hallman. p. cm. – (Cambridge studies in opera) Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0 521 65086 0 1. Halevy,´ F., 1799–1862. Juive. 2. Opera – France – 19th century. 3. Antisemitism – France – History – 19th century. 4. Liberalism – France – History – 19th century. i. Title. ii. Series. ml410.h17 h35 2002 782.1 –dc21 2001052446 isbn 0 521 65086 0 -

Final Copy 2019 05 07 Lash

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from Explore Bristol Research, http://research-information.bristol.ac.uk Author: Lash, Dominic Title: Lost and Found Studies in Confusing Films General rights Access to the thesis is subject to the Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International Public License. A copy of this may be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This license sets out your rights and the restrictions that apply to your access to the thesis so it is important you read this before proceeding. Take down policy Some pages of this thesis may have been removed for copyright restrictions prior to having it been deposited in Explore Bristol Research. However, if you have discovered material within the thesis that you consider to be unlawful e.g. breaches of copyright (either yours or that of a third party) or any other law, including but not limited to those relating to patent, trademark, confidentiality, data protection, obscenity, defamation, libel, then please contact [email protected] and include the following information in your message: •Your contact details •Bibliographic details for the item, including a URL •An outline nature of the complaint Your claim will be investigated and, where appropriate, the item in question will be removed from public view as soon as possible. Lost and Found studies in confusing films Dominic John Alleyne Lash A dissertation submitted to the University of Bristol in accordance with the requirements for award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts Department of Film and Television December 2018 76,403 words abstract This thesis uses the concepts of disorientation and confusion as a means of providing detailed critical accounts of four difficult films, as well as of addressing some more general issues in the criticism and theory of narrative film. -

Do You Think You're What They Say You Are? Reflections on Jesus Christ Superstar

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 3 Issue 2 October 1999 Article 2 October 1999 Do You Think You're What They Say You Are? Reflections on Jesus Christ Superstar Mark Goodacre University of Birmingham, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf Recommended Citation Goodacre, Mark (1999) "Do You Think You're What They Say You Are? Reflections on Jesus Christ Superstar," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 3 : Iss. 2 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol3/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Do You Think You're What They Say You Are? Reflections on Jesus Christ Superstar Abstract Jesus Christ Superstar (dir. Norman Jewison, 1973) is a hybrid which, though influenced yb Jesus films, also transcends them. Its rock opera format and its focus on Holy Week make it congenial to the adaptation of the Gospels and its characterization of a plausible, non-stereotypical Jesus capable of change sets it apart from the traditional films and aligns it with The Last Temptation of Christ and Jesus of Montreal. It uses its depiction of Jesus as a means not of reverence but of interrogation, asking him questions by placing him in a context full of overtones of the culture of the early 1970s, English-speaking West, attempting to understand him by converting him into a pop-idol, with adoring groupies among whom Jesus struggles, out of context, in an alien culture that ultimately crushes him, crucifies him and leaves him behind. -

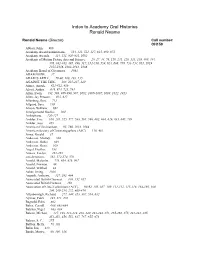

Index to Academy Oral Histories Ronald Neame

Index to Academy Oral Histories Ronald Neame Ronald Neame (Director) Call number: OH159 Abbott, John, 906 Academy Award nominations, 314, 321, 511, 517, 935, 969, 971 Academy Awards, 314, 511, 950-951, 1002 Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Science, 20, 27, 44, 76, 110, 241, 328, 333, 339, 400, 444, 476, 482-483, 495, 498, 517, 552-556, 559, 624, 686, 709, 733-734, 951, 1019, 1055-1056, 1083-1084, 1086 Academy Board of Governors, 1083 ADAM BEDE, 37 ADAM’S APPLE, 79-80, 100, 103, 135 AGAINST THE TIDE, 184, 225-227, 229 Aimee, Anouk, 611-612, 959 Alcott, Arthur, 648, 674, 725, 784 Allen, Irwin, 391, 508, 986-990, 997, 1002, 1006-1007, 1009, 1012, 1013 Allen, Jay Presson, 925, 927 Allenberg, Bert, 713 Allgood, Sara, 239 Alwyn, William, 692 Amalgamated Studios, 209 Ambiphone, 126-127 Ambler, Eric, 166, 201, 525, 577, 588, 595, 598, 602, 604, 626, 635, 645, 709 Ambler, Joss, 265 American Film Institute, 95, 766, 1019, 1084 American Society of Cinematogaphers (ASC), 118, 481 Ames, Gerald, 37 Anderson, Mickey, 366 Anderson, Robin, 893 Anderson, Rona, 929 Angel, Heather, 193 Ankers, Evelyn, 261-263 anti-Semitism, 562, 572-574, 576 Arnold, Malcolm, 773, 864, 876, 907 Arnold, Norman, 88 Arnold, Wilfred, 88 Asher, Irving, 1026 Asquith, Anthony, 127, 292, 404 Associated British Cinemas, 108, 152, 857 Associated British Pictures, 150 Association of Cine-Technicians (ACT), 90-92, 105, 107, 109, 111-112, 115-118, 164-166, 180, 200, 209-210, 272, 469-470 Attenborough, Richard, 277, 340, 353, 387, 554, 632 Aylmer, Felix, 185, 271, 278 Bagnold, Edin, 862 Baker, Carroll, 680, 883-884 Balchin, Nigel, 683, 684 Balcon, Michael, 127, 198, 212-214, 238, 240, 243-244, 251, 265-266, 275, 281-282, 285, 451-453, 456, 552, 637, 767, 855, 878 Balcon, S. -

Annual Donor Report

ANNUAL DONOR REPORT 2008 CONTENTS Letter from P. George Benson 2 President of the College of Charleston TABLE OF TABLE Letter from George P. Watt Jr. 3 Executive Vice President, Institutional Advancement Executive Director, College of Charleston Foundation TABLE OF CONTENTS By the Numbers 4 How our donors gave to the College Year at a Glance 6 Campus highlights from the 2008-2009 school year 12 1770 Society Cistern Society 14 Donors who give through their estates and other planned gifts Getting Involved visit us online: ia.cofc.edu 15 How volunteers can help make a difference 17 List of Donors Printed on acid free paper with 30% post-consumer recycled fiber. 48 Contact Us COLLEGE OF CHARLESTON ANNUAL DONOR REPORT 2008 1 TO OUR COLLEGE OF CHARLESTON COMMUNITY: lose your eyes for a moment and conjure mental images of your favorite campus settings at the College of Charleston: the Cistern Yard, Glebe CStreet, Fraternity Row on Wentworth Street, the Sottile House. … Now imagine the campus abuzz with an intellectual fervor as strong as the campus is beautiful. Imagine this energy touches every student, professor and employee at the College, and inspires every visitor. “We will become an In short, imagine the College of Charleston as a first-class national university. economic and social force Open your eyes, and you’ll see the College is nearly there: Today’s College is home to unparalleled programs in the arts, marine sciences, urban planning, on the East Coast and foster historic preservation and hospitality and tourism management, among others. It boasts signature assets that include Grice Marine Laboratory, Carolina First Arena, a healthy balance between Dixie Plantation and Addlestone Library.