Minor Rof Ssor Commit Ee Member

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Isaac Stern Gala Performance! / Beethoven Triple Concerto Mp3, Flac, Wma

Isaac Stern Gala Performance! / Beethoven Triple Concerto mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: Gala Performance! / Beethoven Triple Concerto Country: UK Released: 1965 Style: Classical MP3 version RAR size: 1416 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1698 mb WMA version RAR size: 1518 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 397 Other Formats: MP3 FLAC MIDI APE MP4 DTS MMF Tracklist Triple Concerto In C Major For Piano, Violin, Violincello And Orchestra, Op. 56 A Allegro B1 Largo B2 Rondo Alla Polacca Credits Cello – Leonard Rose Composed By – Ludwig van Beethoven Directed By – Eugene Ormandy Orchestra – Philadelphia Orchestra* Piano – Eugene Istomin Violin – Isaac Stern Barcode and Other Identifiers Label Code: D2S 320 Related Music albums to Gala Performance! / Beethoven Triple Concerto by Isaac Stern Brahms - Isaac Stern, Ormandy, Philadelphia Orchestra - Violin Concerto Beethoven, The Philadelphia Orchestra, Eugene Ormandy - Symphonie Nr. 5 Philadelphia Orchestra Conducted By Eugene Ormandy With Eugene Istomin - Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 1 In B-Flat For Piano And Orchestra, Op. 23 L. Van Beethoven : Zino Francescatti, Orchestre De Philadelphie , Direction Eugene Ormandy - Concerto En Ré Majeur Op. 61 Pour Violon Et Orchestre Isaac Stern / The Philadelphia Orchestra - Tchaikovsky: Violin Concerto In D Major / Mendelssohn: Violin Concerto In E Minor Isaac Stern With Eugene Ormandy, Philadelphia Orchestra - Conciertos Para Violon The Philadelphia Orchestra, Eugene Ormandy, Eugene Istomin - Beethoven: Concerto No. 5 "Emperor" in E Flat Major For Piano and Orchestra, Op.73 Eugene Ormandy, The Philadelphia Orchestra - Beethoven Symphony No. 3 ("Eroica") The Istomin/Stern/Rose Trio - Beethoven's Archduke Trio Isaac Stern, The Philadelphia Orchestra, Eugene Ormandy Conductor, Tchaikovsky - Mendelssohn - Violin Concerto In D Major • Violin Concerto In E Minor. -

Scott Ballantyne

present Discover The Birthday Boys Live on the Radio with Maestro George Marriner Maull Friday, May 7, 2021 8:00 PM - 10:00 PM The Birthdayy Boys Tchaikovskyik and Brahms, born onon May 7th, seven years and 2,000 miles apart, developed very different approaches to writing music. These differences will be explored by Maestro Maull and The Discovery Orchestra Quartet in this special live radio broadcast of Inside Music produced in conjunction with WWFM, The Classical Network. The producer of Inside Music is David Osenberg. The Discovery Orchestra Quartet Discovery Orchestra members violinist Rebekah Johnson, cellist Scott Ballantyne, pianist Hiroko Sasaki and violist Arturo Delmoni along with Maestro Maull will explore the fourth movement, Rondo alla Zingarese: presto from the Brahms G Minor Piano Quartet No. 1, Opus 25. Pianist Hiroko Sasaki will also share the Tchaikovsky Romance in F Minor: Andante cantabile, Opus 5. Click here for the Listening Guide. Stream from anywhere at wwfm.org or listen on 89.1 in the Trenton, NJ/Philadelphia area. Rebekah Johnson Discovery Orchestra assistant concertmaster Rebekah Johnson began violin studies in Iowa at age three and at six gave her first public performance on a CBS television special. Later that year she was awarded first prize in the Minneapolis Young Artist Competition for her performance of Mozart's Fourth Violin Concerto. After graduating high school she moved to New York City to study with Ivan Galamian and Sally Thomas receiving Bachelor and Master of Music degrees from The Juilliard School. Her chamber music coaches included Joseph Gingold, Leonard Rose, Felix Galimir and the Juilliard Quartet. -

Diran Alexanian: Complete Cello Technique: Classic Treatise on Cello Theory and Practice Pdf

FREE DIRAN ALEXANIAN: COMPLETE CELLO TECHNIQUE: CLASSIC TREATISE ON CELLO THEORY AND PRACTICE PDF Diran Alexanian,David Geber,Pablo Casals | 224 pages | 10 Apr 2003 | Dover Publications Inc. | 9780486426600 | English | New York, United States Alexanian, Diran - COMPLETE CELLO TECHNIQUE: THE CLASSIC TREATISE ON CELLO THEORY AND PRACTICE Reprinted from the original dual-language edition French and English instruction side-by-side on the pagewith numerous photographs, diagrams, and music examples, it is a superb compendium of instruction for student and growing professional alike. Alexanian--who played chamber music with Brahms, performed concertos with Mahler, taught alongside Casals in Paris, and saw his influential ideas shape the careers of such cellists as the legendary Gregor Piatigorsky--received the highest praise of Casals in his preface: ". Unabridged republication of the work originally published by A. Zunz Mathot, Paris, By Stephen J. Benham, Mary L. Evans, D By Ivan Galamian and Sally Thomas. By Dimitry Markevitch, Diran Alexanian: Complete Cello Technique: Classic Treatise on Cello Theory and Practice by Florence W. Books by Walter Gieseking and Karl Leimer. Join Our Email List. We use cookies to analyze site usage, enhance site usability, and assist in our marketing efforts. Your Orders. Your Lists. Product Details. Additional Information. You May Also Like. Frederick H. Added to cart. Email me when this product is available. Email Address. Notify Me. Thank You. We'll notify you when this product is available. Continue Shopping. Do you already have a SmartMusic subscription? Yes, open this title in SmartMusic. No, show me a free preview title. Create New List. Added to. -

The Search for Consistent Intonation: an Exploration and Guide for Violoncellists

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2017 THE SEARCH FOR CONSISTENT INTONATION: AN EXPLORATION AND GUIDE FOR VIOLONCELLISTS Daniel Hoppe University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2017.380 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Hoppe, Daniel, "THE SEARCH FOR CONSISTENT INTONATION: AN EXPLORATION AND GUIDE FOR VIOLONCELLISTS" (2017). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 98. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/98 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies. -

AN IMPORTANT NOTE from Johnstone-Music ABOUT THE

AN IMPORTANT NOTE FROM Johnstone-Music ABOUT THE MAIN ARTICLE STARTING ON THE FOLLOWING PAGE: We are very pleased for you to have a copy of this article, which you may read, print or save on your computer. You are free to make any number of additional photocopies, for johnstone-music seeks no direct financial gain whatsoever from these articles; however, the name of THE AUTHOR must be clearly attributed if any document is re-produced. If you feel like sending any (hopefully favourable) comment about this, or indeed about the Johnstone-Music web in general, simply visit the ‘Contact’ section of the site and leave a message with the details - we will be delighted to hear from you ! Leonard Rose: America’s Golden Age and Its First Cellist Steven Honigberg A Book Review by Jayne I. Hanlin Johnstone-Music is honoured to have the collaboration of Jayne Hanlin Leonard Rose: America’s Golden Age and Its First Cellist Steven Honigberg A Book Review by Jayne I. Hanlin Steven Honigberg, a student of Leonard Rose, has written the first biography of one of the world‟s greatest cellists: Leonard Rose: America’s Golden Age and Its First Cellist. Anyone who purchases the book may request a free bonus CD of Rose performing two cello concerti never released commercially: Alan Shulman‟s Concerto for Violoncello and Orchestra (1948) and Peter Mennin‟s Cello Concerto (1956). Quite an amazing offer. Divided into 25 chapters, this 501-page volume contains eight appendices, which include details about performances in Rose‟s symphonic and chamber music career as well as solo appearances* with major orchestras, his discography, and several musical review fragments. -

Eugene Ormandy Commercial Sound Recordings Ms

Eugene Ormandy commercial sound recordings Ms. Coll. 410 Last updated on October 31, 2018. University of Pennsylvania, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts 2018 October 31 Eugene Ormandy commercial sound recordings Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History..........................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 5 Related Materials........................................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................6 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 7 - Page 2 - Eugene Ormandy commercial sound recordings Summary Information Repository University of Pennsylvania: Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts Creator Ormandy, Eugene, 1899-1985 -

A Great Wave in the Evolution of the Modern Cellist: Diran Alexanian and Maurice Eisenberg, Two Master Cello Pedagogues from the Legacy of Pablo Casals

A GREAT WAVE IN THE EVOLUTION OF THE MODERN CELLIST: DIRAN ALEXANIAN AND MAURICE EISENBERG, TWO MASTER CELLO PEDAGOGUES FROM THE LEGACY OF PABLO CASALS by Oskar Falta B.Mus., Robert Schumann Hochschule, 2014 M.Mus., Royal Academy of Music, 2016 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Orchestral Instrument) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) November 2019 © Oskar Falta, 2019 The following individuals certify that they have read, and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies for acceptance, the dissertation entitled: A Great Wave in the Evolution of the Modern Cellist: Diran Alexanian and Maurice Eisenberg, Two Master Cello Pedagogues from the Legacy of Pablo Casals submitted by Oskar Falta in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Orchestral Instrument Examining Committee: Eric Wilson, Music Co-supervisor Claudio Vellutini, Music Co-supervisor Michael Zeitlin, English Languages and Literatures University Examiner Corey Hamm, Music University Examiner Jasper Wood, Music Supervisory Committee Member ii Abstract Pablo Casals (1876-1973) ranks amongst the most influential figures in the history of the violoncello. Casals never held a permanent teaching position, neither did he commit his teaching philosophy to paper. This thesis examines three selected aspects of expressive tools: intonation, vibrato, and portamento – as interpreted by Casals – and defines how they are reflected in methods of two cellists with first-hand access to Casals's knowledge: Diran Alexanian (1881-1954) and Maurice Eisenberg (1900-1972). The first chapter presents two extensive biographical accounts of these authors. -

Download Diran Alexanian: Complete Cello Technique: Classic

DIRAN ALEXANIAN: COMPLETE CELLO TECHNIQUE: CLASSIC TREATISE ON CELLO THEORY AND PRACTICE DOWNLOAD FREE BOOK Diran Alexanian, David Geber, Pablo Casals | 224 pages | 10 Apr 2003 | Dover Publications Inc. | 9780486426600 | English | New York, United States DOVER DIRAN ALEXANIAN COMPLETE CELLO TECHNIQUE - CELLO Regardless of size, each musical unit — be it a single note, note grouping or a larger phrase — requires a unique kind of vibrato. You can't do all those Diran Alexanian: Complete Cello Technique: Classic Treatise on Cello Theory and Practice and have a different ideal of intonation. Greenhouse remembers that Alexanian's bow arm was stiff and his skills as a player doubtful: "He never touched the cello during lessons, except to show an occasional fingering or something. Expression Through Intonation Upon hearing Casals for the first time, a participant of his classes at the University of California Berkeley once reportedly exclaimed: "It is soooooo beautiful — but why does he play out of tune? By some, such practice was regarded as tasteless: … there were those who were described as playing in an overly sentimental 'salon style. The violinist Carl Flesch speaks of three basic methods of employing the 24portamento: "An uninterrupted slide on one finger … A slide in which one finger slides from the starting note to an intermediate note, and a second finger stops the destination note" and "A slide in which one finger plays the starting note, and a second finger stops an intermediate note and slides to the destination note. Mantel, Gerhard. The oscillation should originate in the elbow and end in the fingertip, moving from side to side in a motion parallel to the string. -

Cabrillo Festival of Contemporarymusic of Contemporarymusic Marin Alsop Music Director |Conductor Marin Alsop Music Director |Conductor 2015

CABRILLO FESTIVAL OFOF CONTEMPORARYCONTEMPORARY MUSICMUSIC 2015 MARINMARIN ALSOPALSOP MUSICMUSIC DIRECTOR DIRECTOR | | CONDUCTOR CONDUCTOR SANTA CRUZ CIVIC AUDITORIUM CRUZ CIVIC AUDITORIUM SANTA BAUTISTA MISSION SAN JUAN PROGRAM GUIDE art for all OPEN<STUDIOS ART TOUR 2015 “when i came i didn’t even feel like i was capable of learning. i have learned so much here at HGP about farming and our food systems and about living a productive life.” First 3 Weekends – Mary Cherry, PrograM graduate in October Chances are you have heard our name, but what exactly is the Homeless Garden Project? on our natural Bridges organic 300 Artists farm, we provide job training, transitional employment and support services to people who are homeless. we invite you to stop by and see our beautiful farm. You can Good Times pick up some tools and garden along with us on volunteer + September 30th Issue days or come pick and buy delicious, organically grown vegetables, fruits, herbs and flowers. = FREE Artist Guide Good for the community. Good for you. share the love. homelessgardenproject.org | 831-426-3609 Visit our Downtown Gift store! artscouncilsc.org unique, Local, organic and Handmade Gifts 831.475.9600 oPen: fridays & saturdays 12-7pm, sundays 12-6 pm Cooper House Breezeway ft 110 Cooper/Pacific Ave, ste 100G AC_CF_2015_FP_ad_4C_v2.indd 1 6/26/15 2:11 PM CABRILLO FESTIVAL OF CONTEMPORARY MUSIC SANTA CRUZ, CA AUGUST 2-16, 2015 PROGRAM BOOK C ONTENT S For information contact: www.cabrillomusic.org 3 Calendar of Events 831.426.6966 Cabrillo Festival of Contemporary -

4 0 T H Anniversary Celebration

40TH A NNIVERSA R Y CELEBRATION MAY 10, 11 & 12, 2013 DeBartolo Performing Arts Center University of Notre Dame Fortieth Annual National Chamber Music Competition AMERICA’S PREMIER EDUCATIONAL CHAMBER MUSIC COMPETITION Welcome to the Fischoff Elected Officials Letters .......................................................2-3 President and Artistic Director Letters .................................... 4 Board of Directors ................................................................... 5 Welcome to Notre Dame Letter from Father Jenkins ....................................................... 6 Campus Map ........................................................................... 7 The Fischoff National Chamber Music Association History, Mission and Financial Retrospective ......................... 8 Staff and Competition Staff .................................................... 9 National Advisory Council ..............................................10-11 Residency Program...........................................................12-13 Double Gold Tours ..........................................................14-15 Musician-of-the-Month ........................................................ 16 Chamber Music Mentoring Project ..................................... 17 Peer Ambassadors for Chamber Music (PACMan) .............. 19 The 40th Annual Fischoff Competition History of the Competition .................................................. 21 History of Fischoff Winners .............................................22-23 Geoffroy -

Steven Honigberg – Biography

Cello Jack Price Managing Director 1 (310) 254-7149 Skype: pricerubin [email protected] Rebecca Petersen Executive Administrator 1 (916) 539-0266 Skype: rebeccajoylove [email protected] Olivia Stanford Marketing Operations Manager [email protected] Contents: Karrah O’Daniel-Cambry Biography Opera and Marketing Manager [email protected] Leonard Rose Biography Press Mailing Address: Discography 1000 South Denver Avenue Repertoire Suite 2104 Recent Event Tulsa, OK 74119 YouTube Video Links Website: Photo Gallery http://www.pricerubin.com Complete artist information including video, audio and interviews are available at www.pricerubin.com Steven Honigberg – Biography Steven Honigberg is a graduate of the Juilliard School of Music where he studied with Leonard Rose and Channing Robbins. Hired under the leadership of Mstislav Rostropovich, he is currently a member of the National Symphony Orchestra. Mr. Honigberg has given recent recitals in Washington DC at the Dumbarton Concert Series, at the Phillips Collection, at the National Gallery of Art, and recitals in New York and throughout the United States. In Chicago (his home town) he has appeared on radio WFMT, at the Ravinia Festival, and as soloist with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Ars Viva Orchestra, Lake Forest Symphony and New Philharmonic Orchestra among others. In October 2014 Honigberg performed Andrzej Panufnik’s Cello Concerto with conductor Marek Mos in Warsaw, Poland. He has appeared most recently in Washington, in 2015, as soloist with the National Symphony Orchestra in two performances at the Kennedy Center of Krzysztof Penderecki’s Triple Cello Concerto with the NSO’s Music Director Christoph Eschenbach. In 2009 Mr. Honigberg performed Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s Cello Concerto with the NSO and won rave reviews for the 1988 world premiere of David Ott’s Concerto for Two Cellos conducted by Mstislav Rostropovich and the National Symphony with repeat performances on two NSO United States tours. -

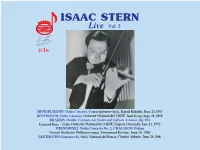

ISAAC STERN D O I Live Vol

R E M ISAAC STERN D O I Vol. 5 Live 2CDs MENDELSSOHN: Violin Concerto, Concertgebouw Orch., Rafael Kubelik, June 21, 1951 BEETHOVEN: Violin Concerto, Orchestre National de l’ORTF, Josef Krips, Sept. 18, 1958 BRAHMS: Double Concerto for Violin and Cello in A minor, Op. 102 Leonard Rose - Cello, Orchestre National de l’ORTF, Eugene Ormandy, Jan. 21, 1972 WIENIAWSKI: Violin Concerto No. 2; CHAUSSON: Poème Nouvel Orchestre Philharmonique, Emmanuel Krivine. June 14, 1980 BEETHOVEN: Romance #2, Orch. National de France, Claudio Abbado, June 28, 1960 - - CD1 - - BEETHOVEN: Violin concerto in D major, Op. 61 41:38 1. I. Allegro ma non troppo 23:12 2. II. Larghetto 9:24 3. III. Rondo: Allegro 8:56 Orchestre National de l’ORTF, Josef Krips - conductor Live performance, September 18, 1958 BRAHMS: Double Concerto for Violin & Cello in A minor, Op. 102 32:49 4. I: Allegro 16:21 5. II: Andante 7:18 6. III: Vivace non troppo 9:08 Leonard Rose - Cello Orchestre National de l’ORTF, Eugene Ormandy - conductor Live performance, Paris, January 21, 1972 - - CD2 - - MENDELSSOHN: Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. 64 26:36 1. I. Allegro molto appassionato 11:55 2. II. Andante 8:25 3. III. Allegretto non troppo - Allegro molto vivace 6:10 Concertgebouw Orchestra, Rafael Kubelik - conductor Live performance, June 21, 1951 WIENIAWSKI: Violin Concerto No. 2 in D minor, Op. 22 22:42 4. I. Allegro moderato 11:35 5. II. Romance: Andante non troppo 4:36 6. III. Allegro con fuoco 6:28 7. CHAUSSON: Poème for Violin and Orchestra, Op.