Talking About the Weather: Climate and the Victorian Novel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Education Forum

The newsletter for the Education Section of the BSHS No 42 Education February 2004 Forum Edited by Martin Monk 32, Rainville Road, Hammersmith, London W6 9HA Tel: 0207-385-5633. e-mail: [email protected] Contents Editorial 1 Articles - Poems of science: Chaucer’s doctor of physic 1 - Deadening uniformity or liberated pluralism: 5 can we learn from the past? - A tale of two teachers? 8 News Items 12 Forthcoming Events 14 Reviews - Great Physicists: the life and times of leading physicists from Galileo to Hawking 15 - Mercator: the man who mapped the planet 17 - The Lunar Men: the friends who made the future 19 - Gods in the Sky: Astronomy from the ancients to the Renaissance 21 Resources - Wright Brothers and flight 22 - Darwin and Design 22 - How to Win The Nobel Prize 22 - 1 - Editorial Martin Monk I have been helping Kate Buss with the editing for the past year. Now she has asked me to take over. I wish to thank Kate for more than four years of patience and skill in editing Education Forum. I think we all wish her well in the future. So this is the first issue of Education Forum for which I take sole responsibility Tuesday 4th May is the deadline for copy for the next issue of Education Forum. [email protected] Articles Poems of science John Cartwright In this new series John Cartwright takes a poem each issue of Forum and examines its scientific content. With last year’s BBC screening of an updated version of the Canterbury Tales there is more than one reason to start with Chaucer. -

The Lunar Society of Birmingham and the Practice of Science in 18Th Century Great Britain

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2011 The unL ar Society of Birmingham and the Practice of Science in 18th Century Great Britain Scott H. Zurawel Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons Recommended Citation Zurawel, Scott H., "The unL ar Society of Birmingham and the Practice of Science in 18th Century Great Britain" (2011). Honors Theses. 1092. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/1092 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i THE LUNAR SOCIETY OF BIRMINGHAM AND THE PRACTICE OF SCIENCE IN 18TH CENTURY GREAT BRITAIN: A STUDY OF JOSPEH PRIESTLEY, JAMES WATT AND WILLIAM WITHERING By Scott Henry Zurawel ******* Submitted in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for Honors in the Department of History UNION COLLEGE March, 2011 ii ABSTRACT Zurawel, Scott The Lunar Society of Birmingham and the Practice of Science in Eighteenth-Century Great Britain: A Study of Joseph Priestley, James Watt, and William Withering This thesis examines the scientific and technological advancements facilitated by members of the Lunar Society of Birmingham in eighteenth-century Britain. The study relies on a number of primary sources, which range from the regular correspondence of its members to their various published scientific works. The secondary sources used for this project range from comprehensive books about the society as a whole to sources concentrating on particular members. -

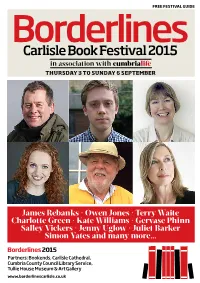

Borderlines 2015

FREE FESTIVAL GUIDE BorderlinesCarlisle Book Festival 2015 in association with cumbrialife THURSDAY 3 TO SUNDAY 6 SEPTEMBER James Rebanks � Owen Jones � Terry Waite Charlotte Green � Kate Williams � Gervase Phinn Salley Vickers � Jenny Uglow � Juliet Barker Simon Yates and many more... Borderlines 2015 Partners: Bookends, Carlisle Cathedral, Cumbria County Council Library Service, Tullie House Museum & Art Gallery www.borderlinescarlisle.co.uk President’s welcome city strolling Rigby Phil Photography The Lanes Carlisle ell done to everyone at The growth in literary festivals in the last image courtesy of BHS Borderlines for making it decade has partly been because the such a resounding reading public, in fact the general public, success, for creating a do like to hear and see real live people for Wliterary festival and making it well and a change, instead of staring at some sort truly a part of the local community, nay, of inanimate box or computer contrap- part of national literary life. It is now so tion. The thing about Borderlines is that well established and embedded that it it is totally locally created and run, a feels as if it has been going for ever, not- for- profit event, from which no one though in fact it only began last year… gets paid. There is a committee of nine yes, only one year ago, so not much to who include representatives from boast about really, but existing- that is an Cumbria County Council, Bookends, achievement in itself. There are now Tullie House and the Cathedral. around 500 annual literary festivals in So keep up the great work. -

FNL Annual Report 2018

Friends of the National Libraries 1 CONTENTS Administrative Information 2 Annual Report for 2018 4 Acquisitions by Gift and Purchase 10 Grants for Digitisation and Open Access 100 Address by Lord Egremont 106 Trustees’ Report 116 Financial Statements 132 2 Friends of the National Libraries Administrative Information Friends of the National Libraries PO Box 4291, Reading, Berkshire RG8 9JA Founded 1931 | Registered Charity Number: 313020 www.friendsofnationallibraries.org.uk [email protected] Royal Patron: HRH The Prince of Wales Chairman of Trustees: to June 28th 2018: The Lord Egremont, DL, FSA, FRSL from June 28th 2018: Mr Geordie Greig Honorary Treasurer and Trustee: Mr Charles Sebag-Montefiore, FSA, FCA Honorary Secretary: Dr Frances Harris, FSA, FRHistS (to June 28th 2018) Membership Accountant: Mr Paul Celerier, FCA Secretary: Mrs Nell Hoare, MBE FSA (from June 28th 2018) Administrative Information 3 Trustees Scottish Representative Dr Iain Brown, FSA, FRSE Ex-officio Dr Jessica Gardner General Council University Librarian, University of Cambridge Mr Philip Ziegler, CVO Dr Kristian Jensen, FSA Sir Tom Stoppard, OM, CBE Head of Arts and Humanities, British Library Ms Isobel Hunter Independent Auditors Secretary, Historical Manuscripts Commission Knox Cropper, 65 Leadenhall Street, London EC3A 2AD (to 28th February 2018) Roland Keating Investment Advisers Chief Executive, British Library Cazenove Capital Management Dr Richard Ovenden London Wall Place, London EC2Y 5AU Bodley’s Librarian, Bodleian Libraries Dr John Scally Principal -

Mickey WIS 2009 England Registration Brochure 2.Pub

HHHEELLLLOOELLO E NNGGLLANANDDNGLAND, WWWEEE’’’RREERE B ACACKKACK!!! JJuunneeJune 888-8---14,1144,,14, 220000992009 WWISISWIS ### 554454 Wedgwood Museum Barlaston, England Celebrating 250 Years At Wedgwood, The 200th Birthday Of Charles Darwin And The New Wedgwood Museum 2009 marks the 250th anniversary of the founding of The Wedgwood Company. 2009 also marks the 200th anniversary of the birth of Charles Darwin and the 150th anniversary of the publication of his book, ‘On The Origin Of Species’. The great 19th Century naturalist had many links with Staffordshire, the Wedgwood Family, and there are many events being held there this year. The Wedgwood International Seminar is proud to hold it’s 54th Annual Seminar at the New Wedgwood Museum this year and would like to acknowledge the time and efforts put forth on our behalf by the Wedgwood Museum staff and in particular Mrs. Lynn Miller. WIS PROGRAM - WIS #54, June 8-14 - England * Monday - June 8, 2009 9:00 AM Bus Departs London Hotel To Moat House Hotel Stoke-On-Trent / Lunch On Your Own 3:00 PM Registration 3:00 PM, Moat House Hotel 5:30 PM Bus To Wedgwood Museum 6:00 PM President’s Reception @Wedgwood Museum-Meet Senior Members of the Company Including Museum Trustees, Museum Staff, Volunteers 7:00 PM Dinner & After Dinner Announcements Tuesday - June 9, 2009 8:45 AM Welcome: Earl Buckman, WIS President, George Stonier, President of the Museum, Gaye Blake Roberts, Museum Director 9:30 AM Kathy Niblet, Formerly of the Potteries Museum & Art Gallery “Studio Potters” 10:15 AM Lord Queesnberry -

1 THOMPSON SQUARE Are You Gonna Kiss Me Or Not Stoney

TOP100 OF 2011 1 THOMPSON SQUARE Are You Gonna Kiss Me Or Not Stoney Creek 51 BRAD PAISLEY Anything Like Me Arista 2 JASON ALDEAN & KELLY CLARKSON Don't You Wanna Stay Broken Bow 52 RONNIE DUNN Bleed Red Arista 3 TIM MCGRAW Felt Good On My Lips Curb 53 THOMPSON SQUARE I Got You Stoney Creek 4 BILLY CURRINGTON Let Me Down Easy Mercury 54 CARRIE UNDERWOOD Mama's Song 19/Arista 5 KENNY CHESNEY Somewhere With You BNA 55 SUNNY SWEENEY From A Table Away Republic Nashville 6 SARA EVANS A Little Bit Stronger RCA 56 ERIC CHURCH Homeboy EMI Nashville 7 BLAKE SHELTON Honey Bee Warner Bros./WMN 57 TAYLOR SWIFT Sparks Fly Big Machine 8 THE BAND PERRY You Lie Republic Nashville 58 BILLY CURRINGTON Love Done Gone Mercury 9 MIRANDA LAMBERT Heart Like Mine Columbia 59 DAVID NAIL Let It Rain MCA 10 CHRIS YOUNG Voices RCA 60 MIRANDA LAMBERT Baggage Claim RCA 11 DARIUS RUCKER This Capitol 61 STEVE HOLY Love Don't Run Curb 12 LUKE BRYAN Someone Else Calling... Capitol 62 GEORGE STRAIT The Breath You Take MCA 13 CHRIS YOUNG Tomorrow RCA 63 EASTON CORBIN I Can't Love You Back Mercury 14 JASON ALDEAN Dirt Road Anthem Broken Bow 64 JERROD NIEMANN One More Drinkin' Song Sea Gayle/Arista 15 JAKE OWEN Barefoot Blue Jean Night RCA 65 SUGARLAND Little Miss Mercury 16 JERROD NIEMANN What Do You Want Sea Gayle/Arista 66 JOSH TURNER I Wouldn't Be A Man MCA 17 BLAKE SHELTON Who Are You When I'm.. -

View Song List

Song Artist What's Up 4 Non Blondes You Shook Me All Night Long AC-DC Song of the South Alabama Mountain Music Alabama Piano Man Billy Joel Austin Blake Shelton Like a Rolling Stone Bob Dylan Boots of Spanish Leather Bob Dylan Summer of '69 Bryan Adams Tennessee Whiskey Chris Stapleton Mr. Jones Counting Crows Ants Marching Dave Matthews Dust on the Bottle David Lee Murphy The General Dispatch Drift Away Dobie Gray American Pie Don McClain Castle on the Hill Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud Ed Sheeran Rocket Man Elton John Tiny Dancer Elton John Your Song Elton John Drink In My Hand Eric Church Give Me Back My Hometown Eric Church Springsteen Eric Church Like a Wrecking Ball Eric Church Record Year Eric Church Wonderful Tonight Eric Clapton Rock & Roll Eric Hutchinson OK It's Alright With Me Eric Hutchinson Cruise Florida Georgia Line Friends in Low Places Garth Brooks Thunder Rolls Garth Brooks The Dance Garth Brooks Every Storm Runs Out Gary Allan Hey Jealousy Gin Blossoms Slide Goo Goo Dolls Friend of the Devil Grateful Dead Let Her Cry Hootie and the Blowfish Bubble Toes Jack Johnson Flake Jack Johnson Barefoot Bluejean Night Jake Owen Carolina On My Mind James Taylor Fire and Rain James Taylor I Won't Give Up Jason Mraz Margaritaville Jimmy Buffett Leaving on a Jet Plane John Denver All of Me John Legend Jack & Diane John Mellancamp Folsom Prison Blues Johnny Cash Don't Stop Believing Journey Faithfully Journey Walking in Memphis Marc Cohn Sex and Candy Marcy's Playground 3am Matchbox 20 Unwell Matchbox 20 Bright Lights Matchbox 20 You Took The Words Right Out Of Meatloaf All About That Bass Megan Trainor Man In the Mirror Michael Jackson To Be With You Mr. -

Curriculum Vitae (Updated August 1, 2021)

DAVID A. BELL SIDNEY AND RUTH LAPIDUS PROFESSOR IN THE ERA OF NORTH ATLANTIC REVOLUTIONS PRINCETON UNIVERSITY Curriculum Vitae (updated August 1, 2021) Department of History Phone: (609) 258-4159 129 Dickinson Hall [email protected] Princeton University www.davidavrombell.com Princeton, NJ 08544-1017 @DavidAvromBell EMPLOYMENT Princeton University, Director, Shelby Cullom Davis Center for Historical Studies (2020-24). Princeton University, Sidney and Ruth Lapidus Professor in the Era of North Atlantic Revolutions, Department of History (2010- ). Associated appointment in the Department of French and Italian. Johns Hopkins University, Dean of Faculty, School of Arts & Sciences (2007-10). Responsibilities included: Oversight of faculty hiring, promotion, and other employment matters; initiatives related to faculty development, and to teaching and research in the humanities and social sciences; chairing a university-wide working group for the Johns Hopkins 2008 Strategic Plan. Johns Hopkins University, Andrew W. Mellon Professor in the Humanities (2005-10). Principal appointment in Department of History, with joint appointment in German and Romance Languages and Literatures. Johns Hopkins University. Professor of History (2000-5). Johns Hopkins University. Associate Professor of History (1996-2000). Yale University. Assistant Professor of History (1991-96). Yale University. Lecturer in History (1990-91). The New Republic (Washington, DC). Magazine reporter (1984-85). VISITING POSITIONS École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, Visiting Professor (June, 2018) Tokyo University, Visiting Fellow (June, 2017). École Normale Supérieure (Paris), Visiting Professor (March, 2005). David A. Bell, page 1 EDUCATION Princeton University. Ph.D. in History, 1991. Thesis advisor: Prof. Robert Darnton. Thesis title: "Lawyers and Politics in Eighteenth-Century Paris (1700-1790)." Princeton University. -

In the Polite Eighteenth Century, 1750–1806 A

AMERICAN SCIENCE AND THE PURSUIT OF “USEFUL KNOWLEDGE” IN THE POLITE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY, 1750–1806 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Notre Dame in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Elizabeth E. Webster Christopher Hamlin, Director Graduate Program in History and Philosophy of Science Notre Dame, Indiana April 2010 © Copyright 2010 Elizabeth E. Webster AMERICAN SCIENCE AND THE PURSUIT OF “USEFUL KNOWLEDGE” IN THE POLITE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY, 1750–1806 Abstract by Elizabeth E. Webster In this thesis, I will examine the promotion of science, or “useful knowledge,” in the polite eighteenth century. Historians of England and America have identified the concept of “politeness” as a key component for understanding eighteenth-century culture. At the same time, the term “useful knowledge” is also acknowledged to be a central concept for understanding the development of the early American scientific community. My dissertation looks at how these two ideas, “useful knowledge” and “polite character,” informed each other. I explore the way Americans promoted “useful knowledge” in the formative years between 1775 and 1806 by drawing on and rejecting certain aspects of the ideal of politeness. Particularly, I explore the writings of three central figures in the early years of the American Philosophical Society, David Rittenhouse, Charles Willson Peale, and Benjamin Rush, to see how they variously used the language and ideals of politeness to argue for the promotion of useful knowledge in America. Then I turn to a New Englander, Thomas Green Fessenden, who identified and caricatured a certain type of man of science and satirized the late-eighteenth-century culture of useful knowledge. -

Request List 619 Songs 01012021

PAT OWENS 3 Doors Down Bill Withers Brothers Osbourne (cont.) Counting Crows Dierks Bentley (cont.) Elvis Presley (cont.) Garth Brooks (cont.) Hank Williams, Jr. Be Like That Ain't No Sunshine Stay A Little Longer Accidentally In Love I Hold On Can't Help Falling In Love Standing Outside the Fire A Country Boy Can Survive Here Without You Big Yellow Taxi Sideways Jailhouse Rock That Summer Family Tradition Kryptonite Billy Currington Bruce Springsteen Long December What Was I Thinking Little Sister To Make You Feel My Love Good Directions Glory Days Mr. Jones Suspicious Minds Two Of A Kind Harry Chapin 4 Non Blondes Must Be Doin' Somethin' Right Rain King Dion That's All Right (Mama) Two Pina Coladas Cat's In The Cradle What's Up (What’s Going On) People Are Crazy Bryan Adams Round Here Runaround Sue Unanswered Prayers Pretty Good At Drinking Beer Heaven Eric Church Hinder 7 Mary 3 Summer of '69 Craig Morgan Dishwalla Drink In My Hand Gary Allan Lips Of An Angel Cumbersome Billy Idol Redneck Yacht Club Counting Blue Cars Jack Daniels Best I Ever Had Rebel Yell Buckcherry That's What I Love About Sundays Round Here Buzz Right Where I Need To Be Hootie and the Blowfish Aaron Lewis Crazy Bitch This Ole Boy The Divinyls Springsteen Smoke Rings In The Dark Hold My Hand Country Boy Billy Joel I Touch Myself Talladega Watching Airplanes Let Her Cry Only The Good Die Young Buffalo Springfield Creed Only Wanna Be With You AC/DC Piano Man For What It's Worth My Sacrifice Dixie Chicks Eric Clapton George Jones Time Shook Me All Night Still Rock And -

Box Office 0870 343 1001 the Radcliffe Camera, the Bodleian Library

Sunday 29 March – Sunday 5 April 2009 at Christ Church, Oxford Featuring Mario Vargas Llosa Ian McEwan Vince Cable Simon Schama P D James John Sentamu Robert Harris Joan Bakewell David Starkey Richard Holmes A S Byatt John Humphrys Philip Pullman Michael Holroyd Joanne Harris Jeremy Paxman Box Office 0870 343 1001 www.sundaytimes-oxfordliteraryfestival.co.uk The Radcliffe Camera, The Bodleian Library. The Library is a major new partner of the Festival. WELCOME Welcome We are delighted to welcome you to the 2009 Sunday Particular thanks this year to our partners at Times Oxford Literary Festival - our biggest yet, The Sunday Times for their tremendous coverage spread over eight days with more than 430 speakers. and support of the Festival, and to all our very We have an unprecedented and stimulating series generous sponsors, donors and supporters, of prestige events in the magnificent surroundings especially our friends at Cox and Kings Travel. of Christ Church, the Sheldonian Theatre and We have enlarged and enhanced public facilities Bodleian Library. But much also to amuse and divert. in the marquees at Christ Church Meadow and in the Master’s Garden, which we hope you will Ticket prices have been held to 2008 levels, offering enjoy. We are very grateful to the Dean, the outstanding value for money, so that everyone Governing Body and the staff at Christ Church for can enjoy a host of national and international their help and support. speakers, talking, conversing and debating throughout the week on every conceivable topic. Hitherto, the Festival has been a ‘Not for Profit’ Company, but during 2009 we will move to establish The Sunday Times Oxford Festival is dedicated a new Charitable Trust. -

Popular Wedding Covers (346)

The Atlanta Wedding Band is proud to have performed over 100 weddings since the beginning of 2011. We have the distinct honor of being a 5 star band on www.gigmasters.com, not only that, but every client that has booked us through that site has given us 5 out of 5! Atlanta Wedding Band 1418 Dresden Drive Unit 365, Atlanta, Georgia, 30319, United States. 404-272-0337 Popular Wedding Covers (346) For an all inclusive list (700+), scroll further down! Motown/R&B/Funk/Dance (53) Al Green Let’s Stay Together Aretha Franklin Ain’t No Mountain High Enough BeeGees Stayin Alive Ben E. King Stand by Me Beyonce Knowles Irreplaceable Bill Withers Ain’t No Sunshine Lean On Me Black Eyed Peas I Got a Feeling Bruno Mars (Mark Ronson) Marry You Uptown Funk Cee-Lo Green Forget You Chubby Checker The Twist The Commodores Brick House The Contours Do You Love Me Cupid Cupid Shuffle Dexy’s Midnight Runners Come on Eileen Earth Wind and Fire September The Foundations Build me Up Buttercup The Four Tops I Can’t Help Myself (Sugar pie, Honey Bunch) Hall and Oates You Make My Dreams The Isley Brothers Shout Jackson 5 ABC I Want You Back James Brown I Feel Good Jason Derulo It Girl Want to Want Me Kenny Loggins Footloose King Harvest Dancing in the Moonlight Kool and the Gang Celebration Lionel Ritchie All Night Long Louis Armstrong What a Wonderful World Marvin Gaye How Sweet It Is Let’s Get it On Sexual Healing Michael Jackson Billie Jean Man in the Mirror Otis Redding Sittin on the Dock of the Bay Outkast Hey Ya Sorry Ms.