He Ffecti E Rt of O El Ntelligent N Iron Ents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BRBL 2016-2017 Annual Report.Pdf

BEINECKE ILLUMINATED No. 3, 2016–17 Annual Report Cover: Yale undergraduate ensemble Low Strung welcomed guests to a reception celebrating the Beinecke’s reopening. contributorS The Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library acknowledges the following for their assistance in creating and compiling the content in this annual report. Articles written by, or adapted from, Phoenix Alexander, Matthew Beacom, Mike Cummings, Michael Morand, and Eve Neiger, with editorial guidance from Lesley Baier Statistics compiled by Matthew Beacom, Moira Fitzgerald, Sandra Stein, and the staff of Technical Services, Access Services, and Administration Photographs by the Beinecke Digital Studio, Tyler Flynn Dorholt, Carl Kaufman, Mariah Kreutter, Mara Lavitt, Lotta Studios, Michael Marsland, Michael Morand, and Alex Zhang Design by Rebecca Martz, Office of the University Printer Copyright ©2018 by Yale University facebook.com/beinecke @beineckelibrary twitter.com/BeineckeLibrary beinecke.library.yale.edu SubScribe to library newS messages.yale.edu/subscribe 3 BEINECKE ILLUMINATED No. 3, 2016–17 Annual Report 4 From the Director 5 Beinecke Reopens Prepared for the Future Recent Acquisitions Highlighted Depth and Breadth of Beinecke Collections Destined to Be Known: African American Arts and Letters Celebrated on 75th Anniversary of James Weldon Johnson Collection Gather Out of Star-Dust Showcased Harlem Renaissance Creators Happiness Exhibited Gardens in the Archives, with Bird-Watching Nearby 10 344 Winchester Avenue and Technical Services Two Years into Technical -

Beinecke Illuminated, No. 6, 2019–20 Annual Report

BEINECKE ILLUMINATED No. 6, 2019–20 Annual Report Front cover: Photograph of the scultpure garden by Iwan Baan. Back cover: Dr. Walter Evans, Melissa Barton, and Edwin C. Schroeder reviewing the Walter O. Evans Collection of Frederick Douglass and Douglass Family Papers. Contributors The Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library acknowledges the following for their assistance in creating and compiling the content in this annual report. Articles written by, or adapted from, Michael Morand and Michael Cummings, with editorial assistance from David Baker, Bianca Ibarlucea, and Eva Knaggs. Statistics compiled by Ellen Doon, Moira Fitzgerald, Eric Friede, Michael Morand, Audrey Pearson, Allison Van Rhee, and the staff of Technical Services, Access Services, and Administration. Photographs of Beinecke Library events, exhibitions, and materials by Tubyez Cropper, Dante Haughton, and Michael Morand; Windham-Campbell Prize image from YaleNews; Georgia O’Keeffe manuscript images courtesy of Sotheby’s; Wayne Koestenbaum photo by Tim Schutsky; photograph of Matthew Dudley and Ozgen Felek by Michael Helfenbein. Design by Rebecca Martz, Office of the University Printer. Copyright ©2020 by Yale University facebook.com/beinecke @beineckelibrary twitter.com/BeineckeLibrary beinecke.library.yale.edu subsCribe to library news subscribe.yale.edu BEINECKE ILLUMINATED No. 6, 2019–20 Annual Report 4 From the Director 5 Exhibitions and Events Beyond Words: Experimental Poetry & the Avant-Garde Drafting Monique Wittig Subscribed: The Manuscript in Britain, 1500–1800 -

ST JOHN's COLLEGE COUNCIL Agenda for the Meeting Of

ST JOHN’S COLLEGE COUNCIL Agenda For the Meeting of Wednesday, December 3, 2014 Meal at 5:30, Meeting from 6:00 in the Cross Common Room (#108) 1. Opening Prayer 2. Approval of the Agenda 3. Approval of the September 24, 2014 Minutes 4. Business arising from the Minutes 5. New Business a) Update on the work of the Commission on Theological Education b) University of Manitoba Budget situation c) Draft Report from the Theological Education Commission d) Report from Warden on the Collegiate way Conference e) Budget Summary f) Summary of Awards 6. Reports from Committees, College Officers and Student Council a) Reports from Committees – Council Executive, Development, Finance & Admin. b) Report from Assembly c) Report from College Officers and Student Council i) Warden ii) Dean of Studies iii) Development Office iv) Dean of Residence v) Chaplain vi) Bursar vii) Registrar viii) Senior Stick 7. Other Business 8. Adjournment Council Members: Art Braid; Bernie Beare; Bill Pope; Brenda Cantelo; Christopher Trott; David Ashdown; Don Phillips; Heather Richardson; Ivan Froese; Jackie Markstrom; James Ripley; Joan McConnell; June James; Justin Bouchard; Peter Brass; Sherry Peters; Simon Blaikie; Susan Close; William Regehr, Susie Fisher Stoesz, Martina Sawatzky; Diana Brydon; Esyllt Jones; James Dean; Herb Enns ST JOHN’S COLLEGE COUNCIL Minutes For the Meeting of Wednesday, September 24, 2014 Present: B. Beare (Chair), A. Braid, J. Bouchard, B. Cantelo, D Brydon, J. Ripley, P. Brass, M. Sawatzky, B. Regehr, C. Trott, S. Peters (Secretary), J. Markstrom, H. Richardson, I. Froese, J. McConnell, B. Pope. Regrets: J. James, D. Phillips, H. Enns, S. -

Selected Prizes and Awards Education Books Publication of Articles in Joel

+1 215 985 4747 ofc www.joelkatzdesign.com +1 267 242 4747 mbl www.joelkatzphotography.com [email protected] joel katz Joel Katz Design Associates 123 North Lambert St Philadelphia PA 19103 USA Selected prizes and awards The Garden Club of America Rome Prize in Landscape Architecture for a project in graphic notation, diagrammatic cartography, and photography, the American Academy in Rome, 2002–2003; Fellow of the American Academy in Rome AIGA Philadelphia Fellow, 2002 Greater Philadelphia Preservation Alliance Grand Jury Award, 2010 Honor Award in Wayfinding, Society of Environmental Graphic Designers, 2002 Kanzaki Creativity Competition, grand prize, 1992 International Pediatric Nephrology Association: Honorary Life Member, for work done for the Fifth International Pediatric Nephrology Symposium, Philadelphia PA, 1980. Strong Prize for American Literature, for Scholar of the House project, And I Said No Lord, Yale College, 1965 Education MFA and BFA in graphic design, 1967 Yale School of Art, New Haven CT BA Scholar of the House with Exceptional Distinction, 1965 Yale College, New Haven CT Aurelian Honor Society; Manuscript Society Books Joel Katz: And I Said No Lord: A 21-Year-Old in Mississippi in 1964. Tuscaloosa, University of Alabama Press, 2014. Joel Katz: Designing Information: Human Factors and Common Sense in Information Design New York, John Wiley & Sons, 2012. Included on Designers & Books/Notable Books of 2012 Alina Wheeler and Joel Katz: Brand Atlas: Branding Intelligence Made Visible. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 2011. Richard Saul Wurman, Alan Levy, and Joel Katz: The Nature of Recreation. American Federation of the Arts and GEE! Group for Environmental Education Inc., The MIT Press, 1973. -

Faculty Activities

Faculty activities left to right Bruce Ackerman Anne L. Alstott Ian Ayres Jack M. Balkin Robert Amsterdam Burt Guido Calabresi Bruce Ackerman Ian Ayres To Change) the Constitution: The Case of Lectures and Addresses Lectures and Addresses the New Departure, 39 Suffolk L. Rev. 27 Conference on a New Constitutional University of Virginia Law School, Wharton (2005); Deconstruction's Legal Career, 27 Order?, Fordham University Law School, School of Business, Georgetown Law Cardozo L. Rev. 719 (2005); Should Liberals keynote address, "The Emergency School, Stanford Law School, and Yale Law Stop Defending Roe?, Legal Affairs Debate Constitution.” School, “Market Failure and Inequality”; Club, November 28- December 2, 2005 Publications U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, “An (with S. Levinson). The Failure of the Founding Fathers: Economic Analysis of Disparity Studies”; Jefferson, Marshall and the Rise of 2006 Hart Lecture, Georgetown Law Robert Amsterdam Burt Presidential Democracy (2005); Before School, “The Secret Refund Booth”; Lectures and Addresses the Next Attack: Preserving Civil Northwestern University Department American Society of Critical Medicine, Liberties in an Age of Terrorism (2006); of Economics, “The Search for Persuasive “Law's Impact on the Quality of Dying: The Stealth Revolution Continued, London Racial Profiling Benchmarks”; University Lessons from the Schiavo Case.” Review of Books, February 9, 2006, at 18, of Arizona Conference on Economic Torts, Publications available at http://www.lrb.co.uk/v28/ “A Prestatement of Promissory Fraud”; The End of Autonomy, in Improving End of n03/acke01_.html; If Washington Blows Up, Litigato, “Straight Perspective on the Life Care: Why Has It Been So Difficult? American Prospect, March 2006, at 22; Struggle for LGBT Equality.” (B. -

1 JAY J. AGUE Curriculum Vitae Addresses: Department of Earth

JAY J. AGUE Curriculum Vitae Addresses: Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences Yale University Kline Geology Laboratory, 210 Whitney Avenue P.O. Box 208109 New Haven, CT 06520-8109 Peabody Museum of Natural History Yale University 170 Whitney Avenue P.O. Box 208118 New Haven, CT 06520-8118 Telephone: 203-432-3171 Fax: 203-432-3134 E-mail: [email protected] Web pages: http://people.earth.yale.edu/profile/jay-ague/about Education and Degrees Honorary Master of Arts Privatum, Yale University, 2004 Ph.D., University of California, Berkeley, Geology, December 1987 M.S., Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan, Geology, December 1983 B.S., Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan, Geology, May 1981 (High Distinction) Employment/Titles Chair, Yale Science and Engineering Chairs Council (2015-16) Acting Co-Director, Yale Climate and Energy Institute (2015-16) Henry Barnard Davis Memorial Professor of Geology and Geophysics (2012- ) Chair, Department of Geology and Geophysics, Yale University (1 Jul 2012-30 Jun 2018 ) Acting Director, Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History (1 Jul 2008 to 31 Dec 2008) Director of Undergraduate Studies, Geology & Geophysics, Yale University (2004-08) Professor, Department of Geology and Geophysics, Yale University (2003- ) Director of Graduate Studies, Geology & Geophysics, Yale University (Spring 2002, 2012) Curator-in-Charge of Mineralogy & Meteoritics, Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History (1998- ) Associate Professor, Department of Geology and Geophysics, Yale University (1995-2003) Director, Electron -

Biographies Speakers

Biographies Speakers Peter Salovey ’86 PhD, President of Yale University Peter Salovey is the President of Yale University where he is also a Professor of Psychology. He previously served as Yale's Provost, Dean of Graduate Studies, and Dean of Yale College. President Salovey is one of the early pioneers and leading researchers in emotional intelligence. He has authored or edited thirteen books translated into eleven languages and published more than 350 journal articles and essays, focused primarily on human emotion and health behavior. He has won numerous awards for his research and teaching. President Salovey has also served on a number of national scientific advisory boards and as officer of scientific societies in his field of research. Mark Dollhopf ‘77, Executive Director, Association of Yale Alumni Mark Dollhopf began his career on the fundraising side of alumni relations. He started working at Yale in 1977 the year of his graduation, as a staff member for the Yale Development Office – the fundraising department of Yale. In 1980, Mark co-founded the firm of Anderson, Cole & Dollhopf, and there pioneered new institutional fundraising and advancement techniques for universities and independent schools, including the first professional campus direct response programs. His firm served over 100 education, health, social service, political and religious organizations, including Yale, Brown, Columbia and Duke universities; Exeter and Andover preparatory schools; the National Wildlife Federation; the Arthritis Foundation; the Archdioceses of New York, Boston, St. Louis and Chicago; Catholic Relief Services; and Lutheran Social Services. In 1989 Anderson, Cole & Dollhopf was acquired by MCI. In 1993, Mark founded Janus Development, which counsels non-profit institutions about strategic planning, leadership and board development as well as management and marketing. -

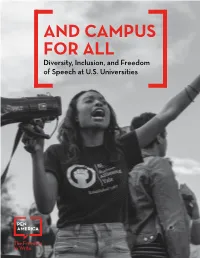

And Campus for All: Diversity, Inclusion, and Freedom of Speech at U.S. Universities

AND CAMPUS FOR ALL Diversity, Inclusion, and Freedom of Speech at U.S. Universities 1 AND CAMPUS FOR ALL Diversity, Inclusion, and Freedom of Speech at U.S. Universities October 17, 2016 © 2016 PEN America. All rights reserved. PEN America stands at the intersection of literature and human rights to protect open expression in the United States and worldwide. We champion the freedom to write, recognizing the power of the word to transform the world. Our mission is to unite writers and their allies to celebrate creative expression and defend the liberties that make it possible. Founded in 1922, PEN America is the largest of more than 100 centers of PEN International. Our strength is in our membership—a nationwide community of more than 4,000 novelists, journalists, poets, essayists, playwrights, editors, publishers, translators, agents, and other writing professionals. For more information, visit pen.org. Cover photograph: Chris Meiamed CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4 Free Speech Controversies on Campus SUMMARY 8 PEN America Principles on Campus Free Speech LEGAL FRAMEWORK 10 Free Speech at U.S. Universities A CHANGING 12 AMERICA A Changing Campus THE NEW 18 LANGUAGE OF HARM Microaggressions, Trigger Warnings, Safe Spaces ENFORCING TITLE 26 IX Sexual Harassment and Free Speech SPEECH IN 32 A STRAITJACKET Concerns for Expression on Campus MORE SPEECH, 36 BETTER SPEECH Pushing Campus Expression Forward OUTSIDE INFLUENCES 42 The New Pressures of Social Media and Evolving Educational Economics CASE STUDY 46 YALE Chilling Free Speech or Meeting Speech -

International Festival of Arts & Ideas

Festival 2012 | June 16–30 www.artidea.org New HaVeN CoNNeCtiCut - - the international Festival of arts & ideas is made possible with the support of: welcome to Festival 2012 The International Festival of Arts & Ideas is a 15-day extravaganza of performing arts and conversations— a place to tickle your senses, to engage your mind, to Official Media sponsors find inspiration, and to take off on an adventure. technology sponsor We’ve packed Festival 2012 with seriously good fun: There are speakers and conversationalists keen to share expansive ideas, and world-renowned artists Seymour L. Lustman Memorial Fund from all corners of the planet eager to share joy-filled, thought-provoking performances. ® Come play. Come see where your wits take you. Come have some SERIOUS FUN! David T. Langrock Emily Hall Tremaine Foundation Foundation table of Contents additional Media Partners MusiC, tHEATER & DanCe WYBC-AM 1340 Asphalt Orchestra FRee 6 The Ben Allison Band with Robert Pinsky 15 sPOnsORs as of 3.1.12 Eileen and Andrew Eder Roslyn Milstein Meyer and The Carolina Chocolate Drops FRee 11 Aetna Robert E. Eisele Fine Arts Trust Jerome Meyer Aldo DeDominicis Foundation, Inc. Louise Endel Judi and Dan Miglio Circa 13 New Haven Parking Authority Reverend Kevin G. Ewing Sharon and Daniel Milikowsky Erth’s Dinosaur Petting Zoo FRee 5 Pelli Clarke Pelli Richard and Barbara Feldman Michael Morand & Film Series: Paradise Regained FRee 20 Peoples United Bank Gordon and Shelley Geballe William Frank Mitchell King Lear—Contemporary Legend Theater (Taiwan) 16 Sikorsky Aircraft Corporation Sally and Stephen Glick The Howard and Maryam Newman love fail 17 Southern Connecticut Gas Company David Goldman and Family Foundation Mark Morris Dance Group 10 University of New Haven Debbie Bisno David I. -

Final Draft-New Haven

Tomorrow is Here: New Haven and the Modern Movement The New Haven Preservation Trust Report prepared by Rachel D. Carley June 2008 Funded with support from the Tomorrow is Here: New Haven and the Modern Movement Published by The New Haven Preservation Trust Copyright © State of Connecticut, 2008 Project Committee Katharine Learned, President, New Haven Preservation Trust John Herzan, Preservation Services Officer, New Haven Preservation Trust Bruce Clouette Robert Grzywacz Charlotte Hitchcock Alek Juskevice Alan Plattus Christopher Wigren Author: Rachel D. Carley Editor: Penny Welbourne Rachel D. Carley is a writer, historian, and preservation consultant based in Litchfield, Connecticut. All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. Rights to images in the collection of the New Haven Museum and Historical Society are granted for one- time use only. All photographs by Rachel Carley unless otherwise credited. Introduction Supported by a survey and planning grant from the History Division of the Connecticut Commission on Culture & Tourism, this overview of modern architecture and planning in New Haven is the first phase of a comprehensive project sponsored by the New Haven Preservation Trust. The intent is to investigate how and why the city became the center for one of the country’s most aggressive modern building programs of the post-World War II era, attracting a roster of internationally recognized architects and firms considered to be among the greatest leaders of the modernist movement. Although the architectural heritage of this city includes fine examples of early 20th- century contemporary design predating the war, the New Haven story relates most directly to the urban renewal years of the 1950s to 1970s and their dramatic reshaping of the city skyline during that period. -

Bruce Arnold Ackerman

BRUCE ARNOLD ACKERMAN Curriculum Vitae Date of Birth: August 19, 1943 Family: Married to Susan Rose-Ackerman. Children: Sybil Rose Ackerman, John Mill Ackerman. Present Position: Sterling Professor of Law and Political Science, Yale University, July 1, 1987 – Address: Yale Law School PO Box 208215 New Haven CT 06520-8215 Email: [email protected] Past Positions: 1. Law Clerk, Judge Henry J. Friendly, U.S. Court of Appeals, 1967-8 2. Law Clerk, Justice John M. Harlan, U. S. Supreme Court, 1968-9 3. Assistant Professor of Law, University of Pennsylvania Law School, 1969-71 4. Visiting Assistant Professor of Law and Senior Fellow, Yale Law School, 1971- 72 5. Associate Professor of Law & Public Policy Analysis, University of Pennsylvania, 1972-73 6. Professor of Law and Public Policy Analysis, University of Pennsylvania, 1973- 74 7. Professor of Law, Yale University, 1974-82 8. Beekman Professor of Law and Philosophy, Columbia University, 1982-87 Ackerman_CV p. 1 of 36 Education: 1. B.A. (summa cum laude), Harvard College, 1964 2. LL.B. (with honors), Yale Law School, 1967 Languages: German, Spanish, French Professional Affiliations: Member, Pennsylvania Bar; Member, American Law Institute Fields: Political philosophy, American constitutional law, comparative law and politics, taxation and welfare, environmental law, law and economics, property. Honors: Honorary Doctorate in Jurisprudence, University of Trieste, Italy, 2018; Berlin Prize, American Academy, 2015; Commander, Order of Merit of the French Republic, 2003; Henry Phillips Prize in Jurisprudence of the American Philosophical Society, 2003; Fellow, American Academy of Arts and Sciences; Fellow, Collegium Budapest, Fall 2002; Fellow, Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences, Spring 2002; Fellow, Woodrow Wilson Center, 1995-96; Fellow, Wissenschaftskolleg, Berlin 1991-92; Guggenheim Fellowship, 1985-86, Rockefeller Fellow in the Humanities, 1976-7. -

Journal of Urban History

Journal of Urban History http://juh.sagepub.com/ Planning's End? Urban Renewal in New Haven, the Yale School of Art and Architecture, and the Fall of the New Deal Spatial Order Brian Goldstein Journal of Urban History 2011 37: 400 DOI: 10.1177/0096144211400382 The online version of this article can be found at: http://juh.sagepub.com/content/37/3/400 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com On behalf of: The Urban History Association Additional services and information for Journal of Urban History can be found at: Email Alerts: http://juh.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://juh.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations: http://juh.sagepub.com/content/37/3/400.refs.html Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at Harvard Libraries on April 14, 2011 Journal of Urban History 37(3) 400 –422 Planning’s End? Urban © 2011 SAGE Publications Reprints and permission: http://www. sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Renewal in New Haven, DOI: 10.1177/0096144211400382 the Yale School of Art http://juh.sagepub.com and Architecture, and the Fall of the New Deal Spatial Order Brian Goldstein1 Abstract This article argues that the movement against urban renewal emerged not only in the streets of American cities, but also in the halls of American universities. In response to the extensive redevelopment of New Haven in the 1950s and 1960s, students at the Yale School of Art and Architecture, and especially in the Department of City Planning, marshaled an extensive critique of their expanding university’s role in this top-down reconstruction.