The Australian Greens: Between Movement and Electoral Professional Party

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Which Political Parties Are Standing up for Animals?

Which political parties are standing up for animals? Has a formal animal Supports Independent Supports end to welfare policy? Office of Animal Welfare? live export? Australian Labor Party (ALP) YES YES1 NO Coalition (Liberal Party & National Party) NO2 NO NO The Australian Greens YES YES YES Animal Justice Party (AJP) YES YES YES Australian Sex Party YES YES YES Pirate Party Australia YES YES NO3 Derryn Hinch’s Justice Party YES No policy YES Sustainable Australia YES No policy YES Australian Democrats YES No policy No policy 1Labor recently announced it would establish an Independent Office of Animal Welfare if elected, however its structure is still unclear. Benefits for animals would depend on how the policy was executed and whether the Office is independent of the Department of Agriculture in its operations and decision-making.. Nick Xenophon Team (NXT) NO No policy NO4 2The Coalition has no formal animal welfare policy, but since first publication of this table they have announced a plan to ban the sale of new cosmetics tested on animals. Australian Independents Party NO No policy No policy 3Pirate Party Australia policy is to “Enact a package of reforms to transform and improve the live exports industry”, including “Provid[ing] assistance for willing live animal exporters to shift to chilled/frozen meat exports.” Family First NO5 No policy No policy 4Nick Xenophon Team’s policy on live export is ‘It is important that strict controls are placed on live animal exports to ensure animals are treated in accordance with Australian animal welfare standards. However, our preference is to have Democratic Labour Party (DLP) NO No policy No policy Australian processing and the exporting of chilled meat.’ 5Family First’s Senator Bob Day’s position policy on ‘Animal Protection’ supports Senator Chris Back’s Federal ‘ag-gag’ Bill, which could result in fines or imprisonment for animal advocates who publish in-depth evidence of animal cruelty The WikiLeaks Party NO No policy No policy from factory farms. -

Legislative Council- PROOF Page 1

Tuesday, 15 October 2019 Legislative Council- PROOF Page 1 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL Tuesday, 15 October 2019 The PRESIDENT (The Hon. John George Ajaka) took the chair at 14:30. The PRESIDENT read the prayers and acknowledged the Gadigal clan of the Eora nation and its elders and thanked them for their custodianship of this land. Governor ADMINISTRATION OF THE GOVERNMENT The PRESIDENT: I report receipt of a message regarding the administration of the Government. Bills ABORTION LAW REFORM BILL 2019 Assent The PRESIDENT: I report receipt of message from the Governor notifying Her Excellency's assent to the bill. REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH CARE REFORM BILL 2019 Protest The PRESIDENT: I report receipt of the following communication from the Official Secretary to the Governor of New South Wales: GOVERNMENT HOUSE SYDNEY Wednesday, 2 October, 2019 The Clerk of the Parliaments Dear Mr Blunt, I write at Her Excellency's command, to acknowledge receipt of the Protest made on 26 September 2019, under Standing Order 161 of the Legislative Council, against the Bill introduced as the "Reproductive Health Care Reform Bill 2019" that was amended so as to change the title to the "Abortion Law Reform Bill 2019'" by the following honourable members of the Legislative Council, namely: The Hon. Rodney Roberts, MLC The Hon. Mark Banasiak, MLC The Hon. Louis Amato, MLC The Hon. Courtney Houssos, MLC The Hon. Gregory Donnelly, MLC The Hon. Reverend Frederick Nile, MLC The Hon. Shaoquett Moselmane, MLC The Hon. Robert Borsak, MLC The Hon. Matthew Mason-Cox, MLC The Hon. Mark Latham, MLC I advise that Her Excellency the Governor notes the protest by the honourable members. -

Independents in Federal Parliament: a New Challenge Or a Passing Phase?

Independents in Federal Parliament: A new challenge or a passing phase? Jennifer Curtin1 Politics Program, School of Political and Social Inquiry Monash University, Melbourne, Australia. [email protected] “Politics just is the game played out by rival parties, and anyone who tries to play politics in some way entirely independent of parties consigns herself to irrelevance.” (Brennan, 1996: xv). The total dominance of Australia’s rival parties has altered since Brennan made this statement. By the time of the 2001 federal election, 29 registered political parties contested seats and while only the three traditional parties secured representation in the House of Representatives (Liberals, Nationals and Labor) three independents were also elected. So could we argue that the “game” has changed? While it is true that government in Australia, both federally and in the states and territories, almost always alternates between the Labor Party and the Liberal Party (the latter more often than not in coalition with the National Party), independent members have been a feature of the parliaments for many years, particularly at the state level (Costar and Curtin, 2004; Moon,1995). Over the last decade or so independents have often been key political players: for a time, they have held the balance of power in New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, South Australia, Tasmania and the Australian Capital Territory. More generally, since 1980 an unprecedented 56 independents have served in Australian parliaments. In 2003, 25 of them were still there. This is more than six times the number of independents elected in the 1970s. New South Wales has been the most productive jurisdiction during that time, with fourteen independent members, and Tasmania the least, with only one. -

23. Explaining the Results

23. Explaining the Results Antony Green Labor came to office in 2007 with its strongest hold on government in the nation’s history—it was, for the first time, in office nationally and in every state and territory. Six years later Labor left national office with its lowest first preference vote in a century. For only the third time since the First World War, a governing party failed to win a third term in office. From a clean sweep of governments in 2007, by mid-2014 Labor’s last bastions were minority governments in South Australia and the Australian Capital Territory.1 Based on the national two-party-preferred vote, Labor’s 2013 result was less disastrous than previous post-war lows in 1966, 1975, 1977 and 1996. Labor also bettered those four elections on the proportion of House seats won. The two-party-preferred swing of 3.6 percentage points was also small for a change of government election, equal to the swing that defeated the Fraser Government in 1983 but smaller than those suffered by Whitlam in 1975, Keating in 1996 and Howard in 2007. Even over two elections from 2007 to 2013, the two-party- preferred swing of 6.2 percentage points was below that suffered by Labor previously over two elections (1961–66 and 1972–75), and smaller than the swing against the Coalition between 1977 and 1983. By the measure of first preference vote share, the 2013 election was a dreadful result for Labor, its lowest vote share since 1904.2 Labor’s vote share slid from 43.4 per cent in 2007 to 38.0 per cent in 2010 and 33.4 per cent in 2013. -

The Australian Democrats Andrew Bartlett*

Australian Cultural History Vol. 27, No.2, October 2009, 187-193 The Australian Democrats Andrew Bartlett* The Australian Democrats had maintained a presence in the Senate since 1977, but the 2007 election threatened to end their representation for good. Their efforts to retain seats proved to be in vain. Keywords: 2007 election; Australian Democrats; Senate Following on from the 2004 election, where the Australian Democrats lost four seats (including the Democrat seat Meg Lees had taken with her when she resigned from the party in 2002), plus official parliamentary status and balance of power in the Senate, the Party faced a very difficult task in the 2007 election trying to keep its four remaining Senate seats. Right throughout John Howard's fourth term, opinion polls showed public support for the Democrats consistently scraping along rock bottom levels of 1 or 2 per cent, as they had ever since the Lees resignation and the related public implosion of Natasha Stott Despoja's leadership in 2002. Even though the removal of the Democrats from the balance of power after the 2004 poll led directly to the Coalition government gaining control of the Senate, where it frequently used its majority to stifle scrutiny and bulldoze through some controversial legislation, the Democrats were unable to use this situation to build public support for returning the Party to its traditional Senate watchdog position. The Party had avoided going into debt in its 2004 campaign, so there were sufficient funds to run a basic campaign in priority areas for the 2007 election. However, serious use of paid advertising was not feasible. -

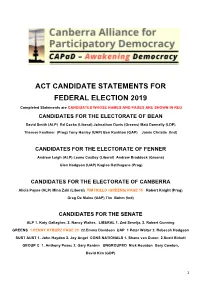

File of Candidate Statements 1

ACTwww.canberra CANDIDATE STATEMENTS-alliance.org.au FOR FEDERAL ELECTION 2019 Completed Statements are CANDIDATES WHOSE NAMES AND PAGES ARE SHOWN IN RED Responses to CANDIDATES FOR THE ELECTORATE OF BEAN [email protected] David Smith (ALP) Ed Cocks (Liberal) Johnathan Davis (Greens) Matt Donnelly (LDP) Enquiries to Bob Douglas Therese Faulkner (Prog) Tony Hanley (UAP) Ben Rushton (GAP) Jamie Christie (Ind)Tel 02 6253 4409 or 0409 233138 CANDIDATES FOR THE ELECTORATE OF FENNER Dear Dr Christie, Andrew Leigh (ALP) Leane Castley (Liberal) Andrew Braddock (Greens) Glen Hodgson (UAP) Kagiso Ratlhagane (Prog) I understand you are a candidate for the forthcoming Federal Election. CANDIDATES FOR THE ELECTORATE OF CANBERRA Congratulations, and best wishes.Alicia Payne (ALP) Mina Zaki (Liberal) TIM HOLLO (GREENS) PAGE 15 Robert Knight (Prog) Greg De Maine (UAP) Tim Bohm (Ind) I am writing on behalf of The Canberra Alliance for Participatory Democracy (CAPaD), which was formed in 2014, because many CanberransCANDIDATES were FORconcerned THE SENATE at the directions that Australian democracy was taking. ALP 1. Katy Gallagher, 2. Nancy Waites. LIBERAL 1. Zed Seselja, 2. Robert Gunning GREENS 1.PENNY KYBURZ PAGE 23 22.Emma Davidson UAP 1 Peter Walter 2. Rebecah Hodgson CAPaD seeks to enhanceSUST democracy AUST 1. John Haydon 2. Joyin Angel Canberra, CONS NATIONALS 1. Shaneso van Durenthat 2.Scott citizensBirkett can trust their elected GEOUP C 1. Anthony Pesec 2. Gary Kentnn UNGROUPED Nick Houston Gary Cowton, representatives, hold them accountable, engageDavid Kim in (GDP) decision -making, and defend what sustains the public interest. In the lead up to the 2016 ACT Legislative Assembly Elections, the major1 parties were consulted for their views about individual candidate statements, and in the light of those responses, a candidate statement was prepared, which we offered to all registered candidates for lodgement on the CAPaD website. -

Ambassade De France En Australie – Service De Presse Et Information Site : Tél

Online Press review 7 May 2015 The articles in purple are not available online. Please contact the Press and Information Department. FRONT PAGE New Greens leaders seek ‘common ground’ on reform (AUS) Crowe The Greens are promising a fresh look at major budget savings after the sudden installation of Richard Di Natale as the party’s new leader signalled a dramatic shift in power to a new generation but stirred internal rancour. Get over historical indigenous wrongs: Noel Pearson (AUS) Bita Aboriginal leader Noel Pearson has challenged indigenous Australians to get over their traumatic history in the same way that Jews survived the Holocaust. Federal budget 2015: GST on Netflix and more on the way (CAN+SMH) Martin The federal government will move to impose the goods and services tax on services such as Netflix under new rules set to be included in next week's budget. Federal budget 2015: Census saved, $250m investment in Bureau of Statistics (CAN) Martin The census has been saved and the Australian Bureau of Statistics will get a $250 million funding boost as part of the biggest technology upgrade in its 110-year history. DOMESTIC AFFAIRS POLITICS Abbott rejects slur on Paris meeting as Fairfax Media slammed (AUS) Owens Tony Abbott has denied knowing that ambassador Stephen Brady’s male partner had been instructed to leave the tarmac of a Paris airport before the Prime Minister’s arrival on Anzac Day. Smearing Tony Abbott as a homophobe is victory for hatred (AUS/Comment) Kenny Given Tony Abbott has been dubbed a misogynist, Islamophobe and racist, I suppose the - occasional allegation of homophobia shouldn’t be a surprise. -

Balance of Power Senate Projections, Spring 2018

Balance of power Senate projections, Spring 2018 The Australia Institute conducts a quarterly poll of Senate voting intention. Our analysis shows that major parties should expect the crossbench to remain large and diverse for the foreseeable future. Senate projections series, no. 2 Bill Browne November 2018 ABOUT THE AUSTRALIA INSTITUTE The Australia Institute is an independent public policy think tank based in Canberra. It is funded by donations from philanthropic trusts and individuals and commissioned research. We barrack for ideas, not political parties or candidates. Since its launch in 1994, the Institute has carried out highly influential research on a broad range of economic, social and environmental issues. OUR PHILOSOPHY As we begin the 21st century, new dilemmas confront our society and our planet. Unprecedented levels of consumption co-exist with extreme poverty. Through new technology we are more connected than we have ever been, yet civic engagement is declining. Environmental neglect continues despite heightened ecological awareness. A better balance is urgently needed. The Australia Institute’s directors, staff and supporters represent a broad range of views and priorities. What unites us is a belief that through a combination of research and creativity we can promote new solutions and ways of thinking. OUR PURPOSE – ‘RESEARCH THAT MATTERS’ The Institute publishes research that contributes to a more just, sustainable and peaceful society. Our goal is to gather, interpret and communicate evidence in order to both diagnose the problems we face and propose new solutions to tackle them. The Institute is wholly independent and not affiliated with any other organisation. Donations to its Research Fund are tax deductible for the donor. -

Introduction to Volume 1 the Senators, the Senate and Australia, 1901–1929 by Harry Evans, Clerk of the Senate 1988–2009

Introduction to volume 1 The Senators, the Senate and Australia, 1901–1929 By Harry Evans, Clerk of the Senate 1988–2009 Biography may or may not be the key to history, but the biographies of those who served in institutions of government can throw great light on the workings of those institutions. These biographies of Australia’s senators are offered not only because they deal with interesting people, but because they inform an assessment of the Senate as an institution. They also provide insights into the history and identity of Australia. This first volume contains the biographies of senators who completed their service in the Senate in the period 1901 to 1929. This cut-off point involves some inconveniences, one being that it excludes senators who served in that period but who completed their service later. One such senator, George Pearce of Western Australia, was prominent and influential in the period covered but continued to be prominent and influential afterwards, and he is conspicuous by his absence from this volume. A cut-off has to be set, however, and the one chosen has considerable countervailing advantages. The period selected includes the formative years of the Senate, with the addition of a period of its operation as a going concern. The historian would readily see it as a rational first era to select. The historian would also see the era selected as falling naturally into three sub-eras, approximately corresponding to the first three decades of the twentieth century. The first of those decades would probably be called by our historian, in search of a neatly summarising title, The Founders’ Senate, 1901–1910. -

Bicameralism in the New Zealand Context

377 Bicameralism in the New Zealand context Andrew Stockley* In 1985, the newly elected Labour Government issued a White Paper proposing a Bill of Rights for New Zealand. One of the arguments in favour of the proposal is that New Zealand has only a one chamber Parliament and as a consequence there is less control over the executive than is desirable. The upper house, the Legislative Council, was abolished in 1951 and, despite various enquiries, has never been replaced. In this article, the writer calls for a reappraisal of the need for a second chamber. He argues that a second chamber could be one means among others of limiting the power of government. It is essential that a second chamber be independent, self-confident and sufficiently free of party politics. I. AN INTRODUCTION TO BICAMERALISM In 1950, the New Zealand Parliament, in the manner and form it was then constituted, altered its own composition. The legislative branch of government in New Zealand had hitherto been bicameral in nature, consisting of an upper chamber, the Legislative Council, and a lower chamber, the House of Representatives.*1 Some ninety-eight years after its inception2 however, the New Zealand legislature became unicameral. The Legislative Council Abolition Act 1950, passed by both chambers, did as its name implied, and abolished the Legislative Council as on 1 January 1951. What was perhaps most remarkable about this transformation from bicameral to unicameral government was the almost casual manner in which it occurred. The abolition bill was carried on a voice vote in the House of Representatives; very little excitement or concern was caused among the populace at large; and government as a whole seemed to continue quite normally. -

2019 Nsw State Budget Estimates – Relevant Committee Members

2019 NSW STATE BUDGET ESTIMATES – RELEVANT COMMITTEE MEMBERS There are seven “portfolio” committees who run the budget estimate questioning process. These committees correspond to various specific Ministries and portfolio areas, so there may be a range of Ministers, Secretaries, Deputy Secretaries and senior public servants from several Departments and Authorities who will appear before each committee. The different parties divide up responsibility for portfolio areas in different ways, so some minor party MPs sit on several committees, and the major parties may have MPs with titles that don’t correspond exactly. We have omitted the names of the Liberal and National members of these committees, as the Alliance is seeking to work with the Opposition and cross bench (non-government) MPs for Budget Estimates. Government MPs are less likely to ask questions that have embarrassing answers. Victor Dominello [Lib, Ryde], Minister for Customer Services (!) is the minister responsible for Liquor and Gaming. Kevin Anderson [Nat, Tamworth], Minister for Better Regulation, which is located in the super- ministry group of Customer Services, is responsible for Racing. Sophie Cotsis [ALP, Canterbury] is the Shadow for Better Public Services, including Gambling, Julia Finn [ALP, Granville] is the Shadow for Consumer Protection including Racing (!). Portfolio Committee no. 6 is the relevant committee. Additional information is listed beside each MP. Bear in mind, depending on the sitting timetable (committees will be working in parallel), some MPs will substitute in for each other – an MP who is not on the standing committee but who may have a great deal of knowledge might take over questioning for a session. -

The Inside Line

MRA ACT Newsletter August 2012 The Inside Line EXECUTIVE President’s Report I attended the ACT Government Motorcycle Users Group (MUG) last week PRESIDENT as did Peter Major. It was a good meeting with a complete roll up of Jennifer Woods delegates from Roads ACT, ACT Police, Industry representative, NRMA Road [email protected] User Services, and Stay Upright. 0418 215 336 Discussions evolved around standardisation with the other states and territories of the LAMS bikes – maximum of 660cc. This is under discussion Snr VICE PRESIDENT currently. MRA ACT will write to express our views. Confusion is currently Kathleen Parsons caused with cross jurisdiction travel as well as the transient nature of many [email protected] Canberra residents. Helmets – dissatisfaction all around as riders do not understand what is VICE PRESIDENT legal, the retailers can be liable for selling a non-compliant helmet but Major Events Coordinator struggle without clear guidelines, and the Police find it difficult to easily Trish Holdsworth differentiate between a compliant and non-compliant helmet. The helmet [email protected] issue was a continuation of the discussion from the previous MUG meeting. The treatment for registration label / no rego label is still unclear with no SECRETARY decision from ACT Government yet. Public Officer The MRA ACT introduced and expressed support for limited use of cycle Nicky Hussey lanes for other two wheel track vehicles, allowing filtering and the [email protected] introduction of filter boxes at lights. Needless to say, this generated discussion but it will be an ongoing campaign. TREASURER Demerit points for traffic offences are now transferring between states Membership Secretary and territories so do be aware of that.