Towards the Cap Health Check and the European Budget Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Austria and Europe: Past Success and Future Perspective

SPEECH/05/119 José Manuel BARROSO President of the European Commission Austria and Europe: past success and future perspective 10th anniversary of Austria’s accession to the EU Vienna, 25 February 2005 Dear Chancellor Schüssel, Dear Foreign Minister Plassnik, Dear Chancellor Vranitzky, Dear President Lipponen, Dear Chancellor Kohl, Dear President Sigmund, Dear Commissioner Ferrero-Waldner, Excellencies, Ladies and Gentlemen, And, may I say, dear friends, 1) I am delighted to be here with you today: On a day which celebrates a historical decision for Austria and for Europe; At a time when Europe is facing major challenges which call for a European renewal. 2) The celebration of historical landmarks sometimes carries the risk of complacency: the risk of looking back at what has been achieved, and of sitting back self-satisfied about the past record. This ignores the fact that nothing we have achieved can be taken for granted. As Oliver Wendell Holmes reminds us, “the great thing in this world is not so much where we stand, as in what direction we are moving - we must sail sometimes with the wind and sometimes against it - but we must sail, and not drift, nor lie at anchor”. 3) I therefore welcome Austria’s decision to have a “Jubiläumsjahr” and to see it as a year of reflection on the past and on the future rather than as a simple year of remembrance. By taking stock of the past, we should consider our future. This is why I will not limit my speech to celebrate the past 10 years of Austria’s membership in the EU, but also look at what he have to face in the years to come. -

A Fischler Reform of the Common Agricultural Policy? Johan F.M

CENTRE FOR W ORKING D OCUMENT N O . 173 EUROPEAN S EPTEMBER 2001 POLICY STUDIES A FISCHLER REFORM OF THE COMMON AGRICULTURAL POLICY? JOHAN F.M. SWINNEN 1. Introduction 1 2. A (Very) Brief History of the CAP and Agenda 2000 3 2.1 The CAP 3 2.2 Agenda 2000 4 2.3 Did Agenda 2000 go far enough 5 3. The Pressures for Further CAP Reform 6 3.1 WTO 6 3.1.1 Export subsidies 9 3.1.2 Domestic support 10 3.2 Other trade negotiations 13 3.3 Eastern Enlargement 14 3.3.1 Enlargement and WTO 15 3.3.2 Production and Trade Effects 16 3.4 Food Safety 19 4. Reform + Reform = More or Less Reform 20 5. The Future of the Direct Payments 22 6. Direct Payments and Enlargement 23 6.1 Direct Payments for CEEC Farmers 23 6.2 Budgetary Implications 25 7. Budget Pressures and CAP Reform 27 8. Direct Payments and WTO 29 9. Timing 30 10. The Pro- and Anti-Reform Coalitions 33 10.1 Enlargement and Reform Coalitions 36 11. Lessons from the History of CAP Reforms 37 12. A Hint of the 2004 Fischler Reforms ? 39 References 43 Tables and Figures 46 CEPS Working Documents are published to give an early indication of the work in progress within CEPS research programmes and to stimulate reactions from other experts in the field. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed are attributable only to the author in a personal capacity and not to any institution with which he is associated. -

Portfolio Responsibilities of the Barroso Commission

IP/04/1030 Brussels, 12 August 2004 Portfolio Responsibilities of the Barroso Commission Responsibilities Departments1 José Manuel BARROSO President Responsible for: - Political guidance of the Commission - Secretariat General - Organisation of the Commission in - Legal Service order to ensure that it acts - Spokesperson consistently, efficiently and on the - Group of Policy Advisers (GOPA) basis of collegiality - Allocation of responsibilities Chair of Group of Commissioners on Lisbon Strategy Chair of Group of Commissioners for External Relations Margot WALLSTRÖM Vice President Commissioner for Institutional Relations and Communication Strategy Press and Communication DG including Responsible for: Representations in the Member States - Relations with the European Parliament - Relations with the Council and representation of the Commission, under the authority of the President, in the General Affairs Council - Contacts with National Parliaments - Relations with the Committee of the Regions, the Economic and Social Committee, and the Ombudsman - Replacing the President when absent - Coordination of press and communication strategy Chair of Group of Commissioners for Communications and Programming 1 This list of department responsibilities is indicative and may be subject to adjustments at a later stage Günter VERHEUGEN Vice President Commissioner for Enterprise and Industry Responsible for: - DG Enterprise and Industry - Enterprise and industry (renamed), adding: - Coordination of Commission’s role in - Space (from DG RTD) the Competitiveness -

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, C(2010) 3652 Final REPORT

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, C(2010) 3652 final REPORT FINANCIAL REPORT ECSC in Liquidation at 31 December 2009 EN EN EN FINANCIAL REPORT ECSC in Liquidation at 31 December 2009 Contents page Activity report 5 Expiry of the ECSC Treaty and the management mandate given to the European Commission 6 Winding-up of the ECSC financial operations in progress on expiry of the ECSC Treaty 7 Management of assets 12 Financing of coal and steel research 13 Financial statements of the ECSC in liquidation 14 Independent Auditor’s report on the financial statements 15 Balance sheet at 31 December 2009 17 Income statement for the year ended 31 December 2009 18 Statement of changes in equity for the year ended 31 December 2009 19 Cash flow statement for the year ended 31 December 2009 20 Notes to the financial statements at 31 December 2009 21 A. General information 21 B. Summary of significant accounting policies 22 C. Financial Risk Management 27 D. Explanatory notes to the balance sheet 36 E. Explanatory notes to the income statement 47 F. Explanatory notes to the cash flow statement 52 G. Off balance sheet 53 H. Related party disclosures 53 I. Events after the balance sheet date 53 EN 2 EN ECSC liquidation The European Coal and Steel Community was established under the Treaty signed in Paris on 18 April 1951. The Treaty entered into force in 1952 for a period of fifty years and expired on 23 July 2002. Protocol (n°37) on the financial consequences of the expiry of the ECSC Treaty and on the creation and management of the Research Fund for Coal and Steel is annexed to the Treaty on the functioning of the European Union. -

List of College of Europe Alumni Holding High Positions

LIST OF COLLEGE OF EUROPE ALUMNI HOLDING HIGH POSITIONS SURNAME Given name Promotion Citizenship Function ACCILI - SABBATINI Maria 1979-1980 (IT) Ambassador of Italy to Hungary (Budapest) (since 30.05.2012) Assunta ADINOLFI Gaetano 1950-1951 (IT) President of the European Cinema Support Fund “EURIMAGES” (Council of Europe), (retired) Deputy Secretary General of the Council of Europe (1978 – 1993), elected by the Parliamentary Assembly for a period of five years, then twice re-elected. AGUIAR MACHADO João 1983-1984 (PT) - Director General DG MARE (September 2015 - present) – European Luis, PAVÃO de Commission - Director-General DG "Mobility and Transport" (MOVE) (May 2014 - August 2015) – European Commission - Deputy Director-General, for services, investment, intellectual property, government procurement, bilateral trade relations with Asia, Africa and Latin America, DG TRADE (January 2009 - April 2014) – European Commission - Deputy Director-General in charge of Asia and Latin America, DG EXTERNAL RELATIONS (September 2007 - December 2008) – European Commission - Director, for trade in services and investment, bilateral trade relations with the Americas and the Far East, DG TRADE (January 2007 - September 2007) – European Commission Dijver 11 · 8000 Brugge · Belgium/Belgique T +32 50 47 71 11 · F +32 50 47 71 10 · [email protected] - Director, for trade in services and investment; agriculture, SPS; sustainable development. Bilateral trade relations with China, DG TRADE (April 2004 - December 2006) - European Commission - Head of Unit, -

Top Margin 1

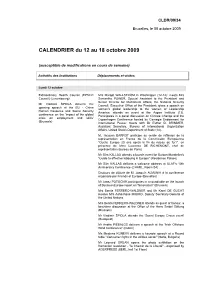

CLDR/09/34 Bruxelles, le 08 octobre 2009 CALENDRIER du 12 au 18 octobre 2009 (susceptible de modifications en cours de semaine) Activités des Institutions Déplacements et visites Lundi 12 octobre Extraordinary Health Council (EPSCO Mrs Margot WALLSTRÖM in Washington (12-14): meets Mrs Council) (Luxembourg) Samantha POWER, Special Assistant to the President and Senior Director for Multilateral Affairs, the National Security Mr Vladimír ŠPIDLA delivers the Council, Executive Office of the President; gives a speech on opening speech at the EU - China women's global leadership to the women of Leadership Human Resource and Social Security America; attends an event at the Aspen Institute (13). conference on the 'impact of the global Participates in a panel discussion on Climate Change and the crisis on employment and skills' Copenhagen Conference hosted by Carnegie Endowment for (Brussels) International Peace; meets with Dr Esther D. BRIMMER, Assistant Secretary, Bureau of International Organization Affairs, United States Department of State (14). M. Jacques BARROT participe au cercle de réflexion de la représentation en France de la Commission Européenne "Quelle Europe 20 ans après la fin du rideau de fer?", en présence de Mme Laurence DE RICHEMONT, chef de représentation (bureau de Paris) Mr Siim KALLAS attends a launch event for Burson-Marsteller's "Guide to effective lobbying in Europe" (Residence Palace) Mr Siim KALLAS delivers a welcome address at OLAF's 10th Anniversary Conference (CHARL, Room S4) Discours de clôture de M. Joaquín ALMUNIA -

Politics: the Right Or the Wrong Sort of Medicine for the EU?

Policy paper N°19 Politics: The Right or the Wrong Sort of Medicine for the EU? Two papers by Simon Hix and Stefano Bartolini Notre Europe Notre Europe is an independent research and policy unit whose objective is the study of Europe – its history and civilisations, integration process and future prospects. The association was founded by Jacques Delors in the autumn of 1996 and presided by Tommaso Padoa- Schioppa since November 2005. It has a small team of in-house researchers from various countries. Notre Europe participates in public debate in two ways. First, publishing internal research papers and second, collaborating with outside researchers and academics to contribute to the debate on European issues. These documents are made available to a limited number of decision-makers, politicians, socio-economists, academics and diplomats in the various EU Member States, but are systematically put on our website. The association also organises meetings, conferences and seminars in association with other institutions or partners. Proceedings are written in order to disseminate the main arguments raised during the event. Foreword With the two papers published in this issue of the series “Policy Papers”, Notre Europe enters one of the critical debates characterising the present phase of the European construction. The debate revolves around the word ‘politicisation’, just as others revolve around words like ‘democracy’, ‘identity’, bureaucracy’, ‘demos’, ‘social’. The fact that the key words of the political vocabulary are gradually poured into the EU mould is in itself significant. In narrow terms, the issue at stake is whether the European institutions should become ‘politicised’ in the sense in which national institutions are, i.e. -

Globalising Hunger: Food Security and the EU's Common Agricultural

Globalising Hunger Food Security and the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) Author: Thomas Fritz 1 DRAFT Globalising Hunger: Food Security and the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) Author: Thomas Fritz 1 This is still a draft version. On October 12 the Commission’s legislative proposals for the new CAP will be presented. The final version of this study will integrate these proposals in order to be useful into the next year when the EP and the Council have their discussions on the CAP. Contents 1 INTRODUCTION 4 4.3 Opening the flood gates: EU milk exports 48 Swamping African markets 53 2 GOING GLOBAL: Milk powder in Cameroon 56 EUROPEAN AGRI-FOOD INDUSTRY 7 Free trade and the fight against import surges 60 4.4 Europe plucks Africa: EU poultry exports 65 3 CAP: WINNERS AND LOSERS IN EUROPE 13 Risking public health 70 Import restrictions and loopholes 71 3.1 A never-ending story: CAP reforms 15 4.5 Feeding factory farms: EU soy imports 74 3.2 The decoupling fraud 21 The EU as a land grabber 81 3.3 Unequal distribution of funds 24 A toxic production model 85 3.4 The losers: Small farms 30 5 RECOMMENDATIONS 88 4 CAP IMPACTS IN THE GLOBAL SOUTH 32 4.1 Import dependency and food deficit 32 4.2 Colonising food: EU cereal exports 37 Changing eating habits: Wheat flour in Kenya 40 Cereal price shock in West Africa 43 EPAs: Securing export markets 46 Globalising Hunger: Food Security and the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) 1 Introduction erous CAP subsidies awarded to European farmers and food processors. -

Euro-Compatible” Towards 50 Bn Euro Additional Funding for Class Actions Low Carbon Technologies by Dafydd Ab Iago Credible Technology Road Maps

ENERGY EFFICIENCY LISBON TREATY EU/SOUTH KOREA Mobilising ICT for low carbon Jan Fischer: Prague will ratify Commission backs initialling economy Page 9 by end of year Page 14 of FTA on 15 October Page 15 EUROPOLITICS The European affairs daily Thursday 8 October 2009 N° 3834 37th year FOCUS ENERGY “Euro-compatible” Towards 50 bn euro additional funding for class actions low carbon technologies By Dafydd ab Iago credible technology road maps. That took The French consumer associations CLCV more time.” and UFC Que-Choisir have sent a letter The European Commission adopted, to the European Commission signed by on 7 October, a communication calling WHERE THE BULK IS 33,000 people calling for the possibil- for an additional investment of €50 billion The Commission’s analysis, given in the ity of bringing class actions “as soon in energy technology research over the staff working document, indicates large as possible,” it announces in a press next ten years1. The additional funding - if gaps with other sectors. Research Com- release dated 7 October. The associa- plans are eventually endorsed by member missioner Janez Potocnik noted that a tions have been waiting since 2005 for states - would result in almost tripling cur- relatively low rate of investment in R&D promises by the public authorities to rent annual spending of some €3 billion, to in the renewable energy sector of only 3% introduce the concept of class actions in €8 billion2. Aside from public authorities, compares to higher rates in other sectors, France to materialise. The move is being the Commission’s call for more money is such as IT, at 8%. -

Fischler Reform

GJAE 59 (2010), Supplement Perspectives on International Agricultural Policy – In Honor of the Retirement of Professor Stefan Tangermann The Political Economy of the Most Radical Reform of the Common Agricultural Policy Die politische Ökonomie der bisher umfassendsten Reform der Gemeinsamen Agrarpolitik der EU Jo Swinnen Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Belgium Abstract ference. It has long been considered by foes, rightly or wrongly, as a policy impossible to reform substantial- The 2003 reform of the European Union’s Common ly because of the staunch opposition to reform from Agricultural Policy (CAP) under Commissioner powerful farm and agribusiness lobbies and also be- Fischler was the most radical in the history of the cause of the complications of European politics. CAP. This paper analyzes the causes and constraints In 1995 Franz Fischler, a then largely unknown of the 2003 reform. The paper argues that an unusual Austrian politician, became EU Commissioner in combination of pro-reform factors such as institution- charge of the CAP. This was a surprise because a new al reforms, changes in the number and quality of the member state had been given the powerful Agricultur- political actors involved in the reform process, and al Commission chair. Although there were no major strong calls to reform from external factors came expectations with his arrival in Brussels, a decade together in the first few years of the 21st century, al- (two tenures) later, Fischler was recognized by friend lowing this reform to be possible. and foe to be the architect of the most radical reforms Key words to the CAP. This paper is the first in the literature which at- Common Agricultural Policy; 2003 Reform; Mid Term tempts to answer the question: what made the radical Review; Political Economy; Fischler Reform reforms, and in particular the 2003 reform, of the CAP possible? The paper analyzes how various factors Zusammenfassung contributed to this political outcome. -

The Schüssel Era in Austria Günter Bischof, Fritz Plasser (Eds.)

The Schüssel Era in Austria Günter Bischof, Fritz Plasser (Eds.) CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIAN STUDIES Volume 18 innsbruck university press Copyright ©2010 by University of New Orleans Press, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to UNO Press, University of New Orleans, ED 210, 2000 Lakeshore Drive, New Orleans, LA, 70119, USA. www.unopress.org. Printed in the United States of America. Published and distributed in the United States by Published and distributed in Europe by University of New Orleans Press: Innsbruck University Press: ISBN 978-1-60801-009-7 ISBN 978-3-902719-29-4 Library of Congress Control Number: 2009936824 Contemporary Austrian Studies Sponsored by the University of New Orleans and Universität Innsbruck Editors Günter Bischof, CenterAustria, University of New Orleans Fritz Plasser, Universität Innsbruck Production Editor Copy Editor Assistant Editor Ellen Palli Jennifer Shimek Michael Maier Universität Innsbruck Loyola University, New Orleans UNO/Vienna Executive Editors Franz Mathis, Universität Innsbruck Susan Krantz, University of New Orleans Advisory Board Siegfried Beer Sándor Kurtán Universität Graz Corvinus University Budapest Peter Berger Günther Pallaver Wirtschaftsuniversität -

Top Margin 1

CLDR/09/18 Bruxelles, le 15 mai 2009 CALENDRIER du 18 au 31 mai 2009 (susceptible de modifications en cours de semaine) Activités des Institutions Déplacements et visites Lundi 18 mai Conseil "Affaires générales et relations Mrs Margot WALLSTRÖM receives Mr Murray MCCULLY, extérieures" (CAGRE) (18-19) Minister of Foreign Affairs of New Zealand Réunion du Conseil d'association UE - Mr Jacques BARROT receives Mr Vygaudas UŠACKAS, Israël (18-19) Lithuanian Minister of Foreign Affairs Réunion du Conseil de stabilisation et Mr Joe BORG addresses the Seychelles Forum (Mahe Island, d'association UE – Albanie Seychelles) EU - New Zealand Ministerial Troika Mr Janez POTOČNIK receives Mr Diego LÓPEZ GARRIDO, Spanish State Secretary for European Affairs Mr Ján FIGEL' in Brazil (17-20): meets Mr Joao SILVA FERREIRA, Brazilian Minister of Culture and Signature of Joint Declaration on Culture; meets Mr Fernando HADDAD, Brazilian Minister of Education and Signature of Joint Declaration; gives a courtesy call to Minister Luiz Soares DULCI, Secretary General of the Presidency in charge of Youth ; meets Mr Y. David WEITMAN, Member of the Board and Founder of Ten Yad Beit Yaacov School; meets Mr Carlos Alberto VOGT, Secretary of Higher Education and Presidents of the State Universities UNESP, UNICAMP and USP; meets Mr Joao SAYAD, Secretary of Culture of the Government of the State of Sao Paulo; visits the Pinacoteca Museum from Sao Paulo Mr Olli REHN meets Mrs Tarja HALONEN, President of the Republic of Finland (Mäntyniemi, Finland) Mrs Mariann FISCHER BOEL in China (18-22): launch of "Tasty Europe" promotional week (18, Shanghai). Inauguration of the 10th SIAL Food & Beverage trade show (19, Shanghai).